Her death, when it came, happened late on a weekday afternoon, when nobody seemed to be expecting it. You got the sense that even the news anchors who'd had to change into black clothes halfway through their work day were struggling to adapt to the script that had been handed to them, even if it had been written and rehearsed regularly for years or decades. But it was always going to happen this way, at the end of the longest reign in modern history.

The period of mourning leading to her funeral will showcase considerable pomp and ritual, but it will also give us a chance to once again experience something much stranger: millions of people, many not even subjects of the late monarch, uniting in shows of public grief that they might not summon up for friends or even family, for a person whose lifestyle and circumstances they could never hope to understand – and might adamantly reject if it were offered to them.

This unprecedented sense of familiarity – probably unique in the history of monarchy – has a lot to do with how news and documentary cameras intruded into the life of the late Queen and her family. It was a barrier broken with their consent by Royal Family, the 1969 BBC documentary commissioned by the Queen to celebrate her son's investiture as Prince of Wales, and later banned from the airwaves by her. This opened the floodgates for depictions of the Queen on film and television, albeit initially just in comedies and cartoons.

The first onscreen portrayal of the Queen was by a man in drag – Steven Walden in the 1971 X-rated comic short film Tricia's Wedding. She was portrayed more often than anyone else by British actress and lookalike Jeannette Charles, who played cameos as the Queen for decades in everything from Secrets of a Superstud and Queen Kong (both 1976) and Eric Idle's Beatles parody All You Need Is Cash (1978) to National Lampoon's European Vacation (1985), The Naked Gun (1988) and Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002).

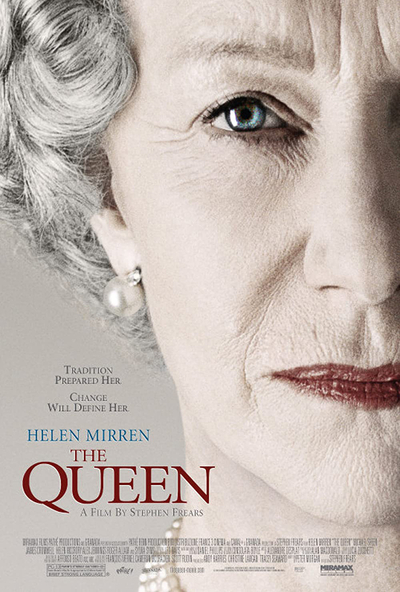

It wasn't until 2006 when a serious actress played the Queen in a serious film where she was the main character – Stephen Frears' The Queen, with Helen Mirren as the monarch, beset by the greatest crisis to trouble her reign, during one infamous week in the summer of 1997. The film was written by Peter Morgan, a playwright who would go on to create The Crown, the hit Netflix miniseries that has populated and defined the public image of life in the royal family of Elizabeth Regina, likely for generations.

The film begins with the Queen in full ceremonial regalia, posing for a portrait painted by "Mr. Crawford," an artist played by Bahamian-born British actor Earl Cameron and meant to stand in for countless other traditional royal portraitists from Pietro Annigoni to Henry Ward to Andrew Festing. He's an older man, and not terribly impressed by news of Tony Blair and New Labour's unfolding election victory playing on the nearby television; he tells the Queen that he was first in line at the polls, but didn't vote for him.

"You're not a modernizer then?" the Queen asks him.

"Certainly not," Crawford replies. "We're in danger of losing too much that is good about this country as it is."

Tradition continues in the form of the Royals' regular summer migration to Balmoral, their 40,000 acre estate in the Scottish highlands, while Tony Blair (Michael Sheen) and his new government set about their agenda of modernization. The glimpses we see of life in the royal household duplicate the ones the public first saw in Royal Family – a startlingly banal life, lived while dressed with the maximum formality possible (men always wear ties) in vast, lavishly furnished rooms, where the royals spend most of their time reading, answering correspondence or watching TV while a huge staff goes about their business in the background.

The Blairs, by contrast, live in a cluttered house that looks like student digs – bookshelves full of paperbacks, walls covered in random artwork, some of it by children. (10 Downing Street is apparently unready for habitation. Armed security stand in a doorway, a foot or two away from the family at their messy breakfast table.) Tony's wife Cherie (the late Helen McCrory) is an undisguised republican whose hostility to the monarchy is reinforced by the awkward, chilly first audience her husband has with the Queen upon taking office.

