In the middle of the most famous scene in George Stevens' 1943 romantic comedy The More the Merrier, Jean Arthur is half-heartedly trying to fend off Joel McCrea's wandering hands while she talks about her fiancé and the house they want to buy "when the emergency is over." It's strange to hear someone talk about World War Two – probably one of the most significant events in modern history – as an "emergency."

It makes the setting of the film, more adequately recalled as a catastrophe, sound like something that could be solved by invoking some municipal bylaw, or calling in the National Guard. Hearing it while watching the film in the middle of winter 2022, it weirdly echoed the language being used to describe the trucker convoys that have converged on Ottawa and other cities. It made me think that someone, somewhere, had chosen the wrong word.

The More the Merrier is a light screwball set during a catastrophe; that's probably the strangest thing about it, and it says something about Hollywood and America that this was even possible. It's hard to imagine the Germans or the Japanese (okay, maybe the Italians) greenlighting their propaganda cinema industry to make a comedy where one of the main characters is days from being deployed to the front, knowing that he might not return.

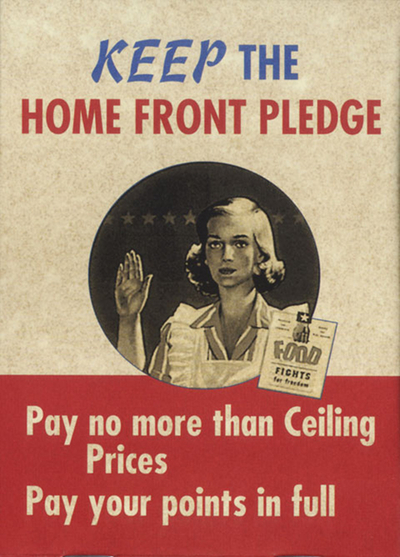

The film was made in 1942 and released in 1943, in the middle of the massive transformation of America's society and economy that took place after Pearl Harbor. What had once been mere villages or empty spots on the map were transformed into massive factory towns devoted to aircraft manufacture or shipbuilding, and overseeing it all was Washington – the home of Roosevelt's third term administration, whose enthusiasm for centralized power and regulation had been given free reign by the demands of a war economy.

The film begins with a cinematic cliché – a jovial travelogue straight out of a newsreel, describing the charms of Washington DC in a voiceover while the camera undercuts it. The city is packed to the gills, full of servicemen, newly-minted bureaucrats, dollar-a-year men (rich businessmen enlisted to run agencies, working for nominal wages) and an army of clerical staff and secretaries – young women, mostly, eight for every man as we're told repeatedly.

We meet Benjamin Dingle, played by veteran character actor Charles Coburn, a wealthy retired businessman in Washington to advise on the housing crisis, only to end up a victim of it. He arrives two days early to find his hotel room unavailable, and heads out to find a place to live. The only vacancy in the classified section has a lineup outside, but Dingle is a resourceful old millionaire, who disperses the crowd by jumping the queue, pretending to be the owner of the flat, then waits for the real owner – Connie (Jean Arthur), one of those thousands of women employed in war work. Using a combination of bluster and gentle bullying, he convinces her to rent him a room for a week, arguing that he's a better risk since any woman she'd rent to would only borrow her clothes and ruin them.

Connie is a stickler for efficiency, and works out a morning schedule timed to the minute that will allow the two of them to bathe, dress and eat before she has to join a carpool of other young women heading to work. What follows is the first slapstick sequence of the film, where the old man constantly sabotages her schedule by losing his pants, getting locked out of the flat, and bringing the coffee pot into the shower. Stevens – a director remembered mostly for helming serious, even epic films like Shane, Giant and A Place in the Sun – started his career at Hal Roach Studios, and had a key role along with Leo McCarey in creating the partnership of Laurel and Hardy, so his handling of the slapstick is reliable.

Leaving the apartment Dingle sees a young man walking down the street, holding yesterday's classified section. Joe (McCrea) is low key and distracted in demeanor (the actor was exhausted, having made three films in the same year, and had to be persuaded by Arthur and Stevens to sign on for a fourth); he's involved in some sort of war work, indicated by the massive aircraft propeller he's carrying. Dingle, who thinks Connie needs a "high type, clean-cut, nice young fellow", spontaneously judges that Joe fits the bill and offers to rent him half of his room and a Murphy bed.

