It's only been a few years now since I finally lost the sensation that the year began in September, and not in January – a feeling deeply impressed into my brain by school, and which took longer to lose than the actual number of years I spent as a student. It's a trivial thing, to be sure, but it makes you wonder just what other habit or belief our school years press deep into our mind, and which we might never escape.

Writing about school here two years ago – and the ambivalent, sometimes angry attitudes it elicits from us – my friend Kathy Shaidle wrote that the "thoughtless lip service we pay to the high-minded, 'progressive' concept of mass public education is not reflected in the broader popular culture, where the Truth (or something like it) frequently seeps out between the cracks of our unexamined platitudes." Which is to say that not everyone hates their memory of their school years, but that enough of us do to create what Kathy called the "Blow Up Your School" sub-genre of movies.

Back when we were just getting to know each other, my wife and I suggested we share with each other our formative teen movies – the films that resonated most with us during that time of our lives before we'd met. She kicked off with Pretty In Pink, which I'd never seen – the four year age gap between us meant that I'd missed the whole John Hughes moment.

I volleyed back with a film that summed up nearly everything I remembered about the private Catholic boys' school I attended for five years. I was surprised at how well it held up, but when the credits rolled my future wife sat on the couch in quiet shock. That was, she said, one of the most awful, terrifying movies she'd ever seen, and she was concerned at how much I identified with the protagonist. What kind of trauma had I gone through to make me want to show her this film?

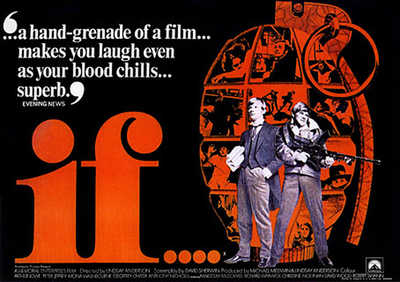

That movie was Lindsay Anderson's 1968 feature If.... – one of the most important films in the "Blow Up Your School" genre. (And yes, despite everything, she still married me.)

The film begins in late September, at the start of Michaelmas term, at a British public school (which is to say private, if you're not British) called simply College, though it was based on Cheltenham, where Anderson was sent before he won a scholarship at Wadham College, Oxford.

Even today, it's hard not to watch the first few scenes without an anxious pang in my chest: students noisily settling in to their new places, struggling to find themselves on the lists of names on bulletin boards, fighting to establish their position in the pecking order with both words and fists. We didn't have to move in trunks of belongings and provisions – St. Mike's wasn't a boarding school – but the chaos and the lists and the violence are all familiar.

After a while we meet Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell), a student in the lower sixth form who, along with his friends Wallace (Richard Warwick) and Knightly (David Wood), comprise the core of the school's rebel faction. Opposing them are the House Whips – four upper sixth form boys led by Rowntree (Robert Swann), who have eagerly put themselves in charge of discipline at College House thanks to the dithering leadership of the Housemaster, Mr. Kemp (Arthur Lowe).

There's a rundown clamminess inherent in both the buildings and the social hierarchy at College. The junior boys are known as Scum, and their study hall is called the Sweat Room. The most modern thing we see in the whole place is the new reflecting telescope brought from home by Peanuts (Philip Bagenal), the resident nerd in the senior class; apart from that there's nothing about the place that looks like it's been updated since the First World War.

College is a school with a great deal of tradition – five centuries old, we're told – but not a lot of money. It's a school by and for the children of the middle class, and its social hierarchy breaks down along the dozens of fine distinctions that subdivide this social class, and which only an Englishman would probably have the acuity to recognize. College is the sort of place where the struggle upwards begins in earnest for its students, from new money arrivistes, to old families struggling with inheritance taxes and divorce, to the children of the well-connected, boosting themselves up to the gentry with the aid of a knighthood.

This is embodied in the Headmaster (Peter Jeffrey), the sort of glib, polished man who delegates effortlessly and brags about making tradition harmonize with modernity, and of the school's "high standards in the television and entertainment worlds." He's very telegenic, but he does very little besides project a flattering image of College to parents, alumni and the media; beneath him, ages-old rituals of humiliation unfold without interruption.

