Zulu is the sort of film that it's become imprudent, even inadvisable, to write about. Nearly six decades since it was released, its subject matter – a battle between white colonial troops and an African army – would certainly never be attempted by a filmmaker today, and certainly not in the same manner as it was in 1964, which it's worth remembering is as far away from us today as the Civil War was from the first stirrings of the Roaring Twenties.

(These temporal comparisons are facile, to be sure, though we've certainly seen as radical a social transformation in the last six decades as the stunning technological changes that happened between the presidencies of Lincoln and Coolidge.)

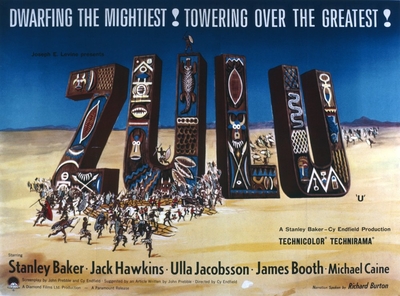

When it was released, Zulu was billed as a spectacle, an epic action picture that delivered the sort of widescreen thrills that television was two generations from capably providing. Even then, it was made at probably the last plausible moment for this sort of unironic celebration of valour by British redcoats on a foreign field; Tony Richardson's The Charge of the Light Brigade, released just four years later, would cast a far more acerbic eye on another celebrated instance of Victorian military bravery, reflecting the cultural sea change that had happened on either side of the '60s.

Zulu retells the story of the Battle of Rorke's Drift, which was fought from January 22-23, 1879, between a tiny British garrison of just over a hundred men and a Zulu army that outnumbered them nearly forty to one. It might not have been memorialized in film nearly a century later if it had not happened just hours after the worst British battlefield defeat until the next century's world wars, at the hands of a native army wielding mostly spears and shields against professional soldiers with rifles, cannon and rockets.

The film was directed by Cy Endfield, an American escaping the blacklist in Britain, based on a script co-written by Endfield and John Prebble, and inspired by an article Prebble had written for Lilliput magazine. It was produced by Endfield and actor Stanley Baker, who plays Lt. John Chard of the Royal Engineers, commander of the defense of the supply depot at Rorke's Drift, a former trading post turned mission station near the bank of the Buffalo River in Natal Province.

The film was meant to be a star vehicle for Baker, but he would be forced to share screen time – and ultimately stand in the shadow – of his co-star, a young cockney actor from London's named Michael Caine.

Caine plays Lt. Gonville Bromhead of the 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot, an aristocratic officer from an illustrious military family who should have been in command of his men at Rorke's Drift except that Chard had got his commission before him. (In the film there's just three months between their commission dates; in real life it was closer to three years, among the smallest and one of many liberties Prebble and Endfield's script took with the facts.)

The film is at pains to introduce us to Chard and Bromhead as very different men. It's implied that Baker's Chard is from the middle classes; his work ethic and aversion to pulling the privileges of rank contrasts with Bromhead, who we first meet on his horse as he returns from a spot of hunting in the hills around the mission station, languidly implying that Chard seems rather unkempt as he mucks in with the men building a pontoon bridge across the river. Chard later grumbles that Bromhead is "someone's son and heir...who got his commission before he learned to shave."

Bromhead's father was in fact a baronet and general who had fought with Wellington at Waterloo, and Caine adds that his great-grandfather was "the Johnny" who was at Wolfe's side when he was killed at Quebec. The army that Britain sent to protect its interests in would become South Africa was still stuck in the long, reluctant process of reform after the notorious failures of leadership and logistics during the Crimean War. It no longer allowed rich men to buy officer's commissions for their sons, but it was led by a man, Lt. General Augustus Thesiger, Baron Chelmsford, whose father most certainly had.

It was Caine's first starring role, and he would later insist that he would never have got the role of Bromhead if Endfield had been English – the class system in Britain was such that as soon as he opened his mouth no producer or director born there would have dreamed of casting someone so obviously working class as an officer in Britain's Victorian military. To be fair, you can see why they would; as charismatic as Caine is onscreen, he definitely seems to be playacting as a toff, especially in his early scenes with Baker, where he lazily bats at his shoulders with a horsehair fly whisk.

