In his book Banging Your Head Against a Brick Wall, the graffiti artist Banksy said that "your mind is working at its best when you're being paranoid. You explore every avenue and possibility of your situation at high speed with total clarity." How much faith you put into the truth of this depends only notionally on how you feel about Banksy, whether graffiti is art, and the trust you put into anyone whose career is based on anonymity and the contemporary art world as a forum for his wisdom.

What sinks the quote for me is the second sentence, which presumes that fear sharpens the senses and helps us make better decisions. Nothing I've experienced makes me believe that this could be more than occasionally true, and even then only when our frightened choice coincides with luck.

Paranoia is a pit stop in the road race to madness, and as such a very poor foundation upon which to build a worldview. But the more politics resembles a b-movie, the more people have realized that they like to be afraid, which brings us to John Carpenter's 1988 sci-fi political action movie satire They Live, a cult movie that's come to occupy an outsized space in how we relate to our politics – and each other.

They Live was the last film Carpenter released in the '80s, and some say the last really great film he made, after the success of Halloween in 1978 set him up to start the decade with two big hits (The Fog and Escape from New York) and a flop (his 1982 remake of The Thing) that's generally acknowledged as his best picture. The '80s were a great decade for Carpenter, but the feeling wasn't mutual, which is why he closed it out with an attack on the political and cultural morality of Reagan's America and the "greed is good" era.

The film begins like a western, with a lone drifter wandering into a rough town looking for a job. The drifter is nameless onscreen, and only the credits give him the name Nada, which Carpenter brought forward from artist Bill Wray's 1986 comic adaptation of Ray Nelson's 1963 short story "Eight O'Clock in the Morning." Nada is played by Roddy Piper, then famous as Rowdy Roddy Piper and a superstar in the WWF – professional wrestling's big league.

Piper's superficial resemblance to Kurt Russell – Carpenter's preferred star in many of his previous films – led to speculation that the role was written for Russell, but Carpenter insists that he always imagined the part as Piper's. A big wrestling fan, the director met Piper backstage a year earlier at Wrestlemania III, and saw in Piper a humanity and regular guy appeal he wanted for his film's protagonist.

For the first part of the picture Piper's Nada is the classic loner hero – taciturn and stoic. All we know is that he's been pushed west from Denver to L.A. looking for a job, which he finds on a construction site where he meets Frank (Keith David), who's come all the way from Detroit, where he had to leave his family behind. They end up finding food and shelter in a shantytown across from a church that isn't what it seems.

The standard horror sci-fi film would have something unsavoury – perhaps even satanic – happening in the church, but all that Piper finds when he sneaks in is a tape machine playing a recording of a choir while the blind preacher works with some sort of covert group of rebels, who are trying and failing to hijack the TV airwaves to broadcast their message of a sinister conspiracy.

Carpenter based his movie's homeless encampment on Justiceville, a Los Angeles shantytown that only existed for the first five months of 1985 before it was raided and bulldozed by police. "I was reflecting on a lot of the values I saw around me at the time, mainly inspired by Ronald Reagan's conservative revolution," he said in an interview. "There was a great deal of obsession with greed and making a lot of money, and a lot of the values I had grown up with were being pushed aside. And I decided to scream out in the middle of the night and make a statement about that."

In the movie, that scream is first heard as a lo-fi broadcast sporadically breaking into the TV signal, with a bearded, bespectacled man ranting that "the poor and the underclass are growing...they have made us indifferent to ourselves, to others...they are dismantling the sleeping middle class...Earth is being acclimatized – they are turning our atmosphere into their atmosphere."

It's a primer of paranoid conspiracy that Carpenter wants us to understand as politically explicit; as a member of the rebel group explains later in the film: "They're free enterprisers. The Earth is just another developing planet. Their third world." Embedded with the paranoia there's a component of the pirate signal that causes headaches in viewers, who react to it with either confusion or resentment.

Sneaking around the church, Piper discovers boxes of sunglasses, and after the police clear the shantytown – a terrifying scene lit mostly by red flares, shot by Carpenter and his crew in a single night – he heads back to find the sunglasses hidden behind a false wall in the now-empty church. He hides the box in an alleyway and, almost as an afterthought, puts on the glasses, and this is where the movie really begins.

