Judith Durham died on Friday aged 79, at the Alfred Hospital in her home town of Melbourne. Hers is high up on a very short list of voices I would want to sing me into the hereafter, and I know that many other SteynOnline readers feel the same way about her. She kept almost all of that beautiful voice right to the end. Here she is in the Nineties, on a Seekers reunion tour, with a song that, notwithstanding its fairly appalling author, always touches me:

The Seekers were the biggest pop group ever to come out of the Lucky Country. They had a lot of hits around the world, but, when I was in Victoria eight years ago, this was the one that provided the title for the then new biotuner about them that was enjoying its world premiere at Her Majesty's Theatre in Melbourne. I had a grand old time at it.

But, like most of their big songs, it started a long way away from Australia - in this case, with the novelist and biographer Margaret Forster. I can't claim to have known her, but I enjoyed a quarter-hour of pleasant conversation with her a gazillion years ago back when she was, if memory serves, either a judge or nominee for some literary prize and I was covering it for the BBC's "Kaleidoscope". Her husband Hunter Davies has been a Beatles biographer and Punch columnist and whatnot, and a familiar sight on the London media scene, one of those chaps who chose the writing life, one suspects, as much for the social pleasures it affords as for any literary ones. But his wife was famously uninterested in the celebrity circuit, and it was well known among Beeb producers that she said no to 99 out of 100 interview requests.

She had a global smash with her second novel, written at the age of 27, and she surely must have accepted at a certain point that that particular lightning would not strike again and that her obituaries would be headlined "Georgy Girl Writer Dies". But without Miss Forster we wouldn't have had the book. And without the book we wouldn't have had the film. And without the film we wouldn't have had:

Hey there, Georgy Girl

Why do all the boys just pass you by?

Could it be you just don't try?

Or is it the clothes you wear?

Georgy Girl (1965) told the story of an awkward galumphing working-class lass in the new London faced with the unsatisfying romantic choice of a dour older man who's her dad's boss or, alternatively, the errant lover of her glamorous and promiscuous flatmate. It was a hit, and Miss Forster used £4,000 of her royalties to buy her mum a bungalow. The following year it was turned into an even more successful film with Lynn Redgrave as Georgy and a stellar supporting cast - James Mason, Alan Bates, Charlotte Rampling, and Lynn's own mother, Rachel Kempson. Miss Forster adapted the novel with the playwright Peter Nichols, and they turned in a taut, tart script on contemporary London life: "God always has another custard pie up his sleeve," as Miss Redgrave remarks at one point.

Three years before young Margaret Forster wrote her novel, on the other side of the world in Melbourne, Victoria, three Australians had formed their own antipodean version of the Kingston Trio - Athol Guy on double-bass, Bruce Woodley on guitar, Keith Potger on 12-string guitar. Guy's day job was in advertising, and one day leaving Channel Nine he mentioned to Beverley the receptionist that he thought his little trio might benefit from a lady singer. As it turned out, Beverley's sister Judy was a singer, and at that very moment she chanced to telephone, and Beverley put her on to Athol, who promised he'd come hear her sing.

Not long after, Judy applied for a job at J Walter Thompson, and was astonished to discover on her first day that also working in the ad agency was the bloke her sister had put her on the phone to, Athol Guy. At the end of that afternoon - December 3rd 1962 - Guy took her along to the trio's gig at the Treble Clef on Toorak Road, and three dozen of their fellow Melburnians heard for the first time a new quartet. And thus boys met girl: Judith Durham of the bell-like vocal tones that once heard are unmistakeable. Her crystalline voice is in a league of its own, but all four sang, and their voices blended beautifully, which is what it's really about. As Athol Guy said:

A lot of groups can sing harmony but a lot of them don't blend. We blended normally because of the timbre of our voices and we recognized we were really good harmony singers... We were lucky. The first time we opened our mouths together, we said that's the sound. That's what we want. You sing through your ears most of the time and then you blend in. Harmonies are one thing, but to get a really good blend that we got, it's quite unique. You've got to have a really great lead singer to be able to do that. And you've got to have a lead singer that forgets that they're the soloist. They have to hold the notes while you wrap the harmonies. It just happened. It was wonderful.

