With Mark under the weather, we apologize that we're unable to bring you our regular Hundred Years Ago Show this morning. However, we offer in its place another form of centenary content from Tal Bachman, who will be joining Mark on the upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise.

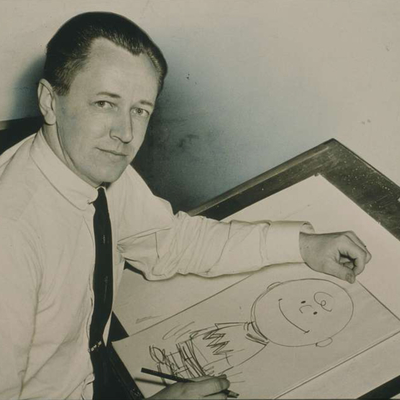

The 100th anniversary of the late cartoonist Charles Schulz's birthday came and went last week without any notice anywhere, that I saw. And so, with thanks to Mark, I pen my own little tribute here to one of the great creative geniuses in American history.

If you were young at any time between 1950 (when Schulz first began publishing his comic strip Peanuts) and 2000, when Schulz died at the age of 77, you grew up in a world in which everyone read the latest Peanuts comic strip (particularly in the US and Canada) as part of their daily newspaper reading ritual.

In that world, Peanuts comic strip panels—carefully cut from the newspaper—adorned refrigerators, bedroom walls, lockers, office bulletin boards, everywhere you went; Peanuts characters adorned T-shirts and lunch boxes; Peanuts references peppered everyday conversations; and Peanuts television specials attracted as many adult viewers as child viewers.

Most remarkably, in that world, Peanuts story lines, themes, and characters resided so deeply in the North American psyche, they had come to serve as crucial cognitive tools for enabling people to experience, make sense of, and communicate about themselves and the world around them.

On that last point, think of how many times you've said, or heard someone say, "It's Lucy with the football". The reference instantly transmits not just an insight into the true dynamics of a situation, but an insight with powerful emotional valence. In a flash, you think back to all those strips showing Lucy fooling Charlie Brown again...and you re-experience your own past feeling of wanting to believe in something so badly, you've forgotten what history has already taught you, and you've started to fall prey to the persuasions of someone who just won't deliver in the end. Think of Lucy holding that football, and you inevitably start to wonder if, in this case, you've turned into Charlie Brown. It's a reality check.

Another example is Charlie Brown's fixation on "The Little Red-Haired Girl". This elusive figure was the original Suzanne Somers in "American Graffiti"—beautiful, but much more the projected image of one's own supercharged, deifying imagination, than anything real or obtainable. "The Little Red-Haired Girl" is the gleaming prize everyone feels is out there and longs for, but always remains just out of reach. Charlie Brown never does get a chance with her.

I could list lots of other examples—Linus's seemingly pathological attachment to his blanket, or his undying, but clearly misguided, faith in The Great Pumpkin; the comfort Marcy feels in perpetual subservience to Peppermint Patty, etc. But I want to touch on a few deeper issues.

People naturally tend to think of earlier generations as somewhat benighted compared to us in our present age. We assume those before us didn't have the awareness we have, or the depth, sophistication, or imagination. And certainly, we might be tempted to imagine that about an era in which "The Andy Griffith Show", "Gilligan's Island", and "My Three Sons" were the biggest shows going, as opposed to, say, "Narcos", or whatever the latest serial killer series Netflix is running now. Or where the biggest pop stars were Frankie Valli, Dion, and Patti Page, as opposed to our present collection of convicted felons, prostitutes, drug addicts, pimps, and Satanists.

But Peanuts often went deep. One example is the daring surrealism Schulz inserted into the strip, particularly through the character of Charlie Brown's beagle, Snoopy.

Sitting alone on top of his doghouse, Snoopy regularly hallucinates himself back in time to World War I. Once there, he often finds himself in air battle as a fighter pilot. In these moments, his doghouse is no longer a doghouse. It is a Sopwith Camel outfitted with Vickers machine guns. His main job is to kill Germans (particularly the flying ace Manfred von Richthofen); but in various sequences, he carries messages through trenches filled with the wounded, gets shot down behind enemy lines, dates local French girls, and laments the deaths of his fallen comrades.

