When it came out in 1973, Robert Altman's movie version of Raymond Chandler's 1953 novel The Long Goodbye met a polarizing response, went through two marketing campaigns and still didn't manage to pick up an audience. It might have had to do with how you felt about Altman or Chandler; what's amazing is how many people still had strong feelings about Chandler, twenty years after the publication of his last novel, and nearly fifteen years after his death.

What they might have had strong feelings about was Chandler's hero, private detective Philip Marlowe. Altman threw a curveball by casting Elliott Gould as Marlowe, and setting the story in the present day – and by present I mean the year of the Yom Kippur War, the Roe v. Wade ruling, the Paris Peace Accords, Secretariat, the start of the Watergate hearings, the first US auto plant closures, the Three-Day Week in the UK and the start of the oil crisis.

It wasn't like setting the film in postwar Los Angeles wasn't an option. The movies were in the middle of a major nostalgia trend – American Graffiti opened to huge box office success that year, and two years later Robert Mitchum would star as Marlowe in a period-perfect adaptation of Farewell, My Lovely. Altman himself was never allergic to period pictures – he'd made his offbeat western, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, two years earlier, and would head to the past again with pictures like Buffalo Bill and the Indians (1976), Vincent & Theo (1990), Kansas City (1996) and Gosford Park (2001).

(Let's not pretend that M*A*S*H was a period film, though – despite being set during the Korean War, it's plainly about Vietnam, and the setting is a misdirection that nobody who watched it took seriously.)

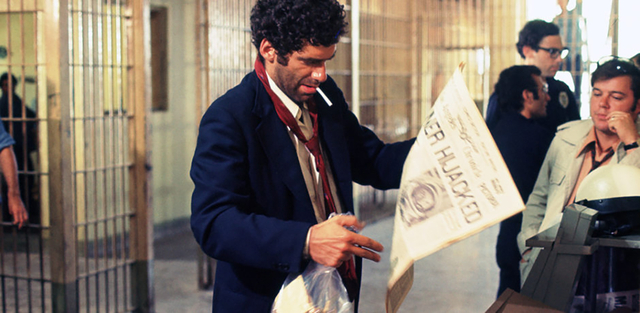

Ultimately, though, what set people off was casting Elliott Gould as Marlowe, even more than Dashiell Hammett's Sam Spade or Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer the quintessential hard-boiled gumshoe. Gould wasn't an obvious choice to anyone except Altman. In a kind review, the Hollywood Reporter described Gould's Marlowe as "wistfully human" and a "tolerantly benign anachronism." In the New York Times, Vincent Canby summed up Gould's Marlowe as "a child of the sixties and seventies."

"His toughness, which is questionable," Canby wrote, "is not born of attempts to survive the Depression, but of an attempt to control feelings, which well could have been ravaged by growing up alternately committed and disappointed by the events of the last 10 years. He's bright, hip, sardonic and, as someone says of him in the film, a born loser."

These are among the raves the film received; Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave it a lukewarm three stars but later changed his mind, upgrading it when he put it on his list of Great Movies in 2006. The really bad reviews tend to regard Gould's Marlowe as a "grotesque parody," but as Altman himself said years later, "what they were really saying was that's not Humphrey Bogart."

The white coat grinned at me. "Okay, sucker. If it was me, I'd just drop him in the gutter and keep going. Them booze hounds just make a man a lot of trouble for no fun. I got a philosophy about them things. The way the competition is nowadays a guy has to save his strength to protect hisself in clinches."

"I can see you've made a big success out of it," I said.

He looked puzzled and then he started to get mad, but by that time I was in the car and moving.

He was partly right, of course. Terry Lennox made me plenty of trouble. But after all that's my line of work.

- Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye

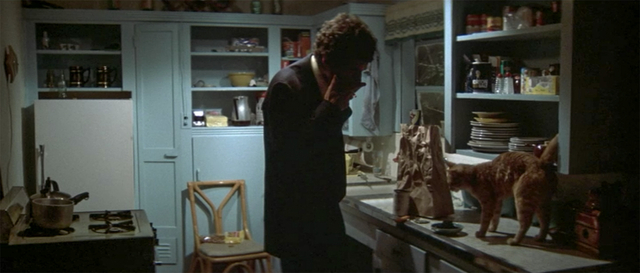

Chandler's novel begins with Marlowe meeting Terry Lennox, but Altman's film begins with Marlowe and his cat. More to the point it begins with Gould waking up, fully dressed, in his apartment in the Hollywood Hills. What follows is a long bit of business where he tries to feed his ginger tabby (the original Morris the Cat, finicky feline face of the 9 Lives cat food brand) and fails, with the cat leaving him for good.

