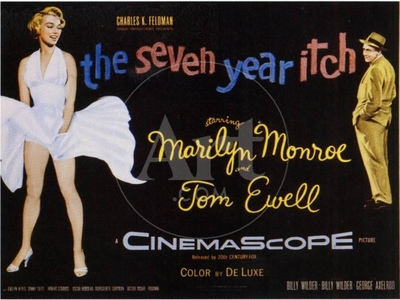

The 1955 film The Seven Year Itch is so central to the myth of Marilyn Monroe that its director, Billy Wilder – still among the most celebrated of Hollywood's "auteurs" – is often relegated to a footnote in its creation. Wilder might not have cared – while he was fond of disparaging it as one of the slightest pictures in his filmography, it was still a huge hit, so he made enough money from the film to feed his love of bespoke clothes, fine food, travel to Europe and collecting art.

Monroe, at the peak of her fame, was already notoriously difficult on set, habitually late and unable to remember lines, but Wilder was so certain that she would deliver to his story all those rare qualities that made her a star that he overlooked this and even worked with her again on Some Like It Hot four years later – a picture considered far more essentially a Wilder film.

Still, the acerbic Wilder couldn't resist venting about Monroe to the press after the experience, saying that he might not work with Marilyn again in the States, but if they made the film in Paris he might be able to take painting lessons while waiting for her. He also described her as having "breasts like granite and a brain like Swiss cheese," adding that he hoped that she wouldn't get "straightened out" and cured of what made her such a unique star. "The charm of her is two left feet," Wilder said, by way of a compliment. "Otherwise she may become a slightly inferior Eva Marie Saint."

This was too much for Monroe, and Matty Malneck, composer of the score for Some Like It Hot, tried to effect a détente between the two by placing a call to Wilder and putting Monroe on the line. Wilder's charming wife Audrey answered the phone, and told Marilyn that Billy wasn't home.

"Well, when you see him, will you give him a message for me?" Monroe said. "Tell him to go fuck himself. And my warmest personal regards to you."

When I first encountered The Seven Year Itch on television as a teenager, I didn't see it as a Wilder or a Monroe picture as much as a film about summer in the city, so assiduously do Wilder and scriptwriter George Axelrod set the scene, painting a humid, sweaty picture of Manhattan in July and August, where men once stayed behind to work while their wives and children are sent off to the beaches and mountains of New England and upstate.

After a satirical prologue that imagines this as a tradition going back to the Native Americans who once owned the island, the film introduces us to Richard Sherman (Tom Ewell), a middle-aged man in a summer-weight suit seeing his wife (Evelyn Keyes) and spoiled, tow-headed son off at Penn Station. The glimpse we get of this midcentury American family isn't flattering – his wife persistently scolds him about his health and his son is fantastically annoying, stupidly firing his toy ray gun at a porter while dressed in a Captain Video outfit – but the brief pan through old Penn Station is heartbreaking, especially if you know that it would be demolished in less than a decade and replaced by a rat's nest of tunnels.

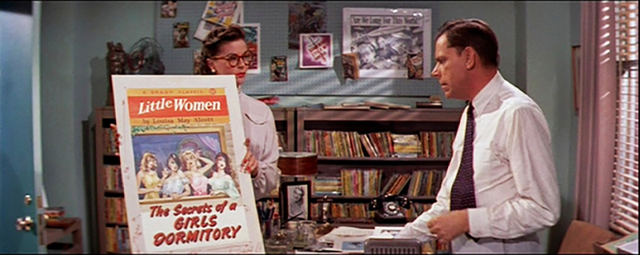

Sherman is an executive at a publishing company that specializes in re-packaging classic literature as potboiler dime store novels; we see him overseeing the cover art for a pulp edition of Little Women, using a magic marker to tell the cover artist to give the little women on the cover more cleavage. On the way home he decides to stay away from the bars and taverns and pay a virtuous and penitential visit to a vegetarian restaurant, where his soybean-heavy meal gives him gas.

These scenes are the most definitively Wilder in the picture, with their relentless – perhaps a bit overplayed – satire of American vulgarity and earnestness. The hatchet-faced waitress launches into a rant when she informs Sherman that there's no tipping, but any gratuities will go to support a nudist camp.

"Clothes are the enemy," she declaims. "Without clothes there would be no sickness, no war. I ask you sir, could you imagine two giant armies on the battlefield with no uniforms, completely nude? There'd be no way of telling friend from foe – all brothers together!"

