Movie musicals are as old as sound on film, but the concert film didn't really emerge on its own until the release of Jazz on a Summer's Day, the filmed record of a long weekend's worth of performances at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. Which was fine if you were an adult or a beatnik, but the kids had to wait until 1964 to get their first concert film – The T.A.M.I. Show, a movie compiled from two concerts held at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in October of 1964. (The acronym stood for Teen Age Music International. No kid would have thought of that.)

But the rock concert film as a genre didn't really begin in earnest until the release of two films: Monterey Pop in 1968, and Woodstock, the 1970 film document of the landmark festival concert held in a farmer's field near Bethel, NY that's considered the high-water mark of '60s counterculture. The decline, so the theory goes, began four months later with another rock festival, organized by the Rolling Stones and held at a racetrack in Altamont, CA. Unlike peaceable, pastoral but muddy Woodstock, it ended with three accidental deaths and the murder of a concertgoer by Hells Angels bikers hired as security, captured on film for another concert movie, Gimme Shelter.

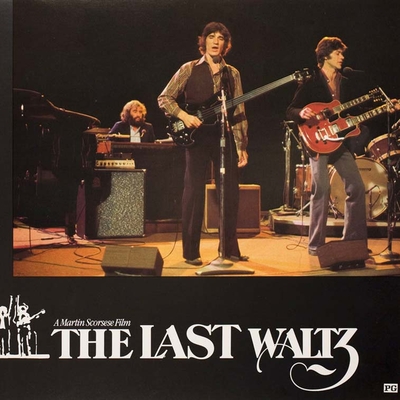

By the time Martin Scorsese agreed to work with The Band to document their swansong concert at San Francisco's Winterland Ballroom in 1976, the concert movie had established itself as an unkempt but thriving subgenre, a staple of the budding repertory cinema circuit, with films like Elvis; That's the Way It Is (1970), Celebration at Big Sur (1971), Glastonbury Fayre (1971), Sweet Toronto (1972), Concert for Bangladesh (1972), Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii (1972), Wattstax (1973), Ladies & Gentlemen: The Rolling Stones (1974), Welcome to My Nightmare and The Song Remains the Same (both 1976).

The Band had been on the road almost continuously since 1958, when they were formed as The Hawks, backup band for rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins. They toured an endless string of bucket-of-blood joints all over North America between residencies in Toronto nightclubs with Hawkins; by 1963 they were on their own, and their reputation as a crack group across several genres got the attention of Bob Dylan, who hired them as his backup band when he went electric in 1965.

This made them famous, and the release of their first two albums, Music from Big Pink (1968) and The Band (1969) made them that rarest of things: rock stars beloved by critics and admired by their most reputable peers. Their generic name – chosen after a brief flirtation with The Crackers – was a brag that they could back up onstage: for their fans and friends, they were The Band, the sort of musicians who made everyone they played with sound good.

By 1976 they were closing in on two decades on the road, and as guitarist Robbie Robertson tells Scorsese during the on-camera interviews he did with the band at their Shangri-La Studios after the concert (a former bordello in Malibu, now owned by producer Rick Rubin), it was "a goddamned impossible way of life."

"I couldn't live with twenty years on the road," Robertson says. "I don't think I could even discuss it."

The Winterland concert was planned as a grand send-off, in the first venue where they had played as The Band. With Scorsese on board, it evolved from a down and dirty filmed concert with 16mm cameras to a grand production, with multiple 35mm cameras operated by world class cinematographers like Michael Chapman, Vilmos Zsigmond and László Kovács, elaborate storyboards, a set borrowed from the San Francisco Opera, and production design by Boris Leven, whose credits included West Side Story, The Sound of Music and Star!. (Scorsese had been working with Leven on the pre-production of New York, New York.)

The concert was held on Thanksgiving Day in 1976; an orchestra was hired to play for the crowd as they ate a turkey dinner, before The Band came out to perform fifty songs, either by themselves or with guests that included Hawkins, Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Neil Diamond, Paul Butterfield, Muddy Waters, Dr. John, Ronnie Woods and Ringo Starr.

The audience was also treated to an interval of recitals from Bay Area beat poets. The only performances that survived the final edit were Michael McClure reading the introduction to The Canterbury Tales in period dialect, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti's "Loud Prayer," a satire of The Lord's Prayer. The contrast between a familiar nod to English history – probably more baffling now than when the average Eng. Lit. undergrad still read Beowulf and Piers Plowman – and a smug, sophomoric spitball at Christian belief is both evocative and telling.