"Have they shown you how to start a nuclear war yet, Mr. Blair?" the Queen wryly asks her new prime minister – the tenth so far she's invited to form a government; her reign would ultimately contain fifteen.

The crisis, when it comes, starts in a tunnel in Paris; Frears cuts from his re-enactment of the car chase that killed Diana Spencer, Dodi Fayed and their driver, Henri Paul, to brief flashes of TV coverage of Diana throughout her public life. The news reaches Blair and the royals at about the same time, but Frears' film has the Queen and her husband Philip (James Cromwell) take in the breaking news passively, on television, like nearly everyone else, while Blair and his staff are at work, receiving regular updates, and preparing reactions in the hope of being able to shape the story before it shapes them.

Leading this effort is Alastair Campbell (Mark Bazeley), strategist for New Labour's campaign, now the prime minister's right hand man and master of the art of spin. Alongside Peter Mandelson, Campbell was one of the "dark lords" of Blair's government, and would be the inspiration for Peter Capaldi's profane, abusive, cynical government fixer Malcolm Tucker in the BBC miniseries The Thick of It. Bazeley plays him as a smug, sarcastic political player, even more outspoken than Cherie Blair in his hostility to the monarchy; before Diana's body is cold he wonders aloud if the royals had "greased the brakes" on her car.

Divisions within the royal family start to appear while that body cools, with Charles, the Prince of Wales (Alex Jennings, who would later play the Duke of Windsor in the first two seasons of The Crown) bristling as his mother and her advisers insist on treating his ex-wife's death as "private" and "a family affair". They pressure him to avoid lavish expenditure and try to get a commercial flight to Paris, and ignore a helpful suggestion by the Queen Mother (Sylvia Sims) that he use the royal plane kept on standby to collect her body on the occasion of her own demise to bring home Diana.

Events begin to move quickly. Diana's brother Charles Spencer gives an emotional press statement blaming both the media and the royal family for his sister's death, and when it becomes obvious that the tragedy has unleashed a wellspring of public sympathy for Diana, plans are changed from a private service to a state funeral, in flagrant violation of precedent. In the meantime Campbell is seen jotting down notes for a speech that Blair would deliver the day after Diana's death, referring to her as the "people's princess", a phrase that would resonate and legitimize public reaction as it hypertrophied in the week – and subsequent years – that followed, for which Campbell makes sure he garners credit.

"You owe me," he tells his boss.

Back at Balmoral, the family is intent on treating Diana's death as a private tragedy, and the Queen's prescription for her grieving grandsons is to send them out every day in a stalking party, hunting for a 14 point stag that's been spotted on the estate. Her only concession to optics is worrying how badly it would look if one of the boys were photographed carrying a gun. Her mother amuses herself by speculating that any press photographer discovered on the estate might be "the first kill of the day."

In the meantime the Queen's private secretary Robin Janvrin (Roger Allam) sits watching Blair's speech on the TV in his office with an audience of mostly female staff. He declares that it was "a bit over the top, don't you think?" before looking around and realizing that the women are sobbing.

Frears and Morgan's re-telling of that week in late summer of 1997 is, on the surface, a battle between precedent and emotion. There were, of course, protocols in place for the death of every royal. (In The Queen, the Queen Mum is slightly put out when the playbook for her own death – codenamed Tay Bridge – is adapted to Diana's, mostly because it's the one that was most recently rehearsed.) But Diana wasn't just any royal and, technically, had been demoted at the time of her death to just another aristocrat with a colourful history in the tabloids.

There was a lot of improvisation going on in the hours and days after Diana's death, and enormous importance given, for example, to the flying of the royal standard, whether at half or full mast – a debate that took place despite literally centuries of precedent, with optics almost inevitably winning over tradition. Mark, the proprietor of this site, recalled in a recent column on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of that week that the BBC kicked it off by playing the national anthem after announcing her death – despite Diana no longer being a member of the royal family.