This leads to another slapstick sequence where Dingle tries to hide Joe's presence from Connie in the tiny little apartment. It works for a few minutes, but they eventually pass each other in the hallway, and the outraged Connie, her face covered in cold cream, tries to evict her two new roommates until she's forced to admit that she's already spent the rent money Dingle paid her on a new hat.

The movie began as a vehicle for Arthur; she had bought the rights to Garson Kanin's short story "Two's A Crowd" hoping to use it as the last picture in her contract with Columbia Pictures, which she was desperate to be free from, having grown to detest studio head Harry Cohn and the demands of being a contract player. She brought Stevens along to direct, having enjoyed working with him a year previous on The Talk of the Town, and the two of them set about enlisting McCrea, who Arthur had first starred with in The Silver Horde in 1930 and again in Adventure in Manhattan (1936). While her husband Frank Ross worked on the screenplay with Kanin, they got Coburn signed on – Arthur had worked with him on The Devil and Miss Jones in 1941. With a sympathetic team built around her, the nervous and insecure Arthur hoped to ride out her last film for Columbia with relative ease.

Most of the movie takes place in Connie's cozy and chintz-filled, but tiny, apartment, but whenever the story leaves the flat Stevens does his best to convey the overcrowded city and the strangeness of life during wartime. It's a world turned upside down, where nearly any young man walking alone will be wolf-whistled by throngs of hot-eyed young women. When Joe and Dingle go out to a nightclub, they run into Connie, and his presence attracts her co-workers, also packed into the club; she's called to the phone, and looks back to see Joe surrounded at their table by the girls – outnumbered precisely eight to one. Walking home to the apartment later that night, they find the streets are full of servicemen and their girls, making out in the shadows beneath stairwells and trees – a spectacle that only enhances the sexual charge of that scene.

Earlier in the film the rooftops of the apartment buildings are shown as a hive of activity in the summer heat, full of sunbathers, al fresco diners and kids playing. There's a running gag where the lobby of Connie's building is shown empty, then over the course of a few days becomes filled with sleeping men, at first a few on cots then at least a dozen on bunk beds. It's a housing and homelessness crisis, albeit one where everyone involved is gainfully employed.

Thanks to Kanin, Ross and their co-writers, the film creates a knowing, mildly satirical portrait of the wartime bureaucratic state, embodied in Connie's fiancé Charles J. Pendergast (Richard Gaines), a rising star in the agency overseeing housing construction, who Dingle immediately recognizes when a man at a business luncheon fussily cites regulations that prevent the speedy construction of homes for war workers.

Pendergast is a drone, number cruncher and brown noser who brags about being invited to dinner at the White House ("The worst food in Washington," Dingle scoffs) and the old man immediately knows how to manipulate him, having encountered dozens, if not hundreds of Pendergasts over the course of his career. He's an overdressed figure of fun with a bad toupee, and Dingle makes it his mission to sabotage his engagement to Connie, even if it means reading Connie's diary, lying to the FBI and ruining her reputation.

(Pendergast's name-dropping is even noted when he's not around. During that famous seduction scene, Connie tries to celebrate her fiancé's career prospects to the otherwise occupied Joe, mentioning that he'd been to lunch with "Leon Henderson and Donald M. Nelson." Henderson was a Roosevelt advisor who was the head of the wartime Office of Price Administration, an agency so unpopular with rural voters that FDR had to replace him after his party's losses in the 1942 midterms. Nelson was a Sears Roebuck vice president who became director of the Office of Production Management and chairman of the War Production Board. Even if few moviegoers in 1943 would have recognized the names, you have to admire the writers for bothering to insert nuggets like this into their script.)

In any other movie Dingle's behavior would seem reprehensible, but in screwball world he gets a pass. Stevens wasn't the typical director of screwball comedy, despite his work on films like Vivacious Lady, Woman of the Year and The Talk of the Town – he favoured measured, deliberate pacing, with no sense of the chaos that usually bubbles under the surface of screwballs made by peers like Leo McCarey or Wesley Ruggles. (He was a painfully methodical director – "I rehearse on film," he once said, shooting miles of footage and assembling his performances later from multiple takes.) What he does, however, is happily portray the goofy quirks of his characters.

