This song is celebrating its ninetieth birthday right now, and its concerns - the Forgotten Man, the fellow who did everything asked of him and is now totally screwed - seem entirely relevant in this strange, still new millennium. Except, of course, that, if you're on the receiving end of a UK utilities bill, you might want to change the title to "Brother, Can You Spare 7,700 Quid?"

Here is how one of the biggest stars of the time introduced it on the radio:

This is Rudy Vallee stepping perhaps a bit out of character in singing a song from Americana, a song that has taken its audiences by storm, which may be explained by its theme, which is both poignant and different - 'Brother, Can You Spare A Dime..?'

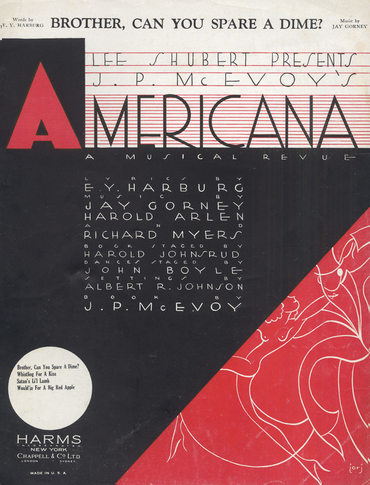

Ninety years ago - October 5th 1932 - J P McEvoy opened his third and final Americana revue at the Shubert Theatre on Broadway. It certainly didn't want for variety. The theme was supposedly the "Forgotten Man" - forgotten, that is, in the Depression - but the Forgotten Man seemed to get forgotten by a lot of other distractions in the course of the evening. There were skits about movies, and topical songs about departing mayor Jimmy Walker, and Albert Carroll doing his umpteenth impersonation of Lynn Fontanne. There were the Charles Weidman Dancers and the Doris Humphrey Dance Group doing modern dance interpretations of a prizefight and a Shaker meeting. There were (in an expansive definition of "Americana") Viennese waltzes from Alfredo Rode's Tzigane Orchestra. And, whether it was the waltz fans who didn't care for the Shaker dance or the interpretive prizefight ballet devotees who weren't into the topical songs, Americana did not linger long on the Great White Way.

Yet one artefact emerged from the surrounding rubble, and has endured for almost a century. There was a breadline sketch in the show. Satirical stuff: William Randolph Hearst had the biggest, best-ordered breadline in New York City, so in Americana someone played Mrs Ogden Reid of the Herald Tribune flying into a snit because Hearst had a better breadline than hers. Etc. But, with all the Depression humor, they needed a song on the theme. The show had all these unemployed men standing around in their old army uniforms, and among their number was Rex Weber. He was a comic, but there was no joke in the song. He sang it straight:

Once I built a railroad

Made it run

Made it race against time

Once I built a railroad

Now it's done

Brother, Can You Spare A Dime...?

For the critics, it was the highlight of the evening. The song, declared Theater Arts, "deflates the rolling bombast of our political nightmare with far greater effect than all the rest of Mr McEvoy's satirical skits put together." To Brooks Atkinson in The New York Times, "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" "expressed the spirit of these times with more heartbreaking anguish than any of the prose bards." Rudy Vallee took it up on the radio, and within weeks Bing Crosby and Al Jolson had made records, the first of a long sustained multigenerational line of interpreters all the way down to George Michael and Mr Burns on "The Simpsons":

"Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" became "the anthem of the Depression" in part because it's an uncompetitive category. There are plenty of songs of the period in which the period - the times, the sensibility - is present: "We're In The Money ...and when we meet the landlord/We can look that guy/Right in the eye", and, even if we're not in the money, we can dream of it and "Baby, what I wouldn't do/With Plenty Of Money And You", or even "A Cup Of Coffee, A Sandwich And You", because "Who Cares what banks fail in Yonkers/Long as you've got a kiss that conquers?"

But, with the exception of "Remember My Forgotten Man", powerfully sung by Joan Blondell in Golddiggers of 1933, almost every other song of the Depression treats the Depression as merely another pretext for romance, like the moon in June. The authors of "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" addressed the subject head on.

They weren't famous songwriters. The lyricist, Yip Harburg, had found himself on the receiving end of the Depression. He was in the electrical appliance business, which was a good business to be in as America electrified. But not good enough to withstand the Crash in '29. Harburg was thirty-three, and he had nothing left. Not true, pointed out his old classmate Ira Gershwin. "You've got your pencil. Get your rhyming dictionary and go to work."

