I hadn't been following Anthony Albanese's (alas, successful) campaign to become Australian prime minister until I noticed him whingeing about a low-down dirty attack ad from Scott Morrison with the slogan:

Life won't be easy

Under Albanese...

As Albo sees it, rhyming his name is racist:

Anthony Albanese takes aim at Liberal Party for thinking 'it's still okay' to make 'fun' of his Italian name in advertisement.

Apparently, rhyming it subtly draws attention to how alien and un-Australian it is.

Well, he's had the last laugh on that. On the other hand, ever since he raised the subject, I've been wandering around singing "easy" numbers with "Albanese" wedged into the lyric, so I thought I might as well pick one such for our Sunday song selection.

In 1934 Cole Porter wrote one of the loveliest ballads in the American Songbook:

You'd be so Easy To Love

So easy to idolize, all others above...

It's a top-rank Porter standard, so Mildred Bailey is far from the starriest name attached to it. It's been recorded by Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday, Artie Shaw, Johnny Mathis, Carmen McRae, Charlie Parker, Tony Bennett, Ella Fitzgerald, Chet Baker, Bill Evans, Julie London, Stephane Grappelli, Sammy Davis Jr, Doris Day, and on and on and on, forever. Yet the guy it was written for didn't care for it.

William Gaxton was the leading man in Porter's new Broadway show Anything Goes, and in October 1934 he and the rest of the cast were getting ready to open in Boston at the end of the month. In rehearsals, the leading man decided the song wasn't right for him, notwithstanding that it's a number

...so worth the yearning for

So swell to keep ev'ry homefire burning for...

"Easy To Love", from its very title, is the epitome of Porter's brand of offhand sophistication, of romance as a glide across a glittering dance floor. If you ever hear an orchestra playing it in strict tempo, you appreciate how effortlessly the tune flows, and the lyric does its best to match the blitheness. There's a line in it I was faintly puzzled by as a young whippersnapper: "We'd be so grand at the game." As I grew older, I came to appreciate it more and more - the idea of love as a "game", and a couple taking pleasure in the notion of being good at it.

So I was startled to read, in his book The American Popular Ballad Of The Golden Era, 1924-1950: A Study In Musical Design, that Allen Forte believes "the game" refers to the annual Harvard/Yale football game, which was a big social occasion in Porter's day and still was last time I checked (pre-Covid). Mr Forte's contention is that the composer, a Yale man, is positing a couple so glamorous that they make a big splash at the football game. This seems most unlikely to me. The great quality of Porter's sophistication is that - unlike, say, Noël Coward's - it's not exclusive: it conjures a world of dancing till dawn and assumes that you too, Joe Schmoe out in Nowheresville, are invited to the party. In Broadway Babies Say Goodnight (personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the Steyn store), I quote a fellow composer: "It wasn't just a chi-chi theatre crowd who liked him," said Jule Styne. "His songs could make a shop girl feel that she'd been to El Morocco or the Stork."

Otherwise, he wouldn't have been America's second highest-earning songwriter (after Irving Berlin), and it wouldn't have fallen to a great American everyman, Jimmy Stewart of Bedford Falls, to introduce us to a love song that falls into a category we might label (after another classic Porter line) "a trip to the moon on gossamer wings". It's like those self-improvement advertisements of the same period: They all laughed when I said it would be easy to find someone who's easy to love. But a Porter song puts it within anyone's reach. So no, I don't think being "grand at the game" is a reference to Harvard and Yale playing football.

