Nowadays, when the best TV series on streaming services are better than almost anything in the theatres, it's hard to remember when made-for-TV movies were unmistakably second rate – the second to last destination for over-the-hill actors before their first guest shot on The Love Boat. But in the heyday of the TV movie, there were flashes of brilliance available to watch on prime time, just before the nightly news.

In the last hot flush of the Cold War, two films – The Day After (1983) on ABC, and Threads (1984) on the BBC – were both topical and popular. And an ambitious young TV director named Steven Spielberg caught the attention of the public and the movie studios with a stark action thriller, Duel (1971).

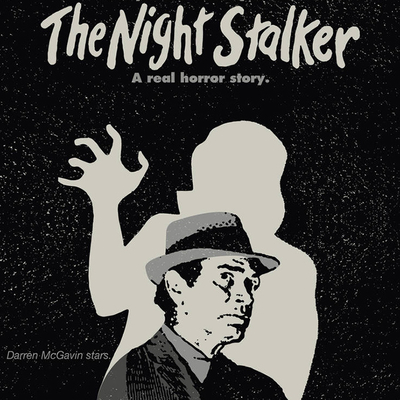

But the biggest blockbuster ratings success in the history of the made-for-TV movie came with The Night Stalker, an ABC Movie of the Week that pulled in a phenomenal 33.2 rating when it aired on January 11, 1972. (By comparison, the only program that beat it was All in The Family, then at the zenith of its popularity with a 33.3 rating, with a guest appearance by Sammy Davis Jr. that season. Brian's Song had been the biggest TV movie hit until then, just over a month previous, and The Night Stalker "blew it out of the water," as producer Dan Curtis later bragged.)

It's one thing to speculate why a more-than-faintly paranoid supernatural thriller resonated so deeply after a year of hijackings, civil wars and coups, and at the beginning of the election battle between Richard Nixon and George McGovern. It's another to acknowledge that the film was a serendipitous meeting of talents what had mostly flown under the wire until that point – none more so than The Night Stalker's unlikely leading man.

The film begins in an insalubrious hotel room, where a rumpled reporter named Carl Kolchak (Darren McGavin) is playing back a tape recording as he reviews a big story – a story so big, he says, that we probably have no idea it ever happened.

"The facts here have been suppressed in a massive effort to save certain political careers from disaster," he tells us, "and law enforcement officials from embarrassment."

The camera flashes back to the Las Vegas strip, to the corner of Casino Center and Fremont just outside the Golden Nugget Casino, where a "swing shift change girl at the Gold Dust Saloon" named Cheryl Hughes is getting hassled while waiting for a friend to drive her home. Angry and hungry, she begins walking "the eight blocks to her small frame house at the corner of 9th and Bridger."

It's a tribute to the sense of place that scriptwriter Richard Matheson puts into the story that there is such an intersection – South 9th Street and East Bridger is, in fact, about eight blocks from the Golden Nugget, in a neighbourhood that still has, today, a row of small frame houses. But Cheryl Hughes doesn't get there; taking a short cut through the inevitable and ill-advised dark alley, she's grabbed by a man who throws her around like a rag doll and advances on her with menacing intent as she lies, crumpled, on a pile of trash.

Cheryl Hughes, with her hot pants and feathered blonde hair, is just one of a series of victims of a serial killer on the loose in Las Vegas, all of whom have their blood drained from their bodies before being tossed aside like an empty soda bottle. And the first man to pick up on the connection is Carl Kolchak, a reporter at the Las Vegas Daily News, formerly a big deal journalist out east before being fired not once but twice and even three times by papers in New York, Washington, Chicago and Boston.

Darren McGavin, a veteran of the both big and (mostly) small screen by the turn of the '70s, was exactly the kind of actor who might end up in a made-for-TV movie. McGavin was born William Lyle Richardson in Spokane, the son of a traveling salesman who parked him with a family of farmers after the boy's parents divorced. He began running away, finally being sent to live with his mother in Southern California, where a job building scenery for a theatre company after college led to building sets at Columbia Pictures.

He moved to New York City and started acting, working in theatre and television there before moving back to California, where he was able to get roles in movies like Summertime and The Man with the Golden Arm (both 1955). He played the title character on Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer from 1957-1959, then got cast opposite Burt Reynolds on the NBC series Riverboat. He didn't get along with Reynolds, who left halfway through the series' two-year run, saying later that "Darren McGavin is going to be a very disappointed man on the first Easter after his death."

