If you believe a recent Pew Research study, trust in government in the US is nearly at its lowest point in over sixty years. As of this spring, the percentage of Americans who "say they trust the government to do what is right just about always/most of the time" was at twenty per cent – a slight uptick from the fall of 2011, when it was at seventeen per cent, and well below the fall of 1964, when it was seventy-five per cent.

Numbers like this make public scorn for elected officials, their party apparatus and the unelected bureaucracy seem like a recent problem, but the movies tell us different. When I reviewed René Clair's 1942 comedy I Married A Witch here last year, I noted that one of the plot points was that Fredric March's character was running for governor of a New England state with the backing of his fiancée's rich and powerful father.

The existence of a political machine backing candidates was simply noted, without comment, as if viewers would simply nod at this statement of fact, much as they'd laugh when voters simply shrug after Veronica Lake's titular witch enchants the public into giving him a landslide victory, one so complete that even his opponent votes against himself.

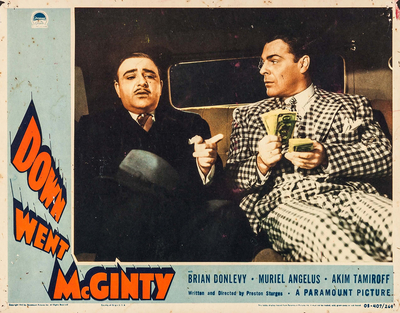

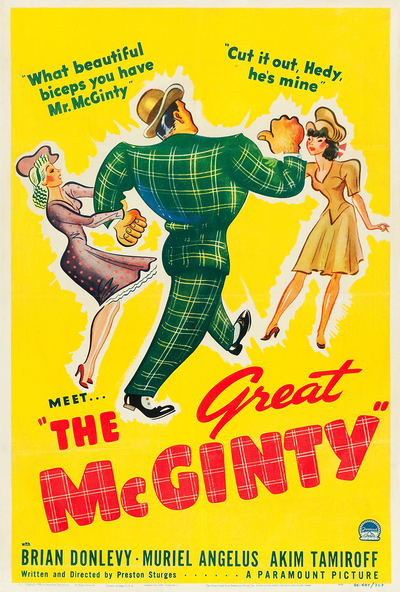

This tacit acceptance of political corruption is in place with the first scenes of Preston Sturges' 1940 comedy The Great McGinty. After a prologue in a noisy dive bar in an unnamed "banana republic," we meet the bartender, Dan McGinty (Brian Donlevy), as a vagrant in a soup line on election night in an unnamed American city (openly modeled by Sturges on Chicago, where he lived with his father as a boy.)

The cup of soup – courtesy the incumbent mayor, Tillinghast – comes with whispered instructions to go to a shed around back if you want to make a couple of bucks. McGinty obviously needs the money and meets Skeeters (William Demarest), who tells him that he can earn a deuce if he'll go and vote under the name of some poor unfortunate unable to make it to the polls.

"Maybe some of them croaked recently," Skeeters explains. "That ain't no reason for Mayor Tillinghast to get cheated of their support."

McGinty ascertains that there's no wholesale price for his repeat vote, so he takes a list of polling stations from Skeeters and manages to vote thirty-seven times before the polls close. This gets the attention of The Boss (Akim Tamiroff), the man who runs the city's political machine and his candidate, Tillinghast.

He sees something useful in McGinty, and promotes him to enforcer – collecting on delinquent protection dues owed by small business people, like Madame Juliet, the fortune teller who balks at first, but kicks loose under McGinty's verbal persuasion, even asking if he wants to "go upstairs to get your fortune told?"

(You have to wonder just who was in charge of the Production Code when lines like this breeze through so brazenly in pictures made when it was in full effect.)

The Boss sees promise in McGinty, and without any undue onscreen business gets him elected alderman, which comes with an upgrade from a loud plaid suit (described as looking like a "horse blanket") to tailored flannel, with a secretary thrown into the deal – Catherine (Muriel Angelus), who at first seems as ambitious and morally unencumbered as McGinty.

McGinty is as good at extracting graft from big businesses tendering for contracts as he was at beating protection dues out of small businessmen. Not that he needs to have his racket rationalized, but he gets it courtesy Catherine, who says that the money government extorts ultimately gets spent again anyway. But Sturges gives the greatest rationalization to Demarest's Skeeters, with the best line in the picture:

"If it wasn't for graft you'd get a very low type of people in politics – men without ambition!"

Eventually Tillinghast gets caught up in a corruption scandal, so The Boss has to cast him aside, picking McGinty to be his reform candidate. Since when did you back the reform party, McGinty asks him.

"In this town, I'm all the parties!"

