In the dark arts of public relations, overexposure is the ticking time bomb – the fatal trap waiting for every artist or product or brand as punishment for success. For movie fans, there's always a list of films – long or short – that you can love or even own but which you will unconsciously avoid watching because, simply put, you've seen them too many damn times.

(This is distinct from the even shorter list of films you can watch over and over, even when you chance on them halfway through on TV in a hotel. Mine includes Patton and Goodfellas.)

Humphrey Bogart was my youthful gateway movie icon into classic Hollywood, specifically with the re-release of Casablanca into movie theatres at the end of the '70s. I've lost track of how many times I've seen Casablanca, but I'll admit that I'll go out of my way to avoid watching it again. (Unlike, say, The Maltese Falcon, which is on the same list as Patton and Goodfellas.) The result is that I'm grateful to see almost any other Bogart film made after he ascended from b-pictures and generic gangster movies. And why I've come to enjoy Beat the Devil more than Casablanca, which to most people might sound utterly perverse.

Beat the Devil was released in 1953, the sixth film Bogart made with John Huston as director, and it's often denigrated or overlooked among the acknowledged classics the two men made together, which included The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Key Largo and The African Queen. Some documentaries about Bogart pointedly ignore it altogether – including the one that came as a bonus feature with my DVD of Beat the Devil.

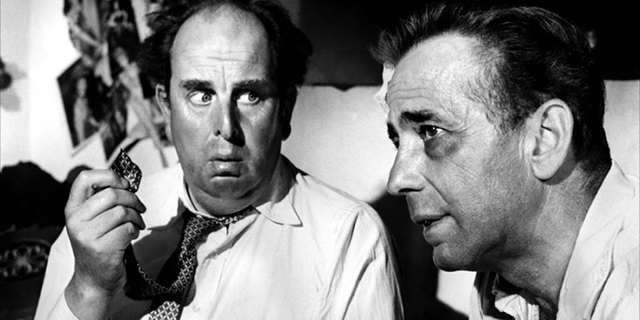

The film was a box office flop, probably because it undercut and even parodied the stoic, solidly heroic public image that was key to his onscreen persona since he became a star at the beginning of the '40s. (Much like another favorite Bogart picture of mine – In A Lonely Place, reviewed here late last year.) It was, in fact, conceived – albeit later in its production cycle – by Huston and Bogart as a satire of their first hit, The Maltese Falcon, with Peter Lorre called upon to play a dispirited reprise of his Joel Cairo, and Robert Morley cast as a far less sinister version of Sydney Greenstreet's Kasper Gutman.

The film begins with a raucous brass band playing in the square of one of those Italian seaside towns that have become bucket list tourist destinations, a credit sequence set to a tune as emphatic as it is out of tune. It would be a great description for the film that follows.

Bogart is Billy Dannreuther, an American down on his luck, though nothing like Fred C. Dobbs, as he sports dressing gowns and cravats and used to own one of the big mansions outside town overlooking the sea. He's fallen in with bad company – a quartet of criminals notionally led by Morley's Peterson, an unctuous, bullying Brit, accessorized with Lorre's O'Hara – a German with an inexplicably Irish name – along with an Italian (Marco Tulli's Ravello, named after the town where much of the film was shot) and Major Ross (Ivor Barnard), an altogether much less charming Brit than Peterson.

They have an inside line on mineral rights to a uranium deposit in British East Africa (now Kenya) – an angle that they've apparently guaranteed by having the homicidal Major murder an official in the Colonial Office in London before their arrival in Italy. They're waiting to depart on the Nyanga, a boat leaving for Africa – a boat whose sailing is constantly postponed either by a faulty engine or a drunken captain, with updates regularly provided by the ship's purser (Mario Perrone), the only man who seems to have a handle on either what's happening or what's possible in this picturesque but purgatorial patch of rocks and sand beneath the sun.