Chelmsford, along with Sir Bartle Frere, governor of the Cape colony, was the man responsible for both the desperate defense of Rorke's Drift by Chard and Bromhead's men and for the slaughter that preceded it – the killing of nearly two thousand British soldiers, native auxiliaries and civilians at the camp at Isandlwana by the Zulu army – or impi – of King Cetshwayo.

While the official policy of the British government and Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was to avoid expanding their small colonies and protectorates in South Africa and antagonizing Cetshwayo and the Zulu Nation, Chelmsford and Frere (and influential factions in the Colonial Office) had very different plans, and moved forward with their scheme to invade and annex Zululand before news of their offensive and orders to cease and desist could make their way to and back from London – a process that would take between twenty and forty days.

Chelmsford in particular, who was much favoured by Queen Victoria, was eager to present a victory in Zululand to his sovereign as a fait accompli. The Queen, a constitutional monarch though one with far more political influence than her descendent on the throne today, would be a major player in defending Chelmsford's reputation even after the disaster at Isandlwana. The Zulu campaign as conceived by Frere and Chelmsford would become the tail that would wag Parliament's dog, and Disraeli would be forced to publicly defend it despite his adamant opposition, both personally and before news of the invasion reached England.

The film begins in a military kraal in Zululand, where King Cetshwayo (Mangosuthu Buthelezi, in real life a South African politician and Cetshwayo's great-grandson) is presiding over a celebration – the mass wedding of hundreds of his warriors to their topless brides. His guest of honour is Otto Witt (Jack Hawkins), a Swedish missionary, and his daughter Margareta (Ulla Jacobsson). Witt considers Cetshwayo a member of his parish, and looks on the chanting and dancing with undisguised awe, though his daughter – only recently arrived in Africa – is more prudishly disapproving.

"They are a great people, daughter," says the missionary, chiding his daughter for being quick to judgment.

The Zulu were a recent nation, but a powerful player in southern Africa. They had been forged out of countless warring tribes earlier in the century by Shaka, Cetshwayo's half-uncle, thanks to Shaka's creation of disciplined regiments that extracted labour and military service out of the nation's young men, in exchange for rights to land, cattle and marriage. Descriptions of the Zulu at their height inevitably compare them to Sparta – an austere, warrior people who respect honour and bravery, but a constant threat to their neighbours, which by this point had come to include white Boer settlers in addition to other tribes.

In the middle of the ceremony a messenger arrives with news of the Zulu victory at Isandlwana; Witt and his daughter slip out of the kraal and head for their mission at Rorke's Drift, under the protection of Cetshwayo, their buggy racing down a dusty track past ranks of Zulu warriors, watching silently in the tall grass.

Back at Rorke's Drift, which lies on the path of retreat from Isandlwana, we're introduced to the men of the 24th, starting with Col. Sgt. Bourne (Nigel Green), who embodies the virtues of the noncommissioned officer every army is built upon, more than any lieutenant, captain, major or colonel. Ramrod straight, with an impressive moustache and impassive demeanor, he can quote scripture back at the pacifist Witt, who insists to Chard and Bromhead that they should evacuate the wounded immediately and abandon the post before Cetshwayo's impi arrives.

There was indeed an Otto Witt at Rorke's Drift, a missionary but not a widower, with several young children who had already left for safety when he put the mission station at the disposal of Chelmsford's army. He was not, however, a militant pacifist or (as far as we know) an alcoholic. Hawkins chews ever more yards of scenery as the soldiers prepare for a siege and withstand the first Zulu attacks. He encourages the African auxiliaries and soldiers of the Natal Native Contingent to desert (this happened, though not at Witt's instigation) and whispers to a nervous young soldier that he shouldn't disobey God's sixth commandment, before being shamed into silence by Bourne.

Witt, overcome by drink, is finally bundled off into his buggy with his daughter and ordered to escape the station, but not before Hawkins delivers one final hammy flourish:

"Death awaits you! You have made a covenant with death and hell awaits you! You're all going to DIE! DIE!"

Everyone with a speaking part has a role in creating tension as the Zulu impi approaches. In the hospital there's Cpl. Schiess (Dickie Owen) of the NNC; Swiss-born, he had fought with the French against the Prussians before emigrating to Africa. Blisters had put him in the hospital, where he listens to British soldiers disparaging the Zulu as "savages." He takes exception, telling them that while they might be able to march for fifteen miles a day, the Zulu can run that distance without eating or drinking and assemble for battle immediately.

