By the time I started taking movies seriously, A Summer Place had become the sort of film everyone knew about, but nobody – as far as I could tell – watched. The film had been a box office smash in 1959, and the subject of considerable editorializing, but by the turn of the '80s it was a cultural artifact, used to evoke both a "simpler time" (always receding into the past at an apparently fixed distance of roughly a generation) and simmering social tumult on the verge of destroying that simplicity.

The only actual glimpse of the film I'd ever had was in another film – the famous "popcorn scene" in Barry Levinson's Diner (1982). Set during the Christmas holidays just a month after the release of A Summer Place, it's the story of a group of young men in their early twenties uncertainly shifting gears from youth to adulthood. The charismatic centre of the group is Boogie (Mickey Rourke), an uncontested cocksman whose gambling addiction prompts him to bet his friends that he can get his date to touch his penis during a screening of A Summer Place at the local movie theatre.

Boogie resorts to misdirection, unzipping his fly and pushing his member up through the bottom of the popcorn box, which produces the desired result, though his date bolts from the theatre in shock when she realizes that there's more boner than butter in her fingers. He catches up with her in the lobby and shows how smooth he is when he explains that it was an accident: he was turned on by her, and unzipped his fly to allow his johnson to breathe. And then he got "caught back up in the picture, and that's when Sandra got her leg caught on the bush and she lifted up her dress, you know it just popped right up and went through the bottom of the popcorn box."

"It's Ripley's, I'm telling you, it just pushed the flap right open."

The old "popcorn trick": an urban legend that was already in circulation when Levinson was a callow youth. Diner's twist was to link it with A Summer Place – infamous for being sexually overwrought, and the sort of movie that would plausibly inspire helpless tumescence in a young man. In any case Boogie's date buys his cock and bull story and they return to their seats for the rest of the film.

That would be all I'd know about A Summer Place for decades. Well, not really – there's the movie's theme song, released as a single two months before the premiere of the film and a record-breaking, chart-topping hit within a couple of months of the movie's release. But more about that later.

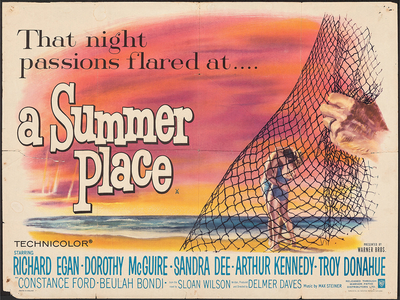

A Summer Place was based on a book by Sloan Wilson, whose novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit captured the zeitgeist four years earlier and got made into a movie starring Gregory Peck. The movie version of A Summer Place would be produced, written and directed by Delmer Daves, whose career highlights up till that point included Destination Tokyo, Dark Passage, 3:10 to Yuma and An Affair to Remember. Daves put a lot of effort into making A Summer Place, expecting to get a big reaction from the picture, and he succeeded.

It's the story of two families. Bart and Sylvia Hunter live with their teenage son Johnny in his family's summer home on Pine Island, one of those exclusive enclaves on the New England coastline, once a haven for old money. Old money became no money, unfortunately, and now Bart (Arthur Kennedy) is a drunk, running his decaying home as an inn.

Their major tenants for the summer are the Jorgensons – Ken and Helen and their daughter Molly; Ken had been a lifeguard on the island before the war, and carried on an affair with Sylvia, who had been persuaded to drop him by her parents in favor of the more socially suitable Bart. Desperate for money, Sylvia persuades her husband to let the Jorgensons rent their own rooms, and they move into the adjacent cottage, once the bunkhouse where Ken had lived.

It seems Sylvia chose poorly; her husband is drunk and poor, but her former boyfriend is now rich and accomplished – a research scientist and millionaire whose aspirant wife has persuaded him to rent a sailing yacht for the summer. Ken's motivations for returning to Pine Island are more basic – he wants to see what's changed, and if he still has feelings for Sylvia; a game of emotional chicken he plays with himself.