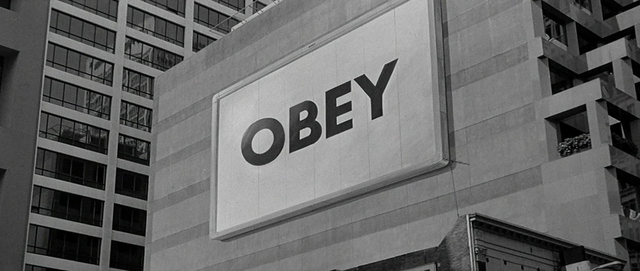

Those sunglasses, and the scene where Piper wanders the street taking in the world through them, have become They Live's contribution to pop culture and political discourse. (Just Google "they live sunglasses" and see what I mean.) The world seen by Nada through the glasses is in black and white, where the first obvious difference is that every billboard and sign, newspaper and magazine is stripped of everything except a handful of boldface, all-caps slogans, repeating the same messages over and over:

WATCH T.V.

OBEY

NO INDEPENDENT THOUGHT

CONSUME

MARRY AND REPRODUCE

STAY ASLEEP

BUY

CONFORM

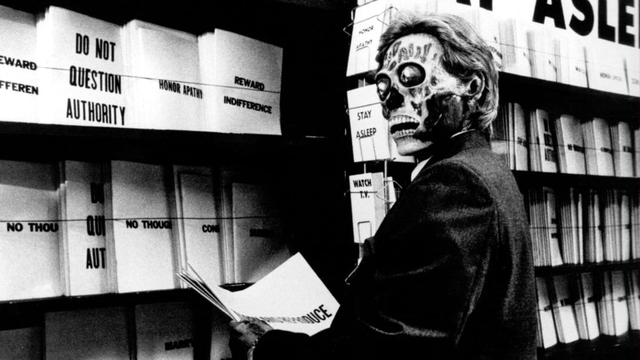

Hammering home the message, dollar bills seen through the glasses simply read "THIS IS YOUR GOD." But most troubling of all, the glasses reveal at least half of the population on the street as grotesque humanoid monsters, skinless and lipless, with lifeless, metallic bug eyes.

The Slovene philosopher Slavoj Žižek devotes quite a lot of thought to They Live in his video essay The Pervert's Guide to Ideology. "When you put the glasses on, you see dictatorship in democracy – it's the invisible order that sustains your apparent freedom," Žižek says. "The explanation for the existence of these strange ideology glasses is the standard story of Invasion of the Body Snatchers: humanity is already under the control of the aliens."

This should be obvious to anyone with even a little knowledge of film history, but Žižek goes on to say that:

"Ideology should be glasses that distort our view, and the critique of ideology should be the opposite – you take off the glasses so you can finally see the way things really are. This is precisely where the pessimism of the film is well justified; this precisely is the ultimate illusion. Ideology is not simply imposed on ourselves – ideology is our spontaneous relationship to our social world, how we perceive each meaning and so on and so on. We, in a way, enjoy our ideology. To step out of ideology, it hurts, it's a painful experience. You must force yourself to do it."

Carpenter makes this explicit with the headaches Piper suffers from whenever he puts on the glasses. That doesn't of course, stop him from going on the offensive almost immediately after the truth has been revealed to him by the glasses.

Even if you didn't have the magic glasses, one sure tip-off that you're dealing with an alien is that nearly every one of the creatures (Carpenter's script only occasionally refers to them as "aliens," preferring the terms "ghouls", "the living dead" or "zombies") is a rude, entitled jerk. This puts Nada's back up even more, and it isn't long before he's on the run from the police after the creatures in a supermarket alert the authorities on their wristwatches that "we've got one that can see."

Within a few minutes he's killed a couple of aliens in police uniforms, and a minute after that he's on the run with the dead cops' weapons, walking into a bank half full of the creatures and pronouncing the film's most famous line:

"I have come here to chew bubble gum and kick ass. And I am all out of bubble gum."

After massacring the aliens in the bank and shooting down one of their flying saucer-like surveillance drones, Piper manages to escape by kidnapping Holly, a well-dressed woman (icy-eyed actress Meg Foster) and forcing her to drive him to her home in the Hollywood hills. But she gets the drop on the exhausted Nada, breaks a wine bottle over his head and pushes him out a window several storeys to the ground. (You know you're watching an '80s action film not only when a slight woman can punch the hulking Piper out a window, but when he only limps away, apparently back to full strength the next day, possessing apparently abundant health points as if he's in a video game.)

I didn't see They Live when it came out back in 1988. (I was a major film snob, and it looked too b-picture for me.) But I did see stills from the film, and the boldface slogans/alien orders revealed by Piper's glasses put me in mind of two conceptual artists who had become major celebrities in the art world boom that was just one of the aspirational, cash-crazed bubbles formed during the '80s.

Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger were two New York artists whose work involved provocative text, printed in boldface and exhibited everywhere from postcards to billboards. It was easy to confuse the two of them, though Holzer's work was slightly more explicit:

Your Oldest Fears are the Worst Ones

If Not Now Then When

Abuse of Power Comes as No Surprise

Protect Me From What I Want

It Is Heroic To Try To Stop Time

...while Kruger's work was a bit more ironic:

I Shop Therefore I Am

We Have Received Orders Not To Move

I Win You Lose You Win I Lose

We Don't Need Another Hero

Plenty Ought To Be Enough

There was also nothing new about the idea that advertising and mass media was engaged in the business of coercive propaganda; Wilson Bryan Key had a bestseller with the mass market paperback Subliminal Seduction in 1974 (my mother had a copy on her bedside table for years) while Vance Packard published The Hidden Persuaders as far back as 1957.

The idea that mass media was shaping and commanding our desires as consumers informed the work of artists like Holzer and Kruger, who simply created slogans that were alternately critical or satirical and imagined them inserted into mass culture alongside the usual, increasingly strident advertising campaigns. But their art would never have worked if there wasn't a general assumption that mass media wasn't already engaged in giving us commands.

Žižek's idea that freedom is painful gets underlined wildly in They Live's famous fight scene, where Nada tries to force Keith David's Frank to put on the glasses. Frank, shocked at Nada's massacre at the bank, wants nothing to do with him, so the two men begin a brawl in an alleyway – a scene that took two weeks to rehearse and five precious days of shooting to film.

Inspired by the wild, almost exuberant brawl between John Wayne and Victor McLaglen in John Ford's The Quiet Man (1952), Carpenter wanted to create a scene that the audience could feel – while also satisfying Piper's fans by featuring classic moves from the wrestling ring. It's frequently cited as one of the greatest movie fight scenes, but it's always looked more than a bit ridiculous to me, and not only because any ten seconds of damage inflicted on either man would put the average human in traction for a month – if they could actually survive a whole minute.

Žižek again:

"It's the weirdest scene in the movie. The fight takes eight, nine minutes. (Really only five and a half minutes, though I can see why it might seem longer.) It may appear irrational because why does this guy reject so violently to put the glasses on? It is as if he is aware that he lives in a lie, that the glasses will make him see the truth, but that this truth can be painful, can shatter many of your illusions. This is a paradox we have to accept. The extreme violence of liberation – you must be forced to be free. If you trust simply your spontaneous sense of well-being or whatever you will never get free. Freedom hurts."

In the end Piper forces the glasses on Frank, who has the same dispiriting revelation of the truth before, like Nada, deciding to join the resistance and strike the first blows for freedom.

They Live was a b-picture with considerable ambition, and its evolving reputation over time has vindicated the esteem with which the director holds the picture. Carpenter calls his film "a documentary about what's going on now," and the film's abiding half-life as a meme generator suggests that he's not alone.

The artist Shepard Fairey rose to fame with his Barack Obama "Hope" poster, but his first big "hit" was his graphic portrait of wrestler Andre the Giant above the word "OBEY", and a poster featuring details from a US dollar and the slogan "THIS IS YOUR GOD", which was also the title of a 2003 exhibition of his work.

His work was (astoundingly) a simplification of Holzer and Kruger's, and openly acknowledged the influence Carpenter's movie has had on it, with the artist saying that They Live "has a very strong message about the power of commercialism and the way that people are manipulated by advertising." On a more grassroots level, social media is full of memes using Nada to satirize Elon Musk or vaccine protesters or Donald Trump.

But it also has to be pointed out that Piper and his sunglasses are even more frequently enlisted to visualize "red pill" moments and, despite Carpenter's own politics, the image has become a staple of conservative, right-wing and "alt-right" memes. The bug-eyed aliens and their slogans can be replaced by Mark Zuckerberg or woke corporations or BLM or climate change or Klaus Schwab or whatever enemy with a hidden agenda needs to be called out.

In a 2018 essay in The Ringer, Steven Hyden writes with obvious enthusiasm about the political resonance of They Live, but notes that as the film "became a home-video mainstay during countless middle-school sleepovers, 'giving the finger to Reagan' mattered less and less to millions of teenagers." Among the fans that the picture accumulated as it moved from second run and VHS rentals to DVD and Blu-ray was InfoWars host Alex Jones, who called it "one of my favorite all-time movies," and that he'd "probably seen it 100 times. It breaks down everything!"