McGavin bounced back and forth between TV, theatre and movies (forgettable films like Bullet for a Badman (1964), The Great Sioux Massacre (1965) and Mission Mars (1968)) before being cast by producer/director Dan Curtis as Carl Kolchak in a TV movie based on an unpublished novel. Curtis had just come off the peculiar notoriety of Dark Shadows, a vampire soap opera that ran for five years on ABC, but thought he was done with both television and the movies after directing two Dark Shadows movies for MGM.

Curtis was approached by Barry Diller, the creator of ABC's Movie of the Week, who told him he had a script by Richard Matheson he wanted him to make. Matheson was something of a legend among writers working in Hollywood, and his scripts for The Twilight Zone (notably "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet") and Star Trek ("The Enemy Within") were much admired. Curtis was a huge fan, but after Dark Shadows he wasn't interested in directing and told Diller he wanted to produce the picture.

Curtis had McGavin in mind from the moment he read Matheson's screenplay, and it's hard to imagine anyone else in the role. There's his voice – smarmy and cocky, a man who's used to getting away with far more than he should. But McGavin's Kolchak did a lot to create the picture of the lowly journalist, bouncing from newsroom to newsroom, a few notches below the reputable hacks at a major daily like the New York Times, or earnest young college boys like Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, soon to remake the public image of the reporter.

Kolchak owes more than a bit to misfits with a byline like Hunter S. Thompson, right down to his white sneakers and khakis. McGavin accessorized these with a rumpled seersucker jacket and a straw hat with a wide blue and red band. (You can buy replicas of the Kolchak raffia hat online.) He travels with a manual typewriter in a case and goes everywhere with his Sony TC-40 tape recorder and various cameras – a Pentax Spotmatic and a Nikon in The Night Stalker, a Rollei 16mm subminiature in the movie sequel and the TV show that were spawned by the success of the film. Fun fact: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was published in 1971.

You understand early on that Kolchak isn't as invested in the idea of an evil and supernatural entity threatening humankind as much as he recognizes a major story – the kind of story that will propel him and his byline back into the big leagues. He knows what he's dealing with by being persistent enough to be on the scene when Janos Skorzeny, the vampire (played by Barry Atwater), fights off dozens of hospital orderlies and police, and shrugs off the multiple rounds the cops empty into him.

Like so many TV movies, The Night Stalker is filled with faces that were familiar from movies going back to the '40s and '50s, prime among which is none other than Elisha Cook Jr. as one of Kolchak's street level sources. Simon Oakland, who had appeared in Psycho and West Side Story, would play his editor, Tony Vincenzo, in the sequel The Night Strangler and the TV series that followed.

Ralph Meeker, as FBI agent Bernie Jenks and Kolchak's only ally on the side of the law, had played Mike Hammer in Robert Aldrich's Kiss Me Deadly (1955), in addition to roles in Paths of Glory (1957) and The Dirty Dozen (1967). Arrayed against Kolchak are perennial bad guy Claude Akins as Vegas sheriff Butcher and Kent Smith as District Attorney Paine; Smith was familiar from roles in The Cat People (1942), Curse of the Cat People (1944), The Trouble with Angels (1966) and the TV series Peyton Place.

Larry Linville plays a fussy coroner who feel compelled to note the draining of blood from the victims and the traces of human saliva from the wounds in their neck – not because of any prurient interest in a supernatural killer, but out of passionless medical interest. Before the year was over, Linville would be famous as Maj. Frank Burns on M*A*S*H, a character less competent but just as off-putting.

For the first and last time, Kolchak has a love interest – Carol Lynley as Gail, a pretty blonde who has some sort of unspecified job at a casino that requires wearing a silver shift. Lynley had played the pretty blonde in films like Return to Peyton Place (1959), The Pleasure Seekers (1964) and Bunny Lake is Missing (1965), and would have a major hit later in 1972 with the release of The Poseidon Adventure.

