There should be more films about John Dillinger. He was, for just over a year in the early years of the Great Depression, among the most famous men in America, and the public face of its "crime wave" to the rest of the world. For connoisseurs of American gangster history, it's richly ironic that Bonnie and Clyde – two pitiful small time crooks who preferred to rob small town grocery stores and funeral parlours – have become romantic, sexy, rebellious legends in the wake of Arthur Penn's 1967 movie, overshadowing Dillinger, an audacious bank robber whose fame and influence was much larger at the time, as were his takings.

In a commentary track recorded for the 2005 DVD reissue of Dillinger, a 1945 film starring Lawrence Tierney as the outlaw, scriptwriter Philip Yordan says that the major Hollywood studios had an informal agreement not to celebrate gangsters by name. Monogram, the "poverty row" studio that made Dillinger, had no such agreement, and studio head Frank King turned down Louis B. Mayer's demand that he burn the negative for the film when Mayer refused to offer any compensation. It's a great story, but nobody knows if it's true.

In 1957, actors playing Dillinger appeared in two films – Guns Don't Argue, a low budget docudrama about the early history of the FBI, and Baby Face Nelson, a Don Siegel picture starring Mickey Rooney as Dillinger's murderous sometime associate. In 1965 the Zimbalist Company produced Young Dillinger, another low budget film starring Nick Adams as Dillinger and Robert Conrad as Pretty Boy Floyd. In 1979 Conrad would get his turn to play Dillinger in The Lady in Red, a cheapie made by Roger Corman's New World Pictures, with a screenplay by the young John Sayles. It bombed, and Corman would re-release it a year later as Guns, Sin and Bathtub Gin with the same result.

Dillinger would finally get the big-budget treatment he deserved in 2009, seventy-five years after his death in a Chicago alleyway, with the release of Michael Mann's Public Enemies, starring Johnny Depp as Dillinger. Based on Bryan Burrough's bestselling history of the crime wave and rise of the FBI during Franklin Delano Roosevelt's first term as president, it's a slick, stylish film that has a lot more sympathy for Dillinger as anti-hero than any previous version.

Mann tried to make his film as authentic as possible, actually shooting in locations like the Crown Point, Indiana jail that was the site of Dillinger's famous jailbreak, the Little Bohemia Lodge in rural Wisconsin where Dillinger and his gang escaped an FBI shootout, and the Biograph Theatre in Chicago where the gangster was finally cornered and killed. Mann even managed to borrow a 1932 Studebaker that Dillinger used in a robbery for the film. That said, Mann's film is about as historically accurate as any other picture featuring Dillinger, which is to say not very much at all.

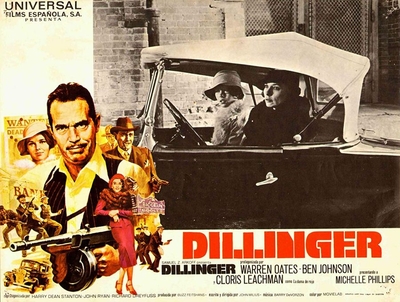

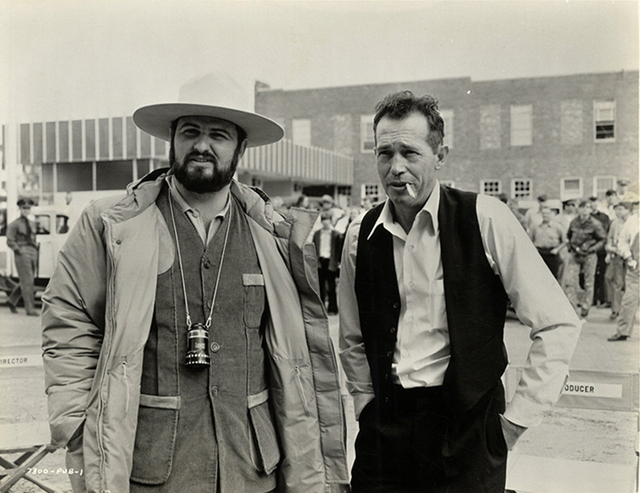

Amidst all this sporadic cinema history, probably the best film about the bank robber – America's second Public Enemy Number One after Al Capone, succeeded by Floyd, Nelson and then Alvin Karpis – is 1973's Dillinger, starring Warren Oates as the gunman, and directed by John Milius from his own script. Milius was a hot property based on his screenplay work on films like Jeremiah Johnson, Dirty Harry and The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean; he had also been contributing to the script of a film his friend Frances Ford Coppola was working on – one that would eventually get made as Apocalypse Now.

