There's cold comfort in making a cult film. Most of the time, nobody means to make a cult film – they want a hit, from the moment it's released, and while there might be some satisfaction in seeing your work get praised and develop an audience years, even decades after it was made, there's a very good chance that you never saw much, if any, money. The reward, when it finally comes, is the applause at special screenings, the paid-for hotel and air fare, the personal appearance fees and perhaps some small money to be made from autographs or merchandise.

It's a good thing Brian De Palma has had such a long and high-profile career making films such as Scarface, Carrie, The Untouchables and Mission: Impossible, because it would have been galling if his reputation rested on a horror/satire/rock opera he made in 1974, not long after he'd been kicked off his first major studio picture.

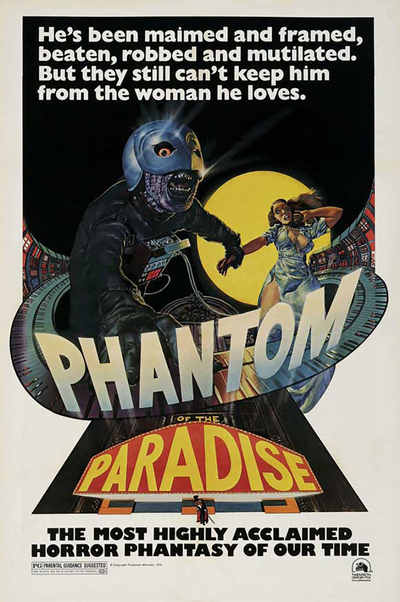

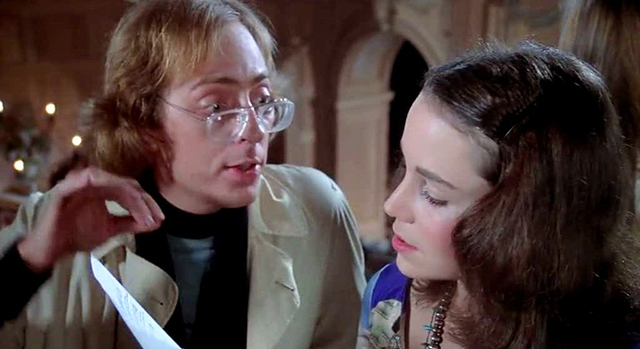

Phantom of the Paradise was, roughly, a rock update to Gaston Leroux' classic novel The Phantom of the Opera, interpolated with the story of Faust, Dorian Gray and a touch of Frankenstein. It's the story of Winslow Leach (William Finley), a talented songwriter who's ripped off and framed by Swan, a famous but reclusive music mogul (Paul Williams). Presumed dead after he escapes from prison, a mutilated Winslow comes back to terrorize Swan and his new music venue, The Paradise, until the impresario tempts him with a promise to produce his music, with Phoenix (Jessica Harper), a young singer Winslow is in love with, as the disfigured songwriter's voice.

The basic story is hardly original, but what makes it stand out from other ambitious, low-budget films often undone by the shortcomings of the script, director or cast, is that everybody involved in De Palma's film was hugely talented. This would also be the saviour of another cult film released the year after Phantom, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, though the latter film would gather its cult around it much more rapidly than De Palma's picture, whose reputation would be slowly built on the audience it attracted in a city on the edge of the Canadian prairie famous for brutal winter winds that carry pedestrians down its main street.

The film begins with a performance by The Juicy Fruits, Swan's latest protégés, singing "Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye," a fond parody by Williams of '50s teen tragedy tunes like "Leader of the Pack", "Teen Angel" and "Tell Laura I Love Her." The trio of actors who play The Juicy Fruits – Archie Hahn, Jeffrey Comanor and Peter Eibling – are at the heart of the film's deep bank of talent, and effortlessly shift gears from greaser rock and roll to surf satire ("Upholstery") as the Beach Bums, and finally to glam as The Undead, wearing Dr. Caligari-inspired makeup and performing theatrical "horror rock," eerily anticipating the imminent rise of KISS, who were doing their first US tour while Phantom was being filmed in New York, L.A. and Texas.

When De Palma was in pre-production for the film, the idea was floated to try and get real acts like Sha Na Na and Alice Cooper for the film, to collaborate on their own satire. They might have managed this casting coup – and produced a much worse film – but Paul Williams, who wrote all the music for the film, opposed the idea, worrying that having the actual artists around would have been inhibiting – not to mention the potential for bruised egos.

