Is there a more perfect western than Ride Lonesome? Any statement like that will just prompt a chorus of disagreement, some of it outraged. ("So you've never seen The Searchers?" "Yeah, if they never made High Noon." "Sorry, buddy, but there are six films better than Ride Lonesome in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.") What I mean to say is that Budd Boetticher's 1959 film does everything a western is supposed to do with less wasted effort than any other film in the genre – and it does it in barely over an hour.

Ride Lonesome is the penultimate film in the Ranown Cycle – seven films made for Randolph Scott's production company (or some other partnership) between 1956 and 1960, beginning with Seven Men from Now and ending with Comanche Station, and which may or may not include Westbound (1959), made on contract for Warner Bros. and considered the least of the series.

The link between all the pictures is Scott and director Boetticher – as well as writer Burt Kennedy and producer Harry Joe Brown. Made in a period when westerns were considered on the decline in Hollywood, and just before Italian directors like Sergio Leone gave the genre a new, highly stylized revival, they didn't really have much critical esteem until the late '70s and '80s, when directors like Martin Scorsese started talking about them the way French critics had once lionized John Ford's films with John Wayne.

The film wastes no time setting everything in motion. The credits roll over Ben Brigade (Scott) riding a narrow trail between the rocks and boulders of the badlands of the Alabama Hills outside Lone Pine, California. He's a bounty hunter, but he finds his quarry – a snotty young gunman named Billy John (James Best) waiting for him, drinking coffee by a fire under the blazing sun.

Billy has a price on his head after killing a man in Santa Cruz, and he's let Brigade follow him for three days before making a stand. When he walks toward the young man shots ring out – there are gunmen in the rocks all around them; Billy thinks it's a great plan until Brigade reminds him that he'll be dead before his friends can take him out. The young killer curses the stupid plan and yells for his friends to go and find his brother Frank, just before Brigade puts the cuffs on him.

The whole film is built on a series of problems like this – plans, schemes, gambles or bluffs that may or may not pay off, depending on a single chance element or the nerve of the players involved. It's ultimately less about action than tension – there are really only two big shootouts in the film, while the rest of the story revolves around characters calculating odds and probabilities of success or failure. Critic Andrew Sarris would call the Scott/Boetticher films "floating poker games."

"The only trouble with Randy was, he was perfect," Boetticher told Robert Nott, the author of The Films of Randolph Scott. "He never did anything wrong." Nott recalls one of the director's favorite sayings about Scott: "If the South had had just forty Randolph Scotts, they would have won the Civil War."

Nott tried to write a conventional biography of Scott, but gave up "for several reasons, including the fact that he was so discreet that digging up anything of interest would be difficult, and, frankly, because I suspect that off-screen he wasn't all that interesting. He liked golf, gardening, sports and investing money – hardly the stuff of high drama."

Thirty-five years after Scott's death, the only really interesting thing that's written about him is his long cohabitation with Cary Grant early in their careers, which has come to be regarded – correctly or not – as a thinly-disguised romantic relationship, an open secret from Hollywood's golden age and its collection of scandals. The fact that it's still being argued about is mostly a testament to Grant's enigmatic persona and to Scott's famously taciturn nature, his aversion to doing press interviews, and an otherwise unimpeachably conventional life.

Scott was a Virginian, born to a family with money, and to an upbringing that lent him impeccable manners that were remarked on throughout his life. He joined the US Army at nineteen, ending up an artillery observer in the trenches of France during the last year of World War One. It was a formative experience, giving him access to the grim fatalism that informs so many western movie heroes.

It also provided Scott with useful equestrian training – Nott writes that he learned "to mount, ride, gallop and take off in a dead run without a saddle in order to graduate equitation classes. Likewise he was schooled in bayonetry and marksmanship, including the use of sidearms – all talents that would serve him well in Hollywood."

Brigade and Billy come across a stage coach station that's apparently empty, until two more gunmen emerge from the shadows. Boone (Pernell Roberts of Bonanza fame) and his partner Whit (James Coburn) don't seem to have any reason to be there; Boone and Brigade are acquainted, as the former is an outlaw of some sort, though the men are on amicable enough terms. Brigade is puzzling over what brought them to such an isolated place when two things happen.