There are a lot of things about The Seven Year Itch that make it a period piece, but Wilder's ritual satires of American subcultures on their obnoxious and wooly-headed high horses would offer him so many overripe targets today. It's worth noting that this Jewish refugee, who devoted his time before the war working to rescue Europeans from the Nazis, still managed to avoid being collected up in the post-war red scare that labeled so many of his peers as fellow travelers and "premature anti-Fascists." Skeptical and never idealistic, Wilder wasn't motivated by politics as much as aversions.

Sherman makes his way home – a typical Manhattan townhouse, divided up by the landlord and painted black with white shutters, a classic "update" at the time; later owners will curse him when they have to strip the paint to return it to its period correct look while turning it back into a single family home that will sell for millions of dollars.

He explains to us that there are three apartments. The Kaufmans upstairs collect African art and refuse to get air conditioning; they're away in Europe for the summer. (They'd have a "Hate Has No Home Here" sign in their window and a TV tuned to Rachel Maddow if the film was made today.) The top floor is rented by two guys, both interior designers – Sherman says this with a shrug that doesn't do much to let us know if he's unaware they're a couple, or whether he knows and just doesn't care.

He briefly glories in the empty apartment before the resentments surface again; against his wife for her many prohibitions before she left (no drinking, no smoking) and his son for leaving his junk everywhere, like the roller skate that gives Ewell a big pratfall when he steps on it. He's trying to act as if the summer along will be as much a vacation for him as it is for his family, but his anxiety and frustration are just below the surface. It begins to boil over when he discovers that the Kaufmans have sublet their flat to a gorgeous blonde, who buzzes his apartment when she forgets her keys, on her way home after buying a table fan.

Enter Marilyn Monroe.

Wilder was between steady screenwriting partners when he made The Seven Year Itch. His partnership with Charles Brackett, which had yielded gems such as The Major and the Minor, The Lost Weekend and A Foreign Affair, had ended five years earlier with Sunset Boulevard. It was a fruitful creative partnership but the two men were simply too different, and Brackett in particular was scandalized by Wilder's constant affairs.

Wilder would begin working with I.A.L "Izzy" Diamond two years later on Love in the Afternoon, and go on to co-write Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, One, Two, Three, Irma la Douce, Kiss Me, Stupid, The Fortune Cookie, Avanti! and The Front Page with him before ending their collaboration with the unfortunate Fedora in 1978. In the meantime, Wilder was running through multiple screenwriters looking for another partnership, and took on Axelrod when agent and producer Charles Feldman bought the rights for his play – widely considered unfilmable as long as the Hays Code was in force – as a vehicle for his biggest client, Marilyn Monroe.

In Sabrina, Wilder's previous film, Humphrey Bogart's Linus Larrabee asks his secretary to book two tickets to The Seven Year Itch as part of his big date with Audrey Hepburn's Sabrina. George Axelrod's play was still a big hit on Broadway when Wilder signed on with Feldman to direct, with Axelrod signing a contract to work on the screenplay with the proviso that Feldman and 20th Century Fox would wait until the Broadway run of his play was over before releasing the picture.

Ewell starred in the play, which was set entirely in the Shermans' apartment in Gramercy Park. The part of The Girl – she has no other name in either the play or movie – was originally played by Vanessa Brown, an actress who had parts in films like The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and The Bad and the Beautiful, and as Jane opposite Lex Barker's Tarzan in Tarzan and the Slave Girl.

Neither Brown nor Sally Forrest, her replacement in the Broadway production, was a blonde bombshell, but more the sort of good-looking young woman – the prettiest girl in some small town – who'd make their way to New York City looking for work in magazines or television. (As a footnote, Gena Rowlands would have a small part in the Broadway production, playing Elaine, Sherman's wife's best friend and bridesmaid, who Sherman imagines having a torrid affair with in the film, a fantasy sequence parodying From Here to Eternity's love scene in the surf.)

Ewell was up against Walter Matthau and – hard to believe but it's true – Gary Cooper for Sherman in the movie version, and Matthau even did a screen test, but Wilder saw that Ewell had just the right everyman quality required for a character who has to stand in for the average man in the audience, delivering much of the film's spoken dialogue to him in a running solo monologue.

Originally Wilder had planned to direct versions of the film in three different languages, with Fernandel playing Sherman for French audiences, and Cantinflas in a Spanish release. Later he dropped the Spanish version for a German one, but I have no idea who would have played Sherman in this one, and in any case the whole idea of multiple versions was dropped in the end.

