When filming wrapped on All That Jazz in March of 1979, director and choreographer Bob Fosse had just over eight years and six months left to live, although he'd thoroughly and pitilessly imagined his death in the movie he'd just finished filming. It would be more or less accurate: a heart attack, albeit on his way to the premiere of a revival of Sweet Charity in Washington, DC and not in a hospital bed while directing his latest Broadway show. With his imagined onscreen death still fresh in everyone's memory, it's doubtful that the end when it came was really a surprise to anyone who knew him.

It certainly couldn't have come as a surprise to Fosse.

There was little reason to imagine that Bob Fosse would become probably the most famous choreographer in the world, even when his career started taking off in the '50s, with work on shows and movies like The Pajama Game, Kiss Me Kate, My Sister Eileen, Damn Yankees, Bells are Ringing, New Girl in Town and Redhead. By the end of the '70s, however, he was probably the face of American dance, after the smash success of his second film (Cabaret), a television special (Liza with a Z) and Broadway shows like Pippin, Chicago and Dancin'. While there are doubtless other choreographers whose lives are interesting enough to deserve movie biographies (George Balanchine, Martha Graham, Jerome Robbins, Katherine Dunham) none of them took such an active hand in creating their own mythology while they were still alive.

If Fosse was worried about posterity – and there was never any doubt that he was – he did his job well. There are at least four biographies of Bob Fosse you can buy; his shows are regularly revived with particular care to preserve his choreography thanks to the efforts of a foundation set up by his widow, daughter and an ex-lover; and in 2019 FX aired Fosse/Verdon, an eight-part miniseries about his life and relationship with Gwen Verdon, his widow, starring Sam Rockwell as Fosse and Michelle Williams as Verdon.

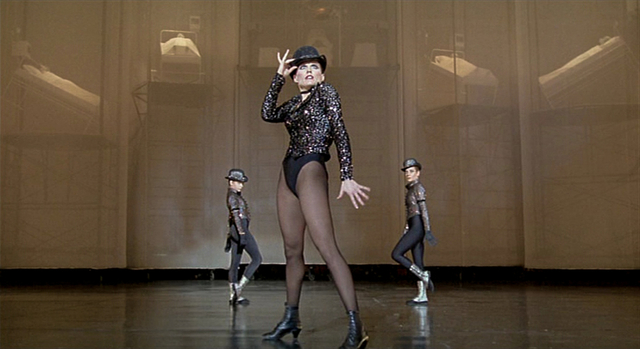

Basically, any time a dancer turns their feet in, does a tight little pelvic thrust, spreads their fingers wide and adjusts their hat, someone in the audience will turn to their neighbour and knowingly whisper "Fosse." He has left behind a signature set of physical gestures that are as iconic as those that embody our collective memory of Charlie Chaplin – or Adolf Hitler.

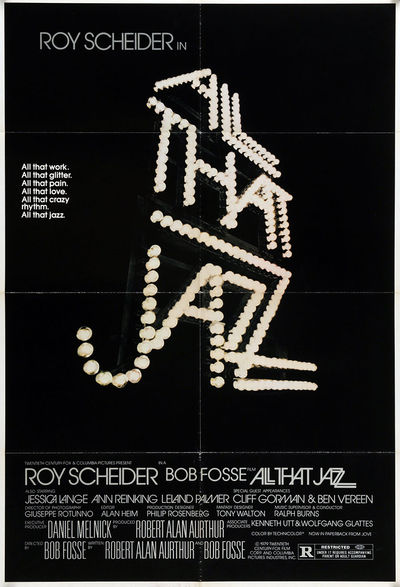

After a glitzy opening blast of music while the camera pans all over a marquee of the title rendered in white lights, the film begins on the stage of the Palace Theatre in New York City during an open "cattle call" for dancers, overseen by the show's director, Joe Gideon – a barely disguised version of Fosse, played by Roy Scheider.