In the story told by Zulu, Chard and Bromhead's defense of the station would not have been possible without the counsel of Lt. Adendorff (Gert van den Bergh) of the NNC, a survivor of Isandlwana who opts to stay and help. A Boer – he jokes that, at least at this moment, they're fighting together – he speaks isiZulu and understands Shaka's classic battle plan, the "Horns of the Bull Buffalo", a pincer encirclement that he helpfully draws out in the dirt for the British officers.

There was a Lt. Adendorff at Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift, but according to Saul David's recent book Zulu: The Heroism and Tragedy of the Zulu War of 1879, he was a dodgy character who probably fled the action at Isandlwana and made an equally swift exit from Rorke's Drift. Van den Bergh's Adendorff is nearly as much a hero as Chard or Bromhead, and his character is vital to a key scene near the film's climax; the real man's dubious part in the day's battles ended up providing a useful tool for Prebble and Endfield's story.

One soldier given short shrift by both official histories and Endfield's movie is Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton, played by Dennis Folbigge. Accounts by witnesses to the battle describe his role as crucial; he discouraged Chard from attempting to retreat from the station when the senior officer was wavering, and he was key in coming up with plans to fortify the position with firing positions built from the stock of biscuit boxes and mealy bags in his charge.

Zulu alights on him briefly, an officious bureaucrat unable to grasp the threat, like the quartermaster in Zulu Dawn, the prequel Endfield made in 1979, denying precious ammunition to runners from the wrong companies at Isandlwana. Dalton's role has only reemerged in recent years, decades after Chard and Bromhead were lionized in official reports.

In his book Zulu, Saul David notes that when the battle was over, Chard toasted his survival with a bottle of beer he shared with Bromhead. "He might have offered a sip to Commissary Dalton, the man who more than any other had organized and inspired the defense. But he did not. Dalton had come up from the ranks; he also knew too much."

Probably the greatest liberty the script takes with real life is the part of Pvt. Hook (James Booth), who we meet in the hospital where he's malingering while under house arrest. The man is a bully, and Bromhead describes him as a "thief, a coward and an insubordinate barrack room lawyer" while upbraiding Chard for giving him a rifle to defend the building.

He overcomes his sullen indolence seeing his friends' lives are in danger and not when ordered by any officer or sergeant, and heroically saves them when the Zulus attack the hospital and set it on fire. James Booth's Hook has the same hostility to authority older audiences would associate with spivs and wide boys, but a younger generation would recognize the angry young man – the rebel kicking against the system, without a clear objective of his own. It was actually the role Michael Caine was being considered for when Endfield was inspired to cast him as Bromhead, having already chosen Caine's friend Booth to play Hook.

Just as the real Bourne was a short man, and much younger than the imposing middle-aged NCO played by Nigel Green, the real Hook was a teetotaler and a lay preacher with a distinguished service record, working in the hospital as a cook. Hook's daughter was alive when the film was released, and walked out of the premiere in protest.

Even in a film as widescreen as Zulu, focus is crucial, and the bulk of the heroics and character development has to rest on the shoulders of Baker and Caine. Their adversarial relationship starts to fall away early in the battle, when Bromhead tells Chard about his illustrious father and great-grandfather. It's not because he wants to brag or assert his status, he explains, but because he wants him to understand that, at a moment like this, he wishes he "was a damned ranker like Hook."

Ultimately Zulu builds up to one, legendary scene. The men have held out against attack after attack, each one chipping at their defenses and reducing their ranks. Under a blistering overhead sun (most of the battle at Rorke's Drift really happened in the evening or at night) they brace for a final assault while the impi begins another round of chants that signal an imminent charge.

From the opening scene at Cetshwayo's kraal, the movie has been soundtracked either by John Barry's score or the sonorous, vast chorus of the Zulu warriors, singing in call and response with their officers and sergeants, punctuating the chants by rhythmically beating their assegais against their cowhide shields. It's both ritual and psychological warfare, and it gives the audience a taste of the dread that would overcome anyone facing the Zulu in battle.