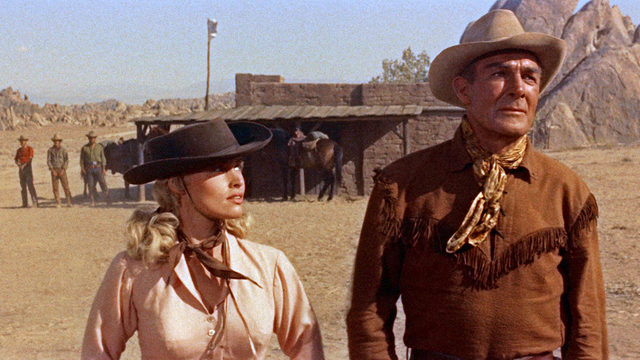

First, the station master's wife Carrie (Karen Steele) emerges with a rifle; she turns out to be pretty good with it, and tells them all to leave. Second, a stage coach comes thundering down the trail and crashes into the corral fence; everyone on board has been massacred by Mescalero Indians, which puts the men to work burying the bodies.

Carrie's husband is out chasing down horses let loose by the Mescaleros, which seems to have been just the first part of a siege of the station.

"We ain't done nothing to 'em," Whit complains, recalling that they're supposed to have a treaty with the tribe.

"We're white," Boone replies. "That's good enough"

The Indians are simply clouds of dust and smoke on the other side of the rocks while they hole up in the station overnight. Brigade tells Carrie that he has no sympathy for her husband, for taking her out to live in such a place, or for leaving her alone while he rounds up horses. For her part she doesn't understand why a man with his manners and obvious decency is in the ugly business of hunting down other men.

Steele isn't called upon to do much beyond imply Carrie's potential as a damsel in distress, or provide an object of speculation and desire for the men. Hardly a great actress, she doesn't need to do much beyond look fantastic in her gingham dress and riding clothes, and as Boetticher's girlfriend at the time, she was as qualified as anyone else for the part.

The Mescalero chief rides out to parley, and tells Brigade that he wants to trade a horse for the woman. Brigade tells her to play along and keep cool, but she loses her composure when she sees that the horse they're bargaining with belonged to her now-late husband. The Indians ride off to regroup, and begin chasing Carrie and the men across the sun-baked scrubland the next morning.

When they finally catch up with the group, there's the usual shootout on horseback where the cowboys' aim is inevitably more accurate than the Indians. Riding for the cover of a ruined building, Scott pulls off a stunt that shows off his Army training, jumping the horse over a wall and then bringing it down to the ground in a single action to dismount and take cover. It's obviously Scott – nearly sixty when he made the picture – as Boetticher always encouraged his actors to do their own stunts.

There's a shootout, with further Mescalero casualties, until the chief takes a run at the whites with a spear, which gets him shot down by Carrie and her rifle. The tribe disperses and rides away, and that's all we hear from them for the rest of the picture. It provides the requisite chase and action scenes, to be sure, but it feels like the whole sequence was simply a box that Boetticher needed to check off on the way to making a western.

Ride Lonesome gives you a sense of déjà vu if you've already seen The Tall T. The latter film has a cocky young gunman named Billy Jack, and the bad guy in both pictures is called Frank. In both films, Scott's character develops a wary friendship with an outlaw – Richard Boone's Frank in The Tall T and Pernell Roberts' Boone in Ride Lonesome, a relationship based on mutual admiration, and encouraged by the apparent desire of the outlaw for a new life. Both characters share a bemused character, quick to find the humour in situations despite their apparent grimness.

Boone has seen that one reward for the capture of Billy John is amnesty from past crimes – an opportunity he's eager for; he's got a plot of land and a place and wants to work it without worrying about being put in prison. He's even willing to share the amnesty and the land with Whit, to his partner's surprise. Coburn, in what was apparently is first film role, plays Whit as an affable dunce – the closest thing the film has to comic relief.

The problem is getting Brigade's trophy away from him. At first this means gentle pleading and the offer of assistance, then an outright buyout, and finally a plan to kill the bounty hunter before they reach Santa Cruz. As for Billy John, he's simply a commodity with an expiration date, a chucklehead and, even worse, a coward who shoots men in the back. And he isn't even the real prize Brigade is seeking.

