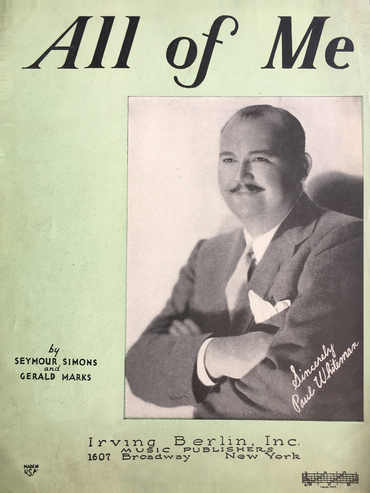

Nine decades ago - February 1932 - this was the Number One song and the Number One record in America. Paul Whiteman and his band doing their thing with a marvelous vocal by Mildred Bailey:

The composer of that Number One hit, Gerald Marks, lived 96 years and change, and toward the end of that long life I had the pleasure of hearing him explain to me how all hit songs are happy accidents. He attributed the success of "All Of Me" to two such accidents, one of which was less of an accident than a personal tragedy, as we'll hear. There is an element of truth to his theory, but it's not the whole story: The accident is being in the right place at the right time, but you need the right song to capitalize on it.

Marks was born in 1900 in Saginaw, Michigan, which is a long way from Tin Pan Alley. In the summer of 1931, he was playing in a band at a summer resort in Harbor Springs, which is a couple of hundred miles north-west of Saginaw on Lake Michigan. Between sets, Marks used to sit at the piano "noodling", and one night one of his noodles struck him as pretty good. So he worked on it a little bit, and the following day a little more, and the melody started falling into place. And a few nights later the whole thing came together, and, in between sets at his summer job, Marks found himself playing his first fully-formed tune.

This is the way he told it to me six decades later. As he's playing it through from A to Z for the very first time, a fellow starts strolling across the empty dance floor and stops by the piano. And, when young Gerald Marks has finished up the tune, the other chap introduces himself: "My name is Seymour Simons."

Seymour who man? Well, he was an older guy and he'd had a big song in 1926 with "Breezin' Along With The Breeze":

A few lesser lyrics along the way had done pretty well for Seymour, too - "Just Like A Gypsy", with the once great stage star Nora Bayes; "Hello, Baby" for Ruth Etting...

Gerald Marks didn't know any of that when Mr Simons came sauntering across the dance floor in Harbor Springs. "What's that tune you're playing?" he asked. Marks said it was just a little something he'd come up with, and Simons asked him to play it again. And again. And, after a couple more times, he said, "Would you mind if I put a lyric to it?"

"Sure. Why not?" said Marks.

As I say, that's the way Gerald Marks told it to me. If he'd played his tune five minutes earlier or five minutes later, it might have remained just that: a little finger-loosening warm-up he noodled around on in band breaks. But he chanced to play it at exactly the moment when a minor professional lyricist was crossing the floor, and so he wound up with a song.

Simons went upstairs to his room and came down about an hour later. Marks had built his composition on a three-note phrase that occurs throughout, so Simons offered him various suggestions for it. One of them caught Marks' fancy:

All Of Me

So Simons wrote it up. Oddly enough, after coming up with the killer title phrase, they use it twice in the first three bars...

All Of Me

Why not take All Of Me?

...and then steer clear of it until the very end of the song:

You took the part

That once was my heart

So why not take All Of Me?

Maybe they had the right idea. That three-note hook and its variations is mighty catchy but could have got a little boring with "All of me" pasted to it for 32 bars. Instead, they followed Ira Gershwin's advice:

A title

Is vital

Once you've it

Prove it.

Marks and Simons proved their title:. C'mon, take All Of Me:

Take my lips

I want to lose them

Take my arms

I'll never use them...

Having finished the song, the guys then prevailed upon the band's canary, Doris Robbins, to sing it the following night. If Marks' luck had held, a big Tin Pan Alley publisher would have walked in during the intro, and demanded to know what the song was and where he could find the guys who wrote it. Instead, Miss Robbins stood there and sang it, and it went ...okay, but nothing special.

Marks and Simons thought about what they should do with the song. The big publishers were in New York, not Michigan. So Gerald Marks scraped together some cash and figured he had enough to head off to the big town for a week. "I peddled my song," he said, "up and down the street, and every single publisher turned it down."

What didn't they like about it? Well, Marks told me they thought that, coming after an invitation to take one's lips and one's arms, the following line was "obscene" and "dirty":

Why not take All Of Me?