Schulz goes farther. He ends up casting these episodes as perhaps more than hallucinations. In one strip, for example, Charlie Brown stands before his school classroom to read a paper on the flu epidemic of 1918. He then reveals it was actually Snoopy who wrote it, since Snoopy was there throughout the crisis. Snoopy stands next to Charlie Brown in class, dressed in his World War I flying gear. That Schulz never definitively explains what's going on with the fantasy sequences only heightens our emotional engagement with the sequences.

Schulz even inserts Snoopy's World War I fantasy sequences into at least two of the Peanuts television specials, right in the middle of stories which had nothing to do with Snoopy or time-travel hallucinations. In this example from "It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown", Schulz interrupts a story about the kids trick or treating to show Snoopy getting shot down behind enemy lines near Verdun (see also here). Another fantasy fighting sequence appears, out of nowhere, in "A Boy Named Charlie Brown".

And in one animated sequence, Schroeder begins playing old World War I songs on his piano. As he listens, Snoopy re-experiences all the emotions of his time in wartorn France: the happy memories, but also, in the end, the sorrow of losing his friends.

But alongside the apropos of nothing war fantasies, and underneath all the jokes, runs something else weighing against our perceptions of that era. It is the dark personal struggles of the main characters themselves—most of all, of Charlie Brown and Lucy.

Charlie Brown struggles with feelings of worthlessness. Kids tease him. He seeks success, but can't find it. His great passion is baseball, but he isn't any good at it. Even his favorite baseball player, Joe Shlabotnik, can't get it together. After batting .004 for the season, Shlabotnik winds up demoted to the minor leagues. After a luckless career in the minors, Shlabotnik retires as a player and gets a job managing the minor league club, the Waffletown Syrups. Only one game into his new career as a manager, Shlabotnik gets fired after calling for a squeeze play with nobody on base.

Still, Charlie Brown never stops believing in Joe. Even after Joe gets lost in his car and misses two events at which Charlie Brown was supposed to meet him, Charlie Brown can't give up the faith. He is doomed to idolize a guy who is about as luckless as he himself is.

As for Lucy, she is vain, sociopathic, and mean. She's particularly unkind to Charlie Brown.

What Charlie Brown and Lucy both have in common is, neither is happy. Charlie Brown seeks happiness, but lacks the skills to succeed in the ways that would bring him happiness. Lucy, for her part, seems quite satisfied with her miserable self.

Interestingly, we only ever see Charlie Brown and Lucy happy in one setting: connection with Snoopy. Snoopy is the locus of happiness in the strip; he is happy within, and so, anyone connecting with him receives that happiness, too. As we've seen, he enjoys his robust fantasy life. He likes writing novels. He has a special animal friend in Woodstock. He rejoices in the natural world. He likes the food provided by "the round-headed kid" (Charlie Brown).

Snoopy's inner happiness is so radiant, it even melts Lucy's chronic irascibility. (It is Lucy who says the famous line, "Happiness is a warm puppy", after an embrace). And in caring for his dog, Charlie Brown finds purpose, as well as connection to a figure who truly appreciates him (even if Snoopy can't always remember his name).

I see I've run out of space here, and I didn't even get to any biographical stuff about Charles Schulz. So maybe you can look that up on your own. (I can also recommend the enlightening biography written by David Michaelis).

I'll just close by saying I grew up collecting the Peanuts anthologies (including Sandlot Peanuts), and spent innumerable hours living within the rich, deep, often funny, but sometimes dark, world created by Charles Schulz. During those hours, it felt like I'd become part of an ongoing story and world enough like my own so I could understand it, but different enough to broaden and deepen me. Experiences like that change you, especially when you're young. I'll always appreciate that.

And so, on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his birth (November 26, 1922, to be precise), I salute one of the great artistic geniuses in American history: Charles Schulz.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Tal know what they think in the comments below. Commenting is one of many perks that come along with Club membership, which you can check out for yourself here. Tal will be among Mark's special guests on the upcoming Mark Steyn Cruise along the Adriatic, which sails July 7-14, 2023. Get all the details and book your stateroom here.