Steve McQueen has been gone for over forty years now but there's no sign that he's become either dated or irrelevant. A few years ago I stayed in a McQueen-themed hotel in Northern Ireland; the Bullitt in Belfast is a boutique hotel built around a courtyard where a mostly young clientele enjoys a party with DJs at night, and every room features murals of the actor. Even if many of those young people haven't watched The Cincinnati Kid or The Great Escape all the way through, it speaks volumes about the persistence of McQueen as a brand if nothing else.

The actor is known as the "king of cool," a nickname no amount of publicity can buy, and one that he earned honestly, the successor to John Wayne as a paragon of anti-hero masculinity in Hollywood movies. He's been written about endlessly, in multiple biographies, and his personal life – drinking, drugs, domestic violence, a brutal childhood – is as well-known as the car and motorcycle racing, and friendships with other masculine paragons such as Bruce Lee, James Garner and James Coburn.

At the start of the '70s he was at the peak of his box office appeal, which he tested by following up Bullitt with The Reivers, an adaptation of a William Faulkner story, and two racing films – Le Mans, his dream project, and a critical and box office flop, and On Any Sunday, a documentary about dirt bike racing that made a profit mostly because it cost nearly nothing to make. His next film teamed him up with another Hollywood rebel – director Sam Peckinpah – for Junior Bonner, a low-key drama about an aging rodeo rider.

Junior Bonner is called a western mostly because it's set in the American west and most of its cast ride horses or wear cowboy hats. Which would make it a western as much as, say, Yellowstone, the current "Sopranos in Montana" hit miniseries starring Kevin Costner. If the classic western is about the end of the frontier, Junior Bonner is about what happened decades after that frontier had been swallowed up by interstates, suburbs, malls, casinos and trailer parks.

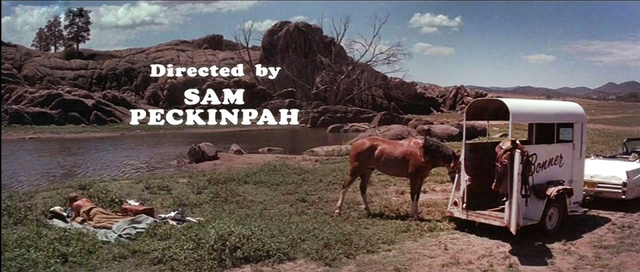

We meet McQueen's Bonner in Peckinpah's credit sequence – a series of frames within frames that follow him failing to ride a massive black steer, tending to his damage at the edge of the rodeo paddocks, then hitching his horse trailer to a mud-splattered white 1963 Cadillac convertible and heading down the road. It's a mostly wordless sequence, but thanks to a few clues – the mud on the car, Junior sleeping rough on a blanket by a stream – we know that McQueen's character is not riding high.

Junior pulls up to an old shack on a rough patch of land; it's his dad's place, but it's deserted, and the land nearby is being torn up by machines for a gravel pit. He's barely out of the old house when a pair of the machines move in and tear it down – the first of several trademark Peckinpah slow-motion sequences in the film. He ends up in a stand-off with a front-loader carrying a bucket load of rocks, gets forced to reverse up a hill and make a hasty retreat while the machines finish off the old homestead.

I won't insult your intelligence by laying out what it all means; some symbolism is clear enough for a child to read. As the film's trailer tells us, Junior has only one problem: "The twentieth century."

Junior pulls into a nearby town – Prescott, Arizona, his hometown, where he learns from his mother (Ida Lupino) that his dad, Ace (Robert Preston) is in the hospital after rolling his truck while drunk. His brother Curly (Joe Don Baker) had bought the old man's land for a bargain basement price so Ace could go prospecting for silver in Nevada. He's back, and broke, just in time for the town's annual rodeo celebration.

McQueen made Junior Bonner during divorce proceedings from his first wife, Neile, in the midst of what looked for all the world like a well-funded, high stakes midlife crisis. It doesn't show up onscreen, however; in McQueen: The Biography, writer Christopher Sandford described the film as a "walking hangover." Junior's only real goal in the film is to get back on Sunshine, that massive black bull in the opening credits, and hold on for the eight seconds that will win him much-needed prize money. Everything else that happens to him – mostly due to his dad and his brother - is happenstance.

The cast surrounding McQueen is fantastic. He was not an actor who let anyone steal a scene from him – the famous bits of business he used to draw your eye away from Yul Brynner and his other co-stars in The Magnificent Seven proved that it didn't matter how few lines you gave him, he'd still end up looking like the star.

Lupino and Preston as Junior's estranged parents are really the film's emotional centre. Ace is a hero, both in Prescott and on the rodeo circuit, and Preston utilizes the voice that audiences would remember from The Music Man to present a portrait of a man with a lot of stories, used to telling them over and over, even when everyone's heard them before. Lupino – one of film noir's greatest actresses and a director herself – completely fills out Elvira, weary and exasperated, the woman who's heard those stories one too many times.

They circle each other warily for most of the film until the end of the big barroom brawl scene at the film's centre; Ace tells her he's leaving for Australia and his last big scheme, and that they'll probably never see each other again. They acknowledge the significance of the moment and quietly make their way to a room in the hotel above the saloon – a last tryst that feels more romantic than the rather perfunctory one Junior ultimately manages with Barbara Leigh's Charmagne, his ostensible love interest in the film and McQueen's offscreen object of his affections during the shoot.

