You don't hear much about North Korea these days. It seems like only yesterday that Donald Trump was engaged in nonstop baiting of dictator Kim Jong-Un and the hermit kingdom online and off, but the Biden administration has made Russia and China, North Korea's erstwhile sponsor, a diplomatic priority, shifting the attention of the world to Ukraine and not Pyongyang. Rumours – so far unsubstantiated – that North Korea has offered 100,000 troops to aid Russia in Ukraine suggest that someone is longing for relevance.

I'm not sure what changed from when North Korea's missiles and nuclear program were an imminent threat to being able to shrug and mumble "Oh, that guy..." If anyone misses those days it's probably Kim Jong-Un, who genuinely seemed to enjoy the attention – even if his pop culture apogee was being played by Randall Park in the comedy The Interview (2014) after his father, Kim Jong-Il, was the puppet heavy in Team America (2004).

But the Democratic People's Republic of Korea will probably force itself back to the front of the queue again, which brings me to Tae Guk Gi, a 2004 South Korean war movie known as The Brotherhood of War in the English world, where it barely made an impression, while at home it was briefly the biggest domestic film of all time and a game-changer for the Korean film industry.

Tae Guk Gi begins with the excavation of a battlefield, where the remains of soldiers from the Korean War are being reverently dug up and identified. One body doesn't show up on any casualty lists, however, while its name, provided by artifacts found with the bones, matches that of a living veteran – an old man (Jang Min-ho) who asks his granddaughter to drive him to the site of the dig, after which the film rolls back over fifty years to the start of the war.

In Seoul in the summer of 1950 Lee Jin-tae (Jang Dong-gun) is shining shoes to support his family, hoping to send his younger brother Lee Jin-seok (Won Bin) to university. They live with their mute, widowed mother and Kim Young-shin (Lee Eun-joo), who lives with them along with her orphaned younger siblings, helping the mother run a noodle stand. They're poor people in a poor country, independent but divided and struggling to survive after years of occupation by Japan and China.

Jin-tae and Young-shin are engaged to get married, but everyone's plans are interrupted with North Korea's surprise attack on the South and the brothers are conscripted – press-ganged, really – into the army and sent to defend the desperate last stand at the Nakdong River, outside Pusan, before General MacArthur and the Americans enter the war in force with the landings at Incheon.

The Korean film industry was in a slump at the beginning of the new century, though director Kang Je-gyo had made a major hit in 1999 with Shiri, a thriller about North Korean sleeper agents running amok in the south. It was the first big-budget action picture made in the country, and Kang was able to pull together funding for a film about the Korean War thanks to his reputation. Shiri and Tae Guk Gi are considered the foundation for the modern Korean film industry, whose domestic box office became strong enough to create films and talent ripe for export.

In other words, no Kang, no Oldboy, Snowpiercer, Train to Busan, The Host or, most importantly, Parasite, which won four Oscars in 2019 and signaled South Korea's definitive arrival on the worldwide cultural stage alongside "Gangnam Style", BTS, Squid Game and Samsung – Apple's major rival in the cellphone market.

Jang Dong-gun, who plays the older brother, was a popular TV star and singer who became famous when his shows were exported to other Asian countries; he'd starred in action films like Anarchists (2000) and Friend (2001) and the military drama The Coast Guard (2002) before being cast by Kang. Won Bin is a TV heartthrob whose career after Tae Guk Gi would be briefly interrupted by mandatory national service in the South Korean army, which saw him volunteering for duty at the DMZ between the North and South for a year.

Lee Eun-joo began her career as a model and TV star; Tae Guk Gi was her biggest role before she committed suicide in her apartment in Bundang, just after graduating from university in 2005, leaving behind notes written in her own blood. She was only 24.

The Korean War film as a subgenre is pretty small compared to films about the First or especially the Second World Wars. It began with Samuel Fuller's The Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets! in 1951, alongside other films made during the conflict, ranging from cheapies (Tokyo File 212) to romantic dramas (One Minute to Zero) to comedies (Mr. Walkie-Talkie).

