If you heard Friday's Hundred Years Ago Show, you'll know we marked the centenary that day of the sudden death of a great entertainer at the age of forty-seven: March 4th 1922. Bert Williams is a somewhat faded name in 2022, as any stage performer who died a hundred years ago would expect to be. But his most famous song is still known, and still sung:

That's Randy Crawford singing a song written in 1905. Just shy of a century later, it was one of the last songs Johnny Cash ever recorded:

It predates jazz; it's vaudeville, a theatre song, a number designed to be played to a crowd and get a reaction, as it did. Bert Williams' biggest hit was a paradox – a number about a forlorn non-entity that was the biggest showstopper on the New York stage for over a decade:

When life seems full of clouds an' rain

And I am filled with naught but pain,

Who soothes my thumpin' bumpin' brain?

Nobody.When winter comes with snow an' sleet

And me with hunger an' cold feet

Who says "Here's two bits, go an' eat!"

Nobody...

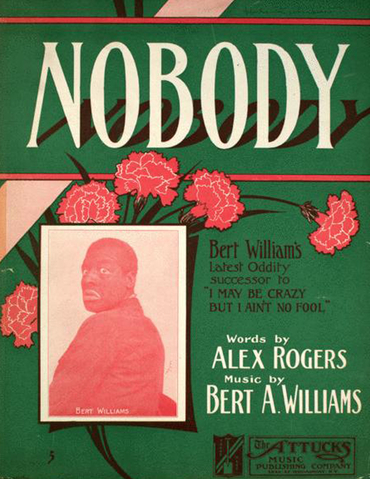

Bert Williams was the most popular comedian in the country, and he was "African-American", as the PBS Broadway TV series insisted on billing him. Aside from the anachronism, it's an even odder designation for a fellow from the Bahamas – a British West Indian, if we're going to bandy hyphenated identities, and like so many from the English Caribbean one who prospered in America. He'd written "Nobody" with Alex Rogers, a black writer who had hits with "coon songs" like "Bon Bon Buddy (The Chocolate Drop)" and made a few records of his own after Bert Williams' death. But neither man ever had another song the size of "Nobody". Williams introduced it on stage in 1905 and the first record was made by Arthur Collins, one of the biggest recording stars of the era:

The reviewer for the August 1905 Edison Phonograph Monthly loved it:

The song fits Mr. Collins like a glove. The story is of a coon for whom nobody does nothing, therefore he does nothing for nobody.

Arthur Collins' version did okay, but it was Williams' song and his recording (less mannered than Collins') was a smash, the biggest-selling record in America for over two months:

In 1913, a second recording was a smash all over again:

As Bert Williams wrote in American Magazine in 1918:

Every comedian at some time in his life learns to curse the particular stunt of his that was most popular. Before I got through with 'Nobody' I could have wished that both the author of the words [Mr Rogers] and the assembler of the tune [himself] had been strangled or drowned or talked to death. For seven whole years I had to sing it. Month after month I tried to drop it and sing something new, but I could get nothing to replace it, and the audiences seemed to want nothing else.

So he tried the obvious one word follow-up – "Somebody":

After that Williams moved on to "Constantly", "Unexpectedly" and "Not Lately", and they did okay. But he knew what his fans wanted. Audiences on Broadway and across America never tired of hearing him sing:

I ain't never done nothin' to Nobody

I ain't never got nothin' from Nobody no time

And until I get somethin' from somebody sometime

I don't intend to do nothin' for Nobody no time...

Insofar as one can tell, and ebonics professors notwithstanding, nineteenth-century colored folk didn't talk like that. White minstrel acts and vaudevillian comics created the lingo, and it became so popular that the savvier Negro entertainers figured out (as Ben Vereen would put it many years later) "Wait a minute, I can do me better than they're doing me."

