The '70s, like the '30s, are a decade with a lousy self-image. W.H. Auden's confident dismissal of a "low dishonest decade" in his poem "September 1, 1939" was written before the '30s had barely breathed its last, but the '70s was only half over when director Robert Aldridge made Hustle, a film that's now called a "neo noir," about a Los Angeles cop who realizes that his private life is as dismal and compromised as his job and the city he works for.

The film begins with the sound of the wind before the camera, flying over a road next to the ocean, brings us down on a school bus. A bunch of kids are being barely supervised by the driver of the bus, a teacher or camp counselor who's more interested in listening to the music on his transistor radio. (So far, so good – for anyone who was a child during the decade, indifferent adult supervision was both a bug and a feature of growing up then.)

They finally get his attention when they find a young woman's body floating in the surf – the credit sequence ends with the director's name over an overhead shot of the watery corpse, punctuated by a shock chord on the soundtrack. This sends the camera back into the air again, to alight on an A-frame house by another beach, where Nicole (Catherine Deneuve) walks out onto the balcony for a breath of post-coital air; on the bed, her boyfriend Phil (Burt Reynolds in his brief moustacheless period) asks for a glass of milk, which prompts her to ask why sex always makes him thirsty.

By this point we know that Hustle is going to earn its "R" rating.

Their conversation lets us know her profession quick enough – she tells him that hers is "a time-honoured profession – an older one than yours." He's a cop, which we learn when he gets a call that puts an end to their day off together, something about a dead girl on a beach. He was going to take her to see the Rams versus Vikings game that day, which sends Aldrich's camera aloft again, over the stadium, to Marty Hollinger (Ben Johnson), the father of the girl in the surf, who's being called to the stadium office over the public address system.

Robert Aldrich was born in 1918 to a wealthy Rhode Island family, cousins to the Rockefellers. Family connections got him a job at RKO Pictures in 1941, after leaving college, but he chose to start his movie career at the lowest rung of the ladder he could, as a production clerk, bringing coffee and filling out paperwork. He rose quickly, though, especially after a football injury kept him out of military service and cleared the field in the studio ranks for the duration.

He started working as an assistant director to big names like Lewis Milestone, William Wellman, Joseph Losey, Jean Renoir and Charlie Chaplin, and his first job as a director came in 1953 with a low budget baseball film, The Big Leaguer, starring Edward G. Robinson. But his big break was when Harold Hecht and Burt Lancaster saw his next film, World for Ransom, which led to a long collaboration with Lancaster that began with two westerns, Apache and Vera Cruz.

You can be a big fan of any number of Aldrich films without knowing he was the director; he didn't really have a style as much as an attitude, which takes a bit of work to discover across a career that included pictures like Kiss Me Deadly, Attack, The Flight of the Phoenix, The Dirty Dozen, The Killing of Sister George, Too Late the Hero, The Longest Yard and Twilight's Last Gleaming. If his career has any consistency, it's that he was the director of the two greatest films in the brief but noteworthy "hagspolitation" genre – What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? and Hush...Hush Sweet Charlotte.

Hollinger and his wife Paula (Eileen Brennan) are taken in to identify the body by Gaines and his partner Belgrave (Paul Winfield). The older man, enraged at seeing his daughter topless on the morgue slab, decks Gaines, who declines to arrest him for assaulting an officer despite his partner's urging. "You're right," he tells Hollinger. "We should have covered her up."

There's a relentless crudeness to the world of Hustle that might shock younger audiences. Racial epithets comprise much of the cop's banter, and the criminals we glimpse during the story are a freakish lot, from the shoe sniffer to the manically laughing man in an elevator charged with "slicing up his boyfriend" to the misogynistic serial killer released on parole, who demands that Gaines is delivered to him when he starts killing his hostages at a sweatshop.

When I wrote last year about Los Angeles Plays Itself, the documentary portrait of the city onscreen, I noted that the late '60s and '70s were the zenith for showing the city as a sunny Sodom and Gomorrah: "The streets there, we understood, were full of hitmen, weirdos, mutants, basket cases, snipers, car thieves and jaded, trigger-happy cops." Hustle is fully involved in telling that story, of a city wallowing in its basest instincts, the worst excesses of the post-Aquarian malaise concentrating in one municipality.