Williams began his career as an actor, but his short stature and unconventional looks (he plays one of the town's semiferal teens in Arthur Penn's 1966 southern gothic drama The Chase ) would have relegated him to a subset of character actors, so he began writing songs. "Fill Your Heart," co-written with Biff Rose, appeared on Tiny Tim's 1968 album God Bless You Tiny Tim and was covered by no less than David Bowie on his Hunky Dory album.

By the turn of the decade he was working as a songwriter at A&M Records, where he began a string of hits for Three Dog Night ("An Old Fashioned Love Song"), Helen Reddy ("You and Me Against the World") and especially The Carpenters ("Rainy Days and Mondays", "I Won't Last A Day Without You", "We've Only Just Begun" – the last originally written for a bank commercial.) I remembered Williams mostly for being a constant guest on TV variety and talk shows in the '70s at the height of his career, but barely knew him as a songwriter as much as a witty, often louche personality – a persona he admitted later was facilitated by alcohol and cocaine.

In the earliest stage of production, De Palma suggested Williams play Winslow, but he didn't feel he was up to the physical demands of playing the Phantom, so the director cast him as Swan – a role based at least superficially on producer Phil Spector, the "Tycoon of Teen" behind hits for acts like the Crystals, the Ronettes, the Righteous Brothers and Ike & Tina Turner. Spector, who died in prison last year after being convicted of murdering actress Lana Clarkson in 2003, had already accrued a sinister reputation by the early '70s, thanks to bullying antics in the recording studio, which often involved waving around a gun.

Despite this, Spector was still admired for his artistry and vision and his famous "Wall of Sound", so much so that the Beatles worked with him on their Let It Be album, and both John Lennon and George Harrison would collaborate with Spector on solo projects. He was a maniac and, ultimately, a murderer, but De Palma had to have looked elsewhere for Swan's rapacious, exploitative business sense – somewhere like, say, the whole of the music industry.

De Palma was known for being one of the "film school brats" – a group of young directors in thrall to European auteur cinema; De Palma and Martin Scorsese represented the East Coast wing of this vague movement, with George Lucas and Steven Spielberg on the West Coast and Francis Ford Coppola traveling between the two. He began his career making documentaries and low-budget features whose critical response got him a coveted invitation to leave for Hollywood to make his first major studio picture.

Working with Orson Welles, one of his idols, was the main reason De Palma agreed to direct Get To Know Your Rabbit (1970); working with Tommy Smothers was the reason he end up regretting the decision. The musician and comedian was still riding high after the brief but high profile run of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, and vocally undermined the young director's ideas. The star's resistance to the director ended up with the studio taking the film away from De Palma in the editing suite, and it sat on the shelves for two years before being quietly released to theatres, where it died an uncelebrated death.

De Palma retreated back to New York and independent pictures; he directed and co-wrote Sisters, a psychological thriller starring Margot Kidder, with writer Louisa Rose, and they'd work together again on the first draft of the Phantom script, which was meant as his angry response to his treatment in Hollywood, transposed to the music industry after De Palma heard a Muzak cover of a Beatles tune in an elevator.

If Hollywood could be soul-destroying, the music industry is famous for its relentless, rapacious exploitation of artists. This was as old as the industry itself, and particularly early rock and roll, which was famous for payola and mob ties, and business practices that included giving label owners and producers and even radio DJs songwriting credits, guaranteeing them the lion's share of royalties in perpetuity, at the expense of performers and writers, who would lose the rights to their songs and records with the gift of a car or a single, paltry cash buyout.

(The industry is still based on these exploitative tactics, which have evolved to include lifelong publishing deals, unrecoupable cash advances and "360° deals" where labels get a cut of songwriting, recording, touring and merchandise – basically everything short of an artist's firstborn.)

Swan might have looked like Phil Spector, but his modus operandi – which includes signing artists to legally indefensible lifetime contracts (in blood, no less) – was closer to Allen Klein, a vicious manager and label owner who bore an uncanny resemblance to Philbin (George Memmoli), Swan's thuggish right hand man and fixer.

