This week marked the 81st anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan. According to a fundraising article published this year by the National WW2 Museum in New Orleans, there are less than 170,000 American WW2 veterans alive today, and in just over a decade that number will be barely a thousand. God willing, I will live to see the hundredth anniversary of Pearl Harbor, and with it the sobering fact that a historical event I grew up knowing as recent history will have become part of the distant past.

It's worth remembering that 1941 was the centenary of the brief presidency of William Henry Harrison and that it was, at that point, almost a hundred years since the end of both the First Opium War and the First Anglo-Afghan War. Neither of those events would have seemed relevant at the time, but we know now that we're living through their long reverberation today.

History is experienced situationally, and something that might seem like ancient history in one place can be remembered vividly in another. The attack on Pearl Harbor and the relatively short but ferocious war in the Pacific that followed might seemed to have a line drawn under it by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from an American perspective – "mission accomplished", so to speak – but in Japan history never provided such a neat conclusion.

Kazuo Hara's 1987 documentary film The Emperor's Naked Army Marches On provides a fierce and vivid glimpse of how painful memories of the war lingered on in Japan for as long as veterans of the conflict remained vital and active citizens. It's the story of Kenzo Okuzaki, a veteran of the campaign in New Guinea, a convicted murderer and a living irritant to his nation's postwar agenda of selective amnesia.

Okuzaki was drafted in 1941 and sent to China and New Guinea, where his regiment was caught up in an Allied offensive that saw him become one of just six men from his 1,200-man regiment to survive the war. He tried to get himself killed by Allied troops but ended up a prisoner of war in Australia.

He returned to Japan and set up a car battery and used car business in Kobe but was sentenced to ten years in prison in 1956 after he attacked and accidentally killed a con man who had cheated him. Prison radicalized Okuzaki, and he began a campaign against the government and the Emperor when he was released. He was arrested again in 1969 for attacking Emperor Hirohito with a slingshot and four pachinko balls and sentenced to a year and a half in prison.

In 1976 he was arrested for throwing homemade leaflets containing pornographic images of the Emperor off the roofs of department stores in Tokyo's shopping districts and received another year and two months in prison. He was arrested again in 1981 for plotting to kill former prime minister Kakue Tanaka – once labeled a Class A war criminal – but was released without charge.

This is where Kazuo Hara's cameras introduce us to him, over the course of 1982 and 1983, which begins at a wedding between two young people involved in protests against the government. With the bride in full traditional robes, he gives a speech where he outlines his history of violent dissent and proclaims that he believes that family and nation are "against divine law." After that, Hara's camera follows him on a visit to the frail, aged mother of a young man from his company, the only one Okuzaki says he was able to give a decent burial in the chaos and carnage of their long retreat in New Guinea.

His next visit is to Yamada, a sergeant from his regiment, recovering from surgery in hospital. Okuzaki is painstakingly polite, bringing the customary visiting gift and inquiring about his health before telling the ailing man, barely visible beneath the sheets of his bed, that his illness was a divine punishment and that "for me, you are unforgivable."

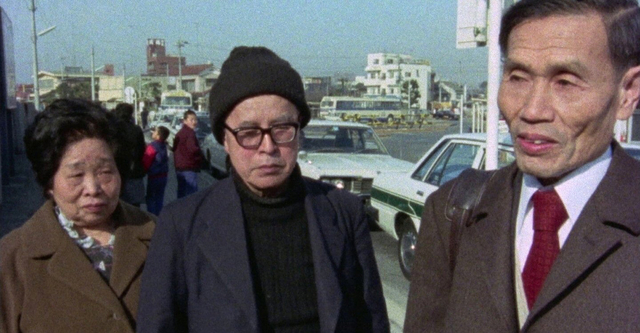

At a glance, Okuzaki is indistinguishable from any other small businessman of his generation, and the only thing that sets him apart are his vehicles – a car and a van covered in billboards and writing proclaiming the war crimes of the Emperor and his open opposition as part of his "divine crusade." Hara follows them at a distance as he makes his way across soaring new bridges and along the twisting lanes of the Japanese countryside, on the way to Okuzaki's next confrontation.

Okuzaki is particularly interested in discovering the truth behind the executions of three men in his unit for desertion in the days after the Japanese surrender. Enlisting the help of the brother and sister of two of the men, he goes about his usual plan of attack – arriving unannounced in the morning at the home or workplace of a former sergeant or senior officer.

He apologizes profusely for his intrusion, and we watch the usual formalities of Japanese society – the exchange of business cards and profuse bowing. Okuzaki is calm but persistent in his line of questioning, his voice rhythmically stating the facts as he understands them, while persistently asking the men he confronts to confirm or deny, never satisfied with an evasive answer or a disavowal or denial.

