William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody was probably the most famous American in the world for several years near the end of the nineteenth century, rivaled only by Mark Twain. He was still famous when I was a boy, but I'm not sure you can say that anymore; when researching this column, Google searches for "Buffalo Bill" were more likely to return Ted Levine's serial killer villain in Silence of the Lambs than the man whose Wild West Show was once the most popular entertainment spectacle on three continents, a precursor and model for the western movies that remained to be made.

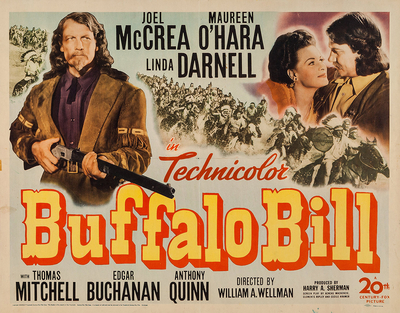

Narration at the start of William A. Wellman's 1944 biopic of Cody – simply called Buffalo Bill – notes that it's been 60 years since Cody and his exploits became famous, mostly thanks to dime novels, stage shows and the Wild West shows that Cody began touring in 1883, featuring frontier stars like Annie Oakley and Chief Sitting Bull. To put that into perspective, it's roughly the same number of years that separate us from the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, the end of Elvis Presley's army service, the premiere of West Side Story and the first Beatles lunchtime shows at Liverpool's Cavern Club. There were still plenty of people around – like Wellman – who were alive to remember the height of Cody's fame.

In my own family, a distant connection to Cody on my mother's side was a persistent ancestral myth, like the chauffeur who ran off with the lady of the house (a tall tale straight out of Downton Abbey.) Cody's abolitionist father was, in fact, born just outside of Toronto, though long before my people arrived here, and no genealogical link has ever been unearthed. But years of hearing the story has given me a strange stake in the Buffalo Bill story, and doubtless nudged my hand toward this movie.

Wellman's Buffalo Bill doesn't start promisingly. Indian warriors on horseback are chasing a wagon through an arid western landscape, their arrows missing the passengers, who have to shelter behind their wrecked carriage when it overturns. The film is shot in Technicolor, with big klieg lights filling in the shadows, as garish and overlit as most early colour studio films. Suddenly, gunshots ring out from the rocks behind the crashed wagon, each one finding their target as cleanly as the natives' arrows missed theirs. Less than five minutes in and there's little to distinguish Wellman's film from any other cornball oater or Saturday morning western serial.

The marksman who saves the luckless party is Buffalo Bill Cody (Joel McCrea), a scout and buffalo hunter employed by the nearby U.S. Army fort, and something of a legend in the area, if not in the country or the world – yet. Among the passengers who owe Bill their lives are a United States senator and his daughter Louisa (Maureen O'Hara). She rages against the Indians who tried to ambush them but Bill will have none of it – he's angrier at the corrupt agents who sell them alcohol, insisting that "Indians are good people – if you leave them alone."

Buffalo Bill is a strange film. On the surface it's as sentimental and mythologizing as you'd imagine – the sort of western that gives westerns a bad name, at least among people looking for a reason not to like westerns.

On the other hand it's almost militant about giving Native Americans the respect and dignity they're usually denied in our most uncharitable ideas about westerns – mostly because of McCrea's Cody, their constant champion in the film even if he's responsible for killing more of them onscreen than any other character.

Louisa, clearly interested in the frontiersman, invites him for dinner at the fort with her father, where he meets Vandervere, an eastern tycoon building a railway through the area, and Ned Buntline, a journalist played by Thomas Mitchell as a loquacious, comic blowhard. Buntline would be the key figure in Cody's legend, the man whose tales of the west publicized and hyped Cody's exploits, turning him into a living legend.

He was as colourful a character as Cody, perhaps moreso – a veteran of both the US Navy and Army, dishonorably discharged for drunkenness, a temperance lecturer, bigamist, fabulist and instigator of the 1849 Astor Place Riot. He wrote himself heavily into Cody's exploits and was rewarded when Colt named a .45 pistol after him – the long-barrelled Buntline Special that Wyatt Earp was reputed to carry. (This last fact is now considered about as accurate as anything Buntline wrote.)

