In Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen wrote that there is "something so amiable in the prejudices of a young mind, that one is sorry to see them give way to the reception of more general opinions." I can't pretend that my prejudices as a young person were amiable – my attitude between 12 and 30 was probably best described as hostile. But Austen's quote sums up how we feel about revisiting youthful enthusiasms years after we've moved on to, if not more general opinions, perhaps more refined ones, and definitely far away from whatever anxiety and insecurity conditioned our taste.

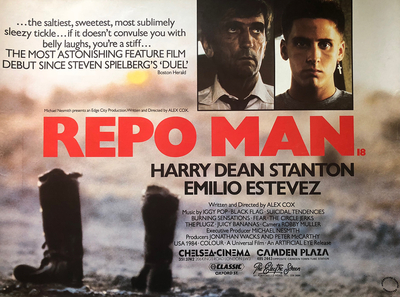

It's why sane people approach our old favorites with caution: older eyes and minds can't see them with the same freshness and context (or lack thereof). I've been sorely disappointed by revisiting films or books that I once loved, a dismal emotion that pushes that memory of a younger person and everything they cherished even further into the past, making them a stranger that happens to share your name and history. It's why I questioned the wisdom of revisiting Repo Man (1984), director Alex Cox's cult picture about punks, lowlifes and aliens in Reagan-era Los Angeles.

Or, as the film's protagonist Otto (Emilio Estevez) says while watching a band in a sleazy bar: "I can't believe I used to like these guys."

Cox was an unknown, a former film student who'd moved from Britain to Los Angeles, struggling to get a break in the movie business when a screenplay he'd written about repossession agents – the automotive versions of bounty hunters who legally steal cars from owners behind on payments – got him the attention of the movie business, and on to the first step of what usually ends up as development hell; one of thousands of pictures that bounce around for years without getting made.

Cox, working with fellow first time producers and fellow UCLA grads Jonathan Wacks and Peter McCarthy, managed to luck out when a script, complete with a six page comic book teaser for the film drawn by Cox, landed in the hands of ex-Monkee, Liquid Paper heir, movie producer and music video pioneer Mike Nesmith. Nesmith managed to shepherd the film to Universal Pictures, where it was given a "negative pickup deal," meaning that Nesmith and Edge City – Cox, Wacks and McCarthy's production company – were on the hook for all the expenses up until they could deliver a finished picture to the studio.

This meant that Repo Man would be made for a very low budget, with extra incentive to finish on time, and no guarantee that it would get released or, if it was, that it would enter theatres with any promotional backing. In other words, the perfect conditions to make a cult film.

Like most cult pictures, Repo Man is a bit of a mess from structure to themes, the chaos of its production only barely contained onscreen. This is probably what attracted me to it so avidly in 1985, just a few months after it was offhandedly released by Universal, and just about the time my tenure as an undergraduate was stumbling to a premature and unimpressive end.

The film begins, as most cult pictures should, with some pretty weird, cheesy business. A 1964 Chevy Malibu is weaving along the I-40 on its way from Los Alamos to Los Angeles through the Mojave, just outside Needles. Pulled over by a motorcycle cop, the driver of the car – a jittery man with one lens missing from his sunglasses – tells the cop not to look in the trunk. Which he does, of course, vaporizing him in a flash of light, leaving only his smoking boots and an oily scorch mark.

The next scene introduces us to Otto, working as a stock boy in a supermarket, stacking the shelves with the no-name blue and white tins (often just labeled as "beer", "drink" and "food") that we'll see throughout the picture. Desperate to save money, the producers had tried to get a sponsorship with a brand or chain, but lucked out when the Ralphs supermarket chain gave them access to a warehouse full of expired generic product – a visual touch that firmly places the film and its inhabitants at the lowest level of the consumer food chain. The only other sponsor they were able to get was from the Car-Freshner Corporation, who make the little scented Christmas trees that hang from rear-view mirrors.