Dingle is full of bluster, and you suspect he enjoys it as a way of putting younger people ill at ease – he's particularly obsessed with Civil War hero and Union admiral David Farragut, and uses any opportunity he can to sing or bellow his motto "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" Joe is fond of barking like a seal in the shower, and the rooftop scene shows the two men dramatically reading aloud from a Dick Tracy comic, to Connie's disgust and dismay. There's a running gag about the rhumba in the film, and at one point the trio inhabiting the tiny apartment are shown separately dancing to a rhumba record on Connie's Gramophone.

In Romantic Comedies in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges, James Harvey underlines this tendency in Stevens films, noting the scene in The Talk of the Town where Arthur examines herself in a mirror, making a moustache out of her hair, and then impersonating Katharine Hepburn: "Lovely, lovely – rahlly lovely."

"The moment is wonderful just because it's so dumb," Harvey writes, "just the sort of thing people do when they're absolutely alone. Or think they are, of course..."

Arthur's nearly crippling anxieties as a movie star were out in full force during the making of The More the Merrier. She was a Hollywood veteran whose career stretched back to silents, 42 years old when she made the film; McCrea was 37, but both of them were apparently playing characters in their twenties. Arthur was so insecure that she locked herself in her dressing room, afraid that she looked "old and wrinkled" next to the chorus line of girls in the floor show during the nightclub scene. McCrea and Stevens had to work out a routine where they'd pretend to flirt with her to bolster Arthur's waning self-confidence.

Perhaps this is why the costumes for the film are more tightly cut and revealing than in nearly any other picture Arthur did in the last half of her career. Her hair is often done up pin-up style, her legs are on show, and her last outfit for the film is a revealing black nightgown with lace panels. Most flattering of all is the strapless black gown she wears in that famous scene, where Joe walks Connie back to their apartment from the nightclub.

She begins by quizzing him on the women he'd been involved with back in California, as they navigate between the canoodling couples all over the nighttime street. When they finally get to the stoop, she accuses him of not wanting to get serious.

"I just don't want to get involved," he says.

"They say that's what happens to a man when he gets married."

What Joe is serious about is pressing his part in their mutual attraction, which has simmered along throughout the film until this nearly delirious scene. His hands end up on her while she takes on and off her fur cape; sitting on the stairs, he lets them wander all over her while she tries to celebrate the stolid virtues of Pendergast, but the chemistry between them – you have to wonder what Arthur knew when she pressed for McCrea over Gary Cooper or Cary Grant – overwhelms them both.

The final act is a cascade of plot. After admitting that they love each other through the thin wall between their rooms, the FBI suddenly busts into the apartment looking for a Japanese spy – the result of Joe trying to get rid of a nosy and irritating neighbour kid. They're taken into custody, but when they ask that Dingle be summoned to vouch for them, he brings along Pendergast, who's scandalized by learning about the cohabitation, while Dingle says that he's never met either of them before.

His ruse neatly busts up the engagement when Pendergast is more worried about his reputation than Connie's – the only thing to do, Dingle tells them, is for Joe and Connie to get married as soon as possible to save Connie's name, and he helpfully offers to fly them to North Carolina where there's no waiting period on a marriage license, important since Joe is shipping out for North Africa in a day. The ad hoc nuptials are far from Connie's fantasy wedding, and she starts crying inconsolably while waiting for the plane home – and the annulment that Joe promises. Back at the apartment, however, he says that he's signing his soldier's pay and insurance over to her, and that he doesn't want his wife taking in any more boarders after what happened the last time.

This reduces Connie to hysterical bawling while the two of them get ready for bed, neither of them noticing that the wall separating their rooms has been removed – apparently the work of Dingle, who's hiding amongst the men sleeping in the apartment lobby. Her anguished tears turn to theatrically fake ones when they realize they're standing in the same bedroom now, and Joe takes this as his cue to comfort his wife. Outside in the hallway Dingle and several of his bunkmates begin a hearty chorus of "Full speed ahead – damn the torpedoes!"

And if that isn't one of the cleverest – and most shameless – ways of getting around the Production Code, I don't know what is.

Jean Arthur did finish her contract with Columbia and The More the Merrier was a hit, nominated for five Oscars for best actress, supporting actor, film, director and writing. (Coburn won for supporting actor.) She'd end up working with Stevens again, playing the mother in Shane – one of her rare movie roles after leaving Columbia.

Right after filming finished on The More the Merrier, Stevens enlisted, and led a motion picture unit that followed the US Army through D-Day to the liberation of Paris and through the camps at Dachau. His family and friends said that the war changed him, and he never made another comedy again.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.