The great irony of Cuba is that the revolution that created the modern state, a communist autocracy led for decades by Fidel Castro and his family, has actually pickled the whole country in time; the permanent revolution constantly celebrated by the regime has slowed down progress to a snail's pace, even seeming to go into reverse. Tourists are constantly raving about the old cars and the architecture – everything from Spanish colonial to midcentury modern – as it fades away and collapses in the sun and humidity, and come back complaining that it'll be ruined when Cuba finally rejoins the modern world.

You need to go back three generations to find a time when the Cuban revolution actually seemed like a vital, contemporary, even (depending on where you live politically) admirable national adventure. Alternately, you can watch a movie like Tomás Gutiérrez Alea's Memories of Underdevelopment (1968), a document of the first years of life after the revolution, released less than a decade after Castro took power.

The movie follows Sergio (Sergio Corrieri), a middle class intellectual who opts to stay behind in Havana after his family – his mother and father and his wife, who is divorcing him – leaves the country for Miami. He has a decade or so left to collect the rents on some properties he owns before the state takes that income from him, and he has his penthouse apartment in the FOCSA building in Vedado, one of the last skyscrapers built before the overthrow of Batista, and still the tallest building on the island.

He's left with his wife's clothes and his books and their art collection, and a telescope on a tripod on the balcony which he uses to survey the city – kids playing in schoolyards and sunbathers on loungers around a pool and the nearby Hotel Nacional, the most glamorous hotel in the city. Most of all, he's left with his memories, which he retreats into increasingly as the country around him goes through a tumultuous period from the Bay of Pigs invasion to the Cuban Missile Crisis.

I saw the film for the first time in 1991, on one of the state-controlled stations available on the TV in my room at the Habana Riviera, a hotel opened in 1957 by the gangster Meyer Lansky. I was in Cuba for the first time, a photographer documenting the recording of an album by some jazz musician friends – the first time a Canadian (or anyone) had made a record in the country since the revolution.

I was dealing with culture shock on top of the heat and humidity, trying to make sense of what I was seeing on the streets there, distinct from what I'd read in western media and in the country's own propaganda. The only English newspapers available were odd copies of the International Herald Tribune that somehow made their way to the newsstand in the hotel lobbies, and the English language edition of Granma, the official party newspaper, full of dreary accounts of agricultural plans, selections from Fidel's interminable hours-long speeches, and occasional, accidentally hilarious retellings of news events in the U.S.

Alea's film was at odds with the stolid, embattled image the regime presented of itself then, at the beginning of the "Special Period," when Soviet aid to the country was withdrawn after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rapid dissolution of the Warsaw Pact. Memories of Underdevelopment was stylish and avant garde, obviously influenced by the nouvelle vague and especially Jean-Luc Godard, and happy to entertain a moral ambiguity that was as rare in a communist country as fresh produce.

I was surprised to see it screened in a prime time slot on state television, and to learn that it had been produced by the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), the state-controlled film production agency, set up just after Fidel's revolution and co-founded by Alea. But as I was to learn on that trip and in subsequent years, Cuba's version of communism isn't like the one you find anywhere else. It's an anomaly that persists thanks to unique circumstances, much like (but totally different than) North Korea.

(As an aside, the title of the film has always made me chuckle. Up here in Canada one of our big grocery chains sells a famous series of premium bottled sauces meant to evoke a cuisine or a place: Memories of Argentina, Memories of Montego Bay, Memories of Szechwan. I wonder what a Memories of Underdevelopment sauce would taste like; based on my time in Cuba, I'd say rum, fermenting trash, diesel fumes, mildew and surprisingly great coffee.)

Alea's film was based on a novella by Edmundo Desnoes, and the writer was so enthusiastic about collaborating on a film adaptation that when an English translation was published, it included material created for the film. In an interview included on the Criterion Collection edition of the movie, Desnoes describes Corrieri's Sergio as a "poor man's Mastroianni" and he's dead on: he might be middle-aged (the actor was only 28 during filming, but he worked hard with the director on his character, dyeing his hair for the role) but like many of Mastroianni's best roles, Sergio's still a bit of a boy, poking through his wife's things after she leaves, pulling one of her stockings over his head, drawing on a mirror with her lipstick.

His motivation for remaining behind is mysterious; it might be perversity or nihilism, laziness or even fear – as unhappy as he is with what he's seeing in Havana, Sergio might be even less comfortable in America, becoming a man alienated not just with his hometown but by the world. Better the devil he knows, one supposes, which doesn't mean he won't indulge in the luxury of complaining, the cheapest luxury of all.

At heart, Sergio is more than a little misanthropic; he has no kind memories of either his wife or his best friend Pablo, another Havana bourgeois who decides to flee to the States. He drives around with him in his big American car, which Pablo knows he'll have to surrender to the state in working order as a condition of leaving the country, and listens to his predictions about the imminent failure of the revolutionary state. (Much of which have turned out to be true.)

