If you care about movie genres there's a fun game you can play. Considering how fluid genres like war films, westerns, gangster movies and horror can be, especially at the peak of their popularity, it's worthwhile to take a film – in this case Edward Dmytryk's 1954 western Broken Lance – and pick it apart while asking "How Western is it?"

The film opens much as you'd expect, with a wide Cinemascope panorama of the grassy badlands of Arizona, the horizon curving through the ultra wide angle lens on the camera, a lone wolf running through the frame. The next scene, however departs from the usual script: a group of men wait outside the state prison while Joe Devereaux (Robert Wagner) collects his belongings after finishing a three-year stint behind bars. It's something we've seen in countless films, though usually in gangster pictures.

The men, however, aren't Joe's family or fellow gang members, but state deputies, who inform him that whatever his plans are, the first thing he's doing is visiting the governor. There's a long ride through the wilderness where Joe gets to show off his skill with a revolver, killing a sidewinder that was about to strike one of the deputies. We finally arrive in the state capitol – the state is never specified – which has evolved well past the painted barn board facades of the frontier town.

The streets are tidy, with a solid looking bank and land office, and a domed capitol building in brick and stone with marble floors in the foyer; we're obviously beyond the wild west years of the frontier wherever we are, and Joe stops to gaze up at an oil portrait of an older man displayed in a place of honour under the dome – it's a tribute to his father, Matt Devereaux (played by Spencer Tracy), and it looms over Joe and everyone else.

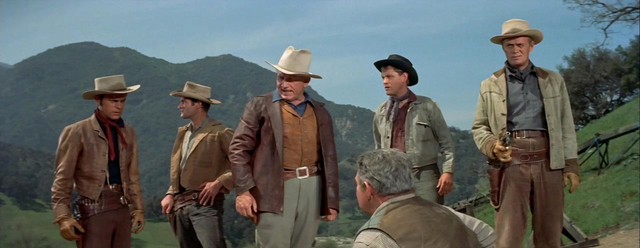

The governor (E.G. Marshall) tells the young man that he doesn't want any more trouble around Joe's family ranch, and that he's brokered a deal that he strongly suggests Joe should take, before ushering in Joe's brothers from the adjacent room. Ben (Richard Widmark) is the oldest brother, and clearly the brains of the operation, which is more than you can say for the youngest, Denny, played by western stalwart Earl Holliman; he's whatever comic relief the film requires, and it's strongly suggested that Denny might have fallen down a well or walked off a cliff if it weren't for his brothers.

The other brother, Mike, is harder to read. He's played by Hugh O'Brian, who would be cast in the title role of ABC's western series The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp a year later; his career would include everything from There's No Business like Show Business to The Shootist to Fantasy Island. His Mike is really there to make up the numbers of the Devereaux clan, and O'Brian does a lot with a role that asks little more than for Mike to look potentially dangerous.

The deal Joe's brothers offer him is simple – a big lump of money up front to leave town on the next train to Washington state and a new life on a ranch there, far away from his family. Because there's still nearly ninety minutes of movie left, he doesn't take the offer, and heads out to the family homestead, abandoned since his brothers moved operations for their property into town after their father's death.

In the ghostly ruins of the empty house, Joe stands in front of another oil portrait of his father and asks him for a sign to tell him what to do next. A pair of French doors blow open and fill the room with clouds of dust, and the flashback comprising most of the story begins.

Broken Lance was a remake, but not of a western: Dmytryk's film took the story from House of Strangers, a 1949 drama directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, which was based on I'll Never Go There Any More, a 1941 novel by Jerome Weidman that was, in its turn, more than vaguely inspired by King Lear. Edward G. Robinson played the patriarch in the original film, with Richard Conte as the youngest son in an Italian family struggling for control of a New York City bank. It would be remade again in 1961 as The Big Show, with Esther Williams and Cliff Robertson and the setting changed to a circus. It's a classic example of how big studios (20th Century Fox in this case) repeatedly recycle properties they own.

Edward Dmytryk was enjoying the start of a second act to his career when he made Broken Lance, the first act having been interrupted by the intervention of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Born in Canada, Dmytryk's father was a harsh disciplinarian in the mold of Tracy's patriarch rancher, without the wealth or land. The family moved California and Dmytryk got a job as a messenger at Famous Players-Lasky, before promotions to film projectionist and then editor on films such as Duck Soup and Ruggles of Red Gap.

He directed his first film, a b-western called The Hawk (or Trail of the Hawk) in 1935, but returned to the editing room for several more years before bouncing from b-picture to b-picture at Paramount, Monogram and Columbia. He had his first break with a pair of propaganda pictures at RKO, Hitler's Children and Behind the Rising Sun (both 1943), which led to Tender Comrade (1943) starring Ginger Rogers and Murder, My Sweet (1944), an adaptation of Raymond Chandler's Farewell, My Lovely that re-launched Dick Powell as a tough guy and provided the template for film noirs to come.

