The Slap Heard 'Round The World preempted what should have been one of the most newsworthy moments of this year's Oscars: Elaine May receiving an honorary award from the Academy's Board of Governors. The normally reclusive May, who has never received a nomination for acting, writing or directing, confounded everyone by actually showing up, accompanied by Bill Murray, and giving a short but funny speech to the crowd at the Governor's luncheon, held on the Friday before the actual ceremonies.

"Are they all ex-award winners?" May asked, scanning the crowd. "Did you just come as guests? I don't know what else to say except enjoy your food."

These honorary Oscars are known as consolation prizes for people who've been overlooked amidst the campaigning and very political voting that produces winners, often for films or roles that don't deserve the praise. In May's case you could also interpret her honorary Oscar as a sign that she's been forgiven for Ishtar, the infamous 1987 bomb starring Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman that was her last credit as a director. It also provides an answer to the question: How many years does it take for the Academy to forgive you for making a bomb with two of their most bankable stars?

Thirty-five years. Just so you know.

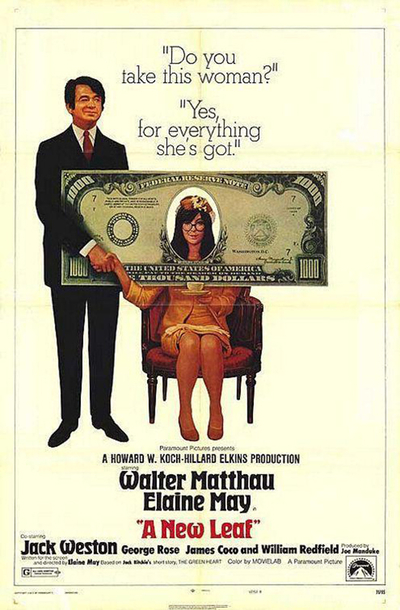

May's filmography as a director is short – just four films over sixteen years including Ishtar, the first of which was A New Leaf, a 1971 black comedy starring Walter Matthau as a newly penniless man who marries a rich woman, intending to kill her for her money. It used to be completely obscure, but has developed a cult following in the last couple of decades; last year Paste magazine called it "strange and special...one of the greatest romantic comedies of all time. In 2019 the Senses of Cinema website called it "a darkly funny romantic comedy of cross-purposes."

When we meet Matthau's Henry for the first time, he's anxiously waiting while men in white coats monitor beeping machines to diagnose the health of a loved one. After a long series of shots that heighten the tension and dwell on the grotesque faces of these technicians, we learn that the patient in question is Henry's car – a Ferrari 275GTB4 that, according to Henry, is in the garage two to three times a week, and needs a tuneup every few weeks. The problem, we're told over and over, is "carbon on the valves."

This particular front-engined Ferrari was already wildly valuable at the turn of the '70s, and at a Barrett-Jackson auction last year a very well-restored 1967 model sold for $2,475,000. It was already a running joke in the '60s that owning a sports car was the best possible way to subsidize the lifestyle of a high-priced mechanic; owners of the more democratically-priced but equally lovely E-Type Jaguar would share similar fiscal agonies thanks to their car's famously finicky electrics.

I have a friend whose vintage Porsche 911 could only emerge from winter storage after thousands of dollars in restorative repairs. I have another one whose love of high performance German coupes entails ongoing expenses that look more like an extension of the Marshall Plan. It all feels like a bit of period detail today though, as sports cars - and the men who drive them - are disappearing from all but the most high-priced streets of major cities – ones where traffic and speed limits prevent anyone from demonstrating the theoretical top speeds of the vehicles.

Henry is a man of taste and social standing, both of which are under threat from repeated messages from his lawyer, who struggles to reach Henry at his club, on his horse, and even in a private plane. The brutal fact is that Henry has been attempting to live the life of a man with $200,000 a year on an income of just $90,000 a year, and the money has run out. At first it seems like he's too dim to understand the basic economics of his situation, but then it becomes obvious that he's trying to ignore them, to the frustration of his lawyer, who has been shoring up this fantasy of independent wealth by selling off assets and even covering overdrafts out of his own pocket.

"I have given you $550 of my money for one reason," the lawyer explains to Henry. "Disliking you as intensely as I do, to be absolutely certain that when I looked back on your financial downfall, I could absolve myself completely of my responsibility for it."