Otto is a self-described "white suburban punk" who gets himself fired after he curses at his boss, pushes his co-worker Kevin (Zander Schloss) into a pile of tinned peaches, and flips off the store's armed security guard. Things get worse when he loses his girlfriend Debbi (Jennifer Balgobin) to his fresh-outta-juvie buddy Duke (Dick Rude) at a party. Wandering the decidedly rundown streets of downtown L.A., he meets Bud (Harry Dean Stanton), who offers him twenty-five bucks to drive his wife's '78 Oldsmobile Cutlass out of "this bad neighbourhood."

Otto's first clue that Bud's lying is when an angry Hispanic man in his pyjamas runs out of a nearby apartment to stop him as he drives away. His next clue is when he follows Bud's car into the yard of the Helping Hand Acceptance Corporation, where he learns that Bud is a repo man, and that he's become one as well, after repoing his first car.

Otto rebuffs the offer of a job until he comes home and learns that his burnout ex-hippie parents, who sit in front of their TV all day smoking pot and watching TV, have given the thousand bucks they promised him if he finished school to a televangelist, to send "bibles to El Salvador." This sends him back to the Helping Hand yard, and his repo apprenticeship.

Riding around with Bud in his '71 Chevy Impala, Otto learns that the repo man has a code, prime among which is the imperative not to harm the car he's repossessing or its contents – a bit that Cox took from Isaac Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics and Harry Dean Stanton's constant improvisations. Bud also teaches him to dress like a detective so people think he's carrying, that a repo man is always on the job, ready to drive, and unlike the average citizen seeks out tense situations.

"Hey – look at those assholes over there," Bud says to Otto, watching a group of people argue with a tow truck as it hauls a car away. "Ordinary fucking people. I hate 'em."

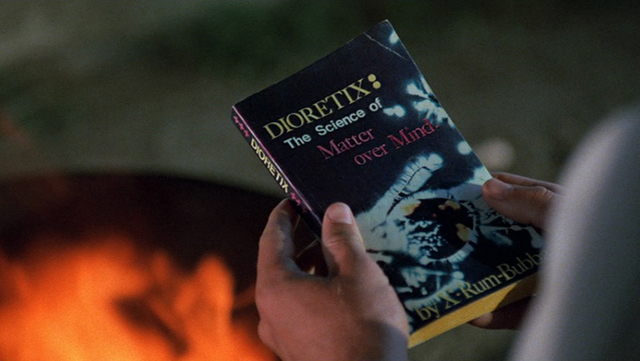

He also tags along with Lite (Sy Richardson) in his '73 Ford Ranchero. (All of the repo men at Helping Hand are named after beers.) Lite is more of a badass – he doesn't respect the cars he repos or their contents, and carries around the tools to break into and hot wire a car in his briefcase, along with a shiny M1911A1 that Lite casually fires into a house when a repo goes wrong, later revealing that it's loaded with blanks. He insists that Otto read his copy of Dioretix – an obvious spoof of Scientology that Lite claims will "change your life".

The least obviously useful advice Otto gets is from Miller (instantly recognizable character actor Tracey Walter), the Helping Hand's burnout mechanic and janitor. Miller is full of theories about cosmic coincidence and why people have suddenly become obsessed with the Bermuda Triangle, UFOs and "the Mayans inventing television." He tells Otto that people are disappearing every day, and wonders how the world got so quickly populated with humans. The answer, of course, is that UFOs are time machines.

"Did you do a lot of acid back in the hippie days, Miller?" Otto asks.

Some people might call the nihilism and crackpot philosophy of Helping Hand's repo men exaggerated for comic effect, but what struck me watching the film back in the mid-'80s – a white suburban punk working a series of dead-end minimum wage jobs as a dishwasher, fry cook and security guard – was how it echoed the furtive, poorly-articulated advice I was always getting from the older men I met on the job.

The '70s had seen a flood of pop culture speculation about the paranormal and supernatural flood into the mainstream along with televangelism, new age philosophy and quack medicine, after the social revolution of the '60s had blown huge chunks out of the walls protecting the authority of establishment science, religion and political authority. A young man of no means and indifferent education was forced to take everything at face value, especially when the old authorities hadn't provided answers that worked – or sold them with confidence.