"In the event, the Beeb proved nimbler at adaptation than the Palace," Mark wrote. "As for the anthem, on the streets of London the mob were in no mood to have a God who'd failed to save the Princess save the Queen, not from their mounting rage. It was a week of coerced pseudo-empathy, in which the people demanded Her Majesty emerge from what they called her 'ice palace' and, as I put it back then, come out and feel their pain - or they'd come in and give her some of her own to feel..."

Awareness of a change in public attitude was slow to penetrate the royal household. Blair and his government were the first to sense it, but they were primed to do just that, especially just after a general election. Charles was also keenly aware of it, partly because he and his sons were the only royals with a genuine emotional reaction to Diana's death, but also because, after living his life waiting in the wings, he has always been eager to appear the modernizer in the palace, and he quickly seeks out Blair as an ally.

Janvrin, the queen's private secretary, notices it next, and begins working stealthily to moderate communications between the palace and the government. On the surface it would seem that Morgan and Frears are keen to depict these men as being in possession of an emotional intelligence that the majority of the Windsors can't access, but the sudden and fervent rise in public antipathy to the royals is a threat to their jobs – Charles' putative future one, Janvrin's current one, and a potential impediment to the agenda of the one that Blair has only just won.

It's also worth noting that the media – fingered by Charles Spencer alongside the royals as the villains who killed Diana – are more than eager to stoke the chorus of condemnation when it's obvious that it will take the heat off them.

At this point it has to be understood that the court drama Morgan has done so much to visualize over the course of The Queen and The Crown is still just purest speculation. The royals themselves have strove mightily to make sure that whatever brief scenes from life at the various palaces we've glimpsed since Royal Family are as anodyne and tedious as possible. And for every courtier and insider who tells all, there are hundreds happily sworn to silence, loyal to the public image of duty above all else, performed in a setting of painstakingly unspectacular luxury.

But Morgan's genius is evoking indelible scenes out of that barren ground. Like the one, early in the first season of The Crown, where young Elizabeth (Claire Foy) has a sexy safari idyll with her husband cut short by the death of her beloved father, George VI. She flies home on the royal plane, changing into mourning black on the way, and struggles to maintain her composure after visiting her father's body lying in uniform on the bed where he died, the embalming instruments and machinery still in the room.

She emerges from his bedroom the Queen, accepts curtsies from her mother and sister in a daze, and descends the stairs to meet her grandmother, Mary of Teck, herself about to transition from Queen Mother to Dowager Queen. The gaunt old woman, a year away from her own death and a living relic of the Victorian and Edwardian heyday of the empire, slowly approaches, her head shrouded in a black veil. She curtsies with eerie grace to her granddaughter, now her Queen, her eyes never leaving the young woman's face. It's a chilling scene, evocative of a horror movie more than a royal melodrama, underlined by ominous music and the growing look of terror on Claire Foy's face as she realizes what has happened to her, and the agency she has lost forever.

That this scene plays out to the backdrop of Winston Churchill (John Lithgow) doing an end run around Anthony Eden (Jeremy Northam) for the leadership of the Tories with a barnstorming oration on the King's death and the Queen's succession is proof of what excellent writing looks like.

Morgan conjures up another evocative scene in The Queen, when Mirren's Elizabeth takes out one of her antique Land Rovers to drive across the wilderness of Balmoral and find the hunting party. She tries to ford a stream and breaks the front drive shaft on the rocks, then settles in on the bank to wait for someone to fetch her. Alone in a stark, magnificent highland valley, she starts sobbing, but stops when she notices that the stag her family is pursuing is standing on a rise above the stream, watching her.

In The Crown, Morgan does little to dispel ages-old criticism that the Queen is, at heart, a simple, not particularly intelligent "country woman." It's a charge she hears often, whether the character is played by Foy or Olivia Colman, and will likely follow Imelda Staunton as she takes over the role for the final two seasons. What no one denies is that the Queen was most relaxed and content away from London, and busy either improving the bloodline of her horses or enduring the changeable weather at Balmoral.

Mirren's Elizabeth is awestruck at the sight of the huge stag, whispering "Oh, you beauty!" to herself, and tries to scare away the animal when she hears gunshots in the distance. Later, as pressure from Blair, her son and others finally moves her to bring the royal household back to London, she hears that the stag escaped the estate, but ended up being bagged on a neighbouring one, shot – as Philip notes with unconcealed disgust – by a "commercial guest," an "investment banker from London."