What's obvious from the start is that both marriages are on the rocks, and that the best they can manage is to "put up a good front." Richard Egan plays Ken as a man of candour and capability – which translates as virility in Daves' picture, or at least the sort of domesticated virility permitted to middle-aged men. Bart is his polar opposite; Arthur Kennedy gives him a sort of spoiled, bibulous charm, but his frank talk is less candour than lack of consideration. At dinner on their first night on the island, Bart leans into the uptight Helen Jorgenson and muses that "I like to think of the island as a perverted Garden of Eden."

Dorothy McGuire's Sylvia is the noble beauty, suffering the indignity of a disappointing husband by putting all her effort into raising a better son. If the movie has a villain, though, it's Helen Jorgenson. Constance Ford does not play her as either noble or a beauty; the actress was better known for television work on shows like Perry Mason, Father Knows Best, The Phil Silvers Show, Have Gun Will Travel, Rawhide and The Twilight Zone. (In 1967 she would join the cast of the soap Another World, playing the tough, thrice-widowed Ida for a quarter century.) As Helen, Ford's mouth is fixed somewhere between a pout and a sneer, and the most telling judgment Daves' script makes on her is when she casually banishes her husband to the spare bedroom – an exile he doesn't protest.

Ford's Helen is meant to stand in for every negative quality popularly ascribed to America's lumpen middle class by public intellectuals at the time. She's joylessly materialistic, putting on airs and striving to ape her social betters with barely concealed resentment; naturally she's a bigot, but her greatest sin in the eyes of her daughter and husband is that she's "anti-sex" – frigid and prudish and intent on stage-managing her daughter's transition from girl to wife with maximum social and economic benefit to the whole family, the principle task of which is to preserve Molly's virtue at the moment of its premium value.

But the real stars of A Summer Place – at least according to the posters and the public – are Sandra Dee and Troy Donahue as Molly and Johnny. The teenagers are drawn to each other immediately, and the single of the "Theme from A Summer Place" that rose to the top of the charts in the early months of 1960 is actually called the "Molly and Johnny Theme" in Max Steiner's score for the picture. While their families continue that awkward first dinner together, they escape to the garden overlooking the sea where (that rose bush and the lifted skirt) they share their first kiss. It takes Ken and Sylvia a bit longer to revive their own youthful affair – put it down to caution that comes with age – but soon there are two couples sneaking around Pine Island.

I don't have much to say about Dee and Donahue. Over sixty years on, their youthful ardor for each other is a void at the centre of the film; an adult can't help but wince at the way hormones and loneliness sharpen so keenly from the moment they know neither of them are going to say "no" to each other, and Tinder and hook-ups have made every circumstance that surrounds their romance look alien, even absurd, to a young person today. Finally watching the film for this column, I was surprised at how much more I cared about the adults, even if Daves' script draws them with the broadest strokes.

A Summer Place doesn't get written about much anymore, but one scene that stood out for me happens early in the film, after Ken and Sylvia acknowledge their lingering attraction and agree on a rendezvous that night in the boathouse. They've been overheard by Bart's aunt, who summons Sylvia into her room curtly.

Beulah Bondi's Aunt Emily has been, up till this point, snobbish and dotty comic relief – a holdover from the island and the family's better days, who recognizes Ken immediately and insists on referring to him as "lifeguard." When the Jorgensons arrive at the inn where Aunt Emily is an annual guest, she looks over Dee's Molly with a combination of alarm and approval: "Hardly proper to be so pretty. Seems all the nice girls I know have bad skin, are too fat, too thin or have thick ankles."

Sitting down with her niece, she drops the dottiness and offers a frank appraisal of her situation: Bart has committed a sin common to their class and made a virtue of his incompetence, which contrasts as badly with Ken's capabilities as that bad skin and thick ankles do with Molly's much-noted ripe femininity. Aunt Emily might have been raised a snob, but she's close enough to the humbler beginnings of her family's (now-exhausted) fortune to understand that excessive breeding exhausts vitality – a particularly American observation, made in the context of a country founded on an attempt to eschew royalty and aristocracy. Sylvia has made a bad deal, but she still has time to change her own fortune, for the sake of her son if not herself; essentially, Aunt Emily coldly advises Sylvia to leave her nephew for Ken, for everyone's benefit.