That was certainly true in Williams' case. He came to America as a teenager, educated and well-spoken and, like many West Indians, light-skinned. He'd hoped to make a living on the legitimate stage – Shakespeare, Molière, Ben Jonson. But he wound up playing banjo in a minstrel show and then hooked up with George Walker to form a blackface double-act. That's right: Their faces were black, but they still had to do the full Justin Trudeau. That's to say, they smeared burnt cork on themselves so that they looked more like "stage coons" – as, say, in the popular act "The Hebrew and the Coon", in which the Hebrew was the genuine article and the Coon was Al Jolson in blackface: two Hebrews in assorted shades. With Williams and Walker, George Walker was the sly, natty dandy and Bert Williams was a shabby schlub with a shuffling gait and a mournful delivery that audiences loved. He brought a genuine pathos to the material:

Last Christmas Eve about daybreak

I was in that railroad wreck

Who hauled the engine off my neck?

Nobody, not a livin' soul...

"Nobody", at one level, is the rueful fatalism of an entire race, but, at another, is one man's transcendence over it. That's what gives it its power. Nina Simone, who had a very shrewd sense of material, could still tap into that in her version of the song half-a-century later:

Williams and Walker headlined the first full-scale Broadway musical written and performed by a black cast at a major house, In Dahomey (1903), and, when ill health forced Walker out of show business in 1909, Williams was signed by Florenz Ziegfeld for the Follies and became the first black entertainer to headline with a white ensemble.

Not that the latter were happy about it. Most of them threatened to quit, until Ziegfeld told them, "I can replace every one of you, except the man you want me to fire."

As Williams himself once said:

I have noticed that this 'race prejudice' is not to be found in people who are sure enough of their position to be able to defy it. For example, the kindest, most courteous, most democratic man I ever met was the King of England, the late King Edward VII. I shall never forget how frightened I was before the first time I sang for him. I kept thinking of his position, his dignity, his titles: King of Great Britain and Ireland, Emperor of India, and half a page more of them, and my knees knocked together and the sweat stood out on my forehead. And I found – the easiest, most responsive, most appreciative audience any artist could wish.

And, as the question came up again and again, he learned to answer it this way:

People sometimes ask me if I would not give anything to be white. I answer, in the words of the song, most emphatically, 'No.' How do I know what I might be if I were a white man? I might be a sand-hog, burrowing away and losing my health for eight dollars a day. I might be a street-car conductor at twelve or fifteen dollars a week. There is many a white man less fortunate and less well equipped than I am. In truth, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have often found it in inconvenient – in America.

Williams became a huge somebody singing about being a nobody. Today, when his glorious career comes up, he's supposedly a nobody again – the name is usually prefaced by "the now all but forgotten figure" or some such. Yet, compared with the big white stars of the day, he still resonates, the subject of books, plays, revues every few years, a kind of Broadway Jackie Robinson, a curiosity because of his color. That seems somewhat reductive, a way of imposing contemporary racial obsessions on the past. It would be more interesting to explore why later black entertainers (Stepin Fetchit et al) kept the tics and mannerisms of Williams but lost all the pathos. Or why an entire tradition of black artistry seems to have all but vanished. By comparison with three generations of black musicians from Will Marion Cook and Scott Joplin to Nat Cole and Duke Ellington, Tupac Shakur and the like sound like minstrel acts on crack: the more "authentic" they think they're being, the more burnt cork they're burning through.

As for Williams, he bore with grace vicissitudes they'll never know. There's a story that he once walked into a midtown bar and asked for a martini. And the bartender looked at the black man and sneered, sure, no problem, that'll be a thousand bucks. And Williams reached into his wallet and plunked down five thousand-dollars bill on the bar. "I'll have five," he said.

It's a great story. But I think there's more truth and pain in another anecdote: If you're a gifted and famous man, the small routine slights of humdrum daily encounters must sting even more. Imagine (to return to Williams' command performance) you're King Edward VII and you're sitting in the throne at the coronation durbar in India and afterwards you go round the corner for a beer and, even though they know you're the king-emperor, they still treat you like dirt. Bert Williams and Eddie Cantor were staying at a swank hotel together and returning after dinner one evening they were obliged to part company at the entrance: Williams had been allowed to check in to the hotel but only on condition that he use the service entrance and the service elevator.

"It wouldn't be so bad, Eddie," he said, "if I didn't still hear the applause ringing in my ears."

That was Bert Williams: a somebody and a nobody all at the same time.

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

If you're a Steyn Clubber and you feel that musicologically Mark is a total nobody, give it your best in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page. For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.