Cox had initially imagined Repo Man as a road movie, but when the budget got smaller the film tightened its scope to downtown L.A., far from the mountains and beaches, with the Los Angeles River – a shallow stream trapped in its wide concrete embankments – being the only body of water we see. But it remained a car movie, with much of the action happening in and around the collection of mostly '70s gas guzzlers driven or stolen by the repo men. The last movie that imagined L.A. as a city built for cars first, people second, was the original Gone in Sixty Seconds (1974), and the only one that superseded this autocentric vision of the world would be Pixar's Cars (2006).

At the end of his ramblings, Miller says one thing that Otto can't dismiss as acid-damaged brain leakage. He says that he has his best thoughts when he's on public transit, and that's why he doesn't want to drive. Otto reminds Miller that he can't drive – he doesn't even have a license. Miller says he doesn't want to learn.

"The more you drive, the less intelligent you are."

Like Miller, I never learned how to drive, and while it's a decision I've come to regret, I had (what seemed to me) good reasons at the time. I grew up like any working class kid reading hot rod magazines and checking out cars, but when it came time to get a license I knew that there was no way I'd be able to afford one of my own – not as a budding white suburban punk, and not even as whatever I became after that which, I was sure, wouldn't involve a big paycheque. Better to avoid the temptation and never take the first step, which would have been hard enough living with a widowed, non-driving mother, the garage empty since my father died and we sold the Buick. Which is why Miller's quote – which might still be true – resonated with me back in 1985.

There was no way Repo Man wasn't going to be a slam dunk for me. My favorite movie up till then was Apocalypse Now (1979), starring Emilio Estevez's father, Martin Sheen. By the time I saw Otto onscreen, I could recite whole stretches of dialogue from the Coppola film by heart; it wasn't hard to regard Cox's film as a sequel to Apocalypse Now, with Otto as the son Sheen's Willard left behind Stateside, growing up with his mom and hippie stepdad. What seemed profound in Coppola's picture had become farcical in Cox's – exactly how the natural progression of ideas seemed to this white suburban punk. By the time 1985 was over Repo Man would join Apocalypse Now on the short list of films I'd have watched on acid.

Repo Man gets trippy when the story catches up with the man in the Chevy Malibu. J. Frank Parnell (Fox Harris) apparently has some dead aliens in the trunk, stolen from a military installation in New Mexico, and is trying to hook up with Leila (Olivia Barash), a member of a paranormal cell called the United Fruitcake Outlet, while evading government agents with identical blonde hair and AMC Matadors. Otto ends up hooking up with Leila first, which doesn't stop her from helping the agents torture Otto after they're both captured.

Everyone in L.A. is looking for the Malibu after a $20,000 reward is put out for it, from the repo men at Helping Hand to the car thief Hermanos Rodriguez to the televangelist who got Otto's money. The car passes from hand to hand – the Rodriguez brothers lose it to Otto's old pals Duke, Debi and Archie (Miguel Sandoval), now a punk gang on a crime spree, before Parnell gets it back. Otto ends up in the Malibu with a dying Parnell, who delivers a scene-stealing comic rant about how radiation has an undeserved bad rep, and how he gave himself a lobotomy to deal with the moral torture of working on the neutron bomb. Otto brings it back to the Helping Hand yard where it's stolen again, now glowing bright green.

Like any good farce, the last scene brings all the players back together for a final reckoning, as the Malibu is now spitting lightning and rejecting all attempts to claim it. (Keep an eye out for Mike Nesmith as a Hassidic rabbi, backing up the televangelist alongside a Catholic priest; it's the sort of religious satire that was still considered biting back then.) The only person able to approach the car is Miller, who slides behind the wheel and beckons Otto for a joyride. The car ascends into the night sky over L.A., wheeling around the office towers before punching out into space with a roll of kettledrums, evoking 2001: A Space Odyssey, another pinnacle of stoner cinema.

Nobody expected Repo Man to succeed; Barash's agent warned her to stay away from the project, though Stanton's agent tried to dissuade Cox from casting him as Bud in favor of Mick Jagger (of all people). The studio executive who signed Cox and his partners to their deal now long gone from Universal, the film was barely released into cinemas. A rave review by Roger Ebert and an audience of punks like me helped it make its budget back and launch it onto the cult circuit.