The only problem is that McGinty is single, and wants to stay that way. The Boss, knowing that women voters will never elect a bachelor, launches into a homily on the sanctity and virtue of marriage, but McGinty asks why he doesn't try it.

"Because I ain't running for mayor."

Catherine offers him a solution – a sham marriage, in which she'll eagerly play the supportive wife. Having become a man of ambition, McGinty agrees, but just after the wedding learns that not only does Catherine have two children from a previous marriage, but a boyfriend – George (Allyn Joslyn), who also happens to be a lawyer.

Preston Sturges knew that his first film as a director would make or break his career, so he prepared himself for filming like an athlete would prepare for a championship game. "I went into training," he recalled. "This was the big opportunity of my life. I gave up drinking and smoking. I had a masseur waiting for me every night and when he got through with me I had my dinner in bed."

It didn't matter in the end – the stress led to a bout of pneumonia that stopped filming and put Sturges out of commission for ten days. Thankfully his illness coincided with the Christmas holidays, so only four actual days of shooting were lost. In the end, he turned in his film a thousand dollars under budget and three days early.

The Great McGinty began as The Vagrant, a play Sturges wrote in 1933, and he spent seven years unsuccessfully shopping it around to the studios, as it changed titles along the way, to The Story of a Man and then Biography of a Bum. "All the studios have said it is a fine and beautifully written script," Sturges wrote to his father, "but they find the setting too sordid and believe the story is too much concerned with politics to appeal to women."

When Paramount finally agreed to back him and his script, it was a low budget affair, with no option for any stars loaned out from other studios. Sturges had to cast from the studio's contract players, which included actors like Tamiroff, Angelus, Demarest and Donlevy, who had been mostly known for playing heavies. Many of the secondary roles – the various mugs, thugs, gunsels and hopheads McGinty encounters in and outside The Boss' organization – would end up becoming regulars in the company he'd use for his future hits (and flops), like Demarest, Arthur Hoyt, Dewey Robinson, Jimmy Conlin and Frank Moran.

Donlevy is the film's breakout performance, albeit with just a moment in a long career that included roles in pictures like In Old Chicago, Destry Rides Again, Hangmen Also Die!, The Big Combo, The Quatermass Experiment and How To Stuff A Wild Bikini. His McGinty is a proud philistine – he hates music and church bells – but Donlevy sells his gradual transition from a man desperate for any opportunity, moral or not, into one undone by a single act of integrity .

"Meat is not good for cows, whisky is terrible for goldfish," Sturges wrote in a foreword to The Vagrant, "and I propose to show that honesty is as disastrous for a crook as is knavery for the cashier of a bank."

In Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges, James Curtis quotes the film's assistant director, George "Dink" Templeton, describing Donlevy's pre-filming routine as the creation not just of a character but a different human:

"You know he had very small shoulders and he was built funny and he was short. He would come in and the first thing he would do was put in his false teeth. Then he would put on a girdle – the goddamnedest tightest girdle. He'd squeeze this thing up. He'd put on his pants and shirt and then he'd put on his platform shoes. He came in looking like he was on his knees, then he'd look like he was standing up. Then he'd put on the rug – his hairpiece – and the coat with the padded shoulders and that's what gave him that funny walk."

On his way from the soup line to the Governor's mansion, McGinty falls in love with Catherine and develops a conscience, quite against his will. As mayor, he's a one man New Deal, commissioning public works that give jobs to jobless voters – and enrich the big businesses that support The Boss, either by willing donations or extracted graft; it's Catherine's logic that money extorted is ultimately money spent, turned into a system.

But when he reaches the governor's mansion they've decided to turn their back on The Boss and push through real reforms – bills outlawing sweatshops and tenements and child labour. But McGinty has misgivings; he points out that she was never a child laborer, but he was, leaving school to support his family, in conditions that weren't anything like the dark, dank factories she's always talking about.

"And we liked it!" he insists.

Audiences in 1940 were far more likely to understand the conditions that the poor lived in, based on real experience, and in this exchange Sturges avoids talking down to them with the sort of high-minded political rhetoric that you might find in, say, a Frank Capra picture.

Political machines were real, and almost inevitably Democrat; Sturges was personally familiar with the one that ran Cook County, Illinois, as well as ones in cities like Memphis, Boston, Kansas City, St. Louis and Philadelphia, and whole states like Louisiana and Virginia, under bosses with names like Crump, Tweed, Byrd, Pendergast, Daley, Long and Plunkitt. They were the targets of reformers, and ran on reform platforms.

The most famous political machine in the US was Tammany, run out of a hall of the same name in Manhattan, and born out of the battles between Irish Catholic immigrants and Protestant "nativists" before the Civil War. In Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics, Terry Golway describes the political battleground between Tammany Democrats and the nativist Whigs, their only competition until the birth of the Republican Party.