But he wanted to get behind the camera ("Being a director is the only way anyone will listen to you in Hollywood," he told the Wall Street Journal) and accepted an offer made by Samuel Z. Arkoff and his b-picture factory American International Pictures. Arkoff gave him a choice between two blaxploitation pictures (Blacula and Black Mama, White Mama) and a gangster picture he could write himself. Milius chose to make a picture about John Dillinger.

Johnny Depp's Dillinger isn't unlike most of the actor's performances – he inhabits the role like he's alone on the screen. Laurence Tierney's Dillinger in the 1945 film was nothing sort of a cold-eyed sociopath; "mean as a snake" as Milius describes him in the commentary track he shares with Yordan, the movie's scriptwriter. This wasn't apparently very far from the actor in real life; Tierney lost the title role in Joe (1970) to Peter Boyle when he assaulted a bartender two weeks before filming, and he was fired from Reservoir Dogs when he brawled with director Quentin Tarantino, who described the 72-year-old actor as "a complete lunatic."

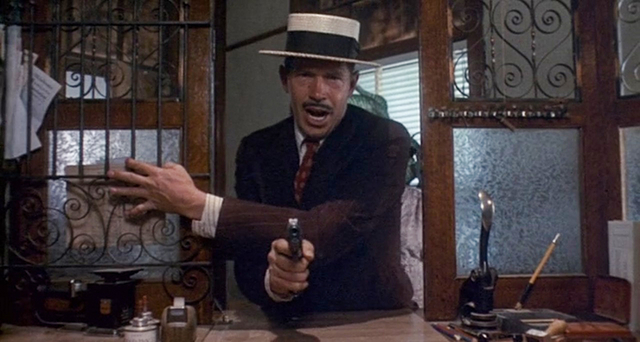

Warren Oates as Dillinger, however, might be among the most perfect bits of casting, if only for the actor's startling resemblance to the real gangster. We meet Oates' Dillinger in one of the many small town banks he robbed, from the point of view of a teller who ends up on the wrong end of Dillinger's pistol. He has flair and confidence – he acts like he was born for this sort of work, and in Milius' conception of him it's the core of his sense of self. The director would call him "the greatest criminal that ever lived," a hyperbolic and subjective opinion in retrospect, especially when you consider how much more money a white collar criminal like, say, Bernie Madoff could steal, compared to a hood like Dillinger.

Most of all, Oates' Dillinger has an unshakeable sense of his celebrity, and the notoriety his crime spree confers on his confederates and his victims. "You're being robbed by the John Dillinger gang, the best there is. These few dollars you lose here today are going to buy you stories to tell you children and great grandchildren," he tells the hapless depositors in that small town bank. "This could be one of the big moments in your life. Don't make it your last."

Dillinger's celebrity was undeniable, both during the apex of his crime spree and decades later; growing up in the late '60s and '70s, I can't remember a time when I didn't know who he was, what he looked like, and at least a few of the highlights of his short career. In Public Enemies, Bryan Burrough quotes a 1934 issue of Time magazine that illustrated Dillinger's exploits as a board game, and compared him to Tom Sawyer: "Sometimes he may have dreamed of being another Abe Lincoln or Jesse James... (but not) that he would achieve a great unwritten odyssey: Through the Midwest with a Machine Gun."

In big cities moviegoers would cheer when Dillinger's face appeared in newsreels, but his real popularity, like that of other celebrity gangsters at the time, was in rural areas hardest hit by the Depression, where foreclosing banks were considered more of an enemy than the crooks robbing them. Will Rogers wrote that "if the Democrats don't get Dillinger (they) may lose this fall's election."

Politicians knew they were competing with gangsters for popularity. In a radio speech, Roosevelt was pleading with voters to cooperate with the law to catch these outlaws: "Law enforcement and gangster extermination cannot be made completely effective while a substantial part of the public looks with tolerance upon known criminals, or applauds efforts to romanticize crime."

But Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde, Pretty Boy Floyd, Machine Gun Kelly and the other marquee names of the early '30s crime wave were also incredibly useful to FDR's push to centralize the power of federal government, and to J. Edgar Hoover's fledgling Bureau of Investigation, which would be rechristened as the Federal Bureau of Investigation the year after they tracked down and killed Dillinger. As long as they were on the loose, the headlines these bank robbers, stick-up men and kidnappers generated helped push anticrime measures into law, like ones that made it a crime to kill a federal agent, and authorized Hoover's agents to carry guns and make arrests.