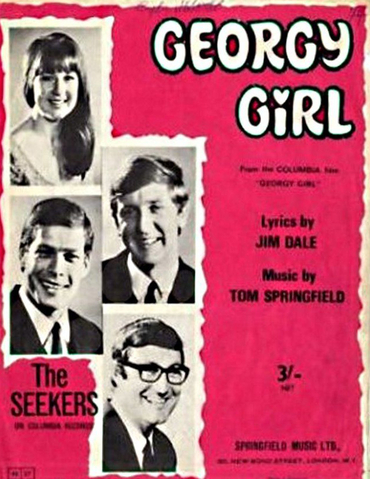

In 1964, two years after getting together, The Seekers set sail for Southampton on the SS Fairsky. They paid their passage by singing on the ship - as The Seekers in the afternoons and as the house rock'n'roll band in the evenings. And they figured they'd have ten weeks in Britain, see if they could get any work, and then come home. They sent ahead their eight-by-tens and a first album to an agent called Eddie Jarrett. He liked what he heard, and had a brilliant notion - to put The Seekers together with a composer called Tom Springfield. Tom had been part of his own Seekeresque group called The Springfields with his sister and a pal. The Springfields had had UK hits with "Island Of Dreams" and "Say I Won't Be There" - and "Silver Threads And Golden Needles" had been an Aussie Number One, so they were known Down Under. But then Tom's sister Dusty went off to pursue, as they say, a solo career and no one had any need for a Dusty-less Springfields.

So Tom decided, faute de mieux, to focus on his songwriting and producing - and once he found The Seekers neither party looked back. They met Dusty first, and Dusty introduced them to Tom, who sold Keith a twelve-string guitar. His first song for them was "I'll Never Find Another You", which reached Number One in the UK and Oz and won the Seekers the Best New Group prize at the Top of the Pops Awards:

They were untypical pop stars, eschewing drugs and groupies and leaving hotel rooms neater than they found them. Ensconced in a windowless bedsit in London's Aussie quarter of Earls Court, Judith Durham made her own frocks based on the Queen's. "I felt that's how a lady is supposed to dress," she told The Sydney Morning Herald. "I had my matching handbag and gloves, everything."

And then came Georgy Girl. If you're making a film, you need a theme song – or you did in those days. Sometimes a movie theme is just a bit of aural filler to play over the credits. But sometimes, more rarely, it enlarges the picture, and implants the title out there in the wider world. There are very few people who were young in 1966 for whom the phrase "Georgy Girl" isn't automatically preceded by the words "Hey there..."

Dreamin' of the someone you could be

Life is a reality

You can't always run away...

The tune was, naturally, by Tom Springfield, and so strong that it attracted an unusual number of instrumental recordings. Even on the Seekers recording, the whistling intro (possibly not humanly-generated) sells you on the song before a word is sung. For some reason the lyric fell to Jim Dale. To 21st century children around the English-speaking world, Jim Dale is the guy who made long car journeys bearable, as reader of the Harry Potter audio books. To Gitmo detainees, he's the infidel devil that the Great Satan uses to torture them, pumping the same Harry Potter stories into their cells as aural disorientation. To 1980s Broadway audiences, he's the unforgettable star of Barnum and Joe Egg. But back in Britain in 1966 he was the boyish charmer of the unending series of low-budget trouser-droppers, the Carry On films. I met him in New York after the run of Barnum, and he told me he still got a laugh every time he passed a store called Ballocks, because in a Carry On it would be the name of Sid James' character or the restive Afghan tribe threatening the colonial governor or the name of the new medical device Hattie Jacques wants to insert into Kenneth Williams.