Even without "Easy To Love", Anything Goes proved to be a smash in the fall of 1934, and eventually the fourth-longest running Broadway show of the Thirties. Its glorious score includes not only the title song but also "You're The Top" and "I Get A Kick Out Of You". Ethel Merman had a ball with those. But William Gaxton, a huge Broadway star in his day, found "Easy To Love" a tougher haul, and complained about the ballad's range. It's an octave and a fifth: Porter put the "be" of "You'd be..." way down on the A below middle C and then worked his way toward that exhilarating leap at the end of "all others above". Appropriately enough for the lyric, the tune jumps on the "-bove" of "above" up to D natural, and then goes above that for the "so" of "so worth the yearning for". A lot of pop singers look at the low A in that second bar and take it an octave higher, which you can certainly do, but it undeniably weakens the song. At any rate, William Gaxton didn't fancy his chances with it on stage every night, and took his concerns to Porter in hopes that he might amend it. But the composer had a basic rule: "Rewriting ruins songs." So he rattled off a replacement for Gaxton - "All Through The Night", which is lovely, if not quite as lovely as the ballad it replaced - and he stuck "Easy To Love" in the trunk.

Flash forward a year. It's December 1935 and Cole and Linda Porter have just arrived in Hollywood. He's signed a contract to write the words and music for his first film score, but he gets off the train to find there's no script, no plot, no outline, no premise, no nothing. And certainly no stars. It was supposed to star Clark Gable and Jean Harlow, but then someone at MGM noticed what everyone else in town already knew: neither Gable nor Harlow could sing. So, as one does, they dump Clark Gable and get Sonja Henie and all of a sudden the film is a skating musical. And at some point the skating idea is nixed, so Sonja Henie disappears, and in its latest incarnation the film's supposed to introduce American audiences to the great British star Jessie Matthews, playing opposite Robert Montgomery. But Miss Matthews' British studio refuses to loan her to MGM, so the film's retooled yet again, and Bob Montgomery decides he doesn't like what's happened to his part and so he walks.

Porter took all this in his stride. He found the Hollywood life very agreeable by comparison with New York: He rented a big estate and he lounged by the pool telephoning and tanning and waiting for the studio honchos to settle on a star and a story. At one point, the producer, director and writers asked Porter if he could sing them a song or two and it might give them some ideas on what the film should be about and who they should get to be in it.

And so it was that one morning Cole Porter sat down at the piano in front of the producer Jack Cummings and various other MGM swells and warbled:

You'd be so Easy To Love

So easy to idolize, all others above

So sweet to waken with

So nice to sit down to eggs and bacon with...

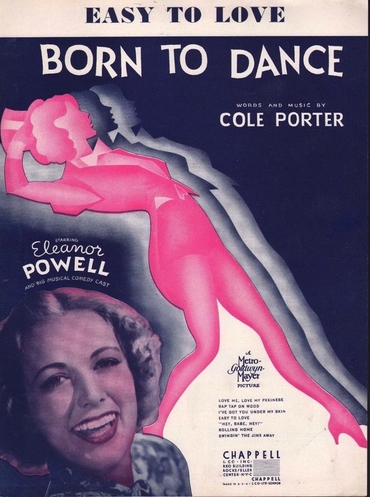

"The response was instantaneous," he wrote in his diary. "They all grabbed the lyric and began singing it, and even called in the stenographers to hear it." So he had a surefire song. Now all he needed was someone to sing it. To headline the picture, MGM settled on the pneumatic tapper Eleanor Powell and called it Born To Dance, which seems reasonable: With the best will in the world, you couldn't call an Eleanor Powell vehicle Born To Act. The plot was now something involving a submarine putting into New York harbor and the boys heading over to the Lonely Hearts Club where Eleanor Powell is rat-a-tat-tapping away and the lead lad, Ted, is smitten by her but a big Broadway star gets sent to the submarine to promote her show and as a publicity stunt the press agent concocts a romance between her and Ted and then Eleanor Powell gets hired as the big star's understudy on the Broadway show only to be fired when the star discovers Ted's really in love with her understudy. Etc. It's one of those musical comedy plots you could run backwards and no-one would care. But who to get for Ted, Eleanor Powell's leading man?

