Elia Kazan's life and career entered a turbulent period when he began filming Wild River on location in Tennessee in 1959. Between making the film and releasing it a year later, he turned down an offer to direct Tennessee Williams' comedy Period of Adjustment. As the director most closely associated with Williams on stage and onscreen, it was a serious decision.

As he recalled in his 1988 autobiography Elia Kazan: A Life, it was a resignation not just from Williams' play but "from the elite club of sought-after Broadway directors...By refusing the Williams play, I was, in effect, refusing all other plays by authors of similar stature. I was abdicating from the successful career I'd made. I vowed not to look back."

He had also created a way to live with the affair he was having with actress Barbara Loden. Kazan had been married to playwright Molly Day Thacher since 1932 and they had four children, but Kazan and Loden began an affair when he cast her in a small role in Wild River. Duplicity had, he wrote, "become my way of life. My efforts to conceal my infidelity were minimal; I felt no guilt."

"It was a life without excess or indiscretion. I'd become accustomed to this two-faced existence and didn't think it out of the ordinary; in fact, it seemed 'normal' to me. I'd climb upstairs to our double bed and, exhausted by my long day, fall asleep."

Since nearly everything Kazan did in his life would ultimately be read in the light of his decision to be a friendly witness at the House Committee on Un-American Activities hearings in 1952, these examples from his personal life were used by his detractors to inform and explain his moral failings in hindsight.

When he began work on Wild River, Kazan realized that he'd passed a point in his life where his mind had changed from its passionately held youthful ideals. This might explain the uneasiness that simmers under the surface of this pastoral period piece, set during the Great Depression.

The film begins with black and white newsreel footage of the Tennessee River bursting its banks, flooding towns and washing away buildings and people; a man gives raw testimony to the camera describing his three children being lost to the waters. This cuts to a small plane with the markings of the Tennessee Valley Authority, its sole passenger Chuck Glover (Montgomery Clift), surveying the river below.

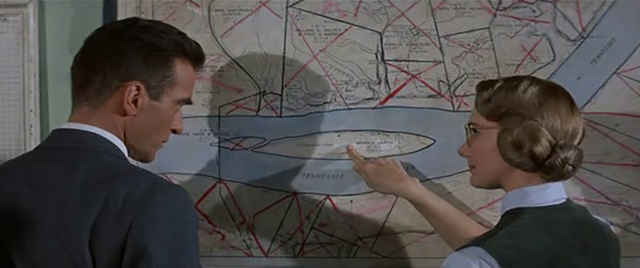

We don't get much backstory about Chuck except that he's young; it's the first thing that Betty, the secretary (played by Loden) in the Garthville, Tennessee office of the TVA notes about him. Chuck is in town with a single mission, and one that has apparently defeated all his older, more experienced predecessors.

Land on the banks of the Tennessee River was being expropriated by eminent domain to build a series of hydroelectric dams and control the seasonal flooding of the river. It would be among the largest uses of eminent domain in US history, and it remains controversial today.

The last holdouts in the area are the Garth family, holding on to their family homestead on Garth Island, and led by the family matriarch, Ella (Jo Van Fleet). In an area hit hard by the Depression – the TVA office is right next to the federal relief office, besieged by long lines of supplicants when Chuck arrives in town – Ella's stand elicits both resentment and admiration.

Chuck reacts to Betty's disparaging comments about Ella and her family by applauding her stand; it's an example of rugged American individualism, the sort of thing the country was built on. But it's necessary to the TVA and to his job that she lose.

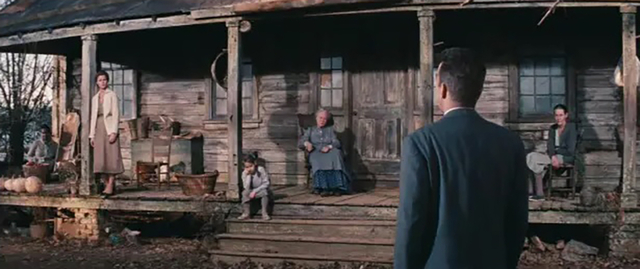

The first thing Chuck does is drive his car with its big TVA markings on the doors out to the rope ferry to Garth Island. Kazan provides a marvellous sense of place in the picture, with the camera following Clift as he walks between the lines of tall, dry corn stalks to Ella's house, knowing he's being watched the whole time.

Ella doesn't give him the courtesy of a single word, getting up from her rocking chair on her porch and walking back into the house, leaving him to plead with her granddaughter Carol (Lee Remick) and finally Carol's little girl. He's denied a chance to talk to the black workers living on the island, and learns just how simple the economy is there when Ella's sons Hamilton and Cal tell him that they don't do anything that he'd call work.

"How do you manage that?" Chuck asks.

"Just never started."

The situation frustrates and angers Chuck, who suggests that Ella might be senile or crazy. This moves Joe John, another one of Ella's sons – a giant and a simpleton, apparently – to toss Chuck into the river.