Klein, who was at near the apex of his power and influence in the music industry at the time, was famous for presenting himself as a musician's advocate, aggressively representing them in negotiations with their management and record companies. He made this reputation with R&B singer Sam Cooke, and by the end of the '60s was managing both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

He entered the Beatles' lives around the same time as Spector, and was particularly favored by John Lennon, despite warnings about Klein's rapacity. Klein and his ABKCO Records would end up owning both the masters and the rights to Sam Cooke's music and the Stones' career up until halfway through Exile on Main Street. He'd end up spending time in jail for tax evasion in 1980; the infamy forced him to take a backseat role in the industry, but he began managing Phil Spector's business affairs in 1988, and died in New York City in 2009.

If De Palma wanted to vent about the injustice of his treatment by Hollywood, he couldn't have chosen a broader, more deserving proxy target. It might have been too broad a target, however, as the proclivities of the record industry were no secret: reviewing the film in the Chicago Tribune, Gene Siskel wrote that "joking about the rock music scene is treacherous, because the rock music scene itself is a joke."

With supreme irony, De Palma would exercise an act of creative betrayal before he shot a foot of film. When producer Ed Pressman approached him, De Palma was desperate to accept his offer and make the film despite what seemed like a lowball offer. Co-writer Louisa Rose wasn't as enthusiastic, so De Palma carefully cut out the work of his collaborator from subsequent scripts.

Swan's relentless, even obsessive betrayal of Winslow and everyone else around him hardly generates suspense, and its fiendish intensity only feels tragic thanks to Paul Williams' score. Williams wrote a gamut of material for Phantom, cycling through doo wop and surf music to singer/songwriter ballads to glam metal, stopping along the way for the ragtime-tinged kind of tune ("Never Thought I'd Get to Meet the Devil", "The Hell of It") he'd made something of a trademark in the '70s.

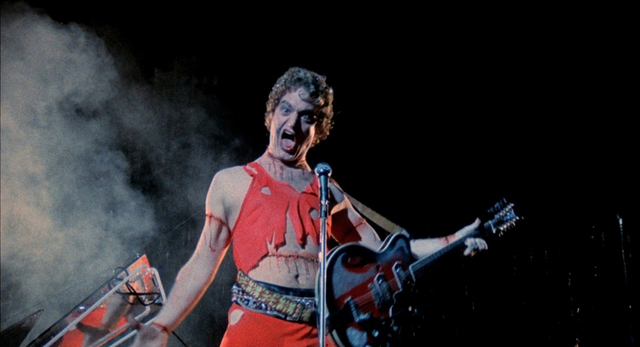

The movie's undisputed masterpiece is "Old Souls," a song we first hear in a rehearsal, after Swan has sequestered Winslow in a hidden studio to finish his song cycle while he sidelines Phoenix in favor of Beef (Gerrit Graham), an outrageously swish glam front man who'd never be allowed onscreen today.

Gerrit's Beef steals the screen as he struggles to sing Winslow's song, complaining that it was "scored for a chick – I'm not doin' it in drag." Swan, who really doesn't have an artistic as much as a marketing vision, encourages Beef to "make it your own," and when we see him onstage next, he's created an over the top, hilarious horror rock character, but his career ends abruptly when the Phantom, enraged at Swan's latest betrayal, sends a neon lightning bolt down from the rafters and electrocutes Beef mid-lyric.

Desperate to keep the show going, Philbin sends Phoenix out in front of the crowd to sing "Old Souls" as Winslow intended. Phantom was Jessica Harper's feature film debut; she'd competed with no less than Linda Ronstadt for the role of Phoenix. With much of the score still unwritten during auditions, De Palma had her sing "Superstar" – the best song by the Carpenters that Williams didn't write. It's ironic that "Old Souls," a haunting, painfully poignant song (Williams likes to call his work "anthems of co-dependency") would end up in a film that so few people would see, when Williams could probably have made it a hit with anyone else.

It's a showstopping moment, which is good, because it has to be if the film is to work at all. Harper's voice, normally soprano, dips down nearly into a low contralto, and she sells the song's melancholy, aching mood beautifully, carving out a calm moment amidst De Palma's frenetic, comic-book style.

Phantom might have had a tiny budget, but De Palma's talent lifted it above the tentative, sometimes overhyped, sometimes plodding direction of too many cult pictures. It moves briskly, and before long we're at the finale – a televised spectacle live from the Paradise, where Swan is set to marry Phoenix before having her shot by a sniper, certain that an assassination broadcast to millions is the greatest kind of show business.

The film's style shifts again, to cinema verité, with multiple cameras and split screens capturing the chaos onstage when Winslow saves Phoenix; the sniper's bullet kills Philbin (officiating in full papal regalia) and thanks to a burning vault of master tapes and multimedia contracts with the Devil, Swan and the Phantom die onstage instead, Phoenix realizing too late what she'd given up for the rush of performing in front of an adoring crowd.