The Whigs printed 80,000 fraudulent ballots to steal local elections in 1852, while Tammany had gangs of thugs to intimidate and arrest uncooperative voters. In 1857 the city had two competing police forces when Tammany's Municipals refused to give way to the state-controlled Metropolitan Police Department; there was a bloody riot in July of that year when the two battled after the Metropolitans tried to remove the Tammany mayor, Fernando Wood, from City Hall.

"Politics in the 1850s in New York was a crooked and violent enterprise," Golway writes. "No party and no candidate had a monopoly on the use of intimidation at the polls and the acceptance of rewards for delivering contracts."

Ultimately, the long reigns of mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and commissioner Robert Moses helped do in Tammany; they abandoned their newest Hall at 44 Union Square in 1943, just fourteen years after it was built, and Tammany's leaders moved into the National Democratic Club on Madison Avenue.

But there were still people alive who remembered Tammany as a benefactor and their voice in government, not all of them descendants of refugees from the Irish famine. "It was an imperfect institution, Tammany," writes Golway, "often egregiously so. Its alliances with gangsters and other crooked operators deserves history's rebuke."

"But after it was done and the Irish scattered to the suburbs, corruption and crooked deals did not disappear from municipal government. Mayors and lesser officials still paid attention to the needs of banking, real estate and other interests, just as surely as Charles Murphy took care to look after the fortunes of the businessmen who befriended him over dinner at Delmonico's or who bought a fistful of tickets to John Ahearn's clambakes."

In the end, McGinty rebukes The Boss, and returns the $400,000 he'd spent to elect him to the state capitol – out of funds he'd obviously salted away since he began working as his enforcer. They get into a fight, The Boss pulls a gun, gets arrested and makes good on his promise to take down McGinty if he turns on him.

The two men end up in jail awaiting their trials, but salvation arrives in the form of Skeeters, who's managed to get the job of jailer. They escape and make for a boat out of the country, but McGinty makes one last phone call to Catherine, tells her to have George get her a divorce, and where to find another stash of illicit cash he's hidden.

"Sorry it didn't work out – you can't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear."

The New York Post called The Great McGinty "a brawling, sharp-witted drama of American political corruption," while The Hollywood Reporter's review made Paramount's decision to go cheap and deny Sturges any stars look like hedging their bets:

"If Paramount had a Clark Gable to tie into the picture and maybe the name of a big feminine tar to work in his support, the picture would grab about all the coin that's waiting to be spent at the box office."

The film turned Sturges from a star screenwriter into a star director, and that was, as he'd say later, where his troubles all began. What followed were more hits – Christmas in July, The Lady Eve, Sullivan's Travels, The Palm Beach Story, The Miracle of Morgan's Creek, Hail the Conquering Hero – and then the flops, unfairly judged or not: The Great Moment, The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, Unfaithfully Yours, The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend.

So if we've always accepted the existence of political corruption, why has our opinion about it become so much less tolerant lately? Obviously, many people are only angry about it when the other side gets caught doing it, but there has to be something more in play given the steep decline in political trust over nearly six decades.

In Machine Made, Terry Solway sounds almost nostalgic over Tammany's disappearance – an emotion that can't simply be chalked up to Stockholm Syndrome after spending years researching its history. He notes that "the machine's absence left a void in New York, still a city of immigrants, and now, in the twenty-first century, many of these newcomers live in shadows that Tammany would have found unacceptable. Tens of thousands of immigrants without proper papers, without citizenship, unable to vote? Tammany's ward heelers would have seen them not as outcasts but as potential allies – and voters – and would have acted accordingly."

On the last point, recent and frequent calls for amnesty for illegal immigrants by both parties look something like his imagined Tammany solution, but they're inevitably announced with a crassness and crudely self-serving rhetoric that even Tammany would have considered cynical. But Solway goes further, and elegizes a sense of democratic complicity that the old corruption once satisfied, and which the new corruption is apparently unable to deliver to an atomized society:

"Gone, too, is the sense of participation, the connection among a block, an apartment house, a district, and those who represent them. Tammany provided spectacle, and while some of it may have been a screen for unsavory dealmaking, the chowders and the cruises and the festivals made Tammany's immigrant-stock constituents feel like New Yorkers – and Americans."

What's changed, in essence, is that corruption now exists to serve itself at our expense, with no payback or quid pro quo in the bargain. Like some kind of rogue artificial intelligence, political corruption in government has achieved sentience, and regards us less host than parasite, unable to "do what is right," as it no longer perceives voters as a threat.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.