Steve McQueen was in the middle of his career's big hot streak when he made Nevada Smith in 1966, between The Cincinnati Kid and The Sand Pebbles. He had the momentum of The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape behind him, and The Thomas Crown Affair and Bullitt in the near future. In retrospect, things would probably never be better for the actor, and though it wouldn't be until 1974 that he officially became the highest paid actor in the world, that pyrrhic honour would ultimately (and inevitably) be the beginning of the end.

Like so many of his roles, he was reluctant about the picture (he'd recently passed on King Rat), but his then-wife Neile took him aside after the story was pitched by his agents Stan Kamen and Abe Lastfogel and said, "Take it." The film he really wanted to make was a racing picture called Day of the Champion, which he would ultimately make as Le Mans, perhaps to his regret. But more about that another time.

The film was a prequel, its whole story carved out of an anecdote about a character played by Alan Ladd in Edward Dmytryk's 1964 movie version of The Carpetbaggers, the best-selling Harold Robbins novel, which was itself sloppily based on the life of Howard Hughes. The Dmytryk film was suitably overwrought and salacious and was a massive hit. Today both book and movie are remembered as milestones of the budding sexual revolution, though Robbins is a period footnote, and the film nearly impossible to see.

In his 2001 biography of McQueen, Christopher Sandford calls Nevada Smith a "horse opera," and he's not wrong. Both contemporary and backward-looking, it was the sort of straight-up western being made less and less in Hollywood, where the current fashion was for spoofs like Cat Ballou, released the previous year and nominated for five Oscars. (Lee Marvin would win best actor, with a role few of his fans cherish.)

When we meet McQueen his character is named Max Sand, and he's the son of a white prospector and a Kiowa woman, a "boy" who neither reads nor writes, drinks or gambles. Perhaps that's why he naively directs three strangers looking for his father to their home, before they scare his horse away as they ride full tilt to the house.

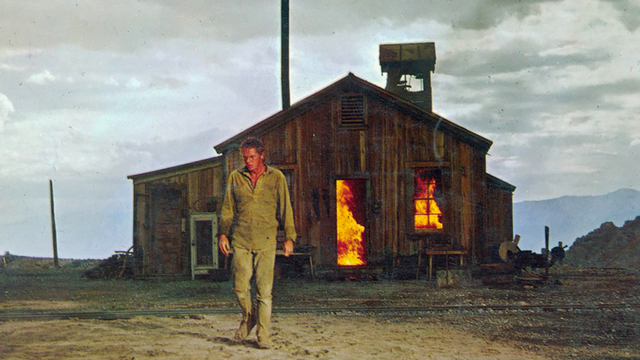

The three strangers – played by Karl Malden, Martin Landau and Arthur Kennedy – are very bad men, and by the time Max finally makes it home they've tortured and killed his parents. The boy rejects the offer of a new place to live with kind neighbours, turns the house into a funeral pyre and swears revenge on the men.

Nevada Smith is a story about a journey, appropriately helmed by Henry Hathaway, the epitome of the Hollywood journeyman director. Hathaway began his career as an assistant on silent epics like The Ten Commandments (1923) and Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925) before a series of westerns with Randolph Scott led to two films with Gary Cooper – The Lives of a Bengal Lancer and Peter Ibbetson, both released in 1935 – that would establish him as a name director at Paramount and Fox.

He'd make a series of very good film noirs at Fox in the second half of the forties – titles like The House on 92nd Street (1945), The Dark Corner (1946), 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) and Call Northside 777 (1948) before directing Marilyn Monroe in Niagara (1953), her breakthrough picture. He was back to westerns by the '60s, working with John Wayne on pictures like The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) and True Grit (1969), after directing much of the Cinerama epic How the West Was Won (1962).

Hathaway was a reliable, well-respected director without a trace of idiosyncratic style or any identifiable obsessions, immune to the attentions of critics promoting auteur cinema. His work on Nevada Smith is certainly tight and economical. There are only two books about him I can find, both out of print and extremely expensive.

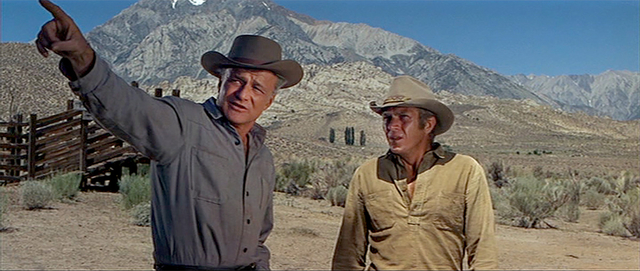

As in any hero's journey, Max must begin his with the getting of wisdom – imperative since, after directing three killers to his family, he falls in with another trio of men almost immediately afterward who leave him stranded in the desert after stealing his horse and gun. He tries to rob a lone traveler with a rusty pistol, but unfortunately the man is a gunsmith who recognizes that the gun is a) broken and b) uses obsolete ammunition.

Brian Keith plays the gunsmith, Jonas Cord, and if you've actually seen The Carpetbaggers you'll recognize him as the father of the immoral Hughesian millionaire industrialist-turned-movie-mogul played by George Peppard. (Leif Erickson played Cord Sr. in Dmytryk's picture.) He's a wise man, generous with his food but reluctant to teach Max how to use a pistol.

He knows that a boy who doesn't drink or gamble will have a hard time navigating the world of the bad men he's hunting, and additionally warns him that his quest for revenge will turn him into a man very like the ones he wants to kill. But knowing that without these skills the boy won't last long, Cord trains Max and sends him on his way with obvious regret.

The first killer Max finds is Coe (Martin Landau), now a gambler plying his trade at a poker table in a saloon. He doesn't bother with any subterfuge, simply calling him out and chasing him out the window of his hotel room into a cattle pen. McQueen had asked Hathaway the same thing he wanted from all his directors – to cut down on the dialogue in favour of action and wordless business.