Opened on Broadway between 46th and 47th Streets as a premiere vaudeville house in 1913, it became a cinema in the RKO chain in the early '30s. It alternated between shows and movie screenings for the next three decades, with runs of films like The Diary of Anne Frank sharing the stage with performances by Judy Garland, José Greco, Danny Kaye and Harry Belafonte. It was converted back to a Broadway venue in the mid-'60s, and was the theatre where Fosse and Verdon opened the Broadway run of Sweet Charity in 1966. The theatre was closed for a massive reconstruction in 2018; the last show to play on its stage was the musical version of Spongebob Squarepants. At the beginning of this year the theatre was being raised thirty feet into the air, as part of a renovation that will incorporate retail space and a luxury hotel. When it reopens, it's doubtful much of the space where Fosse filmed will remain.

Fosse was in the middle of a career low point when he made All That Jazz. Lenny, his follow-up to Cabaret, a biopic of comedian Lenny Bruce (though itself partially a portrait of the film's director), had opened five years earlier to decent box office but mixed reviews. He'd had a massive heart attack in 1975 while working on the production of Chicago. That same year the awards he had hoped Chicago would win were swept by A Chorus Line, whose director and choreographer Michael Bennett was being lavished with the praise Fosse thought he deserved.

Which is probably why the opening scene of All That Jazz plays out like a pointed echo of A Chorus Line – Fosse's attempt to evoke, reprise and surpass all of Bennett's show in just five minutes. In my humble opinion, he was wholly successful.

The whole scene is set to singer and guitarist George Benson's cover of The Drifters' "On Broadway", a 1963 collaboration between two songwriting teams – Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, songwriting legends at the Brill Building, located just two blocks north on Broadway from the Palace. The story of a desperate hopeful's longing for success on the Great White Way, it couldn't be more on the nose. Benson's slick but soulful version was released the year before on his Weekend in L.A. live album, and could probably be found on the turntables of nearly everyone Fosse knew.

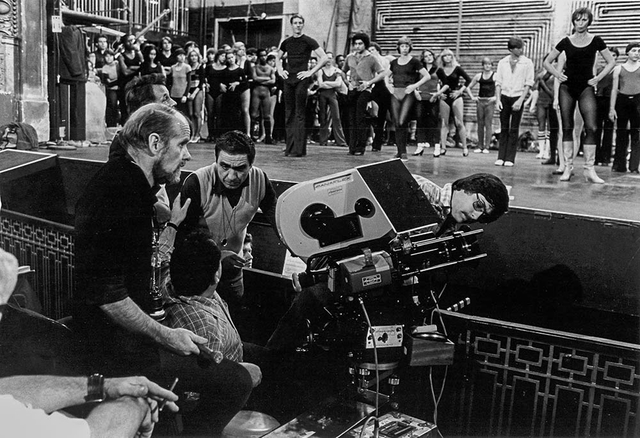

Fosse's camera takes an unblinking, documentary-like view of the hundreds of hopefuls who fill the stage at the Palace while Gideon and his assistant (played by Fosse's real life assistant choreographer Kathryn Doby) take them through the paces of "Tea for Two," a routine that Fosse created to test the training and capabilities of dancers vying for parts in his shows. Halfway down the orchestra section the show's producers and writers are nervously watching Gideon pare down the mass of dancers; at the back his ex-wife Audrey (Leland Palmer) and daughter Michelle (Erzsébet Földi) take it all in, making particular note of the most hopeless of the hopefuls.

There's almost no dialogue at all for the whole scene, but Fosse manages to pick out individuals in the mass of dancers in their spandex and leotards. There's a pair of twins – two petite, identical blonde women who make it through several eliminations, perhaps because their presence is both odd and endearing – and a comically inept young man whose ambition widely outpaces his actual talent; you get the feeling that there's at least one of him at every cattle call.

The talent, however, far outnumbers the dilettantes. Anxiety and nerves radiate off the screen as these dancers – many young, some not so young – focus intently on the steps being taught to the groups in front of them, desperate to master them in the few minutes they have to catch Gideon's attention in the throngs of bodies filling the stage from nearly its lip to the wall at the back, covered in an angular pattern of densely-spaced pipes whose purpose seems obscure. So many of them are stunning to watch, even if only for a second, cut into montages of gravity-defying leaps and pirouettes over Benson's music.