The story for Wild River was based on two novels Kazan had optioned – Dunbar's Cove by Borden Deal, and Mud on the Stars by William Bradford Huie, and on his personal experiences in the South. Kazan first visited rural Tennessee in 1937, when he worked as assistant director on People of the Cumberland, a short film written by Erskine Caldwell and meant as propaganda for US labour unions.

"I'd conceived of this film years before as homage to the spirit of FDR," Kazan wrote in his memoir. "My hero was to be a resolute New Dealer engaged in the difficult task of convincing 'reactionary' country people that it was necessary, in the name of the public good, for them to move off their land and allow themselves to be relocated."

"Now I found my sympathies were with the obdurate old lady who lived on the island that was to be inundated and who refused to be patriotic, or whatever it took to allow herself to be moved. I was all for her. Something more than the shreds of my liberal ideology was a work now, something truer, perhaps, and certainly stronger. While my man from Washington had the 'social' right on his side, the picture I made was in sympathy with the old woman obstructing progress."

The film was shot on location in Tennessee, the old downtown of Charleston playing Garthville, with Coon Denton Island, up the Hiwassee River from Charleston, as Garth Island. Kazan had been urged by his producer to cast Clift as Chuck Glover; he'd resisted at first, but came to see Clift's wounded physicality as perfect for "a rather uncertain and inept social-working intellectual from the big city, dealing with people who were stronger and more confirmed in their beliefs than he was."

"He was no longer handsome," Kazan wrote later, "and there was strain everywhere in him – even, it seemed, in his effort to stand erect. As far as my story went, he'd be no match for the country people whom he'd have to convince of the 'greater good,' and certainly no physical match for any of them if it came to violence."

Kazan knew Remick from the Actor's Studio, and had cast her in A Face in the Crowd two years earlier. A casting director at Fox had tried to convince him to choose Marilyn Monroe for the role of Carol. "Had he read the script?" Kazan wondered.

"The contrast between her sureness and Monty's insecurity was what I wanted...The contrast was so strong that at first I was frustrated and disappointed. Then I decided to go with it. In one scene Monty, at the instant of arousal, slumped to the floor. I cursed him under my breath as a limp lover. Then I decided to play the scene as it happened, on the floor at the very back of the room. I didn't move the camera closer. At twenty feet, the lovemaking seemed spontaneous and heated. Still, Lee was taking him, not vice versa. Again the accident of personality turned out to my advantage."

Remick's Carol is virtually silent when Chuck first arrives on the island. A widow with two children, she's nearly mute with depression but the arrival of the man from out of town, not to mention the imminent end of life on the island he brings with him, arouses a need to escape in her – among other things. The only problem is that she's promised herself to Walter (Frank Overton), a local businessman.

The relationship in this triangle would be the first flash of real violence in the story if Kazan had told it more conventionally – the local man made cuckold by the city slicker, the most natural flash point of violence in most Hollywood stories set in the rural South. But Overton's Walter moves past his anger to a startling sympathy for the outsider, especially when he realizes that there are other men in town with less personally at stake, more willing to escalate the situation.

Kazan might have been shedding the "shreds of my liberal ideology," but his Chuck still holds firmly on to his, angering the white men who run Garthville by filling the shortfall in crew needed to clear houses and cut trees on the expropriated properties with local black labourers – and paying them the same money as the white ones.

After a polite warning from men in suits and ties, he gets a not-so-polite one from the story's heavy, Bailey (Albert Salmi), who shows up in Chuck's hotel room one night to collect money he figures he's owed. One of his farmhands left to join the TVA crew, and then lost two days work when Bailey made him leave the crew and then beat him as punishment. He beats Chuck for the four dollars he thinks is due to him, and then leads a group of locals to Carol's cabin on the riverbank near the end of the film to scare Chuck away – not because of Ella, but because he's upset the fragile economy of the county.

Chuck even gets drunk on moonshine with Walter in his hotel room after the first beating, and has his rival drive him out to the island late that night where, staggering on his feet, he tries to explain to Ella that he finally understands that she's making her stand not because of money or hatred of progress or the government but because she wants to hold on to her dignity. Then he passes out in the dirt in front of her porch.

Clift was an alcoholic, but Kazan had "extracted a solemn promise that he would not take a drink from the first day of work until the last." He nearly managed it, making it until the last day of shooting, when he showed up swaying on his feet before passing out, just like his scene with Van Fleet and Overton on the island.

"I knew I was handling a sick man, who was goodhearted and in no way evil...I knew that each morning he underwent the humiliation of covering the transparent areas in his thinning hair with black makeup. As we went along his confidence grew, and I believe he was easier to work with in films that followed. Despite all, I felt tender toward him. He was just a boy."

Wild River would not work without the performance of Jo Van Fleet as Ella Garth, and it's a shock to realize that she was only 44 when she played the role, a woman twice that old.