If you only watched the first five minutes of the picture, you'd assume that the wild card in this rickety criminal conspiracy would be Billy's wife, Maria. She's played by no less than Gina Lollobrigida, the Italian bombshell who dominated that archetype until the arrival of Sophia Loren later in the decade. Maria's loyalty to Billy looks provisional, dependent on the outcome of the criminal enterprise, though Bogart's Billy doesn't seem particularly bothered by his wife's constant telegraphing of her unfaithful intentions.

The real threat to the plans of "the Committee," as Peterson refers to the quartet of conspirators, is actually the Chelms, a British couple who suddenly show up to take their berth on the Nyanga. Harry Chelm (Edward Underdown) is a classically pooterish middle class Brit, outraged by the slipshod standards of the world outside the Empire and afflicted with maladies that require a hot water bottle.

His wife, Gwendolen (Jennifer Jones), however, is the real agent of chaos in the story. A serial fabulist who spins lies with effortless conviction, she'll constantly upset the plans of Billy and the Committee by muddying the truth about her husband and everyone else, preferring an outlandish fantasy to the mundane truth at every opportunity. She's captivated by Billy's fall from fortune and makes herself available for an affair immediately, which gives Maria permission to start her own flirtation with the stolid, mostly clueless Harry.

Bogart's own production company, Santana, took on the risk of producing Beat the Devil when Huston suggested he buy the rights to a novel by Francis Claud Cockburn, an impoverished British journalist blacklisted for his communist ties. (Cockburn wrote the book under the pseudonym James Helvick.) He was a friend and neighbour of Huston's in Ireland, and the film began as an act of charity that Bogart would come to regret.

Bogart considered Huston a kindred spirit, and enjoyed working with him. "The monster is stimulating," he said of the director in an interview in 1950, quoted in John Huston: Courage and Art, Jeffrey Meyers' 2011 biography of Huston. "Offbeat kind of mind. Off center. He's brilliant and unpredictable. Never dull. When I work with John, I think about acting. I don't worry about business."

The biggest problem with Beat the Devil was the script; Huston tossed out the one written by Cockburn, and hated a second draft written by Peter Viertel (Saboteur, Decision Before Dawn) and Tony Veiller (The Stranger, The Killers, Moulin Rouge). Desperate, and with a week to go before shooting began, Jones' husband David O. Selznick recommended that Huston hire none other than Truman Capote, then living in Rome, to work with him on the screenplay.

They made a truly odd couple – the lanky, gruff, macho Huston and the slight, effeminate Capote, all the stranger as the writer and director shared a hotel room during shooting, to the delight of Bogart, who invented racy rumours about them for his amusement. Like most people, however, Huston was charmed by the elfin writer, and even had Peter Lorre's hair dyed and styled to match Capote's straw-like blonde bangs.

Everyone involved in the production remembered shooting as a debauched party. Huston recalled that "it was a hell of a lark doing it," and Capote echoed the director, saying that the offbeat fun was evident onscreen. With Huston and Bogart setting the tone, it was a typically drunken production, and Capote remembered that the two men "nearly killed me with their dissipations...half-drunk all day and dead drunk at night." Nonetheless, the writer repeatedly beat Bogart in arm-wrestling matches at $50 a throw, though the actor made it back with Capote's losses in a running high stakes poker game.

It was also an accident-prone shoot, with Huston walking off his patio one dark, drunken night and falling several dozen feet to the ground. Bogart was in a car accident just before shooting began, his driver splitting the difference between two forks in the road from Rome to Naples, and driving through a wall and into a ditch. Bogart tore his tongue and smashed his front teeth; he had his tongue stitched up by a German doctor in Naples without anesthetic, and while filming continued while his dental work healed, an actor and comic named Peter Sellers, unknown outside the UK, would dub his voice on the soundtrack, then went on to do the same for several Italian actors who couldn't speak English. (The purser, played by a restaurant pianist Huston discovered in Rome, is doubtless voiced entirely by Sellers.)