According to Altman his Marlowe, roused from a deep sleep, is "Rip Van Marlowe" – the detective woken from a two-decade slumber and forced to navigate Los Angeles in the early '70s, a "very weird time...glazed in a haze of pot smoke." His neighbour on the top floor of the Art Deco landmark High Tower apartments near the Hollywood Bowl when he fell asleep would have been an alcoholic, over-the-hill ingénue, kept by a studio boss, but when he wakes up it's a commune of topless young women who run a hand-dipped candle shop, but otherwise spend their days doing yoga and making hash brownies.

(In 2014 the apartment, designed by architect Carl Kay and built in 1920, was up for rent at $2800 a month; former tenants included writer Michael Connelly and magician David Copperfield.)

By the time he meets his friend Terry Lennox (former Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton, retired after publishing his scandalously frank book Ball Four) we're accustomed to his mannerisms and tics, like his constant chain smoking (Marlboros and Lucky Strikes, lit with magic matches that he strikes on nearly any convenient surface), his loping walk and his mantra – "It's okay with me," the bemused, droll attitude of Bogart's Marlowe in The Big Sleep distilled down to an "I'm OK, you're OK" shrug for the new decade.

Gould's Marlowe might look more like a former college radical forced into a cheap dark suit to make an altogether precarious living, but Altman strives to portray him as a man out of time, from his apartment – set-dressed with the sort of dusty bric-a-brac a private detective might have collected during the Truman administration – to his car – a 1948 Lincoln Continental Cabriolet (actually Gould's own car) – to the way he calls a stray dog blocking the road "Asta", as if he couldn't think of a dog's name after the Thin Man films.

And despite the topless yoga and the massive afro on the guy working checkout at the all-night grocery store and the bell bottoms and flowing dresses, there's still a lot about the Los Angeles of 1973 that Chandler's Marlowe would have recognized. There's his pal Terry, for instance – a guy mixed up in some nasty business, who needs Marlowe to drive him to the border at Tijuana so he can go on the lam for a while. By the time Marlowe gets back to his apartment, however, Terry's wanted for murdering his wife and Marlowe is an accessory.

If anyone could be given credit for providing continuity between the Marlowe of Chandler, Howard Hawks and Bogart it would be screenwriter Leigh Brackett. She's best known for her contribution to science fiction; dubbed the "Queen of Space Opera," she labored in the genre when it lived in pulp magazines and paperbacks and only occasionally made its way into serials and b-pictures, though she lived long enough to write a draft of The Empire Strikes Back, which she finished just before her death in 1978.

But the second string to her bow was crime fiction, which saw her work on the screenplay for Hawks' The Big Sleep in 1946 – actually Bogart's only onscreen turn as Marlowe, though it looms over nearly every other movie featuring Chandler's hero, which includes Dick Powell (Murder, My Sweet in 1944), Robert Montgomery (The Lady in the Lake in 1946), George Montgomery (The Brasher Doubloon in 1947) and James Garner (Marlowe in 1969 – probably the closest comparison possible to Altman and Gould's Marlowe, and also set in the present day.)

Brackett wrote the script for The Long Goodbye, and according to Altman gave him her blessing to tweak and update it any way he wanted. If Altman's film manages to stand astride two eras without coyly referencing pop culture or celebrating its own cleverness, the credit can probably begin with Brackett.

By far the cleverest thing the film does involves its theme song, written by Johnny Mercer and John Williams. It's a smoky ballad, not surprising for what's essentially a film noir, with lyrics that are suitably sensual and ominous:

There's a long goodbye

And it happens everyday

When some passerby

Invites your eye

To come her way

We hear it at the start of the film, and in competing versions throughout the film – on the soundtrack, coming from radios, as muzak in a grocery story, played by a bar pianist (Jack Riley, better known as Mr. Carlson on The Bob Newhart Show), as the ring on a doorbell, even played by a marching band at a funeral in a Mexican town.