Once Aldrich's camera alights on Hollinger at the football game, it spends most of the rest of the picture sticking close to the ground. Indoors, and away from the pitiless sunshine, the atmosphere is cave-like, with characters lit by little pools of spotlight no matter whether they're in a bar, at home, or in a police station.

The coroner's report concludes that Gloria Hollinger had died of a barbiturate overdose, but pointedly adds that the body contained traces of semen – copious amounts, in every orifice, as the cops repeat, over and over, with unseemly interest. Gaines and Belgrave's superior officer Santuro (Ernest Borgnine) is happy to let it rest with that; her parents were "nobodies" he's relieved to learn, and that's how the Hollingers are described for the rest of the picture.

While Paula Hollinger is resigned to leaving it there – "We lost her a long time ago," she tells her husband – Marty Hollinger is convinced that it was murder and a cover-up, especially when he discovers a snapshot of Gloria and her roommate poolside with a high-profile lawyer named Leo Sellers (Eddie Albert) among her personal effects.

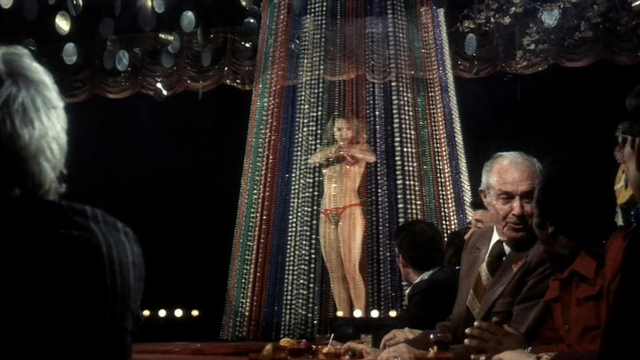

Johnson's Marty is a loose cannon – a Korean War veteran suffering from PTSD who had made his daughter his reason to live, though absent for much of her childhood working extra jobs to buy all the things the girl wanted, and "she wanted things", as several characters note. He continues digging into the case, getting beat up at a strip club where Gloria worked, despite warnings from Gaines that he's in over his head.

Gaines' partner, Belgrave, is less sure that it was just the sordid suicide of a runaway, and you can argue that the two policemen covertly encourage Marty to prod where they know they can't. They're aware of the power dynamics that run the city in ways no "white Protestant nobody" like Marty can imagine, though it's knowledge that provides neither wisdom nor comfort.

Reynolds' Phil Gaines is like Elliott Gould's Marlowe in The Long Goodbye - a man out of time, a "student of the '30s" who loves old movies, big band music and long-gone baseball players. The single happy time in his recent life is a trip to Rome, sent there by the department to negotiate with some old mafioso on a big drug bust; Nicole makes him recall the details of his trip, making fun of his terrible pronunciation but seeming to share his longing for this one, rare romantic place.

He's with Nicole because his marriage busted up when he found his wife with another man. Nicole, a high-priced call girl (could Catherine Deneuve play any other kind?) reflects on his strange double standard: "I'm a whore and it's alright. She's your wife and it's not alright."

Gaines is clearly tormented by what she does – never more so than during her nightly phone sex tuck-in appointment with a client – but can't do the one thing that will make her quit: marry and support her. Either the alimony and child support are taking a big chunk out of his cop's pay or he simply can't bring himself to make an honest woman out of a whore – even if she looks like Catherine Deneuve.

You wonder just how he's managed to maintain something like idealism in the Los Angeles of Hustle, a moral latrine where, as Nicole flippantly asserts when he wistfully complains that "she's for sale", so is everybody in Memorial Coliseum. Even his partner, troubled by guilt over the death of Gloria Hollinger, isn't above trying to beat confessions out of suspects.

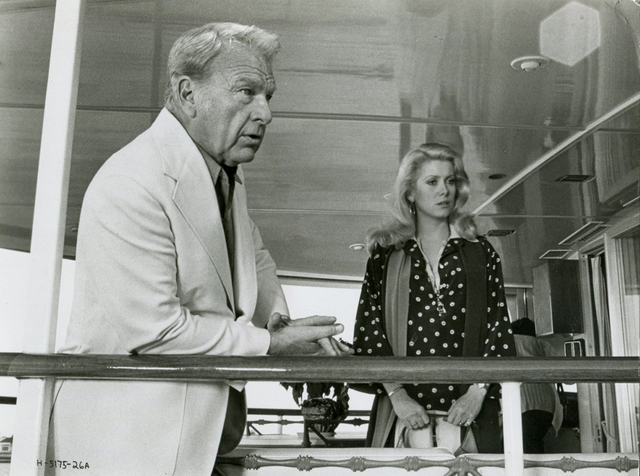

But the apex of the film's portrait of L.A.'s sleazy immorality is Leo Sellers, the mob lawyer who, we see early in the film, is a client of Nicole's, leaving her on his yacht in the marina to take a phone call that lets him know that the car bomb he ordered outside a union hall in Akron has gone as planned, killing three men.

