There's a single shot, nearly an hour and a half into Michael Powell's unclassifiable 1944 movie A Canterbury Tale, that took my breath away the first time I saw it. Two soldiers – an American and a Englishman – are standing in a field at the top of a hill overlooking the famous cathedral town and pilgrimage site. The cathedral sits near the bottom of the frame, dominating the town, the men stand in the foreground, their backs to us.

But in the sky, hovering far above the town, a fleet of barrage balloons stand guard over Canterbury. You might find that view today, but you'll never see those fat, silver balloons in the sky again; the shot is a moment frozen in history, as close to a time machine as we have, of England in the summer of 1943; still at war, still unsure of victory.

Those barrage balloons were too late to stop the damage German bombers had done to Canterbury a year previous, during the "Baedeker Raids," when the Luftwaffe had targeted towns and cities of notable beauty and heritage in an attempt to break British morale. We'll see how successful they'd been later in the film, when the trio of protagonists and their erstwhile antagonist finally make it to Canterbury.

Powell's film sets the scene with painstaking effort. First there's the cathedral bells ringing, the camera panning out through a stone window down from the tall center tower over the west towers and the roofs of the town. Then a narrator begins reading from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales over a map of England, before we cut again to scenes of Chaucer's pilgrims on the road. The Falconer releases his bird, which soars into the sky and transforms into a Spitfire, before the camera cuts again to the Falconer, now in a Tommy's helmet and uniform, staring into the same sky.

Next we find ourselves on a train at night, pulling out of a blacked-out station. Two soldiers get off, one by accident. Gibbs (Dennis Price) is stationed in a camp nearby; Johnson (John Sweet) is a G.I., one of thousands arriving monthly in England preparing for the invasion of Europe. He's misheard the stationmaster's announcement of the next stop – Canterbury – and has got off at Chillingbourne, a Kentish village where we'll spend most of the film. (Keep an eye out for Charles Hawtrey as the stationmaster.)

Gibbs needs to catch a bus to his camp, but Johnson is stranded for the night, so the two of them are tasked with escorting Alison (Sheila Sim), a Land Girl just arrived in the village, to find a billet. On the way through the darkened lanes they're set upon by a man who pours glue into Alison's hair and flees. They make their way to the town hall while chasing the man, and report the incident to the local police.

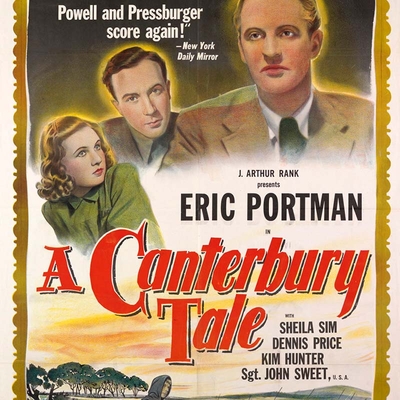

It seems that Chillingbourne is being terrorized by the "Glue Man," a vigilante who attacks young women with his glue pot in the dark, and that this is keeping the local girls away from the soldiers. Alison enlists Johnson and Gibbs to help her track down her attacker, though the likeliest suspect is introduced almost immediately – the local magistrate, Colpeper (Eric Portman), a gentleman farmer and country squire who's outspoken in his opposition to local girls stepping out on their boyfriends, fiancés and husbands who are away at war, while both town and field are filling up with British and American soldiers looking for a good time.

Powell was one half of The Archers, then just hitting their stride as a production company after the success and scandal of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp a year earlier. My dear friend Kathy Shaidle, writing about the film three years go, called it "an unflinching yet endlessly entertaining examination of what it means to be an honorable, civilized man, when that very civilization is, despite all your costly (and literally scarring) sacrifices, dying before your eyes."

This is what makes the propaganda films made by The Archers during the war stand out – enormous, often idiosyncratic style, married to an urge to make the audience just what was at stake amidst the sacrifices and miseries of the present conflict. Blimp was about the moral ecosystem that had made the war possible; A Canterbury Tale was about what particular, eternal national values, some so intangible they could only be evoked in images, were worth defending with your life.

Michael Powell was a complicated man, both professionally and personally. He was involved with two women when the film was in pre-production. One of them was Deborah Kerr, who had played three different roles in Blimp, and for whom the role of Alison was written. Her star was on the rise, though, and she was offered a contract with MGM; when he was unable to convince her to break it, Powell went off the next day and married Frances "Frankie" May Reidy, the other woman.