Coe is good with a knife, but Max evades him by leaping back and forth across the rails of a cattle chute – the sort of physical display that McQueen loved to do in front of a camera. They finally end up in the dirt, though, and despite the wounds Coe gives him, Max drives his knife home, prompting a horrific, unearthly scream from Landau.

Max is nursed back to health by Neesa (Janet Margolin), a Kiowa woman he meets when she's working as a dance hall girl. She takes him back to her tribe's camp, where they fall in love while he recovers from his wounds. (Look for Iron Eyes Cody, the Italian-American Indian imposter, later famous for his role in environmental PSAs in the '70s, as the tribal elder.) He warns her that whatever his feelings for her, he'll be moving on as soon as he's well enough, and he makes good on that promise.

Finding the second killer requires a bit more work. He tracks down Bowdre (Arthur Kennedy) in a Louisiana state prison camp in the middle of the bayou, robbing a bank in order to get sentenced to serve hard time alongside the man, who he makes a show of befriending. It's a brutal place, run by a sadistic warden (Howard da Silva) who whips men who try to escape but – in a nod to this being a world imagined by Harold Robbins – lets them spend the night with local Cajun women who are apparently starved for male attention.

Max meets Pilar (Suzanne Pleshette), who longs to escape the bayou as much as he does, which makes her the perfect guide through its watery maze. He persuades her to get a boat and help him and Bowdre make a jailbreak, but the way she keeps asking him for reassurance ("Max – you'll treat me right, won't you?") drops a heavy hint that her story won't end well.

Sure enough, when Max takes his chance to kill Bowdre, the killer turns their canoe over, which doesn't stop Max from gunning him down. Pilar, suffering from a cottonmouth bite, realizes that Max's priority all along was revenge, and she angrily orders him to leave her alone to die in the swamp, to spare her the sin of looking at him. (Pleshette does a lot with a very little role.)

Just as Nevada Smith doesn't skimp with the cast (supporting players include stalwart character actors like Pat Hingle and John Doucette and Raf Vallone as a Franciscan priest who tries to appeal to Max's soul and give up his quest for revenge), it goes all the way with its locations, filming in the usual epic California western landscapes like the Alabama Hills, Cerro Gordo and Inyo National Park, and forcing the cast to endure real bayou heat and humidity around Louisiana's Lake Pontchartrain.

Pleshette would catch typhoid on location there, while McQueen enjoyed the perks of an air-conditioned trailer and a personal chef. Stuntman Gary Combs recalls the actor stripping off his shirt between takes, jumping on a bike and tearing up and down the trails in the woods doing wheelies. "The guy's energy level was off the wall," Combs recalled to Sandford. "It never occurred to Steve that he was putting the whole shoot at risk. I mean, if he'd got hurt we all would have been sent home."

Hathaway apparently had sufficient toughness to deal with McQueen, who loved to test the boundaries of his directors. It was a difficult enough shoot, and he knew he had to nip his star's rebel tendencies in the bud to stop it from getting worse. During a tense showdown early in production, the director laid out his requirements to his star, adding that "I'm nice to be nice to, pilgrim. I'm not nice to not be nice to."

It was apparently enough for McQueen. For the duration of the shoot the actor called Hathaway "Sir" or, when they had reached a more amicable stage, "Dad."

The final killer requires even more subterfuge to flush out; by this point Max Sand is a wanted man, and Fitch (Malden) has figured out that he's being hunted down. Max starts going by the same name, claiming to be the killer's brother, before taking on the identity of Nevada Smith and coolly evading Fitch's attempts to catch him out when he joins his gang.

The arrival of spaghetti westerns had ramped up the potential for violence in Hollywood westerns, and while much of the real brutality in Nevada Smith is either described (in vivid detail) or gets witnessed offscreen, the glimpse we get of the trio of killers as they begin torturing Max's parents at the start of the picture does just enough to amplify any further bloodshed – seen or unseen – beyond its actual depiction. Similarly the film has joined the rest of the genre in shedding rote depictions of Native Americans as enemies in favour of a far more sympathetic portrayal; morally they're on a par with Cord and Vallone's Fr. Zaccardi in their appeals to Max's better nature.

If you had recently seen (and presumably enjoyed) The Carpetbaggers, Nevada Smith might have lent a little more depth to that film's hypertrophied melodrama, and specifically the scene where Ladd's Smith, the ageing cowboy star and former outlaw living his life under an assumed name, gets into a knock-down, drag-out brawl with the son of the man who taught him to shoot and warned him about the consequences of his quest for revenge. (It would be Ladd's last picture; he was dead before it was released.)

Perhaps you might have paused for a moment to wonder at how the older Cord had failed to produce a son who shared his moral compass. If you were lucky, though, you'd have completely forgotten about the earlier movie.

Nevada Smith kept McQueen's string of hits going; it was a particular hit overseas, in India, Egypt, Latin American and Japan. (Police were called in to stop a riot in Trinidad where crowds tried to break down the doors of a movie theatre showing the picture.) But it didn't get any Oscar nominations and, once again, did nothing for Hathaway's reputation except remind producers that he was good with money, shooting schedules and recalcitrant stars.

He'd make seven more films if you count shooting the outdoor scenes in Airport (1970). His last picture was a blaxploitation picture called Hangup in 1974. He died in 1985, five years after McQueen.

During a press preview for Nevada Smith held on the Paramount lot a fire broke out on an adjacent soundstage. While the journalists were being evacuated McQueen took off his jacket and went off to help fight the fire. (An informal try-out for his role in The Towering Inferno, one speculates.) Of course this did wonders for McQueen's public image.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.