Casting Monroe as The Girl sends the film version of the story to a whole new place, and makes the whole concept of "The Girl" more iconic and even profound than merely just a girl – any pretty girl, crossing the path of a man ripe for temptation. The fact that this is a story about infidelity was the reason it was dropped by several other potential producers like Jack Warner, Nunnally Johnson and even millionaire Huntington Hartford; a comedy about adultery would never get their approval, and even if any depiction of intimacy between Sherman and The Girl or any of his fantasy seduction was eliminated, "the subject material of adultery would still be the springboard of all comedy."

This would have been a red flag to the bull that was Billy Wilder, who had spent his career gleefully baiting the strictures of the Code. He managed to pull it off, convincing the Production Code Administration that, since no adulterous sexual acts were depicted in the script, there was no adultery in the film. It wasn't just Wilder who was not-so-secretly undermining the Code; Hollywood in the age of the independent producer was boldly colluding to poke holes in official self-censorship, and by the latter half of the '50s it seemed like the Production Code Administration had become complicit in what amounted to a slow suicide. In any case, by the time Wilder made Some Like It Hot in 1959, he was able to ride roughshod over taboos that would have been roadblocks just a few years earlier.

Wilder and Axelrod's script makes it plain that every man in Manhattan, from Sherman's boss at the publishing house to Kruhulik, his building's oafish, leering super (Robert Strauss, returning to Wilder's set after Stalag 17, and familiar to TV audiences from his roles on The Beverly Hillbillies, The Monkees, Bonanza and Bewitched) is off the leash and looking for action while their wives and families are away.

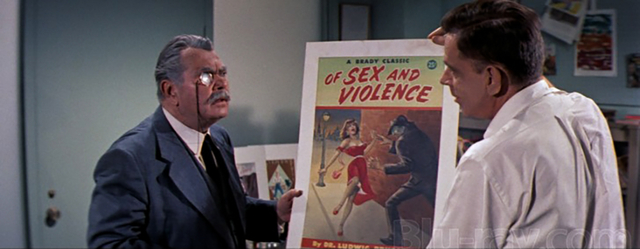

The film even grounds this in a pseudo-scientific theory proposed by Dr. Brubaker (Oscar Homolka), a psychologist whose academic tome on cyclical infidelity in males is being repackaged by Sherman's publishing house as the luridly-titled "Of Sex and Violence." Sherman is trying manfully to resist temptation despite his urges and a vivid fantasy life, so it follows that it would require not any girl but The Girl to overcome his (admittedly feeble) resistance.

Of all of Monroe's roles, The Girl, alongside Sugar Kane in Some Like It Hot, might embody her public persona more perfectly and completely than anyone else she played. The mixture of unalloyed sexuality and a sweetly naïve vulnerability – she refers to nearly everything as either "drastic" or "delicate" – was what made her such a compelling fantasy figure for the decade-plus when she dominated pop culture and the box office. Wilder's film gets to the heart of this appeal with a fantasy sequence where Sherman imagines seducing The Girl while he plays Rachmaninoff on the piano, while in real life she's reduced to shivers and goose pimples playing four-handed "Chopsticks."

While apparently personally immune to Monroe's appeal, Wilder still understood just what she embodied at the time, which probably explains why he signed up not once but twice to deal with the personal turmoil and unprofessional baggage that she brought with her to the set. It's also interesting to contrast The Girl with Evelyn Keyes, the actress playing Helen Sherman.

Keyes' reputation is based on her role as Scarlett O'Hara's sister in Gone With The Wind, and with a series of parts in b-noirs like Johnny O'Clock, The Killer That Stalked New York, The Prowler, Iron Man and 99 River Street. The oft-married Keyes (her husbands included Charles Vidor, John Huston and Artie Shaw) had the kind of torrid personal life that rivals and even surpasses Monroe's, including an abortion she'd later regret before filming Gone With The Wind, and affairs with Michael Todd, Glenn Ford, Sterling Hayden, Dick Powell, Anthony Quinn, David Niven and Kirk Douglas, detailed in her racy 1977 autobiography Scarlett O'Hara's Younger Sister: My Lively Live In and Out of Hollywood.

In Sherman's fantasies, Helen scolds her husband for his vivid imagination, belittling his image of himself as a potential sexual powerhouse, but she returns in them later, rolling around in a hayride wagon with Tom MacKenzie (Sonny Tufts), a handsome and conceited writer friend vacationing nearby in Maine, and gunning Sherman down in cold blood when she discovers his infidelity.