As played by Matthau, Henry is also a pompous jerk, a bred-in-the-bone snob who cannot imagine living life in any reduced capacity. When he finally comprehends his situation, he goes on a tour of the highlights of his world – his tailor, the doorman buildings of the Upper East Side, his polo club, Lutèce, the New York Racquet Club – while whispering "Goodbye" over and over.

Back at his apartment, with its tastefully minimalist furnishings and collection of abstract art and African sculptures, he asks his butler Harold (George Rose) what he would do should Henry lose his money. Harold respectfully replies that he'd give his two weeks' notice, but adds that, as Henry is both unwilling and unable to get a job, the only course of action left is to find a rich woman to marry. Initially repulsed by the idea – whatever vices Henry has, carnality doesn't seem to be one of them – he quickly warms to it, but only after adding his own innovation that he'll kill her for the inheritance.

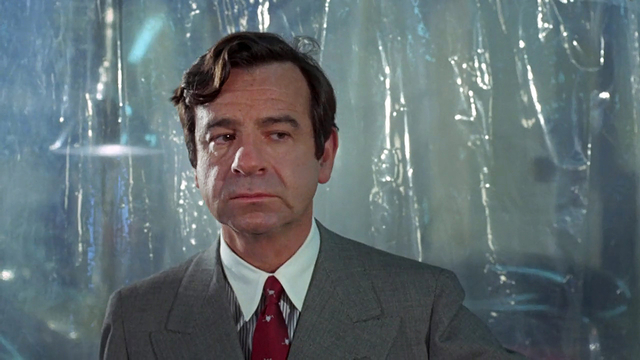

Walter Matthau is known today for two roles – Oscar Madison in The Odd Couple (a role he originated in Neil Simon's play and reprised for the 1968 movie) and as Morris Buttermaker in The Bad News Bears (1976). He's one of those actors who seemed to have been born middle-aged, but he spent the first half of his twenties as a radio-gunman in Europe, in the same U.S. Army Air Force bomber group as Jimmy Stewart, before returning home to study acting in New York City.

Early roles as villains in films like The Kentuckian and King Creole led to a breakout role in Elia Kazan's A Face in the Crowd (1957). By the '60s he was a reliably doleful, often rumpled presence in comedies and dramas before an onscreen partnership with Jack Lemmon in Billy Wilder's The Fortune Cookie (1966) led to real stardom, and an unlikely pair of romantic leads in two 1969 films, Hello, Dolly! And Cactus Flower. This was the actor that Elaine May cast as Henry, a role that had Matthau play slightly against type as a fussy, old money aesthete.

To manage a troll through the co-op apartments and summer homes of society for a rich bride, Henry needs a grub stake to hold off his debtors, and he turns to his uncle and former guardian, Harry (James Coco), who we first glimpse in profile, a huge, laughing face looking like it's about to swallow the supplicant Henry. Uncle Harry lives in Bourbon splendour, a spiteful gourmand in a smoking jacket who has learned – like most people – to detest his nephew.

He reminds Henry that although he is bequeathing his personal fortune to Radio Free Europe (one of many gags that May spikes her script with, and one that I'm not sure would get the same laughs today) he will give Henry a loan on usurious terms, sure to lead to his final ruination once he fails to find a woman with the appropriate combination of wealth and dimness.

Henry's first quarry is a rich widow caught up in the spirit of the sexual revolution, who intones mantras about her revivified sexual energy to the very nearly asexual Henry. She's a more than enthusiastic candidate for marriage, but when she corners him in the throes of apparent heat and begins to remove her bikini top, Matthau's Henry bolts with a panicked cry of "NO! Don't let them out!"

Henry is almost out of time when he comes across Henrietta Lowell at a country house party. (During a round of introductions he's introduced to a couple with the surname Hitler. "You aren't by any chance related to the Boston Hitlers?" he inquires; another little gag of May's that you miss if you blink.) She's a botanist who teaches at an undistinguished school and heiress to a huge fortune. She's also a cringing wallflower, a mousey klutz who can't hold onto a cup without spilling the contents on to the hostess' prized Aubusson rug, her glasses falling off her face, forever unsure about what to do with her purse and gloves as if they've just been handed to her.