Punks would also make the soundtrack album a hit, loaded as it was with "hits" by bands like Fear, Black Flag, Suicidal Tendencies and the Circle Jerks as well as Iggy Pop's theme song and songs written for the film by Latino punks The Plugz. It was, after all, a great way to collect a whole bunch of great songs on one record at a bargain price – a deal few white suburban punks could afford to overlook. It even included the "lounge" version of "When the Shit Hits the Fan" performed onscreen by the Circle Jerks – the band Otto complains that he used to like. (Keep your eyes peeled for legendary L.A. DJ Rodney Bingenheimer as the owner of the club.)

There are camp elements and cheesy plot twists all over Repo Man, and like Phantom of the Paradise, another cult picture, released a decade earlier and reviewed here recently, they might have relegated the film to "so bad it's good" status if not for the abundant talent working on the project. Cox was a director with some taste, and it helped that he was able to ask for and get the cinematographer of his dreams – Robby Müller, famous mostly for working with Wim Wenders, and later as Director of Photography for William Friedkin, Barbet Schroeder, Jim Jarmusch, Michelangelo Antonioni, Sally Potter, Michael Winterbottom and Lars von Trier.

Müller's camera is never nervous or unsure about where it should be; he would argue with Cox endlessly about his choice to shoot wide, locked off on a tripod, avoiding "coverage" of dialogue that would tempt an editor to produce a more frenetic picture. Harry Dean Stanton also gave Cox a lot of trouble on set, but his Bud is just one of a career's worth of riveting performances, as he gradually falls apart over the course of the picture.

Punk fans and a punk milieu meant Repo Man got called a "punk film," and Cox by implication a "punk director", which led to his next film, the wildly unsatisfying biopic Sid & Nancy (1986). His career after that would be uneven, ranging from Straight To Hell, a spaghetti western tribute, and Walker, an oddball period picture about an American who takes over Nicaragua in a military coup – both released in 1987 – to work on the screenplay for Terry Gilliam's Fear And Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) to Revengers Tragedy (2002) and Tombstone Rashomon (2017), all work that's interesting if nowhere near as enjoyable as his first film.

After years of trying to produce a sequel to Repo Man, with a script titled Waldo's Hawaiian Holiday, Cox made Repo Chick in 2009, a super low budget "microfeature" described as a "spiritual sequel", with a female hero, a plot involving eco-terrorists and stolen nukes, shot in front of green screens and featuring cameos by actors from the earlier film, including Schloss, Balgobin, Barash and Sandoval. Reviews weren't enthusiastic, and Universal responded with a cease and desist order on Cox in advance of their own film Repo Men (2010), an action picture starring Jude Law that had nothing to do with the 1984 picture.

Most people writing about Repo Man today place it firmly in the context of films reacting to and protesting "Reagan's America", not without justification considering Cox's leftist politics. (One of the unfilmed endings of the picture had Otto head to Central America in the Malibu with a stolen nuke to join the freedom fighters).

I was never able to pin whatever was going wrong in the '80s on any particular party, and even a band like the Dead Kennedys, the most political of punk acts at the time, railed against Democrat governor Jerry Brown's liberal hippie fascists enforcing social and ideological conformity in one of their biggest hits, "California Über Alles." (I can't help but imagine that DK singer Jello Biafra voted for Brown when he ran and won again in 2011. I know that people with the DKs on their Apple Music playlists did.)

Downtown L.A. as depicted in Repo Man is an urban dystopia, decrepit and depressing, its sidewalks covered in winos and bodies in rags. I can't speak with any authority that it was really this dire in the '80s – films like Repo Man loved to depict, even celebrate, the griminess and decadence of cities – but it definitely looks that way today, with huge homeless camps covering sidewalks, parks and freeway off ramps all over the city, a real urban dystopia afflicting several California cities, after literally decades of Democrats in power at state, county and municipal levels.

There's no point drawing obvious conclusions, except to quote Otto, near the end of the picture, as the whole story of Repo Man is flying off in every direction:

"Some weird f--king shit, eh Bud?

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.