Wilder frequently remarked that America in the '50s was in the throes of a fascination with bosoms, with Monroe at the centre; Keyes on the other hand was a onetime pinup from the gam-obsessed '40s. Keyes herself wrote that "I have often wondered what my life would have been like if I had needed a size thirty-eight bra instead of a modest thirty-four."

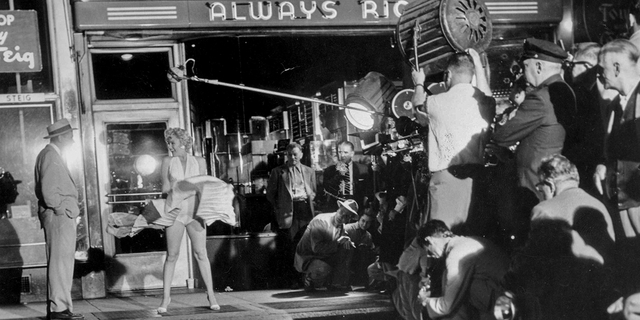

Wilder would discover just how out of control the Marilyn Monroe phenomenon was when they tried to film the most famous scene in the film on location on Lexington Avenue, where Ewell and The Girl leave a movie theatre and stand on a subway grate that blows up Monroe's pleated white dress whenever a train passes. Filming attracted thousands of onlookers, with film crew taking bribes to allow spectators to stand underneath the grate to look up Monroe's skirt, while Marilyn's husband Joe DiMaggio stood seething on the sidelines watching as his wife was being ogled.

According to the Monroe myth, this spectacle ended their marriage, and in any case Wilder had to film it again at the studio in L.A. when it was obvious that crowd noise had ruined the takes. It's a brief scene, and you could argue that the film wouldn't suffer it had been left on the cutting room floor, but the publicity generated by the New York shoot was a bonanza for the publicists at Fox, and the studio would end up breaking their agreement with Axelrod to open the film while his play was still running. A massive blow-up of Monroe with her skirts flying would adorn the marquee of Loew's State Theatre on Broadway, and it became the most famous image of the actress even before her early death.

Near the end of the film, when Tom MacKenzie pays a morning visit on Sherman, he's convinced his friend must be drunk as he rants about an affair with his wife, and the girl in his kitchen. What girl, MacKenzie asks, accusing his friend of being delirious. Any girl, Sherman replies – "Maybe she's Marilyn Monroe."

This is where it's possible to imagine The Girl as a figment of Sherman's fertile imagination, a manifestation of his guilt in the shape of the most desirable woman in the world at that moment. Except for a single scene with Kruhulik, nobody else actually sees Sherman with The Girl. Wilder complained later that he considered the film a failure because he had to cut a single scene that hinted that Sherman and The Girl had actually shared a bed, and that if he'd been able to make it at any point later in his career, he would have had them consummate their affair.

I disagree with Wilder. I think the unconsummated flirtation – more part of Sherman's take on his time with The Girl than her own understanding of the situation; she casually admits that people throw themselves at her all the time – is what makes The Seven Year Itch such a great film about guilt, as a punishment disconnected from any actual act. But obviously Wilder, the habitual, casual philanderer, wouldn't have much sympathy with what Jimmy Carter later referred to as committing "adultery in his heart."

Ewell, who had stumbled along in Hollywood with small roles in films like Adam's Rib, was suddenly a star after The Seven Year Itch, playing put-upon middle-aged males in films like The Lieutenant Wore Skirts, The Great American Pastime and The Girl Can't Help It the year after the film was released. Keyes would effectively retire from movies after The Seven Year Itch, while Wilder's next project was The Spirit of St. Louis, a biopic about Charles Lindbergh starring Jimmy Stewart, and a film remembered – it at all – as even less a part of the Wilder canon.

For Marilyn, however, it would be all downhill after The Seven Year Itch, even though it didn't seem obvious at the time – to her or anyone else. Teaming up with Wilder again would help sustain the myth, even as her reputation for being difficult on set knitted itself into that public image.

There would be an unfortunate – some would even say fatal – involvement with the Kennedys, and one film (John Huston's The Misfits) just near the end of her life that hinted at how she might have aged onscreen. But even today most people prefer to remember her as she was in The Seven Year Itch – luminous and full of heartbreaking charm, a creature so impossible that's it's possible we imagined her.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.