There's an instrumental version played by the Dave Grusin Trio, and vocal takes by Jack Sheldon – the jazz trumpeter and singer who sang "I'm Just A Bill" for Schoolhouse Rock! – and Clydie King, a veteran singer whose career went back to the '50s, and who sang backup with everyone from Barbara Streisand and Linda Ronstadt to Dylan, the Rolling Stones and Joe Cocker. (It's King, along with Merry Clayton of "Gimme Shelter" fame, who can be heard singing behind Ronnie Van Zandt on Lynyrd Skynyrd's "Sweet Home Alabama.")

As with every other Chandler plot, there's a secondary storyline that ends up twisting back into the first. A brief stint in jail as part of a murder investigation gets him enough column inches in the newspaper to attract a new client – Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt), who wants him to find her husband Roger (Sterling Hayden), a famous writer and neighbour of Marlowe's buddy Terry in the exclusive Malibu Colony. She saw his picture in the papers and, like Gloria Grahame's Laurel in In A Lonely Place, she says she likes his face.

Nina van Pallandt was officially Baroness van Pallandt thanks to her marriage to Frederik, Baron van Pallandt, son of a Dutch baron and a Danish countess. The couple were a singing duo, with calypso-styled hits in Europe, but by the time she caught Altman's eye as a guest on a talk show, she was separated from her husband and famous for being romantically linked to Clifford Irving, author of an infamous fake autobiography of Howard Hughes.

Sterling Hayden would probably have been the biggest star in the picture if his life and career hadn't hit a rough patch – or rather the latest of several, beginning with his decision to join the Communist Party after he'd returned from fighting with partisans in Yugoslavia during the war.

Audiences had seen Hayden in The Godfather the previous year, playing McCluskey, the bent cop, and he'll probably be remembered forever as Gen. Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove. Noir fans who bought tickets for The Long Goodbye remembered him from a series of indelible roles in films like The Asphalt Jungle, Crime Wave, Naked Alibi and The Killing. Hayden had an onscreen intensity that few actors could match, and the blacklist didn't seem to keep him from choice parts even at its peak.

Altman originally cast his friend Dan Blocker (famous for playing Hoss on Bonanza) as Roger Wade, but when the actor died before production began, he was ready to leave the film until somebody suggested that they might get Sterling Hayden for the part. Hayden preferred sailing to acting, however, and had an indifferent relationship to money. Altman recalls watching Hayden, a big man, shuffling down the road to his house in the Malibu Colony in his sandals to meet him. (Altman's house would play the Wade's home in the picture.) They got along, and Altman arranged for the actor to stay in an apartment near his place during filming.

Hayden's Roger Wade is a blustering, macho writer in the Hemingway mode, an alcoholic whose habit is edging into mental illness, suffering from writer's block. Marlowe finds him at a rehab facility run by a quack (Altman regular Henry Gibson) but home clearly isn't the place he should be, based on how his wife flirts with Marlowe, motivated by something she hasn't told him.

A key scene between Gould and Hayden on the beachside patio – though not much is said to advance the plot a much as delineate character – was mostly improvised, while Hayden was drunk and high. The middle part of the film is largely concerned with watching Hayden's Roger fall apart, and the movie finally tips over into the chaos that's been threatened since Marlowe was arrested when the older man walks off into the surf at night and drowns.

The connection between Marlowe's friend Terry and the Wades – we all knew it was there; these plots inevitably circle back into each other in Chandler stories – is made explicit by Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell), the film's heavy, a gangster owed $350,000 by Terry who's intent on collecting it from Marlowe.

Rydell is better known today as a director; he made The Cowboys (1972), the film where John Wayne dies, before directing The Rose (1979) and On Golden Pond (1981). But he was a great actor as well, and his Augustine is an unpredictable psycho, spouting psychobabble about self-realization one minute and exploding into incoherent, paranoid rage the next.