I have always regarded The Last Waltz as a bookend to Monterey Pop. The earlier film caught the beautiful people of the hippie counterculture in a flattering light, as they wandered the Monterey County Fairgrounds in their beads, flowing dresses and brocaded regimental jackets, holding flowers and watching Janis Joplin and Otis Redding with wide-eyed appreciation, at the peak of the Summer of Love.

Compared to the tens of thousands of scruffy, muddy kids at Woodstock over two years later, their cars abandoned on the highway to the festival, their families left behind in some suburb, the crowd at Monterey looked like an elite – early adopters, the sort of people who'd later own wineries and invest in Apple and send their kids to a good private school with a progressive curriculum.

When Scorsese's camera rides around the streets of San Francisco, circling the block where the crowd is waiting to get into Winterland, we see similar people. The '70s haven't treated them that badly; they're there to get high, for sure, but they also know what a rare event is about to unfold. Some have responded to the evening's theme by showing up in ballgowns and evening wear. They've done some swinging and wife swapping; soon enough they might even vote Republican.

They know what good cocaine is, and where to get it.

Both films are Baby Boom productions, that generation at the start and then the peak of their cultural influence, telling their story their way. It's a privilege numbers and the economy would give them for outsized decades, ending only recently, with resentful millennials and Generation Z and their dismissive "OK Boomer" hashtag.

The all-star guest appearances were no doubt what made The Last Waltz such a major event, as a concert and a movie, but I've never thought the majority of them were nearly as enjoyable as just watching the five core members of the group playing together. The film actually begins at the end, with the band performing their first encore of the night – a cover of Marvin Gaye's "Don't Do It," before a bit of preamble and a rewind to the opening of the concert, with "Up on Cripple Creek," one of their biggest early hits.

When the show was over, Scorsese and the group shot some final scenes of the group on a soundstage. The band had decided that the concert gave short shrift to their country and gospel roots, so they decided to make that up with two extra numbers, in addition to the band performing a waltz that Robertson had written as a theme for the event.

Emmylou Harris performs with the band on "Evangeline", a song Robertson wrote the night before filming. Harris is as lovely as her voice, and the song's highlight is the duet between Harris and Levon Helm, stepping out from behind his drums to play mandolin. In style, the studio sequences are more like music videos than concert performances, with close-ups and soaring crane shots.

But the highlight of the whole film – for me, at least – is the performance of "The Weight", The Band's first single, and the song that introduced them to the world. Scorsese filmed the group on the soundstage with the Staple Singers, the family gospel group that had crossed over to mainstream success with "Respect Yourself" and "I'll Take You There", and who had covered "The Weight" on a 1968 album.

My older brother worked in the New York City office of Albert Grossman, who managed The Band along with Dylan, Janis Joplin and many other major '60s acts, so I grew up with The Band's first two records in our house, on the turntables of both my brother and sister. I've been listening to their music my whole life, and I'm still not sure what "The Weight" is about.

Robertson and the group explain that it's a surreal narrative, drawing on friends of theirs as well as acquaintances of Helm's from Arkansas, filtered through a filmmaker like Luis Bunuel and his offbeat takes on faith and sainthood. Which is a fine enough explanation, but I still listen to the song with so many questions in my head: Why is everyone so hostile? Who's Fanny? What's the Devil doing with Carmen? Why is everyone afraid of Chester, and what's the deal with his dog, Jack?

But all that disappears when I watch The Band and The Staples (their billing in the film) together. The original single had the band trading off vocals from verse to verse, but The Last Waltz adds Pops Staples, the family patriarch and guitarist, and his daughter Mavis to the mix, and they bring the song to a whole other level. Pops Staple is exactly the right man to sing a line like "Go down Moses," and Mavis is a lightning rod, channeling unbelievable energy into a song that the group had probably performed at least a thousand times by 1976.

I'm not a person in regular touch with my feelings, so a real emotional response to anything is always a jolt to my system, but watching the film again for this review elicited hot tears during "The Weight", my wet eyes a mix of both shock and shame.

Part of The Band's claim to fame is that they're one of the pillars of Americana, a name given to roots music that draws on folk, blue, country, bluegrass, gospel and R&B music, and includes artists as disparate as Wilco, the Sadies, Neko Case, Los Lobos, Steve Earle and Bruce Springsteen. That the group was comprised of four Canadians and a single American is ironic, as are recent judgments that another one of their hits performed in The Last Waltz – "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" – is problematic.