Elizabeth jumps in a Land Rover and drives to the neighbouring estate, where the head ghillie shows her the body of the animal, hanging by its feet in an outbuilding abattoir, head removed and set aside to be turned into a trophy. She notices that it has a wound in the side of its head; the ghillie explains that the banker was a poor shot and only wounded the stag, who had to be tracked and killed by guides.

It doesn't take a genius to understand why Elizabeth would see herself – not individually but as a representative of an institution – in that stag. There is certainly a precedent for royals being hunted down, their heads displayed as trophies. And if you embody an institution that once held incredible temporal power, you might identify as magnificent, pitiful and endangered all at the same time, and definitely threatened by an aspirant commoner with poor aim. (Perhaps not coincidentally, for much of the movie her son Charles is in mortal fear of an assassin's bullet.)

Back in London, the Queen's story merges again with real history; Frears cuts plenty of archival footage into his movie, and when the royal motorcade makes its way back to the palace, we hear real colour commentary on the soundtrack – former prime minister Margaret Thatcher, and a voice I swear is that of (future and now former PM) Boris Johnson, then a columnist at the Daily Telegraph and the Spectator. It's a cinematic trick that helps make stories like The Queen seem more like a document than speculation.

As the week unfolds, Sheen's Blair becomes more and more sympathetic with the Queen, even as he forces her to bend to the will of the people, quite against her inclination and instinct. It's a change that his wife acidly tells him is part of his mother complex, and in any case "at the end of the day all Labour prime ministers go gaga for the Queen." It leads to him blowing up at Campbell's cynicism, shouting at his spin master that "when you get it wrong you really get it wrong!"

The film ends two months later, and another audience between the Queen and her chief minister, the two of them obviously on better terms, though Blair is still careful when he brings up the events of that terrible week. He tries to congratulate her, praising among other things her humility, though Elizabeth is quick to tell him that "You're confusing humility with humiliation."

She's still shaken by the fickle, overwrought public reaction to Diana's death and the royal response, and how one in four of her subjects claimed they were now against the monarchy – a surge in republican sentiment nearly unprecedented in Britain. The prime minister tries to tell her that it could never happen again, but the Queen is not so sure, and warns him to be prepared not for if but when it happens to him – "quite suddenly and without warning."

Somewhere between The Queen and The Crown Morgan took a harsher line on Prince Charles – now King Charles III. He's the only member of the royals to understand the public's reaction to his wife and her death, but he irritates his parents with his neediness and hunger for a larger role. The Queen drily tells her husband that their son "was good enough to share with me his thoughts on motherhood."

By the time Josh O'Connor took over the role for seasons three and four of The Crown, though, Charles had evolved from a bullied, unhappy boy to a whining, entitled brat who exasperates his mother with his solipsism and self-pity, and nearly destroys his pretty young wife with the ongoing affair with Camilla Bowles and his rage when she feels betrayed at the infidelity. There's no way to know how Morgan's Charles might evolve when Dominic West takes over the role for the final two seasons, but the last two definitely soured public perception of the Prince of Wales on the eve of his accession.

There's a rumour that Netflix will postpone November's planned debut of season five of The Crown out of respect for the Queen's death – though it's hard to imagine the streamer letting it sit too long on the shelf in the shadow of a mountain of free publicity. Filming on season six has also apparently been suspended, though this might be a fortuitous chance to rewrite the series finale in light of real life providing such a natural conclusion.

The upcoming season would see Morgan revisit the events of The Queen, along with 1992's "annus horribilus." If season six follows the story to Elizabeth's death, it will have to visit Prince Andrew's unsavory public disgrace, the unedifying Sussex soap opera and the death of Prince Philip on the way.

As hard as it is to believe right now, it was generally assumed that the Queen would still be alive when the finale of The Crown aired. More an institution than a person, it was always assumed that she would be there. Her sudden exit is a reminder that nothing is permanent, and as Helen Mirren's Elizabeth warns Tony Blair, respect and longevity won't prevent any person or institution – or combination of the two – from disappearing, "quite suddenly and without warning."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.