It's a startling scene, as if Edith Wharton had suddenly assumed authorship in Sloan Wilson's story, underscoring the illusion of America as a classless society – an inescapable fact that the country, then and now, still has a hard time digesting, mostly because unlike Britain or Europe, class in America is far more mercurial. Alone among A Summer Place's characters, Aunt Emily gets the only unchanging truth; she's no less of a Social Darwinist than Helen, but she's far less crass.

Don't let this moment of insight fool you – A Summer Place is not a great film. It might succeed as kitsch or nostalgia or a guilty pleasure, but it doesn't hold up nearly as well as the best melodrama of the same period, and it's not surprising that younger viewers don't see its appeal. Writing about the film three years ago on her Ticklish Business film blog, critic Kristen Lopez writes that "it doesn't have the panache or the inherent camp quality" of a Douglas Sirk picture:

"While this may have been hot stuff back in the early 60s, it's tired, weird, and downright unlikeable. Each character's worst traits are painted liberally onto their character, and at times I wasn't sure if the 'heroes' were true, or simply the least hateful people."

What it does share with the worst melodrama is dialogue that sounds frankly preposterous; it's as if nobody in the film had ever discussed what was wrong with their lives until the moment the Jorgenson's yacht sailed into view of Pine Island, at which point it would become the only topic of conversation.

Writing about moviegoing as a young person in the '50s in his book Movie Love in the Fifties, James Harvey remembers how "if movies got franker, they also got dumber, it seemed, in other ways connected to that. The sins and terrors of the gothic small-town melodrama – as in 1941's Kings Row, for instance – turned with the new candor into the soap operas of 'repression' and 'maladjustment,' the homiletic culture of mental hygiene, as in 1957's Peyton Place. And it seemed like a decline – as if the movies were becoming more 'honest' and 'grown-up' only by telling us new and less obvious lies."

But if the film's box office means anything, it seems that audiences were eager for films that talked about sex – teen and adult – with any degree of candor or skill. While both Sylvia and Molly decide to give in to their emotions in spite of the consequences, only Sylvia gets called a harlot, a slut and an adulteress. And before she even consummates her love for Johnny, Molly has to endure a humiliating doctor's examination ordered by her mother after the teenagers are accidentally stranded on an island overnight.

By 1959 the Production Code was in tatters, allowed to fray and fall apart by the tacit, unacknowledged mutual consent of both the studios and the erstwhile "censors", and so A Summer Place is full of a lot of frank – and overwrought, and embarrassing, and cringe-inducing – discussion about sex and sin and desire. The teenagers are punished for their unconsummated love, but the adults they turn on most harshly are Ken and Sylvia, presumably for their hypocrisy in abandoning their marriages. At this point it has to be remembered that the late '50s and early '60s saw an unexpected (and mostly unremembered) spike in divorce, with the Greatest Generation reconsidering their youthful decisions in middle age – a trend that was definitely noticed by their Baby Boomer children.

Ultimately Aunt Emily was on to something, and despite paying alimony and child support and Molly's tuition at an exclusive private girls school, Ken can still afford to buy a Frank Lloyd Wright beach house after he marries Sylvia; they invite their children to stay in the hopes of mending their relationship, but the one tangible result is Johnny getting Molly pregnant. (It seems that Ken and Sylvia could get together every night in the boathouse that summer without incident, while the teenagers only need a single night to produce the result everybody had feared; it says something about innocence versus experience, I suppose, but that's one sexual topic A Summer Place neglects to discuss.)

At the end of the film, Molly and Johnny return to Pine Island for their honeymoon, and an escape back to the abiding lure of the summer place that gave Wilson's book and Daves' picture its title. I didn't understand the importance of that place when I was young; in Canada the closest equivalent to the evocative phrase "a summer place" is the far more banal "the cottage," and in any case we were far too poor to afford more than a week's rental, one summer, at what was inevitably a buggy, mildewy cabin with an outhouse around a lake crowded with boats we couldn't afford to rent.