If the film has an antagonist beside Sunshine, it's Joe Don Baker's Curly – the white sheep of the Bonner family, a born salesman who's marketing the west to retirees in the form of "rancheros" in a retirement community, and a trailer park for those with a lower budget on their aspirations. He tries to enlist Junior as a salesman in his business – a local celebrity who could help sell that western dream. His virtue, Curly tells him, is his sincerity; he's as "genuine as a sunrise."

"I'm working on my first million," Curley tells his brother. "And you're working on eight seconds."

For his trouble, Curley gets punched through a window of their mother's home after dinner.

The other temptation set in front of Junior is a job working the burgeoning rodeo circuit for Buck Roan, who provides cattle, broncos and steers for riders. Roan is played by Ben Johnson, last seen in this column playing Melvin Purvis in John Milius' Dillinger (1973). Johnson, fresh off the Oscar he'd won for The Last Picture Show, was a former cowboy and rodeo rider himself, with dozens of roles in pictures like The Outlaw, Red River, Fort Apache, Shane and The Wild Bunch. Buck is fond of Junior – he's almost a backup father figure – and while you can see why Junior doesn't want a part in Curley's crass marketing schemes, you wish he'd take up Buck on his offer instead of pushing on to that next rodeo in Salinas.

The best scene in the film is easy to overlook; after tracking down Ace, who's checked himself out of the hospital and stolen Junior's horse to ride in the Prescott Frontier Days parade ("Hello cowboy" are the first words from father to son), the two of them take a chaotic ride through town and end up in the railway station, which appears to be abandoned – no longer even a whistle stop, the tracks used only by freight passing through.

They share a bottle and Ace tries to sell Junior on his latest big plan – silver prospecting in Australia, with sheep farming as a sideline. If he can't join him he can be the first investor, but Junior tells Ace that he's "busted." It takes the old man a moment to realize what he means, and another moment before it sinks in that he's probably the reason they're both in such sad shape so late in life. It's a lonely, forlorn moment that defines the two men, father and son, as holdovers and relics.

"The guy's kind of a dinosaur, just like me," Sandford quotes McQueen saying during a taped script conference for the film.

The derelict train station looked familiar, and then I remembered another hotel I'd stayed in a few years ago. The Murray Hotel in Livingston, Montana is an old railway hotel across from a fenced-off station where the trains don't stop any more. Rooms come with complimentary ear plugs in case you can't sleep through the freight trains that speed through the station at night, horns blaring. Peckinpah lived at the Murray from 1979 to 1984, and you can still stay in the suite named after him. The man was obviously drawn to places like this moribund train station.

Peckinpah worked from a script by Jeb Rosebrook, who attended Prescott's Frontier Days Rodeo as a teenager, and he lavishes a lot of care on setting the scene and the details of life on the rodeo circuit, and in towns like Prescott. When the camera isn't on McQueen, Preston or Lupino, the film feels like a documentary, lovingly capturing the faces in the crowds, and the rituals of rodeo riders before and after their turn in the chutes.

Everything converges in the bar at the Palace Hotel between the parade and the main events at the rodeo later in the evening. Ace and Elvira get to say goodbye, Curley gets to take a swing back at Junior, and Junior gets to hook up with Charmagne, while the whole bar explodes into a brawl that has the feel of a cherished annual event – a way for everyone to blow off steam, while the profits from the day pay for new stools, chairs and tables. Peckinpah shoots it with more than a hint of comedy, and it all ends when the band plays the national anthem.

It's best to watch Junior Bonner without expecting much; ABC Pictures made the mistake of marketing it as an action film, which it decidedly isn't, and despite good reviews from Vincent Canby of the New York Times and William Pechter in Commentary, it took years to make back its budget. McQueen loved the film, and today it's considered a neglected gem in his filmography.

"I made a film where nobody got shot and nobody went to see it," Peckinpah said.

McQueen and Peckinpah had an obvious affinity for each other. They were supposed to work together on The Cincinnati Kid before the director was fired and Norman Jewison took his place. Right after Junior Bonner the two began work on The Getaway, a story based on Jim Thompson's crime thriller, and the film where McQueen would steal co-star Ali McGraw from her husband, producer Robert Evans.

Peckinpah's career after Junior Bonner is erratic, even unpredictable. After arty, revisionist westerns like Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, he tried to make a blockbuster, which led to The Killer Elite, Cross of Iron and – it's still hard to believe today – Convoy, a film based on a novelty song about CB radios. A friend and huge Peckinpah fan told me it's important to understand that Peckinpah simply couldn't work within the Hollywood system, even when he wanted to. He delivered his last film, The Osterman Weekend, to the producers on budget and on time, but the producers took it back to the editing room and made a confusing story even more baffling.

Sam Peckinpah died of heart failure at the end of 1984; McQueen had died four years earlier, also of a heart attack, in a hospital in Juarez, Mexico.

Prescott's Frontier Days Rodeo is still happening, billed as the "World's Oldest Rodeo." The bar in the Palace Hotel is still there, a tourist hot spot, restored and renovated; there's a big Junior Bonner poster on the wall. They pulled up the tracks behind the train station in 1986 and built a shopping mall.

Junior ends up getting his eight seconds on Sunshine. He leaves Charmagne at the airport and drives past Ace as he rides out of town, but before he does he buys a first class ticket to Australia for his dad and has it sent to the Palace. The last scene shows McQueen's Junior towing his horse trailer behind his muddy Cadillac, heading to the rodeo in Salinas. And no matter how you feel about the weathered sincerity of a man like Junior, you can't help but hope that he'll take that job with Buck. There's only so much sadness you can handle, even in a movie.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.