And they're relentlessly eliminated, sometimes quickly in clutches of dancers who seem relieved to escape the pressure of the cattle call, others individually, to heartbreaking effect, as Scheider approaches them one by one, looking them in the eye, shaking their hand as he sends them back to their lives to wait for the next cattle call. A tiny few are given lingering attention, like Victoria (Deborah Geffner), a stunning young woman with endless legs whose talent as a dancer is middling and singing voice even less notable, but whose looks obviously appeal to Scheider's Gideon for a mixture of artistic and carnal reasons.

The show, NY/LA, is being created as a showcase for Audrey, much as Chicago was made as a swansong Broadway outing for Gwen Verdon, and Gideon is juggling his work on it with the over-schedule, over-budget editing of Stand-Up, a film that's clearly supposed to be Lenny – and stars Cliff Gorman, the actor who'd played Lenny Bruce in the stage version of Lenny (but who had lost the role to Dustin Hoffman in Fosse's movie.) The editor of Gideon's film is played by Alan Heim, who was the real-life editor of Lenny, All That Jazz and Star 80, the 1983 film that would be Fosse's last.

Ann Reinking, the dancer who had recently ended a long affair with Fosse – among the closest in his life next to the one he had with Verdon – plays Katie, Joe's girlfriend, transparently based on herself. With what looks, then or now, like real cruelty, Fosse made her audition repeatedly to get the role.

All That Jazz is famous for a recurring set piece: Joe Gideon's morning routine. To a tape cassette recording of the "Concerto alla rustica" from Vivaldi's Concerto in G, Scheider performs his morning ablutions – a ministration of antacids, Visine and Dexedrine – before finishing up with a big grin for the mirror and Gideon's motto "It's showtime, folks!" We have no way of knowing if this was how Fosse began every day – the Dexedrine probably stood in for a whole cocktail of self-medication – but it underscores how Gideon is intently burning his candle at both ends. An occasional cough turns into a near-constant hack over the course of the film, and if you know how avidly the film reprises recent events in its director's life, we realize just what it means when Joe keeps massaging a chronic ache in his left arm.

Amazingly, Scheider was not the first choice to play Joe Gideon, though it's hard to imagine anyone else in the role today. Keith Carradine was originally cast by Paramount to play the protagonist in Fosse's next movie when it was called Ending. After the studio dropped the film, Fosse and screenwriter Robert Alan Aurthur began taking the story in a more blatantly autobiographical direction.

Robert De Niro and Warren Beatty were looked at to play Fosse's doppelganger, and the director even made a halfhearted attempt to pitch the role to Jack Nicholson but walked out, bored, halfway through watching a Lakers game as part of the actor's entourage.

When preproduction began on All That Jazz Richard Dreyfus had been cast as Joe Gideon, but he was never able to gel personally with Fosse – the actor described their relationship as "oil and water" – and after painful negotiations over breaking his contract, Fosse and his producers had to look for a new Gideon, eventually arriving on Dreyfus' Jaws co-star, Roy Scheider.

Dreyfus would have been a far less athletic Gideon, but he would also realized Fosse's worst picture of himself – resentful, angry, insecure and neurotic. Scheider was more physical, a cooler personality, more conventionally attractive, and it was probably imperative that Joe Gideon be made somehow more appealing to audiences if the film was going to succeed.

As he ceaselessly shows us, Fosse was a difficult, often unlikeable man: paranoid, maddening and demanding, a game player, a compulsive philanderer with the usual yin/yang combination of narcissism and self-loathing. In Fosse/Verdon we see him enjoy close relationships with male friends like Neil Simon and Paddy Chayefsky, but no one could deny – and certainly not the Fosse who made All That Jazz – that he was hell on the women in his life, holding them to a typical double standard when it came to faithfulness.

His taste in music paints Fosse as a product of the first half of the 20th century; living in the postwar world of dance and the movies provided a target-rich environment for this relentless cheat behind a smokescreen of domestic life, but the aftermath of the sexual revolution had put an unimaginable number of young women in his path, primed with a combination of sexual agency and ambition that a Bob Fosse is uniquely able to perceive and exploit.

Over and over during All That Jazz, Fosse's Gideon lets us know that he's never ignorant of what he's doing to them. As he's being wheeled into the operating theatre for heart surgery, Joe imagines that Audrey and Katie are on either side of the gurney; his last words are an apology to his wife for what he did to her, and to his lover for what he's going to do to her.