He calls his friend a jerk in a voiceover at the airport while he watches him prepare to board his plane, musing that people like Pablo had to be "vomited out." Pablo is essentially a caricature of the Miami Cuban, the diaspora that conspires against the regime and helps maintain the Cuban economy through cash remittances to family back home. When he leaves, Sergio is left without friends or family, a fate he seems to relish.

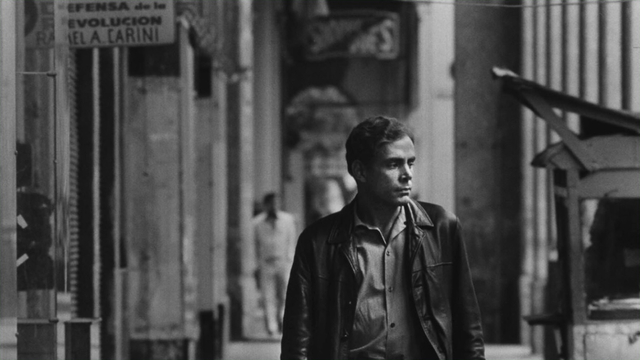

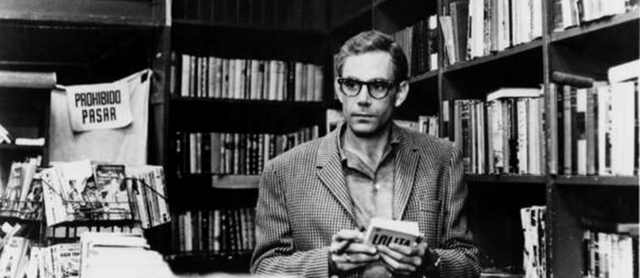

On his own, Sergio is free to try and "live like a European," wandering the streets as if Havana in 1961 is Paris or Barcelona or Madrid. What struck me about the same place in 1991 was how much worse everything was after three decades; in one scene Sergio is strolling through Vedado and walks into a bookstore, past a rack of used American paperbacks to shelves full of new revolutionary texts, either the product of state publishers or Progress editions imported from Moscow.

By 1991 most of the retail life in Havana was gone. After a week in the Riviera I moved closer to the recording studios – into the Inglaterra, the oldest hotel in the country, on the tree-lined Paseo de Marti boulevard that runs through the centre of the old city, just a block away from the dome of the capitol building. There were still a few neon signs hanging over the streets (none still lit; my favorite simply read: "SUBLIME") but the businesses that used to trade beneath them were long gone.

Storefronts were empty or converted into homes, but a few remained, mysteriously. On the walk to the studio every morning I'd pass a camera store with a display of Czech film in the window; worried about running out of film, I went in one day to buy a few rolls. I was told that they had no film, and hadn't for some time – the boxes in the window were just for show. I'd worried that buying film would deprive some Cuban photographer, but felt marginally better when it was obvious that neither of us could purchase what wasn't there.

The shelves in the grocery stores were always empty, which wasn't the case in the US dollar-only stores that were then off limits to regular Cubans; we'd end up getting dollars from musicians and other Cubans who'd obtained them from either touring or tourists and take their shopping lists into the dollar stores. I ended up shopping for many of the members of the band in the bar at the Inglaterra; sneakers were a particularly hot item.

In a country that celebrates its high rate of literacy, I never saw an open bookstore, and by 1991 even revolutionary texts were as scarce as those old paperbacks. When I returned to Havana four years later the Special Period had made things worse. A friend told me about an apartment building much like his own collapsing in Central Havana, a not-uncommon tragedy. Another friend – a government official – told me to avoid ordering a Cubano, the city's signature ham, pickle and cheese sandwich, since he couldn't guarantee that whatever was in it was ham. There were a lot fewer stray cats and dogs to be seen on the streets than four years earlier.

Now a single man, Sergio is free to look for the one thing he knows isn't scarce or rationed in Havana. He starts fantasizing about Noemi (Eslinda Núñez), the young woman who cleans his apartment three times a week; she's from the countryside, a Baptist (an exotic in a country still nominally Catholic or devoted to Afro-Caribbean Santero), and he has camp, gauzy fantasies about officiating at her immersion in a river, her baptism gown clinging wetly to her body – scenes that wouldn't be out of place in a Kubrick or Ken Russell film.

But his roving eye settles on Elena (Daisy Granados), a teenager who wants to become an actress. He offers to help her get a break (introducing her to a director friend of his at ICAIC – none other than Alea himself) and lures her back to his apartment with an offer to try on and take home some of his wife's dresses. It's a fitfully awkward seduction that ends in tears, but when Elena returns cheerfully the next morning it looks like she's going to become the muse of Alea's film, like Jean Seberg in Breathless or Anna Karina in Vivre sa vie.