She is, as Henry says to himself, "perfect," though everything about her irritates him. She has "no spirit, no wit, no conversation and she has to be vacuumed every time she eats." Worst of all Henrietta's idea of a fine vintage is Mogen-David Extra Heavy Malaga Wine with soda water and lime juice. This can be endured, but only for a short while.

It's been debated that May had no intention of writing, directing and starring in her first film, but her decision to take on the role of Henrietta is interesting. When A New Leaf came out, Elaine May was still famous for being half of the comedy duo Nichols and May nearly a decade previous. Her partner, Mike Nichols, was by now famous as the director of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Graduate, but May's career after the dissolution of the duo in 1961 had been slower to develop.

It's a ritual to celebrate Nichols and May, even for people (like myself) who weren't even alive when they were a comedy sensation. A brilliant pair of writers and improvisers, they created a unique two-handed comedy that was seemingly everywhere in the late '50s, on records and TV, on the stage and even in subtly wry commercials for companies like Pontiac. Their obvious specialty was the relationships between men and women – married couples, horny kids, co-workers, mother and son – and the astonishingly versatile May could effortlessly portray any age, class or social background.

With the aid of managers and handlers, May as half of Nichols and May had an attractive, even glamorous image – a mature, intelligent and vivacious woman very much the equal of her partner; in old photos and videos she evokes actress Anne Bancroft or the painter Helen Frankenthaler. (I've always found it interesting that Nichols ended up casting Bancroft as Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate; would the movie have been as good, or even better, if he'd cast his old partner? The two women were only born a year apart.) In her first movie role in Carl Reiner's 1967 comedy Enter Laughing, she plays a sultry bohemian seductress. Offstage and off screen, however, she was apparently more casual and unkempt, so it's hard not to speculate how much of herself May put into Henrietta.

A New Leaf shares a broad, even Brechtian comic aesthetic with a lot of films made in the '60s. You can argue that this goes back to the Marx Brothers – fully acknowledged as comic geniuses by filmmakers and actors in the '60s – but it shares a period-specific edge and aggression with films as different as Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove, the James Coburn vehicle The President's Analyst (1967) or Alan Arkin's movie adaptation of Jules Feiffer's Little Murders (1971).

All over Neal Hefti's soundtrack for her film, May has sound effects – twittering birds, electronic bleeps – superimposed to undercut what might pass for naturalism, and actors are given odd bits of business, like the messenger who intercepts Henry while he's riding to deliver a message from his lawyer, only to have his horse canter and then collapse.

The biggest obstacle in the way of Henry marring Henrietta is her lawyer, Andy McPherson (Jack Weston), whose office wall is adorned with a huge sculpture of an 1878 Morgan US silver dollar. He's been trying to marry her for years, and when he joins forces with Uncle Harry he almost convinces her that Henry was only interested in her money, until Henry improvises brilliantly and tells her that he took the loan from his uncle to settle his affairs before he killed himself, and it was only meeting Henrietta that restored his will to live.

Henry is barely able to make his way through the wedding ceremony – Matthau's legs become feeble as he walks the few short yards up the aisle – and the honeymoon is notable mostly for a hilariously awkward wedding night where Henry has to help his wife find the appropriate arm and neck holes in her "Grecian" nightgown. Still, Henry is able to brazen his way through all of this farce and perfidy thanks to his sole quality as a man – what his uncle describes as "an urbanity born of disinterest."

Back home, Henry prepares to move into Henrietta's palatial family home, only to discover that her household staff is run on principles that his butler Harold describes as "very democratic." Her chauffeur is more likely than not to forget to pick up or drop off his employer, so she's learned that it's easier to take the bus, and the housekeeper Mrs. Traggert (Doris Roberts) constantly winks at him from the moment they're introduced.

Aided by the superhuman efforts of Harold, Henry discovers that the running of Henrietta's household was wholly organized by Andy, who has been taking massive kickbacks on salaries and budgets. Harold is inspired by the sure knowledge that there are few job openings for gentlemen's gentlemen if he has to leave Henry's service, but Henry is motivated to overcome his lavish idleness when presented with Andy's corruption and the staff's eager willingness to take advantage of Henrietta's timid and trusting nature. It wasn't surprising to see how easily May skewered the pretentions and entitlement of the upper classes – a common theme in American culture since before the Gilded Age – but she's just as scathing in her depiction of the loutish, indigent demos – yet another gallery of grotesques - who have infiltrated Henrietta's home with Andy's connivance.