Films made after the war came to its unsatisfactory conclusion tended to have a somber, faintly defeatist tone – titles like The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954), The Rack (1956), Pork Chop Hill (1959) and The Manchurian Candidate (1962) – that tentatively set the tone for public reaction to the imminent war in Vietnam. Robert Altman's M*A*S*H (1970) was really a Vietnam film set during the Korean War, and pictures about the conflict since then have been few and far between, including two films about MacArthur (MacArthur and Inchon) and the upcoming Devotion, about a black pilot in the then-newly-integrated US Air Force.

South Korea was too busy fighting the war to make films about it until Piagol (1955), Five Marines (1961), The Marines Who Never Returned and Red Scarf (both 1963). From their perspective, of course, the war never ended, and the success of Tae Guk Gi led to films set during the three "hot" years of the war - A Little Pond (2009), The Front Line (2011), Operation Chromite (2016) and The Battle of Jangsari (2019) – and in the decades afterward. Northern Limit Line (2015) is about a naval battle between the North and South that took place during the 2002 World Cup, while thrillers like Shiri and even comedies like OK! Madam (2020) are predicated on the two Koreas being continuously at war.

China, for its own reasons, is suddenly interested in making Korean War films from its perspective, pressing into service directors like Chen Kaige (The Battle at Lake Changjin in 2021 and The Battle at Lake Changjin II in 2022) and Zhang Yimou (Sniper, released this year) – acclaimed directors who had once struggled to walk the line between artistic cinema with a global appeal (Chen's Farewell My Concubine from 1993 and Zhang's Raise the Red Lantern from 1991) and the Chinese government's pressure to make propaganda. Under Xi Jinping, the government is definitely winning.

Nobody, of course, believes these are period war movies as much as proxy battles between China and the U.S., fought and won by China onscreen.

Waiting behind the trenches at the Pusan Perimeter, the brothers get to meet the men in their squadron. Kang's innovation is to offer western moviegoers a story where the Korean War is fought by Koreans; most Hollywood films about the war almost entirely ignore not just the South Korean army (half of the force that fought against the North Koreans and Chinese) but the U.N. allies that arrived with the Americans – the Canadians, Australians, Turks, British, Belgians, New Zealanders, Ethiopians, French, Greeks, Filipinos and South Africans, alongside small contingents of soldiers and medical units from Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Denmark, India, Norway, Iran, Sweden and Italy. The only Americans we glimpse are journalists at a press conference, and the pilots we presume are flying the CGI Corsairs, B-29s and Sabres that provide air support.

Korea is an ethnically homogenous country, so instead of the cross-section of conscripted Americans that make up the classic infantry squadron in a World War Two film – the farmer, the college boy, the wise-cracking Jew and the Italian from New York City, the redneck, perhaps even the rare but not unprecedented Native American, Cajun or Latino – we get a gallery of types. There's Uncle Yang the older man, the rural rube, the shirker who resents being conscripted, the die-hard anti-communist eager for revenge after the murder of his family, the teenager who cracks under the strain and Yong-man, who leaves behind a wife and child when he's killed, ripping the heart out of the squad.

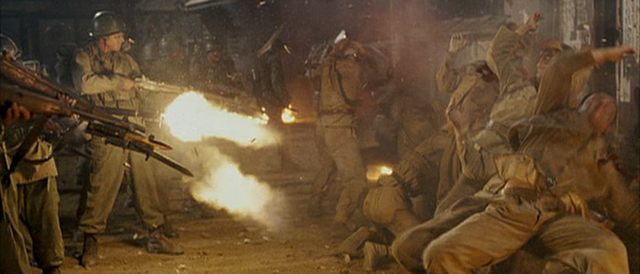

Like most war films, Tae Guk Gi is a melodrama, built on improbable plot points and emotional extremes. Jin-tae and Jin-seok are lucky enough to have a decent sergeant and officer leading them during the first months of the war, and Jin-tae is promised by the officer that if he wins the prestigious Medal of Honor, they'll send his brother home. He begins volunteering for dangerous, even suicidal missions, like the desperate night attack he leads with starving soldiers against the North Koreans at the Nakdong River – a frenzied battle in the dark that the film portrays as pivotal in holding the line while MacArthur cut off the North Koreans at Incheon.