The role of Colpeper was written for Roger Livesey, who had starred in Blimp; the onscreen chemistry between him and Kerr was so strong that Powell had hoped for a reprise. But as Powell wrote in A Life in Movies, his 1986 autobiography: "Roger didn't understand the part, and because he didn't understand it, he found it distasteful. I knew this was a forewarning of what the critics' reception of the film might be; but I thought I could carry it off, and did not communicate my doubts to Emeric – the first and only time I did not fully confide in him."

Emeric was Emeric Pressburger, the other half of the Archers – a Hungarian-born Jew whose career as a screenwriter began at UFA in Berlin in the '20s, and who arrived in the UK in 1935 as a stateless person. He was introduced to Powell by producer Alexander Korda, and the two began a partnership that began with The Spy in Black (1939) and ended with the dissolution of The Archers after Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) – though they would reunite two more times, rather anticlimactically, to make They're a Weird Mob (1966) and The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972).

A Canterbury Tale was as personal a film as Powell had made so far in his career. He was born in Kent and was so familiar with the area around the cathedral town that finding locations was nearly effortless, though he would be denied permission to film in the cathedral itself. (How they got around this – a fascinating story about miniature bells and painted backdrops and forced perspectives – was of a piece with typical Archers ingenuity.)

"I had never made a film in the orchards and chestnut woods of East Kent, where I was born, and I couldn't resist it," Powell wrote. The main characters required some invention, but everything and everyone else couldn't have been more familiar. "The rest of the characters all marched solidly onto the screen. Didn't I know them well? Hadn't I heard them talking and seen them working when I was a child?"

"Wasn't every lane around Canterbury itself familiar to me? An artist often hesitates to use material that is too familiar to him, too near home, but now I had this feeling no longer. I was looking forward to the great swags of the laden hop-vines, to the dusty lanes with the dogrose in the hedges, to the sharp Kentish voices."

While Powell was celebrating the beauties of Kent, his partner was exiled from filming, living in a house in North Devon that Powell and Kerr had originally chosen for themselves, and which now housed Powell's wife and father, as well as Pressburger and his family.

"Percy Sillitoe, the Chief Constable of Kent, had refused Emeric permission to accompany me, or even to visit me on location," Powell recalled in his autobiography. "Kent was an area prohibited to enemy aliens, and Sir Percy stood pat on that. We pulled every string we could, but he was not to be moved. He had recently been Chief Constable of Glasgow, which probably explains his toughness."

From the moment Alison and Johnson wake up to Kent's morning sun, the film sets about enchanting us with the magic of its setting while the three young people set about solving the mystery of the Glue Man. Denied Kerr for the film, Powell had met a young couple, both actors, at a party in London – "two enchanting young people, deeply in love, and who looked as if they had just burst out of an enormous egg." She was Sheila Sim; she'd been a Land Girl at the start of the war, and he offered her the part of Alison. He was Richard Attenborough, and they'd get married before the war was over, ending life together as Lord and Lady Attenborough.

Dennis Price, who was cast as Gibbs, was the son of a general who had been invalided out of the army. Powell described him as "impudently well-mannered" – perfect for the urbanite Gibbs, a cinema organist before the war who tries to pretend that he's unaffected by the charms of the countryside.

While the military and the government had opposed Powell and Pressburger at every step before, during and after the making of Blimp, the authorities were more accommodating for the new film. They wanted to cast a real American soldier as Johnson, and there was no shortage in England at the time. Burgess Meredith, an air force officer in Britain working for the Office of War Information, was briefly considered, but they ended up with Sgt. John Sweet of the U.S. Army, who Powell had seen in London performing in a U.S.O. production of Thornton Wilder's Our Town.

At first baffled and maddened by the petty authority of minor officials, with their demands for deference and I.D. cards, Johnson is soon seduced by the peculiar charms of English country life. He bonds with the local carpenter, whose workshop is across a yard from his brother's, a blacksmith; he comes from Oregon, his family is in lumber, and the vagaries of harvesting and working with wood creates a common language.

(American viewers will be perplexed at the Oregonian Johnson's clearly midwestern accent. Sweet was born in Minneapolis, so it appears that the English, in 1943 and perhaps still today, are as unable to read American regional accents as most Americans are oblivious to the clear distinctions of English ones.)