Gavin Lambert was a classmate of Anderson's at Cheltenham, and would later write Mainly About Lindsay Anderson, a biography of the director. He describes Cheltenham as "a bit lower down the social ladder than Eton or Harrow, the most exclusive public schools for sons of aristocrats, plutocrats and diplomats, but had a strong military tradition and specialized in preparing sons of officers for one or other of the Army training colleges, Sandhurst and Woolwich." He recalled "the stone corridors that reeked of carbolic acid...the stark and uncomfortable chapel, and the dining room where we sat on long, worn benches like convicts in a prison movie."

What Cheltenham, College or any other school, public or private, real or fictional, shares is a relentless pressure to conform. Even the misfits, like Mick and the Rebels, need to their way into a group; loners are bullied mercilessly, like the sole, overweight Jewish senior student, or poor Biles, the odd man out in the junior class, hunted down by his classmates and hung upside down with his head in a toilet.

"Help the house and you'll be helped by the house," is the start of term message given to the students by their Housemaster. "Yet all this proved a valuable guide for the world to come," recalls Lambert of their time at Cheltenham.

"The mistrust of 'intellectuals' or anyone 'different' was a foretaste of middle class pressure to conform, just as unsavory food or persistent winter colds and chilblains signaled its belief in the moral value of discomfort."

Mick arrives at school with his face covered by a black scarf and hat, where his dormitory prefect Stephans (Guy Ross) remarks that "it's Guy Fawkes back again." He's grown an impressive moustache over the holidays; he brags to Wallace and Knightly that he spent it with a "bird" from the East End – an interlude that sounds suspiciously like slumming, and ended when she brought him around to meet her parents.

"God, you're ugly," Knightly tells him. "You look evil." It's obviously meant as a compliment.

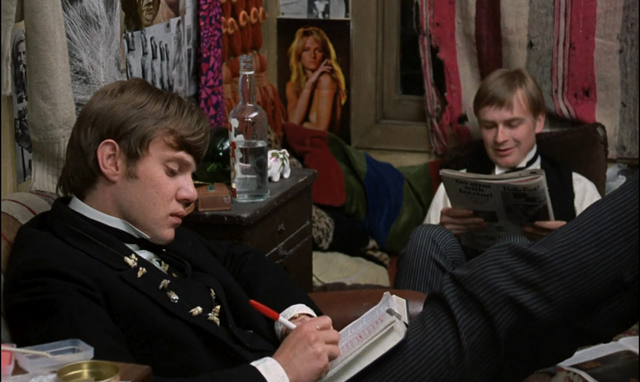

He shaves off the moustache but settles in to continue his rebellion against the Whips, their house and College in general. The Rebels decorate their dank shared study room with pictures cut from magazines – stark, grainy images of slums, bums and dirty children, and war reportage from Vietnam and the various other insurrections, rebellions and civil wars going on all over the world.

While his friends have gathered around him out of shared nonconformity, Mick clearly sets the tone for the Rebels – a morbid preoccupation with violence and death that they've harvested from world events and pop culture. Mick in particular is fond of issuing pronouncements like "violence and revolution are the only pure acts," slogans he's obviously picked up from political revolutionaries and the intellectuals who support them.

"The whole world will end very soon," he tells his friends. "Black, brittle bodies peeling into ash."

Amazingly, Lindsay Anderson managed to get permission to shoot most of the exteriors for If.... at Cheltenham, after sending them a "laundered" version of the screenplay he'd written with David Sherwin – a script that had begun as a story called "Crusaders" in 1960. Student rebellion was fermenting when they began filming, and broke out that summer with riots on U.S. campuses and in the streets of Paris. They gave the film a currency and shock value when it was rushed into release by Paramount in December, after Barbarella flopped on English screens.