But his anger suddenly erupts when he feels he's not getting satisfactory answers; early in the film a visit to another veteran at his home turns into violence, with Okuzaki sitting on the man and slapping him before four relatives manage to pull him off. At every violent confrontation he's happy when the police are called, even offering to call them himself, under the assumption that – like when he attacked the Emperor – any trial depositions will get the facts he's pursuing on record and in the news media.

His inquisition takes a grisly turn when a series of interviews accompanied by the brother and sister reveals that cannibalism was widespread among the retreating and besieged Japanese troops in New Guinea, and that the euphemism for human meat was "wild pigs." "White pigs" were Japanese and Allied troops, and "black pigs" were native locals, though one soldier admits that "black pig" was much rare as "they ran too fast."

If you know anything about the Pacific War, this is neither shocking nor unexpected. Allied strategy early on in the campaign ("island hopping") was to isolate and bypass Japanese island strongholds with little tactical significance, knowing that every battle against the enemy would be fierce and costly. After achieving near-total control of the sea and sky early in the war, they could simply starve the garrisons on the bypassed islands or, as in New Guinea, isolate them in tiny pockets. Having begun a war with the US out of a belief that their superior esprit de corps would outweigh any obvious deficiency in supply and logistics, the Allies simply turned Japanese strategy against them; men like Okuzaki paid the price for the arrogance and incompetence of their generals and government.

That soldiers resorted to cannibalism wouldn't even have been a shock in Japan. In 1959 Kon Ichikawa released Fires on the Plain, a movie about a group of Japanese soldiers starving to death on Leyte near the end of MacArthur's campaign to retake the Philippines. Based on a novel by Shōhei Ōoka it's a shockingly graphic story, which Ichikawa cast with actors chosen for their emaciated appearance. (The lead, Eiji Funakoshi, passed out filming one of his first scenes, and his wife revealed that he hadn't eaten in two weeks to prepare for the role.)

A key part of the plot is cannibalism, with soldiers dealing in "monkey meat" they claim to obtain hunting in the forest. Funakoshi's Pvt. Tamura tries to resist the temptation – his teeth are falling out due to malnutrition in any case, and he can't chew – but it doesn't save him in the end.

Bosley Crowther of the New York Times wrote that he had never "seen a more grisly and physically repulsive film...so purposefully putrid...so full of degradation and death." The film was nominated as Japan's entry into the Best Foreign Film category at the Academy Awards but wasn't accepted. It's fascinating to think that Fires on the Plain was released the same year as A Summer Place. (A remake was made by director Shinya Tsukamoto in 2014 that apparently surpasses the grisly realism of the original.)

In 1972 Kinji Fukusaku took the money he made directing the Japanese sequences in Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) to buy the rights to Shoji Yuki's short stories and make Under the Flag of the Rising Sun, the story of Sakie Togashi, a war widow fighting to discover the truth about the death of her husband in New Guinea. It's a Rashomon-like story, with living witnesses either lying or withholding the truth about what happened while starving to death in the final days of the war.

Cannibalism is part of the story again, with soldiers dealing in meat from "wild pigs." Sakie pieces together what she can of the truth from witnesses that either lie or withhold facts out of shame or fear, but learns that Sgt. Togashi and two other men were shot as scapegoats for the breakdown of discipline, and to cover up the botched execution of a captured American pilot. She ends the film stating that the Emperor was to blame for starting an unwinnable war for whom his people were forced to pay.

The perceived wisdom when the US army of occupation took over Japan in 1945 was that the Japanese people would bear anything the victors demanded if they could keep their Emperor. This was considered necessary to maintain the legitimacy of the Tokyo war crimes trials, and to ensure the cooperation of Japan's ruling elite during the MacArthur "shogunate."

In Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, John W. Dower takes issue with this myth. Lewd jokes and irreverent attitudes toward Hirohito were one sign of popular disengagement from the Emperor's once-divine status, and US field analysts were reporting that "many people have reached a state where it is almost immaterial to them whether the Emperor is retained or not." Rumours that Hirohito's royal ancestors came from India spread in one area, with residents stating a "preference for a Japanese president rather than an Emperor of Indian ancestry."

It came down to a conflict between one school of old "Japan hands" who had close ties to the country's elite and aristocracy versus another who felt that the democratization of the country would be incomplete and the legitimacy of war crimes trials compromised if the Emperor was immune to punishment. MacArthur himself became a sort of parallel emperor, as Dower describes him:

"MacArthur played this role with consummate care. Like the emperor and the feudal shoguns, he ensconced himself in his headquarters, never associated with the hoi polloi, granted audiences only to high officials and reverential distinguished visitors, issued edicts with imperious panache, and brooked no criticism."

It was no surprise then that MacArthur sympathized with the old Japan hands, especially when it became imperative that Japan should reindustrialize rapidly to make it a more valuable American ally, even before the outbreak of the Korean War. When the occupation finally ended, Koichi Kido, former Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and a confidant of Hirohito – himself in prison as a convicted Class A war criminal – sent a message to the Emperor that now was the time to abdicate, as an act of "compliance to the truth."