But the age difference predictably makes Sergio bored with Elena; he tries to introduce her to culture at bookstores and art galleries, but she can't hide her disinterest. They visit Ernest Hemingway's house on the outskirts of Havana, preserved like his home in Key West as a museum, full of books, guns and trophy heads. Not unreasonably, Elena finds it a bit tedious and macabre, and when they get separated, Sergio hides from her, peering out from a window until she hitches a ride back to the city with some tourists.

Sergio looks on Elena as an embodiment of the underdevelopment that afflicts his country – the near-fatal flaw that makes him regard it (and her) with growing contempt. In one key voiceover monologue (the film, like Desnoes' book, is relentlessly told from Sergio's first person viewpoint) he mingles his disappointment with both Cuba and Cuban women over a montage of Granados' Elena:

"She doesn't connect things. That's a sign of underdevelopment, an inability to connect things, to accumulate experience and develop. It's rare to find a woman here shaped by feelings and culture. The environment is too bland. Cubans waste all their talents adapting to every moment. People aren't consistent. And they always need someone to think for them."

It's a damning judgment, and you can see why Alea and Desnoes were always vigilant about not being dissidents despite it – that these were the thoughts of Sergio, an alienated bourgeois; a man unwilling and unable to take part in the great social movement surrounding him. Which doesn't mean that it isn't true, but it's the sort of dismal criticism anyone disappointed with their country's culture could make, especially nowadays; I can't help but read it and think of Canada.

Sergio calls Elena a woman, but she's really a girl – either 16 or 17 depending on who you believe after her brother and parents angrily track him down and accuse him of taking her virginity, charging Sergio with rape and bringing him to trial. When her parents confront him at a restaurant, he tries to dismiss her mother's insistence that virtue is a girl's most valuable possession.

"Women are liberated now," he responds, reaching for the standard mantra of men who would be the real winners of the sexual revolution.

Her brother sees right through him: "Don't talk as if you were a revolutionary."

At the trial, Sergio's internal monologue imagines that he's the victim, a moral scapegoat, separated from the herd, being persecuted by Elena and her family, representatives of "the people." Ultimately, though, he's acquitted – Cuban sexual morality was, and is, still very much of a piece with Latin American machismo – and Elena is jettisoned from his life as neatly as if she'd left for Miami with Pablo and his wife; his greatest regret is that her parents might have had Elena committed.

In a flashback scene we learn how Sergio had become so cavalier about sex: like many boys of his class, he'd been initiated into sex at brothels, with the encouragement of his "progressive" father. Brothels were a fixture in Batista's Havana, but the revolution closed them down along with the casinos, pronouncing the equality of men and women in the new society. But prostitution was back big time by the Special Period, and every night when we got out of our cabs at the Riviera, we had to run a gauntlet of jinateras – girls and women selling sex, which thrived alongside the black market in bootleg cigars and rum.

It had begun earlier, with mostly male sex tourists from Germany, Mexico, Canada and elsewhere, who you'd see working on their sunburns by the pool at the hotels, attended by a young Cuban woman, often with a friend of hers sitting on a deck chair nearby – the "spare", ready to step in if her friend was suddenly unavailable. By the time I returned to the Inglaterra in 1995, any lone male enjoying the band in the hotel bar would expect to be interrupted by a woman who would sit herself down at their table uninvited, let in by a doorman who acted as her ad hoc pimp; if you let her order a drink, it was assumed you were in for further charges.

This was a huge embarrassment not just to the regime but to many Cubans. Daisy Granados would become one of Cuban cinema's biggest stars, and in an interview included with the Criterion release, she talks about Elena as a sort of "sexual mercenary" who anticipated a choice that young Cuban women would end up being forced to make in the future, with the return of tourism and the lack of anything else to sell.

Her words and body language make it clear that Granados isn't comfortable addressing the subject; she speaks euphemistically, and often leaves sentences pointedly unfinished, but anyone who's visited the country in the last three decades knows exactly what she's so clearly upset about. Considering what an impression of liberation and even abandon Cuban street culture, music and dancing can suggest, outsiders are often surprised at how traditional, even prudish, Cubans really are; it's what makes the rise of the jinatera and the jinatero such a troubling product of Cuba's revolutionary progress right back to the '50s.