But De Palma depicts that crowd as grotesque. Five years previous, the director had made Dionysius in '69, a documentary about a New York theatre troupe, the Performance Group, doing a Euripides play, influenced by the barrier-busting dramatic theories of theatre gurus like Jerzy Grotowski. Finley had been a member of the troupe, and De Palma hired them to create the anarchic spectacle.

The Performance Group would later fall apart and re-form as the Wooster Group, launching the careers of actors such as Spalding Gray and Willem Dafoe, but the star of the Performance Group as captured by De Palma in 1974 was Will Shepherd, seen as a fan who emerges from the audience with the chaos, inserting himself into the bloodshed, gyrating with abandon and taunting the dying Winslow as he crawls down a ramp into the audience as he dies. With his open shirt, silver belt buckles and blonde bowl cut, Shepherd's unnamed fan forces himself to center stage, the fan becoming the performer, terrifying to behold and, at least for a moment, beyond the control of svengalis like Swan.

Phantom of the Paradise was not a hit. It had been dogged by legal troubles since the start – promoter Bill Graham had forced a name change from Phantom of the Fillmore, Universal Pictures had served notice that it infringed on their ownership of the Phantom of the Opera story, and Kinney Services, owner of a comic book character called The Phantom, had forced a change to the final title. Each speed bump had meant settlements and lost time.

But the hammer blow came after filming was finished, and Led Zeppelin brought suit, claiming that the name of Swan's record company – Swan Song – infringed on the name of their own, newly minted label. Zeppelin's manager, the elephantine Peter Grant, probably the only man in the industry who could intimidate Allen Klein, made the matter personal: earlier in his career he'd managed Stone the Crows, a band whose guitarist died of onstage electrocution, and he thought the death of Beef in De Palma's film was an unforgivable liberty.

Zeppelin's lawsuit meant that De Palma had to go back and either edit out shots where the Swan Song logo was clearly readable, or cover it up with crude mattes and process shots that still look jarring today. It destroyed his careful editing and pacing, and ultimately made the Phantom experience as miserable as his exit from Get To Know Your Rabbit.

It would take De Palma a year or two to recover from Phantom, but in 1976 he cast Sissy Spacek, set dresser on the film and girlfriend of Jack Fisk, the film's production designer, as the lead in his movie adaptation of a Stephen King novel called Carrie. It was the smash hit his career needed, and led to everything that would follow – Dressed to Kill, Blow Out, Scarface, Body Double, Casualties of War, The Bonfire of the Vanities, Carlito's Way, The Black Dahlia and more.

Phantom turned out to be the gift that kept on giving for Paul Williams. He had a huge, lingering hit when he wrote "Rainbow Connection" for Kermit the Frog in 1979, but substance abuse and overexposure put his career into slow eclipse by the '80s. After getting sober in 1990, he found that the cult that accumulated around Phantom would include fans like director Guillermo del Toro, who has been working with him on a musical version of Pan's Labyrinth, and the French techno act Daft Punk, who asked him to write songs with them for their biggest album, Random Access Memories (2013). In 2009 he was elected president of the American Society of Composers and Performers.

Because it was such a flop, screening rights to Phantom of the Paradise were cheap to buy, and my local UHF TV channel, CityTV, seemed to show it every other month by the end of the '70s. The film bombed on release everywhere except two cities – Paris and Winnipeg, Manitoba. Where everywhere else had audiences throwing rice and doing the Time Warp to Rocky Horror, Winnipeg hosted regular screenings of Phantom, helped make the soundtrack album go gold, and ended up being home base for the cult.

Fans like Rod Warkentin saw it nearly thirty times during its initial Winnipeg run, and helped organize the first Phantompalooza in 2004. The next year they managed to get Finley and Gerrit Graham to attend, and in 2006 Williams himself flew to Winnipeg to host the fan convention. For the 40th anniversary of Phantom's release, Phantompalooza moved to Los Angeles and reunited most of the original cast onstage.

2019 saw the release of a documentary about the film's prairie cult, Phantom of Winnipeg, where one fan mused that it might have had to do something with isolation, and long winters. In a 2014 article in Maclean's, Warkentin speculated that the film's appeal for adolescents might have been because "nobody gets what they want."

"No one wins."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.