The first year of the Korean War was the one that contained most of the action, with South Korean and UN forces retreating and advancing and retreating up and down the length of the country, all the way to the Chinese border until Mao sent in his army to bolster the North Koreans. Seoul was taken and re-taken multiple times, and the capitol temporarily moved to Busan. Tae Guk Gi shows Jin-tae, Jin-seok and their fellow soldiers crossing the border and invading Pyongyang on their way to the Yalu River.

Along the way they witness atrocities committed against civilians by the retreating North Korean army, including booby-trapped bodies at the site of a village massacre. Like the Marines in HBO's miniseries The Pacific (2010), this hardens them against their enemies, and they begin abusing and executing their prisoners. Jin-seok is particularly distressed by the change in his brother, who has taken to the task of becoming a war hero with a cruel determination that shocks him, especially when they find an old friend of theirs from Seoul among the prisoners who was press-ganged into the other side's army and Jin-seok has to plead for his life.

The men force prisoners to fight each other, placing bets and offering reduced punishments to the winner. Jin-seok jumps into the ring, bloodying himself and the POWs to force his fellow soldiers to feel some shame for their brutality. He questions his brother's motivations and blames him for the death of Yong-man, which drives a wedge between them.

When the Chinese force them back across the 38th parallel – quite literally a horde bursting over the border – the brothers find themselves near Seoul, where they both go AWOL separately to find if Young-shin and their mother are safe. They arrive just in time to see her arrested by student groups searching for people who collaborated with the Communists. They attack the students to try to save her from summary execution, but they fail, and she's thrown into a mass grave while both brothers are dragged away.

While Jin-seok is being held in a makeshift jail, Jin-tae tries to plead with the commanding officer, who's furious at him, a war hero, for killing anti-Communists. By this point the decent senior officers who had led them are dead or gone, and the garrison commander in Seoul is a far crueler man, who tells him the bargain he made with his officer was ridiculous and orders the jail set on fire before they retreat.

Jin-tae arrives too late to save his brother, and finds the silver pen he gave him at the beginning of the film next to a charred corpse. With the city now overrun, he sees the garrison commander being marched off with other prisoners, and joins them so he can beat the man's skull in with a rock.

The production team around Kang for Tae Guk Gi was young; special features included with the DVD for the film show them literally trying to invent how to make a war film from scratch, testing out explosive charges to see which ones gave the most realistic impression of an artillery barrage. There was only one digital effects house in the country, and one martial arts house that could train actors for battle scenes.

Films like Saving Private Ryan and the HBO miniseries Band of Brothers had raised the bar for visceral but realistic action scenes in war movies. Kang's crew struggled to get access to tanks and other vehicles, and even had to build a steam locomotive from scratch since the closest one available was in China, and filming on location there could have eaten up nearly a million dollars of their $12.8 million budget.

South Korean cinema has become famous for its dynamic action scenes, visceral violence and visual effects. Without the groundwork done by crews on films like Tae Guk Gi, though, there might not have been a Train to Busan, Oldboy, The Host, Extreme Job or The Admiral: Roaring Currents, the last two being the top-grossing Korean films in the domestic market to date.

Extras do not pirouette or clutch their chest when they're shot in Tae Guk Gi. Shells kick up geysers of dirt, not smoke, when they miss, and fountains of gore and viscera when they hit. Bodies disintegrate in the air and squibs from bullet impacts produce rich sprays of blood while the camera staggers and reels amidst the battlefield action. The old standards of war movie action had been definitively superseded by the end of the '90s, and Kang and his crew knew they had to keep up and innovate. The result is a film that readily descends into onslaught, an overwhelming experience that critics described as relentless and even unpleasant, though sometimes with approval.