Part of the legend of Rorke's Drift is that the 24th was a Welsh regiment, their desperate stand a Welsh story as much as a British one. (Baker was Welsh, and no less than Richard Burton provides voiceover narration at the beginning and end of the film.) It's only partially true – the 2nd Warwickshire had moved their regimental headquarters to Brecon in 1873, and they would be renamed the South Wales Borderers two years later, but at Rorke's Drift only a quarter of the men were Welsh, despite the abundance of Joneses in the ranks. Zulu waves that all aside, and early in the film we're introduced to Private Owen (Ivor Emmanuel), who seems more preoccupied with the company choir than soldiering.

It's the stereotypical Welshman played for light comic relief – good-natured, a little simple, and obsessed with choral singing. But we realize why he's been given such a prominent role when the men are staring over the walls of mealy bags, preparing for the Zulu charge, their terror rising with each booming chorus echoing off the hills from the Zulu lines.

Chard makes his way to Owen and asks him if he "thinks the Welsh can't do better." Owen has nothing but praise for the Zulu bass section, but says they have "no top tenors," then begins to sing "Men of Harlech."

Any Welshman alive at the time would have known the song, commemorating the siege of Harlech Castle by Lancastrian forces during the War of the Roses. (Cinemagoers would remember it from John Ford's How Green Was My Valley.) You can call it a march or a battle hymn or an anthem, and even slightly rewritten by Barry for the film, the lyrics brim with the defiance that might send any man to his death with resolve:

Men of Harlech, stop your dreaming,

Can't you see their spear points gleaming?

See their warrior pennants streaming,

To this battle field!

Owen begins the verse and the men join in, the two choruses forming a duet in the air over the battlefield. It's a marvellous, thrilling, cinematic moment, cut short only when the Zulu impi begin their charge, which breaks against the ranks of redcoats, three abreast at the last line of defense, pouring on volley fire. When they finally stop the men are in shock, standing in front of piles of dead and dying Zulu.

In the aftermath of the battle Bromhead and Chard are surveying the damage while Bourne calls the roll, noting every dead or wounded man. Just then the impi appears again on the hills surrounding them, beginning another chant. The men despair that they're being taunted before a final annihilation. (In real life, the men at Rorke's Drift were almost out of ammunition after the final Zulu attack; one more would have wiped them out.)

Adendorff begins laughing and tells them they couldn't be more wrong. "They're saluting you," he explains. "They're saluting fellow braves." With that the impi raise their shields and turn to leave the battlefield.

It's a marvellous moment, but like the defiant singing of "Men of Harlech", it never happened. The truth is that the Zulu impi wasn't even supposed to be there in the first place; Cetshwayo had ordered his men not to pursue the British troops over the river into Natal, but the regiments under the command of his son, which had been held in reserve at Isandlwana, were hungry for action and plunder. They only left the battlefield when Chelmsford's relief column came into sight.

Critics of Zulu say that the impi and the Zulu people except for Cetshwayo are depicted as a faceless horde. That might be true, but you can also argue that nearly every character with a voice is only there to advance the plot, especially as many of them are presented quite in contradiction of the actual facts of their real life counterpart.

Ultimately only Chard and Bromhead, and really only Bromhead are transformed by the end of the picture. The impi might be a faceless horde, but Prebble and Endfield's story is at pains to celebrate them as a brave and honourable faceless horde, a free people defending their homeland, and ultimately destined to lose. Standing among the bodies, Bromhead confesses to Chard that he felt two emotions after his first battle: fear and shame.

South Africa would become the colony forced on Britain by scheming and obligation, and you can argue that the curse of this improbable country is to never have a workable government. Conflict would be hard wired into its existence, and the next twenty years would see not one but two Boer Wars, with "damned rankers" like my grandfather shipped off from the dockside tenements of Merseyside to fight there, in khaki instead of red coats.

Rorke's Drift was a gift for Chelmsford – a heroic victory to set against the slaughter that preceded it at Isandlwana by mere hours. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded to the men of the 24th, the most ever given to a single regiment for a single action. Many of the recipients ended their days in madness, suicide and poverty, however, and one of them would be forced to pawn his VC.

Bromhead died of enteric fever serving in Allahabad, India in 1891; Chard died of cancer in 1897, just after being promoted to colonel. The Zulus would lose the war and King Cetshwayo would be deposed, living in exile in Cape Town and London before returning to Zululand and dying of a heart attack there in 1884, his kingdom torn apart by civil war.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.