On the surface, Budd Boetticher's The Tall T looks like any other western. It's set in the arid desert of the American southwest, on the eve of the arrival of the railroads, in a place full of vast distances between settlements, themselves little more than collections of ramshackle wooden buildings offering basic services and goods. The stagecoach is still the main form of transportation between these villages and larger towns and cities, and the spaces they traverse are full of outlaws ready to kill. Heinz Roemheld's score has the usual sweeping, epic melodies and clip-clop rhythms.

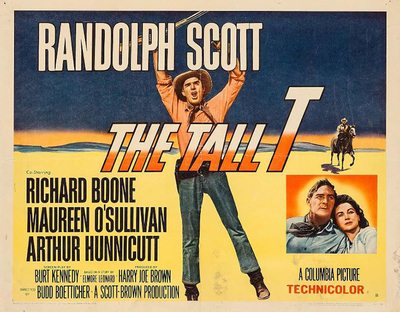

And at the centre of it all is a stoic, upright man who embodies heroic virtue either by choice or circumstance – in this case Randolph Scott, western veteran and probably the greatest star of the genre, even if you don't take John Wayne off the table.

The film was released in 1957, the second in Boetticher's "Ranown Cycle" – seven films made between 1956 and 1960, starring Scott and mostly made with writer Burt Kennedy and producer Harry Joe Brown. They're probably the last great classic westerns made before the arrival of the spaghetti western set the whole genre on its darker, revisionist path that continues till this day.

The titles roll over an indelible landscape – the Alabama Hills outside Lone Pine, two hundred miles from Los Angeles in the Sierra Nevada mountains. With its incredible vistas of sand-worn boulders, it was the sort of place that directors went to if their budget allowed them to stray beyond the backlots, Topanga, Franklin Canyon and the movie ranches, but didn't have cash for location shooting in Arizona, Utah or New Mexico. It was a favorite of western directors going back to the '20s, and the town of Lone Pine is the home of the Museum of Western Film History.

Out of this landscape comes a single man on a horse – Scott's Brennan, a former ramrod and bronco buster who's set out on his own, ranching far out in the hills, alone. He's on his way into town to try to buy a seed bull, and passes through a station on his way. He's friendly with the widowed station manager and his boy, who's grown up in this isolated place, and idolizes men like Brennan.

Much of the gentle business between the three happens around the station's well, which doesn't at all seem ominous at the time.

Brennan arrives in town, runs into his pal Rintoon, the stage coach driver and source of much of the film's comic relief, played by Arthur Hunnicutt as a flintier Gabby Hayes. He makes it to the ranch owned by Tenvoorde, his old employer, who makes him an offer – if he can ride the bull of his choice, he can keep him. If he doesn't, Brennan loses his horse. At this point we get some idea why Tenvoorde owns a ranch full of hired cowboys and Brennan works alone in the distant hills.

Cut to Scott walking down a dusty road, carrying his saddle and guns. He flags down a passing stagecoach, driven by Rintoon, who's been hired by Willard Mimms, bookkeeper to the local copper baron, now a man of means after marrying Doretta, his boss's old maid of a daughter, a woman we're supposed to regard as plain, even homely, based on the comments of every man who sees her.

Doretta is played by none other than Maureen O'Sullivan, the most famous Jane to Johnny Weissmuller, the most iconic Tarzan. By no means an unattractive woman, O'Sullivan has to do a bit more than the usual "Oh Miss Smith you're lovely without your glasses" Hollywood beauty downgrade. The usual glamorous makeup treatment is foregone, of course, but O'Sullivan really sells Doretta's dowdiness with a sagging, beaten posture and pinched, anxious expressions.

Over Willard's protests, Rintoon agrees to give Brennan a ride to the station, but when they get there the manager and his boy are nowhere to be seen. From the shadows a voice tells them to drop their weapons. Frank (Richard Boone) and his men are hijacking the stagecoach, which they've mistaken for the regular coach carrying the mail. Brennan throws his gun and saddle into the dirt, but Rintoon goes for the shotgun at his feet, and gets blown off the coach by Chink, Frank's gunslinger accomplice, played with customary laconic menace by Henry Silva, a reliable villain in any genre.

Brennan asks Frank where the station master and his boy are. Frank indicates the well, which is where he and the Mimms are destined until Willard bargains for his life by selling Frank on a scheme to ransom Doretta for $50,000 of the copper baron's fortune. For reasons of his own, Frank decides to keep Brennan alive, but not before telling him to drop Rintoon's body down the well. Less than a third of the way into Boetticher's extremely economical 78-minute film, the comic relief has been killed and the tone has changed palpably.