After over a decade's apprenticeship, Dmytryk's star rose quickly, with pictures like Back To Bataan (1945) with John Wayne, well-respected noirs like Cornered (1945) and Crossfire (1947) and Till the End of Time (1946), a film about returning servicemen that shares much with the more famous The Best Years of Our Lives, which came out a year later.

He was RKO's leading director when the subpoena from HUAC came; Dmytryk became one of the Hollywood Ten, got sentenced to six months in prison for contempt of Congress and lost his job at RKO. Dmytryk said he knew they were doomed when he watched screenwriter John Howard Lawson's confrontational appearance in front of the committee, so he fled to England, where he made three films (Obsession, Give Us This Day and Christ in Concrete) before returning to the United States when his passport expired.

While serving his prison time Dmytryk decided to cooperate with the committee, testifying in 1951 about his brief membership in the Communist Party and naming names; he said it was pressure from Lawson and others that had made him include what were considered communist elements in his films – like the scene in Tender Comrade where Rogers pitches car-pooling and ride-sharing to her co-workers at a war plant. Dmytryk maintained years later that his stint in prison prevented him from suffering the same lingering hostility and resentment that would hound a director like Elia Kazan for the rest of his career. He spent a brief period back in b-pictures before Stanley Kramer gave him another break in the form of The Caine Mutiny, released the same year as Broken Lance and a box office smash.

Dmytryk would arguably have a better act two to his career than his act one, directing prestige pictures like The Left Hand of God (1955), Raintree County (1957), The Young Lions (1958), Walk on the Wild Side (1962), The Carpetbaggers (1964) and Anzio (1968). He was one of the last studio directors still working steadily in the '70s, but he retired from movies at the end of the decade, spending his last twenty years teaching and writing books about screenwriting and film editing.

It's still hard to talk about the Hollywood blacklist seven decades later; overall it was a gross violation of the First Amendment, especially just a few years after the political and economic upheaval of the Great Depression and the wartime partnership with Soviet Russia. There were, of course, real security threats to the country with Soviet agents in government, the atomic program and the secret services, but it's easy to dismiss the fight against the Red Menace in Hollywood as a combination of studio union-busting and the culling of talented competition by jealous writers, directors and stars.

Careers were definitely destroyed, but many would resume, albeit after a longer interruption than Dmytryk's, sometimes enhanced by opposition to HUAC as the industry gradually filled with talent and executives hostile to the committee and, later, McCarthy. You can, of course, dismiss someone like Dmytryk as an opportunist who played his cards right, but as early as 1976, when he was interviewed for the blacklist documentary Hollywood on Trial, Dmytryk said that there was a reverse blacklist in effect in the industry: "I think some of the fellas back then who were on the reactionary side are having a hard time finding a job now." At this point it's worth evoking one of the basic rules of Hollywood, which is that no matter what side you're on, assume that people are acting with the worst intentions.

When the dust clears and the clock rolls backward we see Spencer Tracy on horseback – the owner of the Devereaux Ranch, fully in charge. Matt Devereaux is a hard man, hardest of all on his three oldest sons, who he works relentlessly for the wages of hired hands, resisting pleading from both Ben and Joe to give them more responsibility. This lack of opportunity inspires Denny and Mike to turn cattle rustler, stealing some of Matt's herd before being caught trying to alter the brands; two other men are shot dead by Matt, Ben, Joe and Two Moons (Eduard Franz), Matt's native ranch foreman.

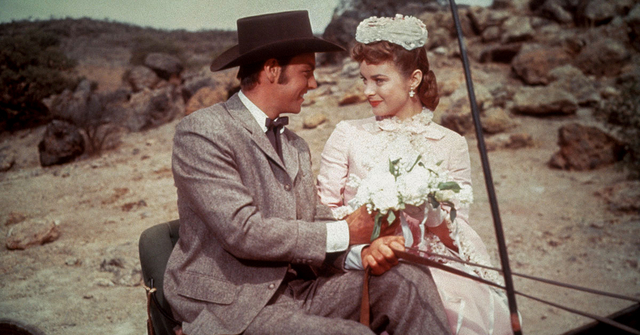

Enraged, Matt bans his two middle sons from the ranch, but Joe pleads for mercy, and ends up inviting them to a fancy dinner with guests that include the governor, Matt's lawyer and Barbara (Jean Peters), the governor's daughter, just returned from school out east. Joe knows that his father won't cause a scene there, but before the dinner ends there's a crisis on the ranch and all the Devereaux men are back in the saddle.