I can't remember his explanation for how a Carry On actor got to write a movie song for Lynn Redgrave, James Mason and Alan Bates, but he gave the impression that in Swingin' London back then everyone knew everyone (Michael Caine was John Barry's flatmate, etc) so he had a go at songwriting and found he rather enjoyed it. In case you're wondering, his other big song was "Dick-A-Dum-Dum". Des O'Connor had the hit with it; yet no disrespect to Des but I have always preferred the composer's original. If you can get beyond the faintly preposterous hook, this is an even more precise time capsule of the Carnaby Street era than "Georgy Girl", with its references to go-go girls, boutiques, mini cars, Kings Road... And of course each section ends with a highly emphatic "giiiiiirrrrl", whether of the real sweet, real cute or real shy variety:

"Dick-a-Dum-Dum" is perhaps a bit too particular ever to take off quite the way "Georgy Girl" did. "It's a brilliant lyric," said Judith Durham of the latter, "especially for me with my self-esteem problems. It's always been the perfect lyric for me to sing":

Hey there, Georgy Girl

Swingin' down the street so fancy-free

Nobody you meet could ever see

The loneliness there

Inside you...

For a dilettante moonlighting from his trouser-dropping day job, that's pretty solid and professional: The "hey there" on those big opening notes, and then the "swingin' down the street" as the tune takes off swingin' and swayin' and wigglin'. And he's even got some internal rhymes in there: "Swingin' down the street"/"Nobody you meet". That parenthetic "Inside you" is a very nice touch on Springfield and Dale's part, and it's reprised not, as you might expect, in the next main-theme section but at the end of the release;

You're always window shopping

But never stopping to buy

So shed those dowdy feathers and fly

A little bit...

The tune is Swingin' London at its most buoyant and sunny. The street it's swingin' down so fancy free is Carnaby Street - a leggy girl in mini-skirt swingin' past the groovy boutiques in the lunch hour of an endless sunny afternoon. It's also one of the all-time great whistling records - not whistling as in the sense of Bing and Jolson, as a kind of instrumental break halfway through the record: "Georgy"'s whistling, whether humanly or machine generated, seems to be embedded as an indispensable part of the arrangement, if not of the composition itself. And who needs big studio music-department orchestras? "Georgy Girl" has acoustic guitar, hand-claps for percussion, and never sounds as if it wants for anything else. And the beautifully blended voices of the Seekers are about the fullest sound you'll ever need - which is why solo singers approach this song at their peril. The tune's breezy optimism is a wee bit at odds with the film, which is a somewhat bleak kitchen-sink drama, and in black-and-white to boot. But Jim Dale's lyric bridges the music and the movie:

So shed those dowdy feathers and fly

A little bitHey there, Georgy Girl

There's another Georgy deep inside

Bring out all the love you hide

And, oh, what a change there'd be...

The whistling and sunniness are that other Georgy deep inside: what she could be when she's shed those dowdy feathers and is flying - not "a little bit" but soaring sky high.

Jim Dale told me a story all those years ago that I didn't quite believe – about auditioning the song for a couple of grizzled old bruisers who demanded certain changes or "Frank won't sing it". As in Sinatra. "It doesn't woik for him," Dale mimicked the boys saying.

Could be, I suppose. Could have been Sarge Weiss or Hank Sanicola, Frank's two associates in such matters. On the other hand, it's hard to conceive of the changes you'd have to make to "Georgy Girl" to get Frank to sing it. On the other other hand, he sang "Winchester Cathedral" and "Downtown" without any changes, so who knows?

In the event, "Georgy Girl" didn't need Frank. The Seekers' record got to Number Three in Britain, Number Two in America and, of course, Number One in Australia. It's the song that made them stars beyond the British Commonwealth: Their album Come The Day was quickly re-labeled Georgy Girl for its US release. It was nominated for an Academy Award, and would have been the first British song to win an Oscar, except it lost to another Brit hit "Born Free" (by John Barry and Don Black). The above-mentioned biotuner that I saw at Her Majesty's in Melbourne has a scene in which the Seekers are thrilled by the Oscar nod and assume they're Hollywood-bound to sing it on the big night. Under some since discarded rule, alas, the artist who sings it on screen was not permitted to sing it on the awards show, and, somewhat to the group's horror, the producers elected to give it to the very embodiment of the Anti-Judith Durham - Mitzi Gaynor. Stay tuned for the point at which she takes her dress off:

As you can tell from the cheers, that was one of the most rapturously received Oscar numbers in history. My own view is that the entire gay rights movement dates not from the Stonewall Judy Garland riots but from the moment Mitzi Gaynor removes her frock and every homosexual in North America decided to shed his dowdy feathers and fly a little bit.