Kazan had given Van Fleet her big break onscreen in East of Eden, as James Dean's mother. She would end up being typecast as mothers for much of her career, playing one in I'll Cry Tomorrow (1955), The King and Four Queens (1956), Cool Hand Luke (1967) and I Love You, Alice B. Toklas (1968).

Her big scene comes when she invites Chuck back to the island after his dunking, where he finds Ella telling her black workers why she opposes the TVA, FDR, the New Deal and progress in general. She explains eminent domain to Sam, the most loyal of them all, by telling him that she wants to buy his hound, that she gets to set the price, that the dog is for sale whether he wants to sell him or not, and that it will be sold.

(If Sam seems familiar, it's because he's played by Robert Earl Jones, whose career went back to 1939 onscreen, with roles in Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), The Sting (1973), Trading Places (1983), The Cotton Club (1984) and Witness (1985). He's also the father of James Earl Jones, and the resemblance is remarkable. Keep an eye out as well for Bruce Dern, with his first, uncredited movie role.)

A modern audience might find Wild River problematic, despite Kazan's still palpable shreds of liberal ideology, but that would be inevitable. The director is at pains to portray Sam and the other black workers in the town with respect without being patronizing, while at the same time struggling to avoid painting every white citizen of Garthville as a dyed-in-wool racist peckerwood. In his memoir he describes Loden as "a 'hillbilly' from the back-country of North Carolina."

His '30s leftist politics and time spent in Tennessee made him sympathetic to poor whites like the Garths who, despite giving their name to the island and the town, are barely better off than their black neighbours who still do the work that custom and hierarchy spares Ella's indigent sons. As with so many similar films made at the time, Kazan treads a fine line between the poles of ideological, social and racial bias; if he fails, it's likely because the true complexity of this difficult game only revealed itself in hindsight.

But it's certain that Kazan knew about difficult decisions and cause doomed to fail, especially when he gives Chuck lines like "We can't remain true to our beliefs without hurting a great many people."

Later in the film, when Chuck and Carol are trying to figure out if they have a future together, and if he even knows why he's risking his life trying to evict Ella from her island, Remick asks him "You're getting awful human, aren't you Chuck?"

While writing about the film in his memoir, Kazan writes that "perhaps I was beginning to feel humanly, not think ideologically."

"I no longer had a taste for liberal intellectuals. I always knew what they were going to say about any subject. I simply didn't like the reformers I'd been with since 1933, whether they were Communists or progressives or whoever else was out to change the world. I only believed I should like them. I'd followed the crowd, which during those years was going that way."

Chuck and the TVA win in the end, though the man from Washington tries to hold up his part of the bargain the best he can, giving Ella a "nice house," on a paved road with a radio and a modern kitchen and a porch. She still barely survives leaving the island, and dies shortly after. At her funeral in the tiny family graveyard that remains the only part of Garth Island above the water, one of her sons begins singing "In The Pines" as she's laid to rest.

It's a startling moment, or at least it was for me. Most people today know the song as "Where Did You Sleep Last Night," as performed by Nirvana during their 1993 MTV Unplugged special, six months before Kurt Cobain's suicide. It's a famously haunting performance, the singer seeming to tear the works from his throat, pausing near the end to catch his breath, his eyes darting to some unseen, terrible thing beyond the camera's frame.

The song itself was drawn from several southern folk songs known variously as "In The Pines", "My Girl" and "Black Girl", a traditional tune in the repertoires of both bluegrass musician Bill Monroe and blues legend Leadbelly. Different versions refer to Joseph Brown, a Georgia governor who leased convicts to work in coal mines. It's been recorded by King Oliver, Dolly Parton, folk singer Norma Tanega and rapper King Cudi, and like so much Southern folk culture, it's impossible to deed its origin or ownership to any race or region.

Kazan said later that Wild River was "one of my favorites, possibly because of its social ambivalence." He was not a fan of Spyros Skouras, president of 20th Century Fox, who he blamed for the film's poor reception:

"It was not exhibited in Europe until I staged a stormy scene in Spyros' office and shamed him. I hope the negative is safe in one of Fox's vaults, although I've heard a rumour that it was destroyed to make space for more successful films. This would not surprise me. Money makes the rules of the market, and by this rule, the film was a disaster."

Kazan would have his first child with Loden in 1962, while still living with his wife, Molly, who died a year later from a cerebral hemorrhage. He would marry Loden in 1967, staying married to her until her death in 1980. Kazan died in New York City in 2003. Fox did not destroy the negatives of his film.

Wild River remains one of the biggest things that ever happened to Charleston, Tennessee. Very few of the locations in the movie survive, but the town held a celebration on the fiftieth anniversary of the film's release, which produced a documentary about the importance of the filming to the locals, then and now. The spot where the rope ferry crossed from the riverbank to Garth Island was, as of 2020, a Christian non-profit campsite and ministry called Wild River Retreat.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.