In Milius' Dillinger, the gangster's nemesis is Melvin Purvis, head of the FBI's Midwest division, played by western actor and former rodeo champion Ben Johnson, just two years on from winning an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in The Last Picture Show. The real Purvis was a slight man with a squeaky voice, barely thirty years old during the height of the Dillinger gang's fame. Milius and the very middle-aged Johnson make Purvis an imposing but courtly badass, lighting a cigar every time he kills a gangster, walking alone into an isolated farmhouse wearing a bulletproof vest and holding two pistols to take down Wilbur "Mad Dog" Underhill, the "Tri-State Terror".

"Guts, sheer guts," as one of his men describes him. In real life Purvis was nowhere near the scene when Underhill was ambushed by the law, surviving the gun battle long enough to flee the scene barefoot and in his underwear, collapsing on a bed in a furniture store where he was captured before dying in the hospital.

In both Michael Mann's and Milius' films, Purvis is a chivalrous character. As played by Christian Bale in Public Enemies, he violently intervenes to prevent Dillinger's girlfriend Billie Frechette (Marion Cotillard) from being tortured during interrogation by rogue lawmen. In Milius' film, Johnson's Purvis gently picks up an injured Frechette (ex-Mama Michelle Phillips in her first role after the debacle of Dennis Hopper's The Last Movie) and carries her from the scene of the Little Bohemia shootout.

This generous treatment of Purvis has historical roots. The first is the actual, media-enabled hero worship that surrounded the man – despite the blunders committed – during his pursuit of the Dillinger gang. It was a notoriety that would poison his previously close relationship to Hoover, who resented how Purvis was collecting headlines that he thought were due to the agency – and himself.

The relationship would sour enough to force Purvis out of the FBI in 1935, after which he moved to Los Angeles to try and trade on his celebrity, served in the Army during World War Two, and then returned home to South Carolina to practice law. For the rest of his life he would find opportunities and appointments blocked by Hoover's FBI, who carried on a quiet vendetta against the former agent.

Milius was clearly as fascinated with Purvis as he was with Dillinger, and their conflict is the engine of his film. After the film did well at the box office, he worked on the script for Melvin Purvis: G-Man, a 1974 TV movie and sequel to Dillinger, starring onetime cowboy actor Dale Robertson as Purvis. This led to The Kansas City Massacre in 1975, another TV movie with Robertson as Purvis, though Milius declined to participate, hating the experience of writing for television.

Milius shot Dillinger entirely in Oklahoma, which in the early '70s looked remarkably unchanged since the Dustbowl days. In his commentary track to the 1945 Dillinger, Milius complains that Tierney and his gang look like classic film noir heavies – sharp-dressed and urban, holed up in big city hotels while on the lam. He preferred his take on the gangster who was, like most of his peers, rural and Midwestern, small town boys and farmer's sons, hicks and hayseeds who weren't content with a quiet life.

In this context Oates' Dillinger and his gang stand out from their surroundings. Hiding out in Tuscon, Arizona, they're conspicuous at a country dance with their new clothes and big cars, and the sheriff and his deputies spot them immediately. "Decent folk don't look that good," he says.

Most Dillinger stories climax with his end at the Biograph Theatre in Chicago, after a screening of Manhattan Melodrama. In Milius' film it's the shootout at Little Bohemia, where Purvis and a team of heavily-armed G-Men try to capture Dillinger and his gang, which in Milius' version of the story includes both Pretty Boy Floyd and Baby Face Nelson. (Floyd was never a member of the Dillinger gang, and it's doubtful Floyd and Nelson ever met.)

The real Little Bohemia ambush was really a debacle for Purvis. The gunfight broke out when his agents opened fire on three innocent men who were leaving the lodge, killing one of them. And despite the massive barrage of bullets fired by both lawmen and gangsters, Dillinger and his gang escaped, leaving behind one dead and five wounded agents.

Milius depicts Little Bohemia as nothing less than a battle out of a war film, with a huge body count as both sides open fire on each other with Thompson submachine guns, grenades and Browning Automatic Rifles. Dillinger is a bloody film, and this scene is its bloodiest, with one gang member who was wounded before the FBI arrived being shot – a mercy killing – by Floyd. (Who wasn't, that's right, even there.)

The aftermath is just as bloody, and Milius lets it play out as if it was all part of the same, long terrible day. Nelson – played by Richard Dreyfus as a belligerent psychopath happy to gun down innocent bystanders – is cut down in a field, still in his pajamas and housecoat. Gang member Homer Van Meter (Harry Dean Stanton), the film's comic relief, steals a college boy's car and coonskin coat, but ends up cornered in the middle of a small town main street by a posse of trigger-happy lawmen and locals looking for the gang.