"I decided," said Harburg, "to give up this dreamy stuff called business and do something realistic like writing lyrics."

The first thing a lyricist needs is a composer, and Ira introduced Yip to a fellow called Jay Gorney, born the same year as Harburg - 1896 - not on New York's Lower East Side but in Bialystok. Daniel Jacob Gornetzky spent his first ten years in Russia, until a brutal pogrom sent his family scuttling to the new world. By the Twenties, he was a jobbing songwriter, trying to get a break in Tin Pan Alley or on Broadway. His songs "Zulu Lou" and "Bom- Bom-Beedle-Um-Bo" were both interpolated into The Greenwich Village Follies of 1924, but not to any great effect.

Gorney didn't need a Depression to be out of luck. At the opening of a subsequent show, Hoopla, Bernard Granville came out drunk and stretched his two-minute prologue to over an hour, after which a scenery malfunction caused another delay of forty minutes. At the end of Act One, only ten minutes remained before the start of union overtime, and when, at the end of intermission, only seven theatregoers returned for the Second Act the producers figured it was cheaper to pay them off.

Gorney was philosophical. "We just set a record for the shortest run in the history of the theatre," he said. "One act."

His next show, Merry-Go-Round (1927), included "Hogan's Alley", the song which made Libby Holman a star, and "Moskowitz, Gogeloch, Babblekroit and Svonk", a quartet for ambulance-chasing lawyers. But you get the picture: in 1932, Jay Gorney wasn't exactly a hit machine.

He did, though, have a tune Harburg liked. Americana required a song for the breadlines, and Yip thought he'd found one. In his biography of his father, Who Put The Rainbow In The Wizard Of Oz?, Ernie Harburg includes an Associated Press photograph of Times Square at night in 1932. It would have been the scene Yip saw heading home from the theatre every evening: The lights of the Great White Way and thousands of folks standing in line, as if waiting for tickets at the half-price booth, or seats for a gala performance of Les Miz or Hamilton. But, in fact, the theatregoers are the ones scurrying past. As the picture caption puts it:

In strange contrast to the dazzling bright lights of Broadway and the well-clad, well-fed throngs that flow past them, hundreds of hungry men stand shivering nightly waiting their turn for a sandwich and a cup of coffee.

Harburg didn't have to look far for his title. On every block in every direction around the Shubert Theatre there'd be some guy saying, "Can you spare something for a cup of coffee?" or "Can you spare a dime?" So he had his hook, and there was a tune of Gorney's he thought would be perfect for it. The only trouble was it already had a lyric, a journeyman torch song by some earlier writing partner:

I will go on crying

Big blue tears

Since you said we were through

I will go on crying

Big blue tears

Until all the seas run blue...

"Jay," asked Yip, "is this lyric wedded to this tune?" "Well, said Jay, "we can get a divorce if you have the right tactics." And Yip said, "I've got a title for it: 'Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?'" If you so desire, you can still sing the "Big blue tears" lyric to the tune: it's a useful reminder of how, in songwriting, marital mismatches are the rule more often than not.

Do you know how hard it is to write a song for beggars, for panhandlers? A guy telling you he's lost his job and he's got a wife and five kids and one of 'em's sick may work when he's standing in front of you on the sidewalk, but in a song self-pity is all but unsellable - unless it's Johnny Mercer's lyric for "One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)", which works as a kind of parody of the maudlin self-pitying drunk boring the bartender. Harburg knew what he had to avoid but wasn't so sure what to put it in its place. He was a satirist and he didn't always know quite when to rein it in. Having come up with a hit title, he nearly threw it away, getting detoured into the usual savage indictment of the usual suspects. Thus, he had a stanza or three in which John D Rockefeller condescended to some laid-off workers:

Once you drilled an oil well

Made it gush

How Socony did climb

Once you drilled an oil well

Now I'm flush

Brother, here's a brand new dime...

Satire, said George S Kaufman, is what closes Saturday night. And that would have been the fate of "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" had Harburg followed his satiric instincts. Yip kept very detailed worksheets, and in their book Ernie Harburg and Harold Meyerson give a fascinating glimpse of how the final lyric emerged. Having forsworn Rockefeller-baiting, he turned to imagery: "The mills of the east and west/The forges of the north and south." But they're the catchpenny generalities of ersatz folk song, a paean to the industrial heartland by one who sounds only hazily acquainted with it, the sort of sentiment best left to the Pete Seegers.