For the young trio, Colpeper is both prime suspect and enemy, and their efforts to identify him as the Glue Man provide what passes for plot in A Canterbury Tale. Nobody was fooled, least of all Powell, who wrote that "in spite of Emeric's valiant attempts to turn it into a detective thriller, the story of A Canterbury Tale remained a frail and unconvincing structure."

There might not be much plot, but there's plenty of setting, and abundant character development. Despite a giddy, Enid Blyton-esque scene where two armies of village boys have a mock battle on the banks of the mill stream, it's still a war film, made during a war, and the spectre of death hangs over the story. The fate of the two soldiers is unknown, of course, though that of Alison's fiancé is known: a geologist who had brought her to Chillingbourne before the war, they had an idyllic two weeks in his caravan there before he enlisted as a pilot and was "lost in action."

His absence creates the void into which a tentative attraction grows between Alison and Colpeper. It begins with a scene that echoes the famous one in Pride and Prejudice, where Elizabeth Bennett's aversion to Mr. Darcy begins to melt when she gets a glimpse of his manor house. Alison sees a lovely Georgian home while driving through town on a horse cart and imagines how lovely it would be to grow old there, but discovers that it's Colpeper's house.

Their attraction might not have had as much to overcome for the audience if Livesey and Kerr had taken the roles that were written for them. Kerr always seemed more a woman than a girl, so the gulf in age between Alison and Colpeper wouldn't feel so wide. But as Powell pointed out, Portman understood Colpeper where Livesey didn't, and gave us a sense of the man deeper than mere eccentricity or moral rigidity.

This becomes apparent in the film's key scene – the same one where the two soldiers get their first view of Canterbury from that hill. The trio have definitively proved for themselves that Colpeper is the Glue Man, but before they can do anything Alison takes a walk on the Pilgrim's Road that the magistrate is always talking about, and finds herself transfixed, just as he said she would – suddenly able to hear through the wind and the birdsong the sounds of Chaucer's pilgrims emerging through time.

Startled, she calls out, only to find that Colpeper is there, lying on his back in the tall grass, reveling quietly in the landscape that he loves so palpably. The two of them sit together and talk, teasing out her grief, his loneliness, their anxiety about the troubled state of the world; their faces are close together in the frame, her head practically on his shoulder. They hide together in the grass when Gibbs and Johnson climb to the top of the hill, discussing what to do about the Glue Man. Their attraction has revealed itself, then retreated when they all know that he'll have to face the consequences of his actions.

It comes to a head the next day, when Colpeper gently forces a confrontation, unexpectedly joining the three young people in their compartment in the train to Canterbury. He's on his way to sit on the bench; Johnson is going to meet an army buddy; Alison wants to visit her fiancé's caravan, in storage in a garage in town; Gibbs intends to report Colpeper to the police before joining his unit, which is shipping out. They're all pilgrims now, Colpeper reminds them, on their way to find either blessings or penance.

The final half hour is full of the momentum and tension that the rest of the film so pointedly lacked. We get to see the damage German bombs did to the town, as the camera pans down street after street, their buildings gone, the rubble cleared away to expose basements to the sky. The pilgrims – three of them, at least – receive the blessings they didn't imagine they'd get, and the film ends on a hopeful, even spiritual note. In 1944 it was probably too much to predict victory, but Powell and Pressburger are at least sure that survival might be possible.

A Canterbury Tale did not find an audience, and Powell and Pressburger had to admit that they had made a flop. Time, however, was kinder, and over three decades later it was judged one of their best films, on par with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948).

Before then, however, they were forced to re-edit the film for American audiences, cutting its pastoral pace to a brisker clip, adding narration by Raymond Massey and new scenes with Kim Hunter as Johnson's girlfriend. The picture came out in the US in 1949 and failed to find an audience there.

In an interview in 2006, Sheila Sim speculated that the power and resonance the film seems to gather with each year has to do with nostalgia, and the sense – for its English fans, at least – that so much of what it celebrated is being lost. John Sweet, returning to Canterbury for the first time in 2001 for a special screening of the picture, told an interviewer that it took him years to understand how spiritual it was, and that it was only then that he noticed all the scenes of characters, their heads raised, looking to the sky.

Sim said that she thought A Canterbury Tale would continue to find a young audience, and like her character in the picture "most people want to find themselves and find out where they're going."

Powell, writing in A Life in Movies, said that he was grateful that he waited as long as he did to write his autobiography. "We have been privileged to live to see films which, forty years ago, we hoped, modestly, would be considered good, hailed as masterpieces. That's long enough."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.