So at the end of the week Gerald Marks was broke and had no choice but to take all of him back on the bus to Michigan - where Belle Baker had been booked to play the Fisher Theatre in Detroit.

Belle who? Well, she'd been a headliner since she was seventeen. She'd come out of New York's Yiddish theatre and had hits like "Cohen Owes Me Ninety-Seven Dollars" (an early Irving Berlin song). More recently, she'd played the title role on Broadway in Betsy (1926), where she'd introduced "Blue Skies". She had a low, rich and resonant voice that Gerald Marks thought would be just right for "All of Me". So he and Simons inveigled their way backstage and were shown into her dressing room. And here is where Marks' "happy accidents" come into play.

The first accident was that there was a piano in her dressing room - and it was in tune! Even if you've been furnished with one, they usually aren't. But this meant the writers were able to perform the song for Miss Baker as opposed to just leaving her a piece of sheet music.

The second accident was, as I said above, kind of tragic. The guys got to the middle of the number:

Your goodbye

Left me with eyes that cry

How can I

Go on, dear, without you?

At which point Belle Baker broke down sobbing. The boys were mystified: What's up with that? Eventually, Miss Baker recovered sufficiently to wail, "That's my song!" She promised to put it in the act immediately, and that first time in Detroit it got seven encores.

A few days later she was back in New York and sang "All of Me" on a Saturday-night radio show. On Monday morning the music stores were flooded with calls about the song. And Gerald Marks and Seymour Simons had a hit. Not long after, Marks found himself lunching with Belle Baker and finally plucked up the courage to ask why she'd wept over the song in her dressing room that day. "Oh, I thought you knew," she said. "The night you and Seymour did the song for me in Detroit was exactly six months since my husband died."

Who was Belle Baker's husband? Well, he was Maurice Abrahams.

Maurice whobrahams? Well, Maurice Abrahams was a Russian-born songwriter. Not many of his songs are known today, although "Ragtime Cowboy Joe" was a hit for the Chipmunks in the Fifties, and their only British Top 40 success until their cover of "Achy Breaky Heart" in the Nineties. Mr Abrahams had some modest success with an early vehicular novelty called "He'd Have To Get Under, Get Out And Get Under (To Fix Up His Automobile)" and, in Belle Baker's only real starring movie role (Song Of Love, 1929), he provided her with "I'm Walking With The Moonbeams (Talking To The Stars)":

On April 13th 1931, a few weeks before Gerald Marks got his summer job in Harbor Springs, Maurice Abrahams had died: He was walking with the moonbeams and talking to the stars on a more permanent basi. And in her grief Miss Baker heard her own story in:

How can I

Go on, dear, without you?

You took the part

That once was my heart...

And that's when she cried, "That's my song!" And that's why she sang it. And who knows, if she hadn't been a widow in mourning, whether she or anybody else would ever have planted "All of Me" in the public consciousness.

By the way, Maurice Abrahams left his widow with a fatherless ten-year-old boy to raise. We'll come back to that lad in a moment.

Belle Baker never recorded "All of Me", but, if you listen very carefully, you can hear her singing it off-screen in the 1944 film Atlantic City:

Notwithstanding the lack of a commercial recording, discerning singers figured out pretty quickly that Belle Baker had something with "All of Me". Mildred Bailey recorded it with the Paul Whiteman band on December 1st 1931, and Louis Armstrong followed a few weeks later, and both records made it to Number One. Ben Selvin's orchestra took a crack at it, and, while not quite in the Mildred/Satchmo league, it snuck into the Top 20:

And then the song went away. What was the problem? In his book The Jazz Standards, Ted Gioia notes the contradiction between the how-can-I-go-on? words and the jaunty tune. "I can't help hearing a mismatch between the lyrics, which describe romantic surrender, and the triumphal attitude of his delivery," writes Gioia. Maybe other singers heard that mismatch, too. On the other hand, if you set that lyric to the melody it would seem to demand, you'd have something awfully maudlin and self-pitying. Nevertheless, "All Of Me" disappeared for a decade or so - until Billie Holiday retrieved the song in 1941 with an interpretation that seems to be somewhat equivocal about the all-or-nothing love and sits perfectly poised between the downbeat lyric and the upbeat tune:

Sinatra was a great and attentive Billie Holiday fan, and he surely heard that record. And three years later, on a "V disc" for the troops, he recorded it for the first time, in an Axel Stordahl arrangement that doesn't give Frank enough of a point of view on the song. Another three years passed and he tried again, this time with George Siravo and a jazzy little combo, whose piano intro sounds like it's leading you to a darkened side-street to some dive where some dumped loser is singing out his troubles. The band's great, particularly Clyde Hurley's trumpet. And the second chorus is a kind of duet between Sinatra and Babe Russin, whose tenor sax seems to be egging Frank on to really let rip. And it dawns on you that it's the perfect Sinatra song: he was cocksure and swaggering, but also the first male singer to project, seriously, vulnerability and loneliness and heartache. Hence, "All Of Me": a song for the swaggeringly vulnerable, for cocksuredness as a defense against heartache:

The first chorus is smooth, but in the second he roughs up the song a little:

Can't you see

I'm just a mess without you?

He kept that lyrical amendment in the act for the next forty years. By contrast, the spoken outro with which he concludes the song, over that piano vamp from the intro, failed to survive across the decades, but I always enjoyed it:

You better get it while you can, baby. I'm leavin' town pretty soon now. Yeah, I'm gettin' outta here...

Yeah, sure. Whatever gets you through the night, pal.

He sang a modified Siravo arrangement, trimmed to a minute or so, in the 1952 film Meet Danny Wilson. He's become the song now, the Frankisms more familiar than the original words:

Get these arms...

And the swooning bobbysoxers indicate that, indeed, they'd be very happy to get 'em. But that season the only record on the number was Johnnie Ray's, which bubbled just under the Top Ten in 1952. Sinatra would not make his definitive statement on "All Of Me" until two years later, for the album Swing Easy, by which time we're leaving Belle Baker's widowly anguish a long way behind:

Get a piece of these arms

I'll never use them...

The way Sinatra re-accents the second half of the song - "Your goodbye left me with eyes that cry" - against the drums and the brass thrilled me the first time I heard it, and has never ceased to thrill over the years.

Seymour Simons never heard that record. He had died five years earlier, when "All of Me" was doing okay but wasn't a blockbuster. There would always have been great jazz interpretations of the song - including a famous arrangement by Frank's old comrade Count Basie - but Sinatra is the guy who made it a pop standard. He's the reason "All Of Me" wound up very tenderly warbled by Willie Nelson in the Seventies, and then a generation later by Michael Bublé. If I had to name a non-Sinatra live performance that has stayed with me, it would, somewhat improbably, be by the London playwright Neil Bartlett. At the Institute of Contemporary Arts' 40th anniversary bash in the Eighties, Mr Bartlett came out and sang "All of Me" a cappella and without a shirt and, being gay and frankly somewhat cadaverous, he imbued it, without changing a word, with a topical and eerie Aids subtext:

Take these lips

I want to lose them

Take these arms

I'll never use them...

Gerald Marks kept on songwriting, because that's what songwriters do. He gave Shirley Temple "That's What I Want for Christmas" and Al Jolson his last great slice of southern ham, "Is It True What They Say About Dixie?" And after that not much. "All ff Me" isn't all of Gerald Marks, but it's pretty close.

Did Belle Baker ever hear that Sinatra record? She could have. She died in 1957, a couple of years after she'd been the subject of "This Is Your Life". But her life seemed to belong to another age - Yiddish theatre, vaudeville, all a long time ago. As mentioned above, she had a son, ten years old when his father Maurice Abrahams died in 1931. The boy took his mother's surname: Herbert Baker. And he went on to a not undistinguished screenwriting career that included some of the early rock'n'roll films - The Girl Can't Help It plus two of Elvis' least worst movies Loving You and King Creole - and the 1980 Neil Diamond remake of The Jazz Singer.

But Herbert Baker also had strong Rat Pack connections, especially with Dean Martin: He wrote a lot of the Martin & Lewis pictures, and then in the Sixties much of Dino's Matt Helm spy oeuvre, not to mention the Dean Martin TV show. Oh, and he also wrote Frank Sinatra's ABC television series in the late Fifties, including the edition of March 7th 1958 on which Frank sang the song Herbert Baker's mother had introduced in the wake of his father's death:

You took the part

That once was my heart

So why not take All Of Me?

A couple of years after I met him, Gerald Marks was gone. In accordance with his wishes, he was cremated and his ashes placed in an urn inscribed "All of Me".

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

If you're a Steyn Clubber and you find it all too easy to get along without Mark's maunderings, feel free to take a piece of him in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page. For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.