Porter suggested a lanky boyish actor on his way up: Jimmy Stewart. Jack Cummings liked Stewart but didn't think he could sing. So the next day Stewart came round to give his pipes a work out for Porter. "He sings far from well, although he has nice notes in his voice," wrote Cole in his diary, "but he could play the part perfectly." A stage-and-screen composer makes such compromises all the time. The advantage Stewart had over William Gaxton was that he didn't know enough to know the song had too wide a range for him. Unaware that he couldn't do it, he just got on and did it.

The trick is the verse. The chorus has an easy confidence and, while that's fine if you're Sinatra launching into a ring-a-ding-ding arrangement with Johnny Mandel, it might not be entirely convincing for an actor who became the master of small-town semi-stammered diffidence. But Porter's verse sets up the situation perfectly. Stewart and the unlikely object of his affection are strolling through Central Park, and suddenly there he is - Jimmy Stewart's singing, and the high voice on the Cs and Ds of "care for me" are utterly charming:

I know too well that I'm

Just wasting precious time

In thinking such a thing could be

That you could ever care for me

I'm sure you hate to hear

That I adore you, dear

But grant me just the same

I'm not entirely to blame

ForYou'd be so Easy To Love...

This being Hollywood not Broadway, Porter's couplet about being "so sweet to waken with/so nice to sit down to eggs and bacon with" was taken by the producers not as an affectionate paean to domestic routine but as the aftermath of an incendiary night at a hot-sheet motel. So he was prevailed upon to make a substitution:

So worth the yearning for

So swell to keep ev'ry homefire burning for...

If that rhyme sounds familiar, Porter had used it a couple of years earlier:

There's an oh, such a hungry yearning burning inside of me...

But "Night And Day" is passionate, ardent, obsessed. "Easy To Love" is supposed to be easy, and I'm not sure "yearning" is quite le mot juste. On the other hand, the reference to Ivor Novello's Great War chin-up song - "Keep The Home Fires Burning" - takes a somewhat stiff strain of British stoicism and makes it human and intimate.

However, Jimmy Stewart did record the original soi disant morning-after couplet before the studio banned it - and some clever fellow did edit it into MGM's footage of the scene:

What appeals about the forbidden couplet is not any sexual implications but the domesticity of it. As he often did, Porter wrote three full choruses for "Easy To Love" and the lesser-known lines have their moments. I like this:

I know I once left you cold

But call me your lamb and take me back to the fold...

And this:

Oh, how we'd bloom, how we'd thrive

In a cottage for two, or even three, four or five...

But by the time we get to the third chorus the lyricist seems to have run out of things to say and largely forgotten what the song's about:

You'd be so Easy To Love

So easy to worship as an angel above

Just made to pray before

Just right to stay home and walk the baby for...

Does one really "walk the baby"? Isn't that the cocker spaniel? Heigh-ho.

What with Eleanor Powell dancing the song, and Reginald Gardiner as a passing Central Park cop doing an impression of histrionic symphonic maestros while conducting an invisible orchestra that mysteriously segues from Ponchielli's "Dance Of The Hours" into "Easy For Love", Porter found he'd written more lyrics than the film needed and the movie wound up with a kind of condensation that most pop recordings have wisely stuck to.

When the picture was released in November 1936, it was "I've Got You Under My Skin" that attracted the critics' attention and eventually an Oscar nomination (it lost to "The Way You Look Tonight"). But not everyone thought Porter was well-advised to entrust his most sublime ballads to James Stewart. One critic said that the scene reminded him of "the hired man calling in the cows for supper. They come in with a smile, but they look rather surprised," he wrote. "Stewart is very much like the rest of us average guys. Only our singing, like his, should be reserved for the shower." It didn't seem to hurt "Easy To Love". Frances Langford and Shep Fields both did well with the song on the hit parade. As the actor himself put it, "The song was so good that not even I could spoil it."