The Tall T was released at a pivotal period in the history of the western. The genre was in decline, not for the first time, and the advent of television was changing how and where westerns got made. In their seminal book The Western from Silents to the Seventies, George N. Fenin and William K. Everson noted that the first four years of the '50s saw the near-total decimation of the western "B" picture and the serial, with once-bankable series abandoned and western stars put literally out to pasture.

Television, with an insatiable hunger for material and nowhere near enough of its own programming to fill it, licensed westerns from the catalogues of the studios to fill air time – first the cheaper product of poverty row studios, then more slickly made pictures from the majors when the oaters became hits with TV audiences – mostly kids watching them after school or on weekends and summer vacations when adults were at work or otherwise occupied with the postwar economic boom.

This gave birth to hit western TV series that began production in the '50s and, like Bonanza and Gunsmoke, sometimes ran until the '70s. They became a reliable source of income for new directors as well as old ones made redundant by the "B" western shutdown a few years earlier: Budd Boetticher took a break while filming the Ranown Cycle to direct the first three episodes of ABC's Maverick, which made a star out of James Garner.

The studios still made westerns, but their budgets contracted considerably, and it showed onscreen. "Mobile camera work was reduced to a minimum," write Fenin and Everson, "resulting in long static dialogue takes devoid of movement or intercutting. Casts and even livestock were reduced to skeleton forces, and a maximum use was made of stock footage." The result is a picture like The Tall T, which feels stark and underpopulated, and really just devolves to a story about five people marooned in an arid, sun-baked landscape, vaguely evoking the plays of aggressively minimalist writers like Samuel Beckett or Harold Pinter.

Frank takes his captives to his hideout – a mine head cave carved into the side of a pile of rocks in the midst of a sea of similar piles of rocks. Doretta doesn't know about the plan her husband has hatched with Frank until he rides off to deliver the ransom note to her father, accompanied by Frank's other associate, Billy Jack (Skip Homeier, a former child actor who would later work mostly in television, with roles in Combat! and Star Trek before playing the judge in the Manson trial in Helter Skelter).

Frank and his gang might be murderous outlaws, but they hold a man like Willard Mimms in contempt – a soft-handed coward who'll sell his wife to save his skin. When he returns with Billy Jack and the good news that the ransom will be paid in a day, Frank magnanimously tells him that, since he's done his bit, he can get back on his horse and head back to town. Willard declines an offer to say goodbye to his wife and, eagerly promising that he'll make sure the ransom exchange goes smoothly, rides away, but Frank tells Chink to shoot him off his horse before he's out of sight.

The key departure Boetticher's film takes from the average western is among the first intimations of the darkening tone and moral uneasiness the genre was about to assume. It's embodied in Richard Boone's Frank; he's a villain to be sure, but he has a moral code, and he takes a liking to Scott's Brennan, seeing him as a version of himself if his life had turned out differently, with the same ambition for a home and some land to work. Like most villains, he considers himself a victim of circumstances, and when Brennan points out that he's who he is because of choices he made, the outlaw testily reminds him just who has the upper hand.

Boone was one of several actors whose roles as villains in the Ranown Cycle led to stardom in their subsequent careers – actors like Lee Marvin (Seven Men From Now), Lee Van Cleef and James Coburn (Ride Lonesome) and Claude Akins (Comanche Station). His Frank has enormous charisma and a huge, boisterous laugh – he's the only person in the story who sees the humour in their situation, and he's eager to talk to Brennan to get a break from the crude banter about women and booze he's forced to hear from Chink and Billy Jack.

He makes a point of letting Brennan know that, even if he has a price on his head, he's never actually shot a man, preferring to leave that to "animals" like his associates. Boetticher does his best to make us like Frank in spite of everything, and to create a strange bond between him and Brennan, which only makes the final scene more powerful.

Oscar "Budd" Boetticher Jr. was a fascinating man. Even amidst legendarily macho western directors like William Wellman and John Ford, Boetticher's life story scored major alpha male points. He was born in Chicago but adopted into privilege; his adoptive father was head of a hardware empire, his much younger wife a great beauty. The only interest father and son shared was horses, and after a car crash ended a promising career as a star college athlete, he ended up in Mexico City, where a chance afternoon watching a bullfight saw him train as a matador under legendary bullfighters like Carlos Arruza.

He ended up in Hollywood working on the crew of films like Of Mice and Men, where another chance encounter with director Rouben Mamoulian got him assigned as technical advisor on Mamoulian's bullfighting melodrama Blood and Sand. This lucky break saw him promoted to assistant director on movies like The More the Merrier and Cover Girl, and finally to director on "B" films like the Boston Blackie picture One Mysterious Night.

A stint in the navy making documentaries and service films interrupted his Hollywood career, and after returning he ended up working for poverty row studios like Eagle Lion and Monogram. John Wayne gave him his second big break, signing him to direct The Bullfighter and the Lady for Batjac, his own production company. He signed to Universal to make a series of western and adventure films, and then made another bullfighting picture, The Magnificent Matador, starring Maureen O'Hara and his friend Anthony Quinn.