The script continued to be a problem; Huston and Capote usually wrote scenes the night before they were shot, and were often working on them while the crew waited, Huston contriving ever more complicated camera and lighting setups to buy him and Capote time. It explains the episodic, even picaresque nature of the script: a car accident, a shipwreck, an abduction by Arabs. Capote was certain that he was the only one who knew what was actually happening from day to day, a situation that was complicated when the writer suddenly left Ravello and returned to Rome to tend to his pet crow, Lola.

While nearly every character except Bogart and Lorre's enigmatic German-Irish-Chilean O'Hara is built around some national stereotype – Italians in general are reduced to a background chorus of shouting gesticulators – the main cast is still loaded with indelible characters. (The implication, of course, is that Lorre's character is the beneficiary of some "rat line" that secreted Nazis to South America after the war – ultimately another stereotype.) When Harry Chelm is revealed to be the product of a humble boarding house in Earlscourt and not gentry from some ancient country estate, his wife explains that he can't help the impression he gives with his manner and accent.

The most toxic stereotype of all is embodied in Peterson's "muscle" - Major Ross, a dangerous psychopath who spouts virulent, racist rants alongside a Mosley-esque appreciation for Hitler and Mussolini. He establishes his character indelibly in a single brief monologue, retiring to seethe in the background. Doubtless thanks to Capote's dialogue, every major character is gifted with countless indelible lines, contributing to the film's abiding charm.

The only thing holding the whole thing together is that the film begins with its ending – the "Committee" being marched in handcuffs to jail. The only surprise is the final revelation of Harry's fate, delivered by telegram, which hints that he might not have been as dim and hapless as he appeared. In his book on Huston, Jeffrey Meyers underlines that the film is ultimately like so many other Huston films: "a grandiose quest that ends in tragicomic failure."

All of the characters in Beat the Devil are essentially amoral, which is necessary for its wry comedy to work, though it might explain why the film bombed. Even in 1953, audiences might not have been ready for a Bogart character that is both ready and willing to cheat on his wife on what seems like a whim, with a wife who is just as ready and willing to cuckold him.

As much fun as it was to make the film, Bogart ended up regretting it, mostly because he was on the hook for a half million dollars when it flopped. It didn't help that it was released with a marketing campaign that promised torrid thrills and adventure. Peter Lorre remembered it as "a deliciously sardonic comedy, meant for art houses, and they opened it with a blood-and-thunder campaign. People just didn't get it."

For his part, a bitter Bogart dismissed it outright: "Only phonies think it's funny."

Coming off the success of The African Queen and Moulin Rouge, Huston was stung by the failure of Beat the Devil; his friend William Wyler advised him that it was "the kind of movie that, when you've finished making it, you should make another one as quickly as possible." Unfortunately the next film Huston made would be Moby Dick, a difficult production that barely made its budget back.

Bogart fared better – his next two films were The Caine Mutiny and Sabrina, though he had barely four years to live, succumbing esophageal cancer in 1957. Perhaps that's why nobody ever renewed the copyright on Beat the Devil, which has lapsed into the public domain along with films like It's A Wonderful Life, Carnival of Souls, Charade, His Girl Friday and The Strange Love of Martha Ivers. For as long as I remember the market has been full of cheap DVDs of the film made from often indifferent prints, though there's a perfectly decent version available to stream on YouTube.

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed Beat the Devil when I first saw it – after reading years of abuse – and have enjoyed it more with each screening. As Jeffrey Meyers writes in his book on Huston: "Sixty years on, Moulin Rouge is a maudlin bore, while Beat the Devil is still witty and entertaining, with excellent character roles and vivid, sun-bleached crime scenes. The film is much more amusing the second and third time around when the viewer has a clearer idea of its satiric comedy." In the end, I guess that makes me one of those phonies Bogart talked about.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.