Together with The Night Stalker, this comprised a comeback of sorts for Lynley who, though twenty years younger than McGavin, seems an awful lot younger. I don't know if it was at the time, but Gail's relationship with Kolchak seems more than a little inappropriate, though the film is happy to admit that hundreds of young women working all hours at various casinos, saloons and hotels in mob-run Vegas was one of the pluses of the city for men like Kolchak – and just as likely why a vampire would set up shop there.

John Llewellyn Moxey's direction is as unfussy and straightforward as you'd expect in a film shot in twelve days for less than a half million dollars. In the day the film is bathed either in pitiless Vegas sunshine or the usual array of near-clinical TV lighting. At night the film is stygian, full of murky blacks punctured by neon and glaring banks of light bulbs, and the occasional shaft of moonlight. It's not pretty, but it's certainly effective at setting an uneasy, grimy mood.

What The Night Stalker shares with other '70s movies like, say, Jaws is a kind of misdirection. Just as Jaws isn't really about a shark as much as it's about the corrupt establishment running a summer town, happy to lose a few swimmers if it keeps the beaches open, The Night Stalker isn't really about a vampire as much as it's about a wildly corrupt town that won't even let a vampire get in the way of drawing suckers into the casinos. (There's a pun there, I'm sure, but I don't have the wherewithal to dig for it right now.)

When the establishment is forced to admit that Kolchak might be right, he makes a deal with them – he'll lead them to the vampire if they give him exclusive rights to the story. What we know – and Kolchak doesn't – is that they have no intention of holding up their end of the bargain.

After he forces his way into Skorzeny's suitably gothic hideout to make sure he's at the centre of that story, Kolchak does a victory lap, distracted long enough not to notice that his friend Bernie has betrayed him while the sheriff and the D.A. have gotten to Vincenzo and Gail, who has been driven out of Vegas before they spring their trap on Kolchak, threatening him with a warrant for his arrest for murder if he doesn't leave town as well.

"She's an undesirable element, Kolchak, and we don't want undesirable elements in Las Vegas," Sheriff Butcher tells him with a smirk, and this is why Dan Curtis admired Richard Matheson so much.

At the end of the picture I was reminded of one of my favorite memes – that it's worth remembering that the mayor in Jaws is still the mayor in Jaws 2.

When they watched the audience reaction during a test screening of The Night Stalker, Barry Diller turned to Dan Curtis and said that they should have released it in the theatres. The success of the movie led to a sequel a year later – The Night Strangler, with Kolchak in Seattle, on the trail of a vampire-like ghoul killing exotic dancers and draining their blood to make an elixir for eternal life.

In 1974 McGavin returned as Kolchak in Kolchak: The Night Stalker, an ABC series that moved the reporter to Chicago, where he worked for Vincenzo at a wire service agency. Over twenty episodes he tracked down and tried to both dispatch and get the scoop on everything from zombies, aliens, a werewolf, a lizard humanoid, a reanimated caveman and an android to Jack the Ripper and Helen of Troy. The scripts got worse and the production values declined, and McGavin complained; he was an uncredited executive producer on the series, and walked away before the first and only season was finished.

I don't think I was one of the millions who watched The Night Stalker when it first aired, but I was fully on board when the TV series debuted. It was my favorite show that year, even when I knew that the quality was going downhill. I was crestfallen when it was canceled. When I became a reporter many years later, it was still the clearest mental image I had of the job, having never met a real journalist until I became one.

Despite its flaws, The Night Stalker has had an outsized influence on horror movies and pop culture. Chris Carter was a fan, and used it as his inspiration when he created The X-Files, even persuading McGavin to play a Kolchak-like character in two episodes. Perhaps even more notable is a writer on eight episodes of the series – David Chase, who would go on to create The Sopranos for HBO nearly twenty-five years later.

People believed a lot of crazy things in the '70s – the Bermuda Triangle; ancient aliens; transcendental meditation; peak oil; that Klaatu were the Beatles; that Last Tango in Paris was a "sexy movie." But as crazy as things might have been, we were still able to understand that a vampire was nowhere near as scary as a judiciary and a government who were capable of ignoring anything as long as they could maintain their power and a sizable minority of public trust.

A kid might have thought that a Wendigo or a headless motorcycle rider were scary, but adults knew that an ambitious district attorney planning a run for congress or dreaming of a Supreme Court seat could be far more frightening. The TV series that ultimately squandered the premise of The Night Stalker failed when it forgot that.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.