But Anderson had never meant for it to be so topical. In his biography, Lambert notes that "Lindsay was determined to avoid any exploitation of current events, which is why the Cheltonians don't wear literally contemporary costumes or use contemporary student slang, why the 'revolutionary' photographs on the walls of Mick's study are generalized (no Che Guevara or Bobby Seale or Chicago Seven), why no one performs or listens to any contemporary popular music..."

So no bellbottoms or mod scarves or Jimi Hendrix or The Who on the soundtrack, though Lambert was wrong – there's a poster of Che on the wall of the junior Sweat Room, next to a portrait of the Apache rebel Geronimo. Obviously the younger Cheltonians are primed for more specific political agitation than their senior peers.

The only music we hear Mick play on his study record player is the "Sanctus" from the Missa Luba, a setting of the Latin mass in Congolese, recorded by Les Troubadours du Roi Baudouin in 1958 and released on the Philips label. Mick handles the record reverently, like a relic, and the music appears elsewhere on the soundtrack, even on a jukebox in a roadside café.

Filmgoers would have heard it four years earlier, on the soundtrack to Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew, and in the 1966 MGM film The Singing Nun, starring Debbie Reynolds. McDowell would be seen with the record again in A Clockwork Orange (1971), and The Clash would refer to it in "Car Jamming", on their album Combat Rock (1982). Mojo magazine stated in an article that the record was formative to the sound of Led Zeppelin.

In the light of the unwelcome gift of topicality that current events gave If...., it's a challenge to discern just what kind of revolution Anderson imagined Mick longed to begin. The Missa Luba imagines that it might be a spiritual one, or one that longed for a more primitive, essential life. As Mick implores his fellow rebels, "When do we live? That's what I want to know."

Anderson himself was a conundrum; a semi-closeted gay man with a propensity for falling in love with unavailable, straight and married men, he's described in a 2003 BBC television interview with his key collaborators on the film as a "bourgeois bohemian" (by the film's editor, David Gladwell), and by screenwriter Sherwin as a man who "read the Daily Telegraph and believed in capital punishment."

The movie's most scathing indictment of the senior Whips is their sexual hypocrisy. A junior boy, Bobby Philips (Rupert Webster), who's pressed into service as Rowntree's servant (one of the privileges of authority at College, often called "fagging" at real public schools), is openly lusted after by the other Whips, with the notable exception of Denson (Hugh Thomas), who dismissively scorns their indulgence in "adolescent homosexuality." In retaliation, Rowntree reassigns Philips as Denson's scum, knowing that the other whip is only barely in control of his own lust for Philips

This is contrasted with the romance that develops between Philips (who wants to move to California and become a lawyer) and Wallace, which begins with a slow motion scene where the junior watches the senior student show off with a gymnastics routine, just before Mick and Knightly burst in to start a mock fencing match that ends with Wallace cutting Mick's hand. He holds it up to show the red wound to his friends with amazement.

"Look – blood," he says. "Real blood."

All of this plays into Anderson's intense portraits of young people longing for something genuine and authentic, and their scorn of what they consider imposed, false and transitory – a "phase" that makes their feelings seem trivial. Lambert recalls what school authorities at Cheltenham called "unhealthy attachments" – what "Tarts" such as himself regarded as "playing forbidden games, like smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol. All that mattered was not to get caught."

"As for the senior Toughs, who were allergic to introspection, they knew it was just a 'phase' that 'normal' adolescents went through and grew out of. Later, in fact, most of them became husbands and fathers; and so, probably did most of their Tarts."

I don't recall any of this at St. Mike's, which wasn't a boarding school, and was located in the middle of a big city, not in rural isolation. Sexual predation, either by students or teachers, wasn't a feature of school life, though the school was rocked by a major scandal just a few years ago, with an unverifiable incident involving several athletes and – in at least one version of the story – a hockey stick, a sordid incident that was both inspired and amplified by teenagers on social media. In any case, a very different – and not coincidentally much better funded school than the one I attended, with tuition several times higher than when I was a student.