"The poet," said Goethe, "should seize the Particular, and he should, if there be anything sound in it, thus represent the Universal." That's what Yip Harburg eventually did: he seized the Particular, blazing and vivid, and thus represented the Universal. It took a while. He started with "I once built a railroad", switched it to "Once I built a railroad", and found he had the structure for the whole lyric:

Once I built a tower

To the sun

Brick and rivet and lime

Once I built a tower

Now it's done

Brother, Can You Spare A Dime...?

There were accountants and bellhops and even electrical appliance salesmen out of work. But in confining the detail to construction Harburg was very artful: These are the people who literally built the country. They built a railroad, spike after spike across the continent, binding the nation. They built the glittering skyscrapers of its great cities, reaching to the sky, and now they've fallen as low as you can go. They built it all, and now it's done, and they're done, too. Is it the same guy? Worked for Union Pacific, then moved to urban development? Don't be so literal. Harburg's found the voice of Everyman, and in the middle section he kicks it up another notch:

Once in khaki suits

Gee, we looked swell

Full of that Yankee Doodly-dum

Half a million boots

Went sloggin' through hell

And I was the kid with the drum...

Lyric-writing is the art of compression, and that release is beautifully done. It's the Great War, but he never refers to it as such, and "Half a million boots/Went sloggin' through hell" conjures it as brilliantly as anything: It reminds us that this vast army - of the unemployed, of breadline shufflers, of beggars, nobodies, nothing - used to be another kind of army, not so long ago. Most arrangements of the song can't resist taking their cue from the drum and evoking the snares and bugles of a marching band. Even pared down acoustic-guitar versions do it. Gorney's music is stirring, but what's impressive is that by this stage in the song it seems perfectly natural that a song for the unemployed should be dignified and martial.

The composer drew the tune from some half-remembered Russian melody of his childhood; it's very Jewish, the lead phrase of the main theme stepping up the first five notes of the minor scale: "Once I built a rail-". You can hear real pain in the music, which is presumably why Gorney originally thought it would be just right for a torch ballad. The song is also distinguished by an unusually good verse, which is musically oddly tentative and uncertain, matching the bewilderment of the lyric:

They used to tell me I was building a dream

And so I followed the mob

When there was earth to plow or guns to bear

I was always there

Right on the jobThey used to tell me I was building a dream

With peace and glory ahead

Why should I be standing in line

Just waiting for bread?

You can appreciate why singers like it. Instead of the usual and-that's-why-I-sing warm-up of most Broadway verses, this one ends on a great howl of pain. A quarter-century or so back,Yip Harburg's son Ernie sent me a CD of a couple of dozen versions of "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?", old and new, from Phil Harris to Barbra Streisand to Tom Waits. I noticed a couple of things. First, for such a bold clear lyric, an awful lot of singers can't seem to sing it straight: There's a whole bunch of guys who, in "brick and rivet and lime", replace "rivet" with "mortar": Leaving aside any structural issues, "rivet" is just a much meatier word on those notes. And then there are others who sing "Gee, we looked fine" instead of "swell" and don't even notice they've got nothing to rhyme with "hell".

Some of the lyrical confusion can be laid at Harburg's door: Is it "Brother, can you spare a dime?" or "Buddy, can you...?" Answer: Both. The lyricist used "Brother" for the first two sections, but switches to "Buddy" for the very last line. The second thing I spotted took longer to sink in. This number is more popular with the post-rock generation than most "Great American Songbook" fare, for obvious reasons: it's about social issues rather than boy-meets-girl. So, from the Sixties on, it was embraced by Judy Collins, Peter Yarrow and a bunch of other folkies. Most of the contemporary performances feel a little bloodless to me, as if their insistence on its relevance to whatever was going on when they recorded it has blinded them to its awesome power as written. By contrast, the two biggest hits first time round in 1932, by Bing Crosby and Al Jolson, remain profoundly moving and, despite rather four-square orchestrations, among the best things either man ever did. If I had to pick one over the other, I'd probably plump for Jolson:

Why did he do it? Was he trying to carve out a niche after "Hallelujah, I'm A Bum"? Or was it just that the lyric line "Say, don't you remember? They called me Al" was an invitation he couldn't resist? Whatever the reason, all the old mammy hamminess that seems so dated on his core repertoire and rather wearying over the course of a full album is turned amazingly real. It's almost as if the truth of the song is so potent it can transform even the hokiest mannerisms. In the second chorus, Jolson does his spoken-lyric shtick and his mumbled extensions of the title phrase - "Say, brother, you ain't got a dime about you, have you?" - are oddly effective. Yip Harburg once produced one of the best-ever definitions of song, of the combination of music and lyric: "Words make you think a thought. Music makes you feel a feeling. Song makes you feel a thought." That's certainly what "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" does. Jolson doesn't do as good a job as Bing wailing "I'm your pal", but his final line is a great primal cry that distills the era:

Say, don't you remember?

They called me Al

It was Al all the time

Say, don't you remember?

I'm your pal

Buddy, can you spare a dime?

That's a terrific ending: At one point, a quarter of the workforce had been laid off. What determined whether you wound up among the 25 per cent on the breadline or the 75 per cent still in work? There were a lot of half-forgotten buddies among the anonymous faces in those lines. What did the old pals do? Pull the cap down and pass by? There weren't a lot of dimes to spare in those days, even if you were in work.

"Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" gave Gorney and Harburg their first and only hit, before circumstances set them on separate paths. Yip went on to a career that included one of the great film scores (The Wizard Of Oz) and one of the most musically satisfying show scores (Finian's Rainbow) and plenty of great individual songs in between - "April In Paris", "It's Only A Paper Moon", "Last Night When We Were Young". Unlike chums such as Ira Gershwin, he was an avowedly political writer. In the Seventies, The New York Times asked him to update "Brother" for a new age, and he responded:

Once we had a Roosevelt

Praise the Lord!

Life had meaning and hope

Now we're stuck with Nixon

Agnew, Ford

Brother, can you spare a rope?

If you'd been on those breadlines in 1932, you might well conclude that happy is the land whose biggest problem is Gerald Ford.

As for Jay Gorney, he moved to Hollywood, set the Bill of Rights to music for the Department of Education, and wrote and produced a string of "B" pictures including Moonlight And Pretzels, The Gay Senorita and Hey, Rookie! (1944), in which Ann Miller, in Gorney's "Streamlined Sheiks" number, set a world record of 550 taps per minute. But his greatest achievement on the coast was the foresight he displayed at the box-office of 42nd Street, where he spotted a little girl gazing up at the photograph of Ruby Keeler and humming and tapping:

'I stopped and said to my wife, 'Have you ever seen a cuter child?'

'She's adorable,' she said...

Well, I don't usually talk to strange little girls, but this one was just charming, so I went up to her.

'Hello,' I said. 'What's your name?'

'Shirley.'

'What's your last name?'

'Temple.'

Gorney secured her a part in Stand Up And Cheer, wrote her a song called "Baby, Take A Bow", and the rest is history. His own daughter, Karen Lynn Gorney, eventually found her way into movies, too, partnering John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever. The fever has now passed and these days she does a rather nice take on "Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?" Her dad wrote one other top-dollar song, "You're My Thrill", which Joni Mitchell did a searing version of a few years back. But, compared to Harburg's catalogue, it's thin pickings. Lee Shubert, the producer of Americana, once asked Gorney, "Do you have another song like "Mister, Will You Give Me Ten Cents'?"

No, he didn't. Unlike the dopey nursery jingles of "This Land Is My Land" and its ilk, the composer had given one of the protean "protest songs" better music than most social protest ever gets, and he never wrote anything like it again.

And why did Gorney and Harburg bust up? Well, it was romantic complications. Edelaine Gorney split from Jay and eventually went on to marry her ex-husband's ex-lyricist, Yip Harburg.

As the former Mrs Gorney and latter Mrs Harburg liked to put it:

I never married a man who didn't write 'Brother, Can You Spare A Dime?'

~Many of Steyn's most popular Song of the Week essays are collected together in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are available from the SteynOnline bookstore - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter the special promo code at checkout to enjoy the special Steyn Club member discount. As we always say, club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Sunday song selections. And we're proud to say that this site now offers more free content than ever before.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

Members of The Mark Steyn Club get to have at it in our comments section. So, if you think you can spare us your ten cents, brother, get typing below. For more on The Mark Steyn Club, see here.