"Goddamn it," he says. "Things ain't working out for me."

Floyd is cornered in a farmhouse where he's sitting down for lunch with a sympathetic old couple who pray for his soul, and gets gunned down in their field by Purvis and his men. With his dying words he tells Purvis he's grateful that he was the one that got him.

In real life, Baby Face Nelson died after Dillinger, in a gun battle just outside Chicago in November of 1934. Van Meter also outlived Dillinger, and was killed in St. Paul, Minnesota by a group of lawmen that included a corrupt cop whose campaign to become sheriff of the town – known as an outlaw refuge - had once been supported by Van Meter. Pretty Boy Floyd – who was, once again, never a member of the Dillinger gang – was killed by a group of agents led by Purvis, in a corn field near East Liverpool, Ohio, three months after Dillinger's death.

In Milius' film, Cloris Leachman plays Anna Sage, the "Lady in Red" – a brothel keeper who was being threatened with deportation back to her native Romania. Over popsicles, Purvis promises to help her out if she'll assist in the capture of Dillinger, who has been keeping company with one of her girls. Dillinger ends, as it should, in the alleyway next to the Biograph. In other films there's a crowd of agents and bystanders; Milius ends his film with Purvis confronting Dillinger alone, calling out his name to get him to draw, then gunning him down.

In real life Purvis was nowhere near Dillinger when three federal agents opened fire on the gunman, wounding two innocent female bystanders. After the credits roll Milius ends the film with a coda – a denunciation of the film written by J. Edgar Hoover just before he died in May of 1972, a year before the film's premiere. Recited by voice actor Paul Frees, Hoover insists from beyond the grave that "Dillinger was a rat that the country may consider itself fortunate to be rid of, and I don't sanction any Hollywood glamorization of these vermin. This type of romantic mendacity can only lead young people further astray than they are already, and I want no part of it."

Before the film is over there's a summary of the fates of each main character. Anna Sage was deported to Romania and Billie Frechette, we're told, moved back to her mother's house on an Indian reservation in Wisconsin where she died single and penniless. Sage did, in fact, die in Romania of liver failure in 1947, but Billie Frechette married twice and had children, dying in Shawano, Wisconsin in 1969. After her release from prison in 1936 she toured in a show called Crime Doesn't Pay with members of the Dillinger family, including his father. (One of these shows is the opening scene of the 1945 Dillinger.)

Melvin Purvis died of a gunshot wound in his South Carolina home in 1960, inflicted by the gun that he used to shoot Dillinger, according to the pre-credit sequence. The gun was actually a gift from his bureau colleagues upon leaving the FBI, but since Purvis didn't kill Dillinger, it's a moot point. His death is often described as a suicide, but other accounts claim it was an accidental discharge; Milius might have slyly referred to this in a scene where Johnson's Purvis conspicuously empties the chambers of his Colt before letting a boy hold it.

There's even a story out there that Purvis was assassinated after discovering something while serving on a commission investigating the judiciary. (Trust me, I'm not trying to spread a conspiracy theory, which in any case made it into no less than a 2017 PBS documentary about Purvis.)

History has not been kind to J. Edgar Hoover; the (reputedly) cross-dressing, closeted lifetime head of the FBI is considered in some quarters a villain far worse than Dillinger for expanding the powers of his agency beyond reasonable oversight, making law-abiding Americans the object of surveillance and investigation. The overreaching criminalization of speech and dissent might have its roots in the crime wave of the early '30s, which allowed the rise of a powerful unelected bureaucracy with unconstitutional powers.

John Milius is still around. His friend Francis Ford Coppola gave him a percentage of Apocalypse Now to thank him for his work on the script; in exchange Milius gave Coppola a percentage of Big Wednesday, his 1978 film about surfers. The picture bombed. Milius' career hit its peak in the '80s with Conan the Barbarian and Red Dawn, though he says he was ultimately blacklisted by Hollywood for his right wing views. He was a major player in the startup of the UFC mixed martial arts organization. He eventually got over his distaste for television, writing and producing the series Rome for HBO.

The Biograph Theatre is still there, as is Little Bohemia Lodge, where you can have drinks and dinner while looking at gangster memorabilia and original bullet holes. But they still haven't made a definitive movie about Dillinger, whose real story doesn't need embellishment or rearranging, and might be well served by a six-part miniseries on HBO, Apple+ or Netflix. Maybe that's something John Milius might be interested in trying; he must want us to forget about that remake of Red Dawn they made that replaced Russians with North Koreans.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.