It's not often you can remember the exact moment when something important entered your life – something that would abide from that moment on, influencing what you would do and be for the balance of your days. That moment, for me, was the first time I saw Topper on Magic Shadows, a TV show that ran on public television in Ontario starting in 1974.

The format of Magic Shadows was simple – a classic movie would be cut into four parts, a half hour shown from Monday to Thursday at 7pm, with Fridays reserved for an episode of an old movie serial like Nyoka and the Tigermen. The host was a man named Elwy Yost, whose name and memory is revered among movie fans of a certain age up here. He was the essence of geniality – bald and mustached, everybody's favorite uncle, his enthusiasm for the films he presented every weekday (as well as on his weekend show, Saturday Night at the Movies, where they'd play uncut) palpable to the viewer.

My friend Kathy Shaidle, the original author of this column, shared the same fond memories of "Uncle Elwy," having grown up watching him present films in Hamilton, the closest big city to my home in Toronto, where Magic Shadows was taped. He'd begin each week by breathlessly telling us how important the film we were about to see was, recapping the action each subsequent day and telling us who and what we should look for. It was probably Elwy who first uttered the words "screwball comedy" to me, in his introduction to Topper back on some Monday morning in the second half of the '70s, when Kathy and I settled in to watch Magic Shadows just after dinner in our respective homes.

It was Elwy who taught us that movies have history both onscreen and in their pedigree, and that they could be grouped into genres, whose rules were both fixed and fluid. He'd rhapsodize about the stars, but he was even more in awe of the directors, whose legacies he would celebrate in interviews with their collaborators – actors as well as writers, cameramen and composers. He really loved old movies, and did his best to convince us that we should love them as well. The theme song and animated opening to Magic Shadows is, as Kathy loved to recall, an achingly '70s artifact, but hearing it today overwhelms me with fond memories of settling in every night at the onset of prime time for a half hour of education and escape.

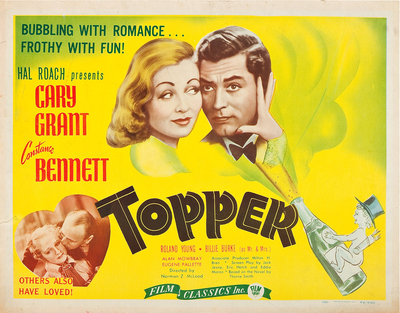

Topper is set, like so many screwball comedies, in the world of the wealthy, probably because – at least in the second half of the Great Depression – most Americans assumed that was the place where you'd suffer the least consequences for daft and irresponsible actions, like driving your powerful sports car with your feet. For that is the first thing we see George Kerby (Cary Grant) doing – in a tuxedo, no less – while his wife Marion (Constance Bennett), a tall slim blonde in a shimmering evening gown, handles the pedals.

The Kerbys, we quickly learn, are nuts – a wealthy couple who think nothing of leaving a party going full blast at their Long Island mansion to drive into Manhattan so that George can make a board meeting at a bank the next morning. With a whole night to kill, they progress through a series of night spots, with musical accompaniment moving from fox trot to Latin to Hawaiian, closing out the morning in some joint where Hoagy Carmichael is the piano player. They end up sleeping in their car outside the bank, which still doesn't prevent George from being late for his meeting.

The Kerbys might be nuts, but they're having a lot of fun – which is exactly what Cosmo Topper (Roland Young), the head of the bank, isn't having. A squinting mouse of a man (Beatrix Potter could provide a perfect caricature of Cosmo), he can't even luxuriate for an extra minute in his morning shower before the butler (Alan Mowbray, always reliable as a gentleman's gentleman) turns off the water and moves him on to the next item in the relentless itinerary that his wife Clara (Billie Burke) has devised for him.

After disrupting the board meeting with his habitual irreverence, George discovers that his wife has left their car empty at the curb and settled in to nap on the couch in Cosmo's office. Unlike her husband, Marion is fond of poor, pitiful, demoralized Topper, and it's clear that Cosmo has a schoolboy crush on the glamorous Marion; she leaves a handkerchief behind in his office, which Cosmo sniffs at in a reverie while trying and failing to dictate letters.