He's so over the top that you're unwilling to take him seriously until a scene in Marlowe's apartment. Instead of staying in his car downstairs, Marty's mistress Jo Ann (Jo Ann Brody) wanders upstairs and asks for a Coke. Finding an opened, flat bottle in Marlowe's ice box, Marty draws Marlowe's attention to the placid, sweet young woman, explaining how much he loves her before he brutally smashes the bottle across her face to show how far he's willing to go to make a point – and get his money back.

It's a brutal moment that shatters the hazy, ambling tone of the film so far, and it calls back to two famous moments from earlier crime pictures – the grapefruit James Cagney pushes into Mae Clarke's face in The Public Enemy (1931), and Gloria Grahame, disfigured by a pot of coffee thrown in her face by her gangster boyfriend in The Big Heat (1953).

(I'd tell you to keep your eyes out for Arnold Schwarzenegger as one of Marty's goons, but you really don't have to look hard – he's pretty easy to spot.)

Altman and cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond work hard to create a distinct look for the film, from the restless camera, constantly zooming and moving, to their solution to shooting in L.A.'s harsh light, where the sun always seems to be hovering overhead. Zsigmond overexposed the film and then flashed it with light before processing, which softened it up considerably, taking the edge off both the shadows and the colour, giving the film a muted palette.

Discussing the technical innovation at the time, Zsigmond explained that "we were making a today picture, but we wanted the look of 20 years ago. It is very difficult to talk about it in words, but we did not want to re-create the '50s, but to remember them. So what we decided to do was to put the picture into pastels, with a shading toward the blue side. Pastels are for memory."

Besides the Mercer and Williams theme, the only other music in the film is a burst of "Hooray for Hollywood," from the 1937 film Hollywood Hotel. It plays over the United Artists logo at the start of the film, and at the end, during the final scene, itself a conspicuous quote from the final scene of Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949), except instead of Nina Van Pallandt's Alida Valli ignoring Elliot Gould's Joseph Cotten, he ignores her as they pass each other walking down a long road colonnaded with trees.

Between the light and camera and music, The Long Goodbye creates a self-contained world for itself, where other crime and noir pictures echo in the action and never seem out of place. It's as if a kind of purgatory was created for Philip Marlowe, where he's resigned to waking up in a different body and a different time, but always facing the same threats and betrayals. Gould's particular Marlowe is such a patsy, never even one step ahead of either his friends or foes, that you wonder if he's even a detective – at least until the end, when he pulls the gun you never suspected he had.

In this light the title – Chandler's best, among a career full of great ones – describes Altman's movie as a long (but never final) goodbye to men like Philip Marlowe, his morality and his times. In 1973, it was probably the only Marlowe you could plausibly imagine.

He turned and walked across the floor and out. I watched the door close. I listened to his steps going away down the imitation marble corridor. After a while they got faint, then they got silent. I kept on listening anyway. What for? Did I want him to stop suddenly and turn and come back and talk me out of the way I felt? Well, he didn't. That was the last I saw of him.

I never saw any of them again – except the cops. No way has yet been invented to say goodbye to them.

- Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye

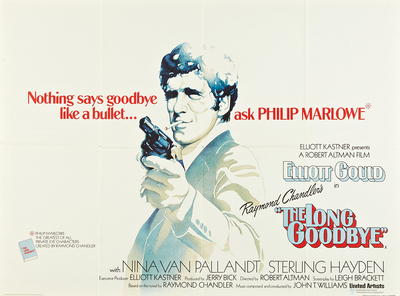

The picture opened to a limited release in cities like Chicago and Los Angeles but did poor business, which Altman blamed on a poster campaign that portrayed Gould's Marlowe as the iconic gun-toting detective at the heart of dynamic action and suspense. This was corrected when the director begged the studio to pull the ads, after which they were replaced by a more comic poster, created by MAD magazine artist Jack Davis, with a caricature of Gould, the cast and the director, featuring speech bubbles sending up the picture for audiences who'd never seen it. It was ultimately an attempt by Altman to manage expectations.

The Long Goodbye is often described – even by Altman himself – as a satire, but if it no longer seems like one it might be because we've been living in a satire of preexisting cultures – social, political, civic – for decades now, and to an endlessly increasing degree. It plays like a period film, as much as anything made when Raymond Chandler was still alive, though it certainly doesn't seem as funny as it did in 1973.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.