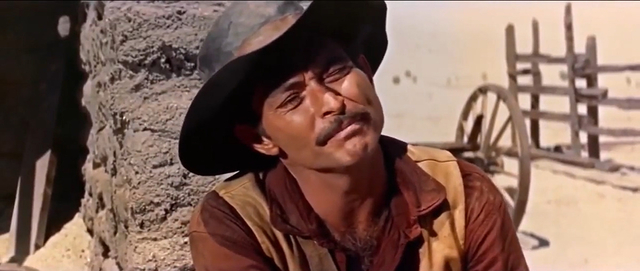

All the while Billy John's brother and his gang are closing in on them. At first we only see them as silhouettes, but when they're revealed in the bright light of day we see that Frank is played by none other than Lee Van Cleef.

Boetticher's Ranown films boosted the careers of several future stars in the roles of outlaws – Lee Marvin in Seven Men From Now, Richard Boone and Henry Silva in The Tall T, Claude Akins in Comanche Station. Van Cleef had spent the decade playing heavies, starting with his debut in High Noon, and Sergio Leone's Man With No Name trilogy would later make him a star. But he's a brief, shadowy menace in Ride Lonesome, with barely more screen time than the nameless Mescalero chief.

Van Cleef's Frank would have featured more in the film if it weren't for his fondness for the bottle, according to Nott. "He drank a lot," the writer quotes Boetticher recalling. "There were a couple of scenes in the picture where he opened his mouth and his tongue was absolutely white from the liquor, so we had to cut them out."

("The scenes, not the tongue," Nott helpfully explains.)

Reaching the scene of their showdown with the Mescaleros, Frank realizes that it wasn't Billy John that Brigade was after, but him. Boone comes to the same realization by the time their party arrives at a clearing a day's ride from Santa Cruz – a bleak opening in the pine scrub forest with nothing but a huge, dead, twisted tree in the middle: a hanging tree.

It seems the outlaw had been put in jail by Brigade when he was sheriff of Santa Cruz, and that when he was released he threatened to come back for the lawman. While Brigade waited for their showdown, Frank kidnapped his wife instead, and left her hanging from the tree. By way of an excuse, he avers that in a life full of evil deeds, he'd nearly forgotten about that one.

When I reviewed The Tall T earlier this year, I described it as "stark and underpopulated... vaguely evoking the plays of aggressively minimalist writers like Samuel Beckett or Harold Pinter." When Brigade, his prisoner and companions arrive at the hanging tree, Ride Lonesome becomes operatic – the vestiges of the oater and the cowboy shoot 'em up have fallen away, and we realize that it's a film about revenge, and our perception of justice and duty to the dead. Not as vast and epic as, say, Once Upon A Time In The West, but not a long way off. Like The Tall T and its remarkably brutal violence, the film anticipates something coming in its genre.

The end, when it comes, is both satisfying and terrible to contemplate. They ride off – Billy John to his certain death, Boone and Whit to a second chance in life (if they can keep their promise), Carrie to another man, which could even be Boone if he can make a convincing case. Brigade, however, has completed his cycle, and has become a man without a purpose. A clever viewer would suggest that Ride Lonesome is an existentialist western, and they'd back it up with a bit of dialogue right at the start of the picture:

"I don't know how much they're payin' you to bring me in," Billy John tells Brigade, "but it's not enough. Not nearly enough."

"I'd hunt you for free," the bounty hunter replies. "Let's go."

"I have always been a fatalist about my career," Nott quotes Randolph saying in a rare interview. "What was to be, was to be." Ride Lonesome was Scott's second last picture with Boetticher. He'd make just one more picture after Comanche Station – his farewell to the movie business as a star was Ride the High Country, a suitably elegiac western directed by Sam Peckinpah, and co-starring Joel McCrea. Legend has it that Peckinpah flipped a coin to decide which actor would take the lead role.

Scott could apparently be found on set reading the Wall Street Journal instead of the movie trades; he made careful investments in real estate and investments over his career, and was worth tens of millions of dollars when he retired at sixty-four. He played a lot of golf, and voted Republican. He had married actress Patricia Stillman in 1944, and they split their time between homes in Beverly Hills and Charlotte, North Carolina, where Scott was buried in 1987. The Reverend Billy Graham delivered his eulogy.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.