Broken Lance is far from the only western made during the '50s that's sympathetic to Native Americans, and it departs from the original story by making race an integral part of the plot, in the form of Matt's second wife (Katy Jurado) – Joe's mother. His first wife had died not long after he began homesteading, which is why he made his three oldest sons cheap labour while they built up the ranch. By the time Matt remarried, he had softened a bit with prosperity, and treats his youngest son with a gentleness and deference that angers his half-brothers.

It's understood that bigotry is always just under the surface in Broken Lance; out of respect to Matt's wealth and power, locals refer to Jurado's character as "Señora," pretending that she's Mexican and not Indian, playing the same game with Joe, his half-breed son, so long as he sticks to the ranch and avoids town. Tracy's character has a liberalism apparently born of pragmatism – he made an alliance early on with the local tribes that was beneficial to both sides, at least until civilization arrived on the doorstep of the ranch. (Just as the state remains mysterious, we're never told just what tribe Two Moons and the Señora belong to – Navajo, Apache, Yuma, Yaqui or Pima.)

Matt might be a harsh man, but he has no time for their prejudice, and becomes provoked into a rage when the governor admits that he's adamantly opposed to any romantic connection between Barbara and Joe. "It's born and bred in me," Marshall's character weakly explains to Matt, though for some reason he never passed it down to his daughter. When she makes him explain just what he and his mother have to live with, Wagner's Joe (tanned up by the makeup department for the role, naturally) ends up complaining more about his father's belligerent inflexibility.

"I thought you were worried about being an Indian," Barbara teases him. "You just don't like being Irish."

Dmytryk's reputation as an editor was what made his career, and it's showcased in the scene where Matt and his sons confront the manager and workers at the copper mine that's leased mineral rights from him. They're pouring tailings from the mine into a river that's poisoned Matt's cattle, and the confrontation turns ugly when the Devereaux men have to walk backwards to their horses with a wall of angry workers descending on them from the curved hill below the mine works.

Instead of the cavalry coming to save them, it's Matt's native workers on horseback, led by Two Moons; they beat the mine workers and pull down the works, which might have been considered rough justice back when the west was still wild, but now it just drags Matt into court on federal charges. He's contemptuous of the court and especially the prosecutor, and it's going badly for him until Joe decides to become the scapegoat, taking blame for calling in Matt's workers and leading the raid on the mine; he gets three years in prison, and Matt is shown riding his land, forlorn and heartbroken.

In Joe's absence Matt's other sons press their case against their father for more responsibility and a stake in the ranch; the old man refuses, admitting that while he never really built up his fortune for his sons to inherit, it's going to them in any case, and he'll run it his way until then. It was clear from the start that Widmark's Ben was going to be the story's villain – after all, why else cast Richard Widmark? – and he becomes more defiant with Matt, finally moving the old man to horsewhip his son in a rage that brings on a stroke.

Even here Dmytryk's movie defies expectations. Widmark's Ben might end up being the villain before the credits roll, but he's absolutely right to complain about his father's treatment, and as the opening of the movie demonstrates, he was also right to treat the ranch like a real business, getting the best prices for the cattle, leasing mineral and oil rights, signing on investors and selling land when capitalization is needed. Ben has been vindicated in the end, but it's not enough to prevent him from trying to banish and then murder the younger brother who paid for Ben's opportunities with his freedom.

There's nothing b-picture or oater about Broken Lance. It's as epic a western as was being made in the '50s, and becomes positively operatic in scenes such as the one where Matt tries to head off his sons as they ride into town to sign contracts he opposes. The sick old man's arm dangles loosely as he rides the land he and his horse know better than anyone else. By the time his sons find him waiting for them at a rise in the trail, he's already dead, upright on his horse, and Denny wonders aloud just how long he'd been that way, riding into battle like El Cid.

If Broken Lance reminds me of any picture made around the same time, it's more East of Eden than High Noon – a family drama with hints of melodrama, about parricide and fratricide at a time of historical upheaval. More than anything starring John Wayne or Randolph Scott, it hints at where the western would evolve. The current hit TV series Yellowstone feels like an updating and expansion of Broken Lance, with Kevin Costner as the tough patrician rancher John Dutton, Luke Grimes' Cayce in the role of Joe, and Ben's character divided between Kelly Reilly's Beth and Wes Bentley's Jamie. (Cole Hauser's Rip Wheeler is Two Moons, approximately.)

Is Yellowstone a western? It is, inasmuch as characters carry revolvers and wear Rockmount shirts and drink coffee by campfires in the shadow of mountains. It's also The Godfather, with chaps. If Broken Lance is a western, then Giant is as well, with a cordial agreement that King Lear can be a western, too, if you want it to be, because the magical thing about genres is that they don't really care about our definitions or rules.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.