Gene Austin died fifty years ago - January 24th 1972. If you don't know the name, well, his celebrity was much diminished by the time of his death, and has faded to all but undetectable levels in the decades since. But he's a big part of the answer to a question I get asked quite a lot. This department is generally in the business of songs rather than records - songs that endure over the decades and turn up in a thousand re-arrangements on zillions of records. It's different in our age, when new songs are generally conceived as a full production, a recording, which when finished and available for download is the only extant record (so to speak) of said song. When did it change? Well, that was a gradual process - when sheet-music sales were overtaken by gramophone sales, when live music on radio was superseded by disc-jockeys jockeying discs. But an early marker of the transition was the inauguration of electrical recording in the 1920s, the most important development in recorded sound since the invention of the phonograph half-a-century earlier. It was at that point that the gramophone record became an art unto itself as opposed to merely an acoustical capture of a performance no different from that on stage.

As it happens, the first release of an electrical recording wasn't a hit song at all, but the post-war service for the Unknown Soldier at Westminster Abbey in 1920. It wasn't altogether a successful experiment, and another half-decade passed before electrical technology was licensed to Columbia and Victor, and both record companies sat on it for another nine months until the end of 1925 - because they knew it would render their entire existing catalogues instantly obsolete, in the same way that talking pictures did to silent film a couple of years later. By 1929 only one label - Harmony - was still making acoustical recordings.

And when the gramophone record became that art unto itself it changed the very nature of popular singing. The first pop stars of the American record industry were full-voiced tenors like Billy Murray and Henry Burr. You can hear some of them in our Mother's Day audio special - after which long-time reader and reluctant listener Daniel Hollombe wrote to register his disdain:

As long as I live, I never want to hear another parlor waltz featuring an effete tenor who insists on rolling every 'R' (even the ones that aren't the first letter of the word).

But that's how they did it in those days: a vocalist was a stage singer who could pitch the song over the orchestra pit and get it to the back of the balcony. And you rolled your "r"s so that, when it reached the cheap seats, it was with every consonant intact. When you went into a "recording studio" you did it no differently. Why would you? There was no other way to sing.

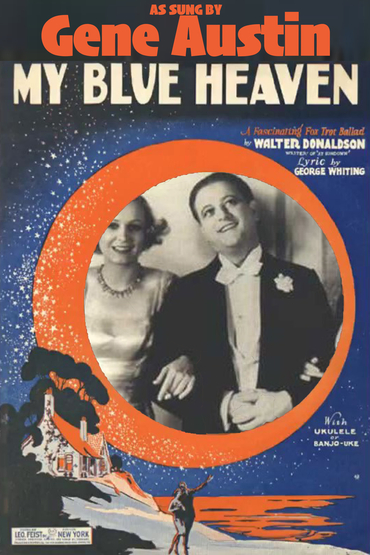

Then came the electrical microphone, and suddenly stage singing and record singing were no longer the same thing. And thus was born, via the latter technology, the "crooner". And just shy of a century ago no crooning record was bigger in America than Victor Talking Machine Company orthophonic recording 20964-A - "My Blue Heaven" by Gene Austin ("tenor with orchestra"). There were no official Recording Industry Association of America certifications before 1958, so the numbers are less precise than they are today. If you ask the RIAA why they don't retrospectively certify known smashes like "My Blue Heaven", they politely explain that the Victor Talking Machine Company became part of RCA which is now submerged within Sony BMG Entertainment, and it would require somebody at Sony deciding it was worth their while to go back through the files and pile up all the invoices and remittances from the Twenties onward, which it probably isn't. But at a time when America's population was a third of what it is now, and you couldn't download your 78s to your telephone and say, "Hello, Central, give me Justin Bieber", and only a small percentage of that population had the one device necessary to play recorded music on, Gene Austin managed to sell as many records as Ed Sheeran or Taylor Swift - and outsell almost any other of today's bestsellers. "My Blue Heaven" sold, by some accounts, over five million copies, and kept on selling in the years that followed. It was the biggest-selling record of the Twenties, and the second biggest-selling record until "White Christmas" in 1942, and the biggest-selling non-Christmas record until the monster Number One hits of the Fifties:

At which point, you may be wondering: Gene who? There are showbiz names from the Twenties that still resonate - Al Jolson or even Eddie Cantor and Rudy Vallee - but Gene Austin's is not one of them. He was born Lemuel Eugene Lucas in Gainesville, Texas in 1900, the son of Nova Lucas of Missouri and his wife Belle, the great-great-granddaughter of Sacagawea. The first songs young Eugene learned to love and sing were those of the cowboys driving their cattle down the Chisholm Trail not far from his back door. When his mother found out, she fretted that "any bolting steer could trample my son to death" and sent him off to play in town instead. He found a new kind of music to enthrall him in the house pianists of Gainesville's prostitution parlors. Belle divorced Nova and married a blacksmith called Jim Austin, who insisted Eugene take his stepfather's name. They moved to a swampy corner of Louisiana, where Gene liked neither the climate nor his new dad. At fifteen he ran away from home back to Texas, where one night at a Houston vaudeville show, on a dare from pals, he climbed up on stage and sang a song. The crowd went nuts, and the vaudeville company offered him a job.

A couple of years later, America entered the Great War, and Gene Austin signed up. When it was over over there and he returned from France, Gene opted to become a dentist in Baltimore (which for some reason reminds me of the old Howard Dietz novelty song "Baltimore MD (You're the only doctor for me)"). After cutting his (or his patients') teeth in the dentist's office, he decided to swap the tooth, the whole tooth and nothing but the tooth for nothing but the truth and justice of the University of Maryland Law School. Quickly bored by law, he hopped an Orient-bound liner and signed on as a ship's entertainer. The ship didn't find him that entertaining and transferred him to the engine room to shovel coal.

Shoveling his way back to America, he wound up in New York, and in 1924 made his first records for Vocalion. A chain of music stores in Nashville had sent up a blind harmonica-player to record some hillbilly songs, but the company figured that, while the guy's harmonica and guitar were fine, the singing wasn't. So they hired Gene to ghost his vocals. The blind guy was unhappy in New York and wanted to get back to the south, so agreed to go along with the imposture. If you come across any record labels bearing the inscription "Sung & Played by George Reneau 'The Blind Musician of the Smoky Mountains' Guitar and Mouth Harp", that's the Blind Musician of the Smoky Mountains on guitar and mouth harp but the failed Baltimore dentist on vocals:

Meanwhile, Austin got a job as a song plugger with Mills Music. One day he wrote a song with Jimmy McHugh (one of America's great pop composers: "I'm in the Mood for Love", "Sunny Side of the Street", "Exactly Like You", and many more). It has a great title:

When My Sugar Walks Down The Street

And an even better second line:

All the little birdies go tweet-tweet-tweet.

McHugh & Austin's publisher, Irving Mills, did as was his custom and cut himself in on a co-author's credit. Then he dispatched young Gene to plug the song. Which was how he found himself demonstrating the number to the Victor Talking Machine Company's singing star Aileen Stanley and their Director of Light Music, Nathaniel Shilkret. We should pause here to note that Nat Shilkret is another giant of the early recording industry now almost entirely forgotten: it's estimated he sold more than 50 million records, and indeed he's said to have made more records than anybody else ever. In 1931 he was the conductor of the first ever long-playing album, and he was a key figure in many other innovations. For example, Victor's star singer, Enrico Caruso, had died in 1921, before the advent of electrical recording. So Shilkret took Caruso's back catalogue and "dubbed" in an electrical orchestra sawing along to the dead guy's voice - a progenitor of that strange mini-genre of our own time, whereby technology brings together the living and the dead to duet: Nat "King" Cole and Natalie Cole, Frank Sinatra and Céline Dion, Édith Piaf and Andrea Bocelli, Elvis Presley and Barbra Streisand, etc.

At any rate, on this day Aileen Stanley loved "When My Sugar Walks Down the Street" and declared, "Don't bother with the others, this is just what I wanted. Thank you, young man."

Nat Shilkret, on the other hand, liked not just the song Austin was plugging but the way he was plugging it. And he suggested to the young man that maybe he'd like to sing on the record - not the whole thing, because nobody knew who the hell he was. But they'd give Aileen the bulk of the song and maybe he could chime in on the tweet-tweet-tweets:

Shilkret was intrigued by Austin's singing style and asked where it came from.

"Well, Mr Shilkret," said Gene, "when I came to New York, all the singers were tryin' to follow the great Al Jolson. I knew I could never sing as loud or perhaps as good as Mr Jolson, so since he was always talkin' about how his mammy used to croon to him, I just croon like his mammy." I believe Austin is referring to "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody":

When you croon

Croon a tune

From the heart of Dixie...

When Jolson introduced that thought, "crooning" was just a word meaning to speak or sing in a soft, low voice. Robbie Burns helped popularize the word in Scots and northern English, though its origin is Middle Dutch/Low German - "krōnen" (groan). But it wasn't yet a singing technique, never mind a nationwide craze. Nat Shilkret thought it over. "You know," he said, "we may be able to start a new style of singing." He offered Austin a contract to make records for a flat fee of one hundred dollars per number.