In The World War II Combat Film: Anatomy of a Genre, Jeanine Basinger describes how war films became more violent, with advances in intensity and explicit gore moving forward gradually until the release of Saving Private Ryan in 1998. There was, of course, the infamous pair of hands gripping the barbed wire in Lewis Milestone's pre-code All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), but Basinger also points out Bataan, a 1943 picture about the fall of the Philippines where everyone in the squad dies at the end.

The obscure Beach Red (1967), directed by and starring Cornel Wilde, has a structure similar to Ryan, opening with a relentless half hour of combat as Marines assault a Japanese-held beach. "The bloody business is seen for what it is –" Basinger writes; "lost limbs, a severed foot or arm floating in the water or abandoned on the beach, flamethrowers and grenades reducing the enemy to ashes, dead bodies used as shields when advancing, vomit, the whole ugly thing."

The bar would be raised again with films like Sam Peckinpah's Cross of Iron (1977) increasing in pace with Apocalypse Now (1979), Platoon (1986), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and The Thin Red Line (1998). There were no explicit prohibitions against depicting realistic combat violence as much as an understanding of custom and standards that amounted to self-censorship – a Production Code ritual that meant "finding ways to clarify horrible events for viewers without directly representing them onscreen."

Basinger writes that it's a mistake to "assign an audience of the past the role of idiot and an audience of today the role of genius." War movie audiences of the '40s were far closer to real violence than we are – "they were losing friends and family every day, and welcoming home the maimed and wounded." It's plausible to imagine that we've seen war films become more graphic over the last few decades as we've become generations removed from experiencing war first or even second hand.

Behind the lines in a hospital it's revealed that Jin-seok didn't die in the jail fire but was saved at the last minute by Uncle Yang. He learns that his brother has become a propaganda coup for the enemy – the war hero who defected and now leads elite "Flag Unit" shock troops. His hatred for his brother by this point has hardened so violently that the formerly virulent anti-Communist in his squadron pleads with him to reconsider.

Jin-seok leaves the hospital and heads to the battle lines around the 38th parallel to confront his brother, disobeying orders and heading into enemy lines alone to find the Flag Unit and its leader. He end up caught in the latest attack, which is being won by the South Koreans and UN forces until Jin-tae and his men arrive and beat the allies back.

The men find each other but Jin-tae doesn't recognize his younger brother and, full of bloodlust, tries to kill him, the two men tumbling down the trench-scarred muddy hillside while shells explode around them. Kang's film finally makes explicit what it had been merely implying until then – that the Korean War was a national fratricide that would scar it for generations.

In the west we have different ways of understanding the Korean War if we think about it at all. It was World War 2.5, or a beta tester for Vietnam, or an experiment in seeing just how hot the Cold War could get before slipping into its terminal, nuclear phase. For Koreans, however, it was a civil war, and the interviews included with the DVD release of the film feature unanimous statements by cast and crew that it was awful and pointless, and that they would never agree to fight in anything like it again – the young people sounding not unlike pacifist students and intellectuals of the '30s, resolving that there wouldn't be a second World War if they had anything to say about it.

Korea was split in two around the same time that Germany was divided into East and West, and it was assumed that the South would be just as ready to embrace reunification when and if the day came that the Kim regime in the North fell. It's been over a generation since Germany reunited, however, and as the "war generation" in South Korea is slipping away, polls have shown that younger citizens in the Republic of Korea aren't as enthusiastic about reunification – or with maintaining an uneasy détente with the North at all costs.

A story from earlier this year noted how opinions among the young have become less accommodating, and even resentful of the 70-year status quo:

"Alarmingly, however, hostility and indifference are brewing underneath this change. As the sense of ethnic commonality diminishes, it's easier for younger South Koreans to view the North entirely through the lens of enmity...The share of South Koreans regarding the North as 'the enemy' has more than doubled since 2005, while those entirely indifferent to whatever happens up north saw a significant uptick."

It's not hard to imagine that, when we're forced to start thinking about North Korea again, our assumptions about what the wildly prosperous South want to do with their poor but dangerous Northern neighbour – now regarded as more "cousins" than "brothers," and perhaps not even that generously – will be challenged, and the potential for conflict in one more part of the world will have quietly increased.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.