That splendid, edenic "summer place" of the book and movie came from American WASP culture – a possibly exclusive, perhaps even palatial summer home, sometimes inherited but often rented annually, next to water that could be its only link to the mainland and the stress and care of the city, jobs and school. With social mobility and the postwar economic miracle, these summer places were within the grasp of more people than ever before, in the shape of lakeside rustic cabins, beach houses or sprawling hotel complexes in the Catskills, the Gatineau Valley, the Hamptons, the Muskokas or the Adirondacks, with amenities ranging from a dock and some deck chairs to boathouses to private beaches and fully-staffed dining rooms.

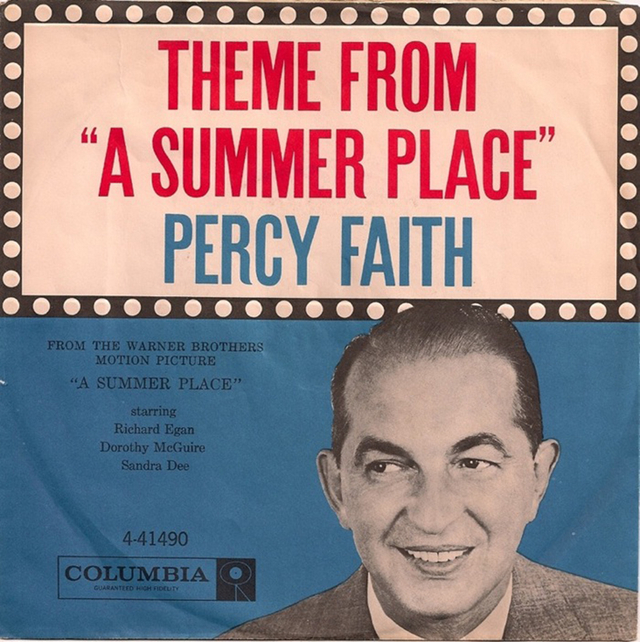

It's a longing for that place – a real memory for some, a fantasy for many others – that I imagined was the appeal of Percy Faith's "The Theme from A Summer Place", released on Columbia Records in September of 1959. Faith's version of Max Steiner's "Molly and Johnny Theme" did not appear in the movie, but was a re-orchestration, recorded in Columbia's 30th Street Studios on September 11, 1959 and credited to Percy Faith and his Orchestra.

The single struggled to gain a place in the charts until January of 1960, but it ascended to number one in six weeks and stayed there for nine consecutive weeks, holding off Jim Reeves' "He'll Have to Go", Bobby Rydell's "Wild One", Paul Anka's "Puppy Love" and Elvis Presley's "Stuck on You" from reaching the top of the charts. It remains the longest-running instrumental number one in history, and held the record for longevity at number one until it was unseated by Debby Boone's "You Light Up My Life" in 1977.

In her review of the film, Kristen Lopez calls Faith's recording a "schmaltzy earworm from Hell." The rhythm is waltz-like (though not, technically, a true waltz) and the strings rich and syrupy, answered by throaty horns in what sounds like a swooning call and response between girls and boys, finally uniting in unison near the end – not quite a musical approximation of coitus, but more like fully clothed foreplay.

Faith's version still sounds best coming from a car or a transistor radio, at a distance, bathed in reverberation and fighting with ambient sounds. That's how I imagine most people heard it for years to come, as it remained a staple of AM Top 40 radio and then "Music of Your Life" stations with their easy listening playlists. It's often noted that its chart topping run happened in the middle of winter; if you heard it in anywhere north of the 39th latitude in North America, it would make you painfully nostalgic for either the summer that had just passed or the precious one yet to come.

The single would win the 1961 Grammy for Record of the Year, the first movie theme and the first instrumental to win the award. A version with lyrics by Mack Discant would be recorded by Norrie Paramor, Andy Williams, The Lettermen, Cliff Richard, Skeeter Davis and Los Straitjackets, among others. I'm particularly fond of Julie London's version, which does a lot to divorce the song from the sloppy melodrama of Daves' movie, and distill the longing, lush, nostalgic appeal of the song – and the whole idea it evokes – down to its bittersweet essence.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.