The Whips decide to focus their punishments on Mick and the Rebels, a "hard core" who, as they explain to the Housemaster, needs to be rooted out. It begins with cold showers, and escalates to canings – an arbitrary punishment that the Whips pronounce on the Rebels not for anything they've done, but because of their "attitude." Informed of the imminent beating, Mick replies "yes" when asked if he has anything to say:

"The thing I hate about you, Rowntree, is the way you give Coca Cola to your scum and your best teddy bear to Oxfam, and expect us to lick your frigid fingers, for the rest of your frigid life."

The beating – more than twice as long for Mick as for Wallace and Knightly – inspires the Rebels to a blood pact, and an even more extreme rebellion against the authorities, the severity of which Mick signals when he produces a handful of real bullets from a hiding place in the study.

At this point, the film has begun to detour into fantasy, which begins when Mick and Knightly go AWOL from campus and steal a motorcycle from a dealership in town. They stop at a roadside café and meet The Girl (Christine Noonan), who has no other name, and embodies everything missing from their lives at College.

Mick forces a kiss on her, for which he gets a slap, but she comes up behind him at the jukebox and fixes him with a stare. "Look at my eyes; I've eyes like a tiger. I like tigers." She snarls at him; he sniffs her, then they begin hissing and clawing at each other in the middle of the café. They fall into a heap on the floor, which cuts to the pair naked as they wrestle. (The nudity was McDowell's idea, timidly suggested to Anderson, who said he'd do it if Malcolm asked Noonan to agree. McDowell admitted that it wasn't a suggestion he made entirely at the service of the story.)

The stolen bike and the escape from campus have no apparent repercussions, which suggests that from this point on the film has departed from reality. Back at College the school is sent out on exercises; as part of their martial tradition, students are given surplus uniforms and Lee-Enfields and sent out for war games with the school chaplain as their general, in uniform and astride a horse.

The Rebels bunk off from their squadron and wander through the woods, then take up position overlooking a bivouac; they take out their live rounds and begin peppering the tea urn and truck windows, sending everyone but the Chaplain running for cover. He confronts the Rebels, but Mick emerges from cover and walks toward him, taking aim and firing point blank, then lunging in with his bayonet as the vicar cowers on the ground.

"I take this seriously," the Headmaster scolds them in his study. "Quite seriously indeed." What follows is a bloviating lecture about his sympathy for rebellion, "hair rebels" and duty; he opens a drawer in the wall containing the Chaplain, who sits up and accepts their apologies before shaking their hands. The Headmaster shuts the drawer again, then tells the Rebels he has an appropriate punishment in mind.

The Rebels are set to clearing out a storage space beneath the lecture hall; Wallace and Bobby Philips carry a huge taxidermy crocodile out to a pyre to be burned, but then the boys discover a locked cupboard full of medical specimens in jars. Mick takes out a foetus, but The Girl emerges from the shadows and places it back on the shelf, firmly closing the cupboard. Then they find a hidden stash of weapons – a forgotten armoury of Bren guns, mortars and ammunition.

Even in spite of what came before, the final scene of If.... will always give it lasting infamy. Anderson and Sherwin have always acknowledged the debt their film owed to Jean Vigo's 1933 surrealist short Zero de Conduite, about a rebellion in a French boys' school. The structure and story are remarkably alike, right down to the rooftop attack at the end, but Vigo's film is about small boys, and has a corresponding antic lightness that If.... forgoes.

Speech Day brings together the whole school, including parents and alumni – three of whom parade into the lecture hall in armour – an unspecified member of the royal family and the keynote speaker, a General Denson, presumably a member of the whip's family. He's barely begun rolling out a speech loaded with what an audience in 1968 would recognize as Tory platitudes when smoke starts pouring from beneath the stage and the crowd rushes for the doors.