In the 1926 novel on which Topper is based, author Thorne Smith describes his titular character:

"Mr. Topper could excuse nature and the Republican Party, but not man. He was in institutional sort of animal, but not morbid. Not apparently. So completely and successfully had he inhibited himself that he veritably believed he was the freest person in the world. But Mr. Topper could not be troubled. His mental processes ran safely, smoothly, and on the dot along well signaled tracks; and his physical activities such as they were, obeyed without question an inelastic schedule of suburban domesticity. He resented being troubled. At least he thought he did. That was Mr. Topper's trouble, but at present he failed to realize it."

George is so put out by Topper and the bank that he decides to drive back to Long Island as quickly as their car – a 1936 Buick Series 60 roadster updated with a Chrysler chassis and body modifications by Pasadena coachbuilders Bohman & Schwartz – will take them on a country road shortcut. But the roads and the car are too much for George and they crash; the Kerbys pull themselves from the wreckage and sit down on a log, suddenly realizing their change of fate when they notice their lifeless bodies still lying next to the Buick.

"Funny, I don't feel any different," George tells his wife.

"No trumpets," Marion notes.

So they await the next step, wondering what the conventional thing to do might be.

"I don't know," Marion says. "We've never been conventional."

And so a quarter of the way through the film and the supposed leads are killed off, but it's worth remembering that the movie isn't called "The Kerbys" and a few weeks after the pair fade away on the log we're back at the home of the man the movie is actually named for. Cosmo has been troubled by the sudden death of George and Marion, and secretly had their car repaired and delivered to his home. He'd intended to sell it, but when his wife mocks him while he sits behind the wheel – "You look like a whatnot." – he ventures his first tentative rebellion and drives off in a huff, ending up blowing a tire and going off the road exactly where the Kerbys had crashed.

It's the perfect place for the ghostly couple to re-enter the world of the living, and the heretofore placid life of Cosmo Topper. They tell him that their place in heaven can only be obtained with a good deed, and they've decided that Cosmo will be it – while an invisible George replaces the tire (the special effects in Topper are remarkably good for 1937) Marion charms him into going along with their plan – at least long enough for a drive back into the city to their penthouse apartment where the ghosts can effect a change of clothes and refresh themselves with some bubbly. (As long as they assume their very palpable ectoplasmic forms, these ghosts are apparently subject to all the dictates of physics, fashion and appetite.)

The unsung star of Topper really is Roland Young. Behind his blinking and squinting and bottlebrush moustache, he does a beautiful job of portraying a man who has conformed to conventional expectations for far too long and, with just a few teasing prompts from a pair of carefree spirits (and a couple of glasses of champagne) starts to break loose in the most charming, pitiable way.

The one thing poor Cosmo wants to do more than anything else is dance and sing, even though his idea of a rousing tune seems to issue from some long-ago fraternity chorale, and his steps are spasmodic. The scene where Young's Topper asks Grant's George to indulge him while he dances quietly in his chair are hilarious, as Cosmo capers with timid abandon, his feet prancing while his arms firmly grip his chair.

The rules of the hereafter were apparently rewritten between the wars, and George and Marion's good deed involves turning Cosmo into a walking scandal, starting a brawl outside their apartment building and getting Topper hauled up in front of a judge. This being a Hollywood movie, Cosmo's brief incarceration garners the sorts of headlines ("BANKER AND BABE IN BRAWL") that get published in type only slightly smaller than that used to announce the outbreak of war or the death of a president.

At this point Grant's George momentarily exits the story as Marion takes over the heavy lifting of the Kerbys' good deed. The headlines have landed at the Toppers' breakfast table and while Clara is at first certain that their social standing is ruined, she quickly learns that Cosmo's scandalous reputation is a gift, as a deputation of society ladies descends on her, eager to add this apparent wild man and his wife to their guest lists. (The leader of the social register is played by no less than gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, just one entry in her vast filmography.)

Marion's ghostly invasion of a swanky lingerie store ends up with Cosmo carrying home a pair of lace pants in his suit jacket, only to be discovered by Clara, who assumes that he's involved with the babe from the brawl. Topper packs his bag and heads out with the spectre of Marion Kerby in his roadster, who steers him toward a swank seaside hotel for the night. At this point it needs to be understood that, for all intents and purposes, Cosmo has embarked on an affair with a ghost.