The Last Waltz was the last time Levon Helm would sing the song – apparently because of a dispute over royalties with Robertson, though keyboardist Garth Hudson claims that it was because of his dislike of Joan Baez' hit 1971 cover of the song. The song – a melancholy view of the last days of the US Civil War told by a poor white farmer – has been judged an endorsement of slavery and an apology for the Lost Cause; in an Atlantic article, Ta-Nehisi Coates called it "another story about the blues of Pharaoh."

That it was written by a Canadian, and a half-First Nations, half-Jewish one at that, is another layer of irony. Some people are baffled at how a mostly Canadian group could channel American music and folklore so convincingly, but you have to know how provincial Canada was (and, one might argue, remains) back when Robertson, Hudson, Richard Manuel and Rick Danko grew up here in the middle of the last century – and how that was a strange gift.

The further you got out of the big cities – which meant a short drive then – the more rural the country got; in essence, the more north you drove, the more Southern things were, with country bands playing taverns and pro wrestling matches in the hockey arenas. It was a country whose economy was based mostly on resource extraction, always at least a generation or more behind cutting edge American manufacturing and technology, while surfing in the wake of its postwar economic boom.

But with most of the population living within a bus ride or even within sight of America – like Hudson, in Windsor, Ontario, across the river from Detroit – or Robertson in Toronto, picking up radio stations from Nashville, we were always in thrall to American culture, despite lip service to Commonwealth status.

If context is everything, the genesis of "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" is a very thick book with footnotes, but we don't do that kind of reading any more, so it's not surprising that the song has become a target for pointed re-writes of its lyrics or outright cancellation. It's a good thing that nobody's noticed the big Confederate flag hanging on the wall of one of the rooms in Shangri-La while Scorsese interviews the band in The Last Waltz.

As for The Band, they returned to the road in 1983, without Robertson, who was apparently the only member of the group who really hated touring. Robertson and Scorsese had a kind of bromance while The Last Waltz was being edited, and Helm would later say that the director's editing made the group look like Robertson's backup band; he complained that Scorsese repeatedly made it look like Robertson (the least distinctive of the band's four vocalists) was singing when he wasn't even near a microphone.

Keyboardist Richard Manuel, the most fragile member of the group, hanged himself in 1986. Bassist Rick Danko, the hardest living, died in his sleep in 1999. Helm died of cancer in 2012. In 2022 a musical revue performing a tribute to The Last Waltz, featuring Warren Haynes of the Allman Brothers, Taj Mahal, Cyril Neville, Don Was, country singer Jamey Johnson and Canadian singer/songwriter Kathleen Edwards was touring the US.

The Last Waltz was released in 1978, after Bob Dylan extracted a promise from Scorsese and the band during a tense confrontation in the middle of the concert that they'd wait until he'd released his film, Renaldo & Clara. Four years later another concert film was released that showed how much things had changed over the turn of the decade.

If The Last Waltz bookends Monterey Pop, Urgh! A Music War is a return to The T.A.M.I. Show. Cut from concerts all over the UK, the US and in France, the film features thirty-five performances by thirty-two bands, all more or less identified by what we were calling post-punk or – more commonly – new wave music at the start of the '80s.

Many of the bands included were signed to the roster of I.R.S. Records or Frontier Booking International (F.B.I.) a record label and an artist management company run respectively by Miles and Ian Copeland, brother of Stewart Copeland, drummer for the Police, who have three songs in Urgh! and open and close the movie.

The Copelands were an interesting family, their father a CIA agent based in the middle east, instrumental in the 1953 Iranian coup d'etat. The brothers were major players in marketing punk and new wave music to the mainstream: Baby Boomers who packaged rebellious youth culture, like T.A.M.I. Show director Steve Binder and his crew from the Steve Allen Show, backed by American International, a subsidiary of MGM – an older generation selling the kids what they wanted to see, without too much attention paid to curation.

The acts in Urgh! are a wildly mixed bag, apparently chosen either by their contractual ties to the Copelands or by the simple expedience of being on tour and available for the filmed concerts. There's the Police, of course, performing in an amphitheatre built in a Roman ruin in Fréjus, on the Côte d'Azur, on their way to becoming one of the biggest musical acts of the '80s, along with a few bands that would enjoy brief but notable chart success, like the Go-Gos, Gary Numan, Devo, XTC, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, Joan Jett, Wall of Voodoo and UB40.