Cody's reputation leads to requests to lead expeditions for eastern greenhorns and rich men to hunt Buffalo, and he ends up marrying Louisa, who gives birth to their son, Kit Carson Cody, in the wilderness hut of an old Cheyenne woman who acts as midwife. The buffalo hunts turn into a slaughter, which deprives the local tribes of their source of food and shelter. This causes a revolt, and an alliance among the Sioux and Cheyenne that peaks with the death of General Custer and his 7th Cavalry at Little Bighorn.

Cody is reluctantly pressed into service to lead the troops avenging Custer's death, and end up fighting heroically at the Battle of Warbonnet Creek, fighting one on one with a Cheyenne war chief named Yellow Hand – played by Anthony Quinn. Yellow Hand had been Cody's childhood friend, we're told, and the debt owed to Cody by the chief led to the resolution of an earlier conflict with the Cheyenne, who had kidnapped Louisa's father. There's no resolution this time, however, and Cody kills Yellow Hand.

The subsequent battle is clearly supposed to be the picture's highlight, drawing on Wellman's talent as an action director. It was so successful that it would be re-used later by Fox, in Pony Soldier (1952) and Siege at Red River (1954), cropped to fit the new widescreen format. Bill's heroism gets him awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (later revoked when the US government decided it would be a strictly military honor). Traveling to Washington for the ceremony, he learns that Buntline has made him a national celebrity.

Wellman and his scriptwriters do their best to underline the respect Cody holds for Yellow Hand and his people. They even insert a subplot involving Dawn Starlight, a Cheyenne woman teaching school at the fort's school, played by Linda Darnell (who at least had some Cherokee in her background). Darnell plays a variation on the "tragic mulatto" stereotype – an attractive woman trapped between two cultures, carrying an unrequited torch for Cody. She dies at Warbonnet Creek – mysteriously the only woman seen there – and Cody recovers her corpse, gently carrying it from the battlefield.

"A friend of yours, Bill?" a soldier asks.

"They were all friends of mine," Cody replies.

There was a Battle of Warbonnet Creek in the summer of 1876, Cody was there, and apparently did kill a Cheyenne warrior named Yellow Hair, not Yellow Hand. What the film omits was that Cody was already starring as himself in shows out East, performing during the winter and heading back west for the summer campaigns in the Indian Wars of General Philip Sheridan. He was grieving that year, as his son Kit had died of scarlet fever that winter in Rochester, NY, where three of Cody's children are buried. And after killing Yellow Hair, Cody took his knife, headdress, saddle – and scalp – as trophies and sent them back to be displayed in a friend's shop window in Rochester.

That, I suppose, is what friends are for.

You probably won't be surprised to learn that, while Cody did marry a woman named Louisa Frederici, her father wasn't a senator. Their estrangement is a crucial part of the plot of Wellman's film; Cody and Louisa did petition for divorce twice, in 1883 and 1905. She claimed he was unfaithful; he said she tried to poison him. He tried to preserve his reputation by making their separations a quiet affair, but the second time she fought back in court, leading to unwanted headlines. They ended up reconciling in 1910, and she remained with Cody until his death in 1917.

Wellman had apparently set out to make a very different movie – a debunking of the Buffalo Bill myth that downplayed his heroics and portrayed him as a showman above all, more P.T Barnum than Wild Bill Hickok – but decided against it at the last minute. That film would ultimately be made by Robert Altman as Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson. Released in 1976, it features Paul Newman as Cody, a wig-wearing circus master, drunk and fraud, and Burt Lancaster as Buntline, the mythmaker whose ongoing commentary undercuts the Cody legend.

In Buffalo Bill's Wild West: Celebrity, Memory and Popular History, Joy S. Kasson applauds Altman for capturing the spectacle of the Wild West show:

"The details of Buffalo Bill's costumes, the tunes played by the cowboy band, the cameo portrayals of figures like Ned Buntline, John Burke and Nate Salsbury all give the impression of a roomful of Wild West posters and programs come to life. The film has the look of a lovingly accurate tribute to Cody's show, but its content is critical and somber."