The farce is put into top gear at the hotel, with Marion getting Cosmo tipsy on Pink Ladies – a mixture of gin, applejack, lemon juice, grenadine and egg white that has thankfully not endured as a staple of classic cocktails. There's a lot of business with a bellboy (Arthur Lake) and the gravel-voiced Eugene Pallette as a hotel detective that escalates steadily from dance floor mayhem to a cordon of police sweeping the lobby looking for the babe from the brawl while George pelts them with light bulbs from a chandelier.

Grant's George rejoins the story in a huff, barging in on Clara at home in search of his wife, making the sorts of cross, threatening noises any man would make when chasing down an unfaithful spouse, spectral or not. It's a classic Grant scene, and Burke's aside to her butler through her tears after George leaves ("He's very handsome, isn't he?") would be echoed later in other Grant films. (Most notably the swooning line in North by Northwest uttered by the young woman who discovers Grant climbing through her window: "STOP! Stooooop..." It never fails to get a big laugh whenever I've seen the film.)

I knew that Cary Grant was a famous actor when I took in Topper over that week of Magic Shadows, over forty years ago, but I doubt if I'd seen any of his films apart from a distracted viewing of Operation Petticoat on a Buffalo TV station one Sunday afternoon after church. (I was told it was a war film. It sure didn't seem like a war film to me.) I remember my shock when I realized that Billie Burke was the same actress who played Glinda the Good Witch in The Wizard of Oz – it would be years before I understood that good actors worked a lot, especially in the studio system.

I assumed for many years that Constance Bennett, who really carries Topper along with Roland Young, was a screwball heroine as iconic as Carole Lombard or Claudette Colbert. It was a shock to discover that she really has only a couple of other roles in what might generously called screwball comedies (Merrily We Live and the sequel Topper Takes A Trip), and that her turn as Marion Kerby was done when her career was at the beginning of a steep decline. (Her younger sister Joan's career, on the other hand, was very much on the rise.)

It was Grant, of course, whose place in screwball history would be assured by Topper, which was released the same year as The Awful Truth, and before Bringing Up Baby, Holiday, His Girl Friday, My Favorite Wife and The Philadelphia Story. Maybe Elwy explained that to me at the time. I'm sure he would have known it.

Director Norman Z. McLeod is one of those footnotes to the story, despite a filmography that includes Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, Pennies from Heaven, It's A Gift and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. He would return to direct Topper Takes A Trip, along with Bennett, Young, Burke and Mowbray, but would luckily escape the regrettable Topper Returns, which only retained Young and Burke.

Apparently a young Lana Turner has an uncredited walk-on role in one of the nightclub scenes in Topper, but I've never been able to spot her in any of my viewings of the film.

It's difficult to describe to younger people how difficult it was to see old movies back in the '70s and '80s if you weren't prepared to comb the TV guide for late night screening or find the repertory houses that were thin on the ground, even in a big city like Toronto. In any case you had to know what you were looking for, and unless you owned one of the rare reference books that catalogued classic films, someone like Elwy Yost was your teacher and guide, inviting you to sit down with him and really appreciate these rare gems even if their prints had been scarred and faded from years of distribution to chop-happy TV stations. We'd have to wait a few years for VHS rental houses, never mind Turner Classic Movies, the Criterion Collection and cheap DVD reissues and box sets.

Magic Shadows stopped airing sometime in the '80s, in any case after I'd moved out on my own and lived without cable or even TV for nearly twenty years. Elwy didn't retire from Saturday Night at the Movies until 1999, though, by which point he had created one of the greatest archives of interviews with Hollywood legends and unsung heroes. His son Graham would fulfill his father's dream by becoming a Hollywood screenwriter and producer (Speed, From the Earth to the Moon, Band of Brothers, The Pacific, Justified, The Americans.) Elwy died in 2011.

About twenty-five years ago I found myself in an elevator at the film festival here with Elwy. I looked around and saw that everyone else in the elevator with us had the same bashful expression on their face. After a moment I broke the ice and told Elwy that he had been a big influence on me, and was probably the reason why I was even here, and the rest of the elevator joined in.

"Me too."

"Yeah, me too."

"Me as well. Thank you."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.