There are holdovers from the recent heyday of punk rock – the Dead Kennedys, Chelsea, 999, X – and post-punk bands whose reputation would grow long after they broke up (often re-forming decades later), like Magazine, Gang of Four, Pere Ubu and Echo & the Bunnymen.

And then there are novelty acts best forgotten (The Surf Punks), oddballs that didn't age well (Skafish), lovable eccentrics (John Otway, John Cooper Clarke), and Invisible Sex, a band that apparently never really existed, whose only trace is their performance in Urgh!.

And there's Klaus Nomi, a fascinatingly strange persona – imagine Struwwelpeter meets Dr. Caligari, singing opera – who needed the new wave moment to get his shot at the spotlight, but whose backup band seems to be a bunch of hippie sessions musicians in white coveralls.

(A moment of silence for Splodgenessabounds from Kent, who appear in the credits and were filmed, but ended up on the cutting room floor.)

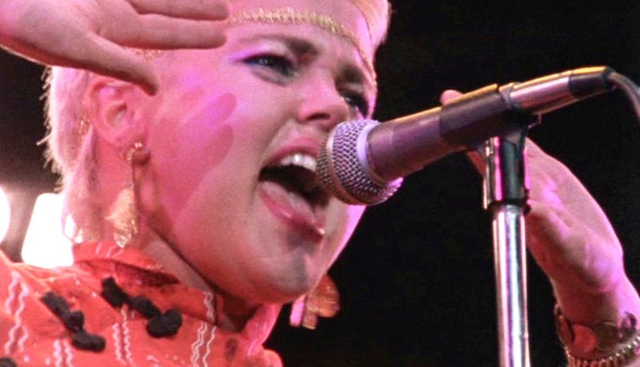

If cocaine was the drug of choice backstage at The Last Waltz – shots of Neil Young apparently had to be cut carefully to obscure the big smudge of white powder on his face – the fuel for Urgh! was cheap and effective: weed and speed, punk drugs that provided bang for the buck before heroin made its periodic and inevitable appearances, culling the herd in every town's musical scene when it did.

The performances in the film are mostly twitchy and nervous, even spasmodic, either to echo the music – Danny Elfman and Oingo Boingo and a song with far too many tempo changes – or underscore the rage and/or alienation that our generation made it a point of pride to express. Most wired of all is John Otway, vaulting and tumbling across the stage, making me cringe in anticipation of the bruises and joint pain every time he does.

With all this angst to express, it might be surprising that reggae became such a major influence on so many punk and new wave bands in the film, like the Police, the Members and UB40 (not to mention the Clash, the Ruts, PiL, the Slits, Bad Brains and many, many others). Urgh!'s frantic and ultimately exhausting pace comes to a sudden halt when Steel Pulse, an actual reggae band, perform "Ku Klux Klan" – with the band's percussionist charging onstage in a robe and pointed hood to menace the lead singer.

Even if it wasn't unfashionable at the time, the musicianship and access to grooves that made The Band so great weren't really within the musical skillset of most musicians in the punk scene; reggae was the closest we could get, although Steel Pulse's appearance is a reminder of how pale – pun intended – punk's reggae pastiches usually sounded.

When I finally saw Urgh!, many years after it first played in theatres – "real" punks didn't like being blatantly marketed to – it was to watch The Cramps, one of my favorite bands of all time, perform a typically unhinged cover of "Tear it Up." (The Cramps were basically what parents in the '50s thought their kids were seeing when they watched Gene Vincent; amazingly, they still have the same greasy charisma today, years after the death of their frontman, Lux Interior.) And I still love watching Gary Numan drive around the stage in his little cart; it's both endearing and hilarious.

My late viewing of the film finally forced me to appreciate bands I'd missed, like the Au Pairs and the Alley Cats. There seemed to be so much happening with punk and its aftermath, and only so much a poor punk kid from the suburbs could hear or afford first time around.

The fact that I can still critically parse my reaction to the bands and performances in Urgh! A Music War (yes, it's a terrible title) gives you some idea of how engaged I was with the music, then and now. I never felt the same engagement with The Last Waltz – more a sense of being a spectator to a musical moment the came and went before I knew what it was.

It was my older brother and sister's music, and while I have since been able to openly admire and enjoy The Band and many of their musical guests from The Last Waltz (Neil Young was easy, but it took many years to get over an aversion to Dylan, even longer to appreciate Joni Mitchell), I know that my brother and sister will probably never be able to return the favour with my favorite bands from Urgh! And that is how a generation gap abides.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.