Fosse/Verdon, which counted Nicole Fosse among its executive producers, is all about filling out the emotional and artistic collaboration Fosse had with his third wife, the woman who never divorced him even after they separated. (Its title really should be "Fosse Was Really More Verdon Than You Knew.") It plays out like an extended bonus feature to All That Jazz, but puts most of its effort into redressing the short shrift Audrey/Gwen got in the film.

One of the most moving scenes in All That Jazz has Reinking's Katie and Földi's Michelle put on a performance for Gideon in his apartment – an exuberant dance set to Peter Allen's "Everything Old is New Again." As in real life, Bob/Joe's daughter Nicole/Michelle had a close relationship with Ann/Katie, and the two of them do their best to entertain him; the young girl is everything you'd imagine the daughter of two dancers to be, absorbing their influence and reflecting it back, eager for approval, but Reinking is captivating – agile and dynamic, a dancer at the height of her talent, practically exploding off the screen. For a moment, Scheider's Joe seems to relax, and his reaction to their gift to him is full of awe, tinged, perhaps, with a hint of contrition.

The film cuts occasionally to a fantasy sequence where Gideon goes through the detritus of his life in the company of Angelique, a stunning woman clothed in gauzy white, played by Jessica Lange. She embodies death, imagined by Gideon/Fosse as the most beautiful woman he'll ever see. That he will do anything – literally – to be with her has to be one of the most profound and elegant explanations of a death wish ever put on film. (Fosse had recently concluded an affair with Lange, pursuing her for over a year at the end of his relationship with Reinking; he was always certain that there was someone else holding her back with him, and sure enough there was: another dancer, no less than ballet superstar Mikhail Baryshnikov.)

The end, when it comes for Joe Gideon, is hardly brief: Fosse imagines his death in a long fantasy sequence – the "Hospital Hallucination" – with not one or two but five production numbers, all but the last of them featuring the women in his life letting Joe know how much his early death – one that he did almost nothing to prevent – will leave them bereft. (The song that gave the movie its title, a major number in Chicago, doesn't appear once in the soundtrack.)

The last song is the show stopper. In the movie, Ben Vereen plays O'Connor Flood, a schmaltzy, patently insincere caricature of the classic showbiz type hosting some kind of nonstop TV variety show – a reprise of the role Vereen had played in Pippin, more than faintly referencing Sammy Davis Jr. He steps out of the small screen to host Joe's last number – a no-holds-barred "wow 'em" number set to the Everly Brothers' "Bye, Bye Love," with Joe substituting the chorus with "Bye bye life...I think I'm going to die."

It's a tacky, tasteless crowd pleaser, wrapped in silver Mylar and full of the sort of crass show business excess that producers are sure audiences love, and which Joe Gideon might have normally labored to avoid. But "it's showtime, folks," and Joe is going to go out like a trouper, Scheider sliding across the stage on his hip, joining Flood for chorus after chorus, running into the audience to say goodbye to everybody before finding himself in a long hallway under the bleachers, moving inexorably toward Angelique, bathed in light. Then the beep of a cardiogram flatlines, and Joe is in a body bag, which is zipped up as the soundtrack fades in Ethel Merman singing "There's No Business Like Show Business." Fade to black.

While researching the screenplay for All That Jazz with Aurthur, Fosse made the bizarre decision to conduct a series of sometimes hostile, accusatory taped interviews, interrogating everyone he knew about their feelings about him. In All His Jazz: The Life and Death of Bob Fosse, Martin Gottfried recalled how the playwright Herb Gardner was startlingly blunt with his friend:

"You list your crimes at the slightest provocation," was Herb's opening line in Bob Aurthur's transcription of the tape. "I think you do it to absolve yourself. You go on record with your sins. It's the final play, the biggest con of all."

You have to wonder how Fosse felt during those final years of his life. There was the disappointing reception to Star 80, a film so bleak that it makes All That Jazz feel sprightly. There would be one more show, Big Deal, based on the 1958 Italian comic caper Big Deal on Madonna Street, but those last eight years would mostly be occupied with deals that went flat and revivals of old shows. He certainly did little to rein in the excesses that had killed him onscreen, and you have to wonder if imagining his death and saying goodbye made it easier to live out that last act feeling like he'd already made his apologies.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.