If it wasn't obvious already, A New Leaf shares with its male protagonist a casual but wide-reaching misanthropy that – my theory, but I stand by it – is at the heart of all really great comedy, but is rarely expressed so openly. May herself would be constantly criticized for not assuming the usual political stances; in 1973 feminist critic Marjorie Rosen would call her "an Uncle Tom whose feminine sensibilities are demonstrably nil."

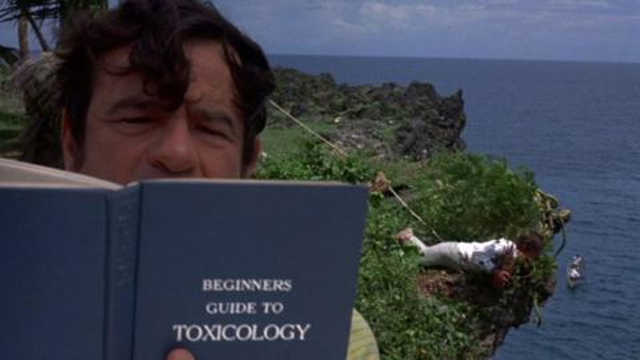

After the honeymoon, Henry has to get down to the brass tacks of disposing of his wife, but her banishment of pesticides from the garden shed on the estate in favour of organic principles deprives him of the easiest weapon at hand. He decides instead that it would be simpler to arrange an accident while they're canoeing in the Adirondacks, just after her discovery of a new species of fern on their honeymoon – a species that she names after him. (Just in case you were wondering where the film gets its title.)

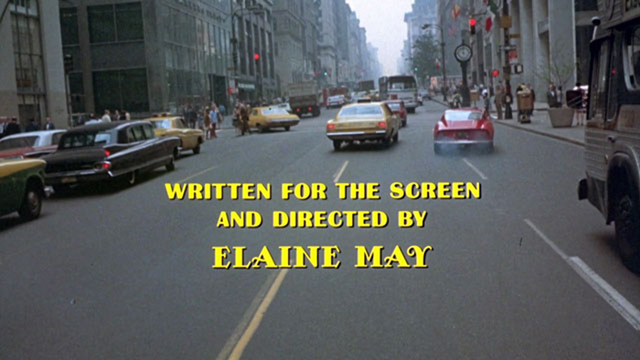

May's first film did not enter the theatres easily. She went wildly over budget - $4 million on a $1.8 million budget; this would happen again on subsequent films like Mikey and Nicky and Ishtar – and she handed in a rumoured 3-hour cut of the film to Paramount that was closer to the original story by Jack Ritchie, in which Henry actually killed Andy and another character and got away with it.

No less than Robert Evans took the film away from May despite a contract promising her final cut, and when she took the studio to court, they screened their shorter edit to the judge, who found it hilarious and ruled in their favour, setting a precedent for studios interfering legally with directors' work. With this information in mind, it's easier to understand the change of pace and tone that happens in the last third of the film, before Henry and Henrietta literally walk off into the sunset.

A New Leaf ended up making a million dollars over the final budget and opened to excellent reviews – both Roger Ebert and Vincent Canby praised it, sharing the use of the word "cockeyed" to describe May's film – and it allowed her to make The Heartbreak Kid (1972) with Charles Grodin and Cybill Shepherd, from a script by Neil Simon. She would be the only female director working in Hollywood in the '70s, which naturally made her something of a target. Mikey and Nicky, starring Peter Falk and John Cassavetes, followed, then writing gigs on Heaven Can Wait, Reds, Tootsie and Labyrinth, and finally the calamity of Ishtar.

Elaine May would appear just a handful of times as an actor, in California Suite (1978), In the Spirit (1990) and Woody Allen's Small Time Crooks (2000). She was more active as a writer, credited with work on Dangerous Minds (1995) as well as Mike Nichols' The Birdcage (1996) and Primary Colors (1998), though it's an open secret that her work is uncredited on countless other scripts, with a reputation for fixing stories that other writers have abandoned. And now, I hear, there's a growing movement to reclaim Ishtar from Hollywood's ash heap, along with other studio-destroying flops like Cleopatra and Heaven's Gate. Along with her honorary Oscar, it is a fitting last laugh for someone who, based on the work she did in her prime, would be lost in Hollywood today.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.