By way of consolation, a month earlier at the Sidney Myer Music Bowl in Melbourne, the Seekers had sung the number to a record-breaking crowd of over 200,000 people - one tenth of the city's then population, and the largest live audience ever in the southern hemisphere. Like the queen whose fashions she followed, Miss Durham kept her clothes on.

The Aussie rock journo Ian McFarlane famously characterized The Seekers as "too pop to be considered strictly folk and too folk to be rock". But that's only a problem for rock critics obsessed with pigeonholing. The Seekers didn't need to worry about being too this or too that, because they were very good at being The Seekers - if only for a while. In 1968, six years after getting together, they split up to go seek something else. Their final hit was another Tom Springfield song with an elegaic title:

"The Carnival Is Over" remains one of the thirty biggest-selling singles of all time in Britain. But the last song they sang on their farewell concert for the BBC was inevitably "Georgy":

But the carnival is never over, it just moves on. So a few years later guitarist Keith Potger sought out a group of new Seekers that he called The New Seekers. They had a monster planet-wide hit in 1972 with a famous Coke jingle, "I'd Like To Teach The World To Sing", but there was something about the old Seekers that the new ones never quite found. You can hear the difference in the New Seekers' cover of the old ones' "Georgy Girl" on the album We'd Like To Teach The World To Sing. And not so long after that the New Seekers went away and the old Seekers came back to (somewhat fitfully) stay.

Lots of Top Five records from the Sixties seem locked in their time. But this somehow both captures a moment and transcends it: A few years back, when Rolling Stone listed its Top 500 Songs of All Time, "Georgy Girl" was Number 36. Which is to say that there are only thirty-five songs ever written that Rolling Stone considers better than this one.

In a way the success of the song hurt Margaret Forster's book, or at any rate potential adaptations thereof. "Every few years someone tries to turn Georgy Girl into a musical," Jim Dale said to me. "But you can't do it without that song, can you?" In fact, you can't even use the book's title - because the moment you announce the forthcoming Broadway smash Georgy Girl: The Musical, everyone expects to hear:

Hey there, Georgy Girl

Swingin' down the street so fancy free...

So the 1970 Broadway version had to go under the name of Georgy, which isn't half as strong. Nor was its title song. The score was by George Fischoff and Carole Bayer, who became better known as Carole Bayer Sager, writer of hits such as "Arthur's Theme", "On My Own", "Nobody Does It Better", etc. But in Georgy she couldn't deliver anything that matched the work of Dusty Springfield's brother and the juvenile lead of Carry On up the Khyber.

Eight years ago "Georgy Girl" finally did become the title song of a musical - the only musical it could really be, a show about The Seekers and their many hits that opened just before Christmas in their hometown of Melbourne. They're known for a handful of hits in America, and they're beloved in Britain, but in Australia they're legends. Indeed, in 2014, when I heard that all four had been made Officers of the Order of Australia in the Queen's Birthday Honours, my initial reaction was astonishment that it had been taken long. My God, they put Rolf in the Order of Australia in 1989 (since revoked) and even the bloody Wiggles in in 2010. But The Seekers don't really need any of that stuff, do they? Not when you can harmonize and whistle and clap hands, and you have a song that's eternally young:

Hey there, Georgy Girl

There's another Georgy deep inside

Bring out all the love you hide

And, oh, what a change there'd be

The world would see a new Georgy Girl(Hey there, Georgy Girl)

Wake up, Georgy Girl

(Hey there, Georgy Girl)

Come on, Georgy Girl...

Judith Durham never tired of singing it, because somewhere deep inside she always remembered the Judy Girl sitting in an Earls Court bedsit sewing her frock and dreaming of the Judy she could be. Late in life, she took to starting the song with a little colla voce intro that was just lovely - and, as always with Judith Durham, utterly sincere:

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in the Land of Lockdown. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Herman's Hermits to Liza Minnelli; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from house arrest without end.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and the above column makes you want to shed your dowdy feathers and fly off the handle, feel free to clip his wings in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.