Jones had Piper on his show as a guest in 2013, two years before the wrestler's death, where Piper admitted to being a big fan of Jones. It's easy to imagine Jones as the ranting man on the rebels' pirate TV signal in some remake of the film, though with the dawn of the internet any reboot of They Live would require an extensive rewrite that would alter the essence of the story. It's a testament to the power of Carpenter's vision that conservatives have been able to embrace it so uncritically; it's hard to imagine how "Marry and Reproduce" could be sold to them as a sinister message.

Just over a decade after the release of They Live, conspiracy theorist David Icke published The Biggest Secret, claiming that shape-shifting lizard people controlled society. Having become unmoored from its creator's politics and taken on a life of its own, Carpenter was obligated to post a denunciation on Twitter in 2017, of anti-Semites and neo-Nazis who'd embraced the film as an analogy for Jewish control of the media, which the director called "a slander and a lie."

I can't imagine Carpenter could have imagined a time when even mainstream conservatives would be openly distrustful not just of the media but of corporations and even their own parties. Contempt for authority has migrated and collected on the other side of the political spectrum in the last three decades, and the rhetoric and imagery of They Live has been swept along with it.

In the film, Nada and Frank infiltrate a gala meeting of the aliens and their human collaborators where the keynote speaker predicts a "total takeover" of Earth by 2025, and thanks the "human power elite" present for their assistance in the aliens' "multidimensional expansion." So it's hard not to hear an echo of the film in a recent video by right wing YouTuber Paul Joseph Watson, railing against the "predator class elite."

There's even a YouTube essay on the Collative Learning channel where the author suggests that the aliens of They Live might be even more enslaved than the humans. It's an idea that starts with the logical flaw between the film's title and the frequent descriptions of the aliens as "ghouls" and "the living dead."

"How can They Live if they're dead?" the author wonders.

He points out that the aliens have integrated themselves so completely into human society that they work and socialize and even have sex with humans – often as peers. And while the humans can't see the hidden messages all around them without the sunglasses, it has to be assumed that if the aliens can recognize each other, they can read them clearly – and constantly.

"They see humans as enslaved to them, yet they don't see how they are enslaved themselves...Being that they have high paying job positions, it's arguable that they are more dependent on the system; they've got more to lose, whereas our mostly homeless rebels have already hit near-rock bottom, so the only way is up."

When Žižek recalls Invasion of the Body Snatchers he doesn't note how, with the decades, Don Siegel's 1956 sci-fi film shifted from being a metaphor about communist infiltration to a more broadly paranoid story about conformity, culminating in Philip Kaufman's 1978 remake, which resonated with boomers anxious about abandoning their youthful ideals. (Imagine it as The Big Chill with pod people; it's easy when you realize that Jeff Goldblum is in both films.)

Like these pictures, They Live invites us into a paranoid vision of our friends, neighbours, co-workers and even family betraying us by becoming something other – a creature that doesn't share our values; that will exploit us; that is essentially less than completely human.

At one point during the film, when they're holed up in a skid row hotel, Frank wonders aloud to Nada about the aliens: "Maybe they've always been with us, those things out there. Maybe they love it, seeing us hate each other, watching us kill each other off."

I can't help but shudder when I read Žižek talking about the "extreme violence of liberation," and how "you must be forced to be free." How much violence, and who will do the forcing? And while we're on the subject of "ideology glasses," isn't it worth wondering how different They Live would be if the glasses actually created a paranoid fantasy instead of revealing a truth?

Imagine how the story plays out if Nada killed two cops trying to de-escalate a situation, or simply shot random customers in a bank. It's not hard since Carpenter's script isn't exactly a masterpiece of character development or motivation, and one that happily puts dialogue like "Beat your feet!" and "Mama don't like tattletales!" and "Brother, life's a bitch...and she's back in heat" in its heroes mouths.

The fact is that we've reached a point where we're mining b-movies for political wisdom; it's probably only a matter of years until a major political candidate runs – and wins – on a campaign ad that tells us that they're "all out of bubble gum." (Which brings us to Mike Judge's Idiocracy, a movie whose political satire was more frighteningly prescient than They Live.)

We've put a lot of weight on a movie that aimed to radicalize wrestling fans when it was released the week George Bush won a landslide, and ended up making it easier for us to imagine the other half of the world as a bit less human. How long until election campaigns will be mining Dragon Ball or Squid Game for memes to sway youth voters. Considering the iceberg that is social media, that day is probably already here.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.