Boetticher made the first picture in the Ranown Cycle, Seven Men from Now, for Batjac and Warner Brothers, before returning to Columbia for all but one of the last six. (Westbound, from 1959, was made for Warner.) The pictures were a hit, but the work was on television by then, and Boetticher directed episodes of Death Valley Days, The Rifleman and Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theater.

He made one film noir, The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond (1960), before heading to Mexico with his new wife, Debra Paget, to begin work with what was supposed to be a biopic of his teacher, Carlos Arruza. This turned into an ordeal for the director, who endured divorce, illness, bankruptcy and time in both jail and an asylum before finally finishing Arruza as a documentary in 1968. He made one last western, A Time for Dying, with Audie Murphy, and then lost his job directing Two Mules for Sister Sarah to his friend Don Siegel after providing the story for the film. Even worse, thanks to money problems and Murphy's death in a plane crash, A Time For Dying wouldn't end up being widely released for another twelve years.

Apart from a 1985 documentary about breeding horses for the bullring and a role in Robert Towne's Tequila Sunrise (1988), Boetticher's career in Hollywood was over. When the revised and expanded edition of The Western from Silents to the Seventies came out in 1973, Boetticher was virtually forgotten, and neither he nor any of his films get mentioned in the book.

While he may have been forgotten in America, in France a generation of cineastes were formulating the auteur theory and enthusiastically reappraising the work of overlooked directors like Fritz Lang, Robert Aldrich, Nicholas Ray – and Boetticher. By the 1980s, American directors like Martin Scorsese and Taylor Hackford were enthusiastically singing his praises and in 2008 a box set of five of the seven films in the Ranown Cycle was released by Sony with introductions and commentary by Scorsese, Hackford and Clint Eastwood – seven years after Boetticher's death.

From the moment he meets Frank, Brennan knows that he's going to die; it's the first thing the two men talk about. So for the rest of the film he prepares himself for a chance at survival, realizing that he stands a better chance if he can get Doretta to help him. This means rebuilding the woman's sense of self-esteem from the low point after she watched her husband – a man she knew didn't love her, saw her as a meal ticket, and whom she married just so she wouldn't be alone – get gunned down by Chink. "I'm not going to be shot in the belly because you don't care about yourself," Brennan tells her during their long confinement in the cave.

The only people who treat Doretta with any compassion are Frank and Brennan, but it's Brennan's job to help her get over the obvious tragedy of her life, unloved by both her father and her husband, to know that losing the latter is hardly a real tragedy: "So what have you lost besides a little pride."

Their opportunity comes when Frank rides off to collect the ransom, leaving Brennan behind with the two young gunmen. They're easily manipulated by the older man, who convinces Chink to head off to check on the ransom meeting, leaving Billy Jack behind to fall into a trap set by Brennan with Doretta as bait, when Brennan tells the outlaw that his two associates have been visiting the woman at night behind his back.

Doretta does her best to try and seduce the young man, just long enough for Brennan to rush into the cave and struggle with him for his shotgun; the two men have its barrel wedged between them when Brennan reaches for the trigger. The camera cuts away, but it's obvious that the young outlaw's death wasn't the usual clean shot to the torso followed by a swoon and a fall, but the discharge of the gun point blank into his face.

"Don't look," Brennan tells Doretta.

It takes a bit more work to arrange an ambush for the more skilled Chink, but Brennan manages to get the drop on him as well. Frank returns to find his associates dead and Brennan holding a gun on him. He knows that Brennan probably doesn't have the stomach for another killing, especially in cold blood, so he drops the money and his gun and walks calmly to his horse, explaining that he knows he's beaten and will just ride away, out of their lives.

Just out of sight, however, he reconsiders, pulls a rifle from his saddle holster and charges back at Brennan and Doretta. But he's not much of a gunman, as he's already admitted, and ends up riding into Brennan's bullets, blinding Frank, knocking him off his horse and sending him staggering around the camp screaming and clutching his face, in and out of the cave, before collapsing dead in the sand. It's neither a clean nor a dignified death, and coming after the bodies in the well, the coward dying with a bullet in his back and the boy with his face blown off, it gives The Tall T a grimness that we couldn't anticipate from those first scenes.

From this point it's a short stride through the sand to Sergio Leone and the Dollars Trilogy, Sam Peckinpah's "Ballet of Blood," and antiheroes like Django, Trinity, Rooster Cogburn, the Stranger in High Plains Drifter and William Munny in The Unforgiven. Quite without anyone noticing, and with none other than Randolph Scott presiding over the action, something new was being added to the western, which would never be the same.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.