In 1970 K.S. Karol, a Polish-born journalist, published Guerillas in Power, the definitive history of the first decade of the Cuban Revolution for many years. He tells an amusing story of a dinner given in honour of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin at Vedado's Habana Libre hotel in the summer of 1961. Karol had expected the usual long speeches, but he was surprised when a curtain rose and dancers from the Tropicana Cabaret performed specially written numbers:

"At once an enchanting troupe of dancers rushed onto the stage: the blondes, who wore the hammer and sickle, appeared to be exceptionally light on their feet, and seemed almost to touch the stars; the brunettes, wearing the stars and stripes, tried in vain to copy them. The blondes then put out their tongues at their unhappy rivals. There was a roar of applause for this demonstration of Russian superiority in space over the United States. The whole thing ended with a wild dance on the theme Cuba sí, Yankee no! to the accompaniment of much head-wagging and hip-wriggling. The Cubans could barely keep in their seats as they encouraged the dancers with shouts and hand clapping before finally joining in their chorus of Y viva la Revolución! The Russians from Gagarin downward seemed rather torn between their admiration for this fine display of feminine beauty and their doubts as to the socialist character of the performance. They clapped politely, without getting to their feet, determined not to let themselves be carried away. As for the Chinese, present in equal numbers, they remained quite impassive at the end of the table; their eyes were closed, and from what one could tell they were sleeping peacefully."

I can't imagine that Cubans weren't aware what an exotic curiosity their country looked like – to both the socialist world and the capitalist west. In the '70s it was fashionable for young radicals to fly into the country and labour in the fields alongside the locals – a situation that was hugely amusing to Cuban farm workers. (I wonder if they returned when they were older to enjoy the resorts in Varadero when they started to open.)

In one scene, Sergio is surveying the city from the telescope on his balcony. He stops at the 1925 monument to the victims of the explosion of the USS Maine by the Malecon, the city's seaside road, and the empty spot at the top of two classical columns where the American eagle had been torn down by the revolutionaries. Picasso had promised to travel to the city and replace it with his "Dove of Peace," but never made the trip. It's still empty today.

"It's easy to be a communist millionaire in Paris," Sergio says to himself.

Even as the events in his life and his country become more threatening, Sergio refuses to abandon his studious indifference; one of the iconic images from the film – apparently a scene improvised by Alea and his crew when the city was shut down by a political rally – is Sergio with his back to the camera as it follows him, walking against the crowd singing revolutionary slogans and carrying Cuban flags.

Eager not to glorify their protagonist or to position themselves in opposition to the regime, Alea and Desnoes repeatedly stated that Sergio wasn't them, even if the circumstantial resemblance was undeniable, and that his denial of his place in the revolution was irresponsible. Nonetheless, their film ended up being popular with Miami Cubans who said that it described their reasons for leaving perfectly, and I can't help but admire Sergio – not for his stunted morality, but for his insistence on not being part of a crowd, or a mob, or a movement.

Late in the film, Sergio remembers his first love – a German girl whose family fled the Nazis and ended up in Havana. She left with them for New York and he had promised to follow her, but just as the revolution couldn't make him leave, he never managed that escape either. The story is based on one from Desnoes' own life, and when his book and the film were famous, his lost love contacted him. He left Cuba and rejoined her in New York City – just one among the tens of thousands of Cubans who've left, in planes or in leaky boats and rafts.

In the meantime Cuba has gone in for tourism in a big way. The Habana Riviera is now run by Iberostar, a Spanish company, and the Melia Cohiba, which was being built next door to the Riviera by another Spanish hotelier in 1991, is currently closed for refurbishment. Marriott announced that it would manage the Inglaterra in 2016 and make it part of their portfolio of luxury hotels, but deadlines for the relaunch passed for the next four years until the Treasury Department under Trump ordered Marriott to cease their business in Cuba. The Melia group runs the Habana Libre; the Hotel Nacional is owned by Gran Caribe Group, a hotel management agency owned by the Cuban government. In Cuba today, anyone with access to tourists, from cab drivers to doormen to chambermaids to bartenders to members of hotel bands, makes more money than a doctor or engineer.

As the film comes to an end the scope of Sergio's possibilities are shrinking. He'll lose his income in a decade, and when he gets a visit from members of the local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution (the CDR; the closest Cuba ever got to East Germany's Stasi), it's obvious by the way one woman resentfully eyes his apartment that he won't be living there much longer. (The FOCSA building became housing for Soviet and Eastern Bloc advisors; lately it's been used to house guest workers from Venezuela.)

The system will guarantee him an income and some sort of job, and he'll end up one of those old men living in a crowded, decaying apartment building in Centro Habana or in a room by the Malecon – if he doesn't make his exit to Miami. But the film leaves him alone in his penthouse, pacing from room to room as the Cuban Missile Crisis plays out over the sea beyond the Malecon.

At the beginning of the film Sergio surveys Havana with his telescope and remarks that "nothing has changed." At the end of the film there are no kids in the playgrounds and the loungers by the pool are empty as soldiers haul an anti-aircraft gun to the roof of a building; on the Malecon, a convoy of army trucks hauling guns make their way toward the Havana Riviera. Sergio crawls into his bed, and the country prepares to pull a lid over itself, sealing everything and everyone inside. Inside and outside Cuba, everyone wonders what will happen when they take the lid off again – and why it's taken so long.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.