As you'd expect from Jimmy Stewart, he's being too modest. A couple of choruses after his light fragile tenor vocal, Eleanor Powell is high-kicking around the statues and you realize Stewart's verse and chorus are the only affecting, human moments in what's otherwise a blow-out of generic production-line bombast, culminating in a star-spangled Miss Powell tapping away surrounded by orgasmic cannons blasting off. Abe Burrows, the co-author of Guys and Dolls, liked to say that in a musical a character who doesn't get a song isn't really in the show. In Born to Dance, everybody gets a song - but the non-singer Stewart is the only one who really sings.

Still, as Frank's pal Alec Wilder put it, "If ever there was a song that shouldn't have a note changed, it's 'Easy to Love.' Nor, as far as I'm concerned, any of its harmony." And, when a song's that good, you want a singer that good, too. Sinatra came to it almost a quarter-century after Jimmy Stewart for his first album at his own record company, Reprise. Capitol's contracts with Nelson Riddle and Billy May prevented Frank from using either of his regular swingin' arrangers, so he was forced to look elsewhere and settled on Johnny Mandel, who had never arranged a vocal album before, although you'd never know it. He went on to become a legendary Oscar and Grammy winner, but Ring-A-Ding Ding! was the project that changed his life.

The album offers a supremely confident Sinatra with a sound just different enough from the Capitol days to give a freshness to the new Chairman's swagger. On "Easy To Love", Don Fagerquist's trumpet mute is a familiar sound from Harry "Sweets" Edison on Riddle's charts, but I'm not sure that May or Riddle would have put that lovely vibraphone in there. Just for the record, according to Mandel, because of time pressures, he wrote the intro and outro and instrumental break of "Easy To Love" and called in Dick Reynolds for the bits of orchestration Frank's singing over. If that's so, you can't see the join. The track is under two-and-a-half minutes, but travels a ways in that short time, building and building, until Sinatra is having the time of his life:

We'd be so grand at the game

So carefree together that it does seem a shame...

The orchestral whump that punctuates the two syllables of "carefree" indicate a band and singer totally in sync, and indeed grand at the game. The sessions were attended by Frank's 16-year-old son. "The recordings were made the week before Christmas," Frank Jr recalled, "and the smiles on his face during those three nights left no doubt in anyone's mind that for Sinatra Santa Claus had come early."

As for the man who introduced it, "Easy To Love" was pretty much it for Jimmy Stewart, boy vocalist. He sang "When Johnny Toots His Horn" in Pot O' Gold a couple of years later, in 1938, and then kept his vocal powder dry until Lassie, Come Home, right at the end of his film career in 1978, when a bit of good-natured grandfatherly talk-singing got hammered by the critics as unbecoming to a star of his stature. But Porter at least retained an affection for the boyish modesty of young Jimmy's original performance. When the composer died, the University of Southern California inaugurated the new Cole Porter library with an all-star panel: Garson Kanin moderated a discussion by Ethel Merman, Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Alan Jay Lerner, Frank Sinatra ...and Jimmy Stewart. Roger Edens, from the old MGM music department, was at the piano, and Frank did a pure ballad version of "I've Got You Under My Skin" plus "It's All Right With Me" and "Let's Do It" and a couple of others, and Merman, Astaire and Kelly all sang, too. And right at the end of the evening James Stewart topped them all by reprising his winning performance of "Easy To Love". He set it up beautifully, explaining how way back a third of a century earlier, when he'd been rehearsing it with Roger Edens, he'd noticed that some of the notes seemed, ah, rather high. And then he sang the song, and reached for the big note at the end of "does seem a shame", and he gave a rueful smile and the audience loved it. It's the old can-do spirit: Jimmy Stewart, the citizen-legislator in Mr Smith Goes To Washington, was a citizen-singer that night at USC. And Frank was more than happy to let Jimmy have his song back:

We'd be so grand at the game

So carefree together that it does seem a shame

That you can't see

Your future with me

For you'd be

Oh, so Easy To Love.

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

If you're a Steyn Clubber, feel free to weigh in in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.