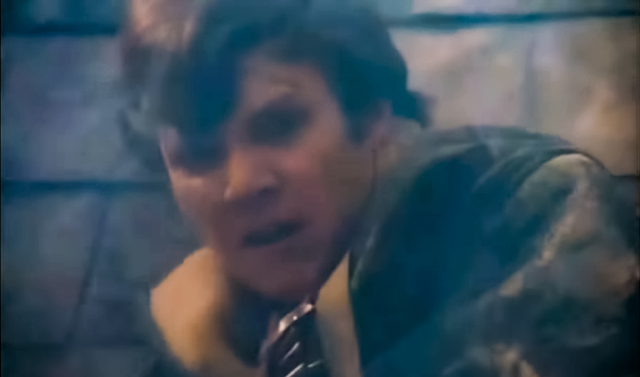

Outside, they're met by mortars and gunfire from the roof above the quadrangle, where the Rebels, joined by Bobby Philips and The Girl, are dressed as paramilitaries in camo jackets and berets. The Headmaster calls for a truce and pleads with the rooftop revolutionaries – "Boys! Boys! I understand you!" – and gets shot between the eyes by The Girl.

The school and its guests break open the armoury and begin returning fire; one hilarious shot features a portly matron, firing a Sten gun and bellowing "Bastards! Bastards!" A counterattack begins, the quad filling with students, guests, alumni and clergy firing up at the roof, where Mick and the Rebels are cornered, outnumbered; the last shot is a zoom in on Mick, his expression desperate behind the smoke from his gun.

The scene was shocking in 1968; it was meant to shock, but it was understood as a provocation. Gavin Lambert details the ambiguity of the ending and Mick's fate: "Will he be killed, arrested and sent to jail, or escape? Can any revolution succeed without violence? Or if these rebels succeed against all odds, will they create a new Establishment, as repressive as the one they overthrew?" And above all, did the rebellion even happen, or was it all Mick's fantasy?

Whether you were appalled or elated by the spirit of revolution in the air, it didn't really matter. At least one old Cheltonian joined the chorus of fans of the film and its revolutionary message; Australian novelist and 1973 Nobel laureate Patrick White said that "the buildings of my old school added to the horror of the story; the revolution part of it seems to have been simmering in me all these years, and I was on the roof with the other sten-gunners."

On the other hand you had the film's cinematographer, Miroslav Ondříček, an eyewitness to the recent violent Soviet suppression of Prague Spring. Recalling the filming for the BBC in 2003, he said he didn't see a revolution happening in Britain; quite the opposite – he loved being in England considering the alternative at home in Czechoslovakia.

It still has the power to shock today, in no small part thanks to our horror of school shootings, which seem to the public imagination to have become more frequent. In any case, should a school shooting have happened in the week previous to publishing this column, it doubtless would have been pulled as a matter of prudence and probity.

Mick Travis would go on to survive, at least in Anderson's filmography: McDowell would play him again in O Lucky Man! (1973), a wild picaresque fantasy that sent him up and down Britain and its social structure on a series of surreal adventures, and once more in Britannia Hospital (1982), a black comedy that was meant as an allegory for Thatcher's Britain, and the weakest film of the trilogy. Anderson would make two more features – a concert film about the pop group Wham! touring China, and The Whales of August (1987), a gentle drama starring Bette Davis and Lillian Gish that resembles nothing else in his career. He would die of a heart attack in 1994.

If.... would launch Malcolm McDowell's career; Stanley Kubrick saw it five times and cast McDowell in A Clockwork Orange as Alex, a character that simply added an extra layer of sociopathy to Mick. The character's taunting smirk would be a part of McDowell's onscreen persona for decades to come, from Harry Flashman to Caligula to Rupert Murdoch.

Nothing much has changed for high schools. British public schools still fill out the ranks of that country's establishment, while American ones are increasingly funded with public money disproportionate to their results. Pop culture still depicts them, in my friend Kathy's words, as "prison camp with prom," though lockdown gave home schooling a new legitimacy that Heathers and Mean Girls could never inspire.

In the meantime, September is finally just a month that makes me sad, as the inevitability of winter is once again difficult to ignore. And after four decades, it's finally possible to forget five years of boys' school.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.