"The film is a bicentennial meditation on American heroism at the end of the trail," Casson writes, "irredeemably enmeshed in showbiz posturing. If the staginess of American national identity infuses Altman's film with energy and spirit, it also rules out any unambiguous affirmation of the traditional values Buffalo Bill and his promoters always claimed to promulgate. In the contemporary world, Altman seems to argue, America's self-understanding cannot be taken any more seriously than the popular entertainments that promulgate it."

It will come as no surprise that Robert Altman and Hollywood in the mid-70s were hell-bent on debunking the Buffalo Bill myth and the West in general, but why was Wellman originally intent on doing the same thing in 1944 (there's no answer, as details about this original script and its contents remain apocryphal) and what did he substitute for it?

The real conflict in Wellman's film doesn't begin until Cody journeys out east to collect his medal. While there he's called to his son's deathbed, where he learns that the boy has died of diphtheria (not scarlet fever) – a "disease of civilization" as the doctor describes it, of crowded cities, poor sewage and poisoned drinking water. The deathbed scene is played like Victorian melodrama, all deep shadows in rooms full of ornate furniture and swagged draperies.

But what follows wouldn't be out of place in a novel by Upton Sinclair, as Cody rebels against rich businessmen like Vandervere when they pay tribute to him, protesting that they're exploiting the west, its people and the Indians. He sees them as representatives of the civilization that poisons the land and killed his son, and Buntline warns him that they'll make him suffer for not playing along. (The real Cody was a Scottish Rite Freemason, so it's anyone's guess how much antipathy he actually had toward civilization.)

Vandervere, the money behind both the railway and the buffalo slaughter, is meant to stand in for the railway tycoons and robber barons – men like Jay Gould, John Jacob Astor and Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose name is echoed in Vandervere's own. William Wellman, 20th Century Fox and America might not have welcomed a debunking of Buffalo Bill in 1944, but they were obviously ripe for an attack on the moneyed interests and plutocrats profiting from the labour and speculation that powered Manifest Destiny.

Looked at this way, Buffalo Bill is evidence of the triumph of muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell, who died the year it was released.

On cue, old allies like the general back at the fort turn on him, and the media begin slandering Cody – in a montage sequence of newspaper headlines, he's shown punching the lights out of one editor. They still manage to ruin him, however, and he ends up trying to stake his Medal of Honor at a shooting gallery in a sideshow arcade to win a dollar. His marksmanship gives the proprietor an idea; he puts Buffalo Bill on display as an attraction, and the public's lingering fascination with the western hero brings both Louise and Buntline back into his life, the latter helping cook up the idea of a Wild West show.

That Wild West show – the bedrock of the Buffalo Bill myth, dubbed "America's National Entertainment" – is barely given any screen time by Wellman, who obviously preferred to put the effort into the Battle of Warbonnet Creek. Decades of shows and tours are compressed into the entrance of the performers – a montage of Indian warriors and Pony Express riders, chuck wagons and stagecoaches and U.S. Army cavalry – through the gate of some arena somewhere, with Cody being saluted by Queen Victoria, Teddy Roosevelt ("Bully!" the lookalike declaims to the camera) and some pasha in a distant land, who drapes McCrae's Cody with strings of jewels.

We see Cody age, his hair turning grey and then white, the elegy for the passing frontier implied, while it was acknowledged outright in newspaper reviews and in programs for the Wild West show, like the one from 1902 that Kasson quotes in her book:

"Soon the dark clouds of the future will descend upon the present, and behind them will disappear the Wild West with all its glories, forever made mere memories; and as it fades behind nature's impenetrable curtain will be hallowed by a timely and dignified – FINIS."

Wellman's film ends with the white-haired and wet-eyed McCrae at the final Wild West show, saluting his audience - both the kids in the gallery and the adults up front, who had once sat back there. The camera cuts to a boy with crutches – doubtless some American Tiny Tim – who cries out "And God bless you too, Buffalo Bill!"

Wellman recalled years later, for The Men Who Made the Movies, Richard Schickel's 1973 documentary series on Hollywood directors, that as soon as he called "Print!" on this shot and the camera stopped rolling, he turned on his heel and vomited.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.