For someone who grew up with Eddie Albert in syndication on Green Acres, it's still a shock to see him play villains – like discovering Fred McMurray's gallery of movie rogues only knowing him from My Three Sons. His Leo "the Kingfisher" Sellers is a profoundly sleazy piece of work, funding porn films on the side to meet fresh young girls like Gloria, whose nubile charms he relishes with oily enthusiasm, describing them as only an older man basking in the new rules of the sexual revolution could.

He's the obvious villain, well-connected and all the more terrible for a man like Marty Hollinger, who's tormented not just by a changing world that he finds repulsive, but how openly it mocks him. So you know that, by the end of the film, Marty and Leo will end up in the same room, with terrible consequences.

Albert had played the villain in Aldrich's previous film, The Longest Yard, which was a huge hit for Reynolds and the director. They formed their own company, Roburt Productions, to make the film, with an agreement that Aldrich would only do the film if they could get Deneuve for Nicole.

In The Films and Career of Robert Aldrich, Edwin T. Arnold and Eugene L. Miller Jr. write that "Aldrich felt, and Reynolds agreed, that an American audience would be more willing to accept the relationship if the woman were foreign, an off-handed concession to the vestigial Puritanism with which Aldrich had so often butted heads."

The murder mystery – which doesn't turn out to be much of one in the end – is definitely the weaker part of the movie, which Aldrich himself dismissed as "second-rate Kojak." His impatience with it is palpable; the film lapses into the cliches of the '70s primetime cop show over and over, kicking off a chase sequence with a shock cut and a soundtrack of funky wah-wah guitar over a straight outta Baretta montage of Gaines and Belgrave, speeding through traffic in his convertible Mustang, their voices trading dubbed wisecracks. Such moments are impossible to distinguish from a Quinn Martin production.

His obvious enthusiasm is for the character set pieces – the sorts of scenes that would get cut from primetime cop drama in the '70s if they were ever filmed at all. He lingers, fascinated, on the torturous twisting of Gaines and Nicole's relationship, where the candour with which they're willing to talk about her work is an attempt at moral sophistication that only makes things worse.

But the real emotional gold is a scene between Gaines and Brennan's Paula, who asks the cop out for a drink. She ostensibly wants to talk about the murder, and her husband, but she also flirts a bit with Gaines, who's happy to be the object of her attention. She talks about Marty's issues, his absence from her life and her daughter's, and says just enough for the cop to figure out that Gloria wasn't his child.

The scene doesn't do anything to advance the plot – only another gun fight or beat down could do that, and Aldrich doesn't have the stomach for any more – but does paint a portrait of a city and a people and a time that feel shopworn and compromised and tired. Exactly the way I remember the '70s, even seen through the eyes of a child.

You have to wonder just what sort of game Gaines and Belgrave are playing with Marty when the make him watch one of Leo's pornos – the one with Gloria and her roommate. Marty takes it better than George C. Scott in Paul Schrader's Hardcore, four years later, but it's hard not to imagine that this is exactly the sort of thing that would turn nearly any father into an instrument of wrath.

In any case, that's exactly what happens.

Reynolds was a huge star when Hustle came out, which at least made it a moderate hit in theatres, despite the R rating and the downer ending (look out for Robert "Freddy Krueger" Englund as the liquor store stickup man) that seems to come out of nowhere.

Aldrich, Reynolds and Roburt were going to make a car racing picture, Stand On It, but the usual studio complications and Hollywood egos destroyed the deal, and affected Aldrich and Reynold's friendship for years to come. The star never denied his admiration for the director, however, and in a letter to Arnold and Miller quoted in The Films and Career of Robert Aldrich, said that "he was an uncompromising individual. He did not make films for studios or for anyone else...I always admired him. In these times, and in this business, it is not easy to be true to yourself."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.