If he did not, Kido wrote, "the end result will be that the imperial family alone will have failed to take responsibility and an unclear mood will remain which, I fear, will leave an eternal scar."

Kenzo Okuzaki was a living manifestation of this eternal scar. Like Sakie Togashi, he's told over and over by the men he confronts that their guilt is "just your opinion," and that it would be best to forget the past for the good of the country.

Once the subject of cannibalism is mentioned, the brother and sister of Okuzaki's dead comrades disappear from the film, and he decides to ask Shizumi, his long-suffering wife, and an anarchist friend to pretend to be them as he continues to confront the men he considers liable for the executions. It's at this point that Hara's documentary becomes fascinating, even unprecedented.

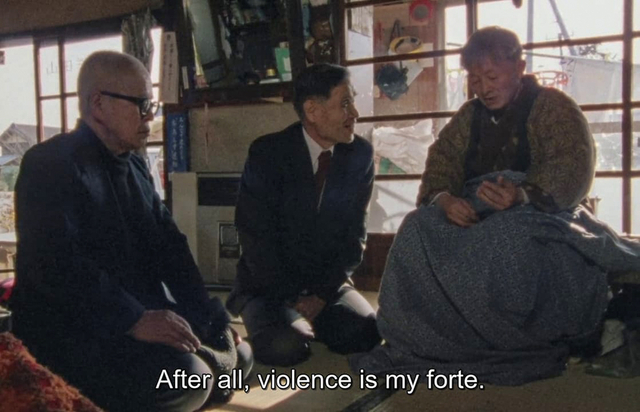

The director does nothing to hide his presence as a spectator, and the presence of cameras is frequently noted, but he remains incredibly passive in the face of Okuzaki's potential for violence. ("Violence is my forte," as the man cheerfully admits.) That he does nothing more than note Okuzaki's deception before continuing to record his confrontations makes the rest of the film a morally questionable endeavor that implicates the viewer as we continue to watch.

With his imposter witnesses in tow, he revisits Yamada, now recovering at home from his operation, and in a long scene we watch the confrontation inevitably escalate to violence. By this point our sense of Okuzaki's righteousness has been compromised; the older man has obviously tried to cope with his guilt, even writing a book about his wartime experiences, but that means little to Okuzaki, who ends up kicking his own wife in the leg while assaulting the frail, incontinent ex-soldier.

While there's no denying that Okuzaki is fighting for the sort of real truth and atonement that Japan was allowed to forgo during the occupation and subsequent economic miracle, it's impossible to deny that the man is a violent sociopath, a zealot imbued with a zealot's disinterest in means in the pursuit of their ends.

The primary quarry for Okuzaki during most of the film is Koshimizu, the commanding officer he accuses of ordering the execution of his comrades. After the chaos during his confrontation with Yamada – who ends up being hospitalized – we learn that Okuzaki tried to murder Koshimizu, but only ended up shooting his son, which led to a manhunt and earned him another 12 years of hard labour.

His wife Shizumi reads a statement that "he says the food is much better than at home and that God is with him." Another title card informs us that Shizumi died in 1986, while he was still imprisoned. He was released in 1997 and lived alone in poor health before dying in 2005.

A casual viewer might find Hara's film hard going, and even a fan of Japanese cinema and culture might struggle to make their way through its two hours. The visual rewards – often abundant in Japanese cinema – are scant, and much of the film plays out in the small, cluttered rooms of Japanese homes and office buildings.

This is the setting for as much of Japan's postwar economic miracle as the neon lights and moving billboards of Shinjuku or Ginza – the high-water marks of the country's economic triumph. The rapid revival of the two countries most to blame for World War Two – German and Japan – from rubble and poverty would set an improbable precedent for decades after the war: that the surest way to ensure economic prosperity was to lose a war with the US. Recent events in Iraq and especially Afghanistan have hopefully buried that myth forever.

But the audacity of The Emperor's Naked Army Marches On has made it a frequent choice on lists of greatest documentary films ever made, with directors like Errol Morris and Michael Moore including it among their favorites. As Japan's generation of war veterans passes, they might take with them the fervent dream of so many, not just Okuzaki, that a full accounting of the horrors and guilt of the war could shame the world into peace.

Both Japan and Germany had been constitutionally pledged to peace after the war, and pointedly denied the means to more than basic self-defence, but it's no shock that this was one of the first ideals to be gradually eroded – much to the horror of veterans like Okuzaki.

We were briefly afraid of Japan again, back in the '90s, when they seemed to be winning a capitalist game that America was starting to lose. But this was before declining birth rates and signs of decaying social cohesion became impossible to ignore. "All this is in the air now," Dower wrote in Embracing Defeat back in 1999. "No one is murmuring 'number one' any more. The uncertainty is disquieting, but the lowering of expectations is surely healthy – and yes, in other ways sad."

"The lessons and legacies of defeat have been many and varied indeed," he concluded. "And the end is not yet in sight."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.