Again, it's worth pausing to note how unusual all this was for 1925: Gene Austin's very first record was of his very own song. He was in that sense a prototype singer-songwriter. Except that he more or less packed up songwriting and just sang whatever Victor put in front of him. He wrote only one other pop hit that's still known today: if "When My Sugar Walks Down the Street" is a fine example of the sheer fizzing jollity of Twenties pop, "(Look down, look down) The Lonesome Road" (written with Nat Shilkret) is a pseudo-spiritual passable enough to be mistaken for the real thing. Sinatra and Nelson Riddle made a great version of it thirty years after Austin:

Other than that, Gene set the songwriting to one side and for a while did as he was told: He sang "The Only Only One For Me", which sold only only twelve copies, and "Yes, Sir! That's My Baby", which sold more, and "Yearning", which was a smash. But he made the same hundred bucks for all three.

Austin renegotiated his deal with Victor and upped his pay to four grand a week plus royalties, which was quite something for the mid-Twenties. He and his wife Kathryn bought a lavish new home, and lived well. He was, though, suspicious of the record company, and became convinced that Victor was passing the best songs on to other singers - on the plausible grounds that Gene Austin's crooning could make anything a hit. There was one song in particular he wanted to record:

When whippoorwills call

And evening is nigh

I hurry to My

Blue Heaven...

Incidentally, I don't think I was aware of the whippoorwill as a bird before I was aware of him as every lyric writer's first choice in ornithology, especially at higher elevation. "Birth of the Blues":

From a whippoorwill

High on a hill...

"That Sunday, That Summer":

Newborn whippoorwills

Were calling from the hills...

Hank Williams' "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" has a "lonesome whippoorwill", but that's only because all the other whippoorwills are at the studio next door recording Debbie Reynolds' "Tammy":

Whippoorwill, whippoorwill

You and I know...

Etc.

The composer was Walter Donaldson, one of the most successful pop songwriters of his day. Donaldson had hits before the Jazz Age - "How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down on the Farm (After They've Seen Paree)?" is a novelty number for the homecoming doughboys of the Great War that endured for decades after - and he had hits after the Jazz Age: "Little White Lies" was, according to Paul McCartney, John Lennon's favorite song when they were growing up in Liverpool. But Donaldson's glory years were the Twenties, for whose raucous optimism he wrote the soundtrack: "Makin' Whoopee", "You're Driving Me Crazy", "Yes, Sir! That's My Baby", "My Baby Just Cares for Me", baby song after baby song.

One day in 1924 Donaldson went to the Friars Club in New York to play billiards. But the table was occupied. So he sat down in an easy chair to wait and, to pass the time, composed a 32-bar tune. A minor vaudevillian, George A Whiting, liked it, and, notwithstanding its peppy effervescence, penned a rather fragrant lyric of domestic bliss:

A turn to the right

A little white light

Will lead you to My

Blue Heaven...

The musicologist Alec Wilder found things to admire in "At Sundown", "Love Me Or Leave Me" and many other of Walter Donaldson's songs. But not "My Blue Heaven", which is dismissed magisterially: "There is nothing of any musical interest to mention."

You can sort of see what he means - the upward phrases of the main theme; the descents of the middle-eight: it's all very efficient, but, if the billiard table hadn't opened up, maybe he would have given it another go, and polished this or complicated that. And for three years the public seemed minded to agree. George Whiting sang it in his act, and it went nowhere. "Blue Heaven" means that it's heavenly bliss and it's twilight. It's so familiar a title today that we don't even think about it, but it's very particular and I wonder if, in the hands of a clunky vaudevillian, it was just too sensitive an image to put over.

But somewhere in those three years Gene Austin heard the song, and its evocation of connubial harmony spoke to him:

You'll see a smiling face

A fireplace

A cozy room

A little nest

That's nestled where

The roses bloom...

He wanted to record it, and he wanted it released. Victor couldn't see the point. In the hyper-present-tense of the music biz, "My Blue Heaven" might as well have been Gregorian chant: If a song hadn't done anything in its first three years, it was never going to. So Austin put his foot down. He told Victor he wouldn't do another session unless the company released "My Blue Heaven". Nat Shilkret caved, and "My Blue Heaven" was scheduled for September 14th 1927.

They did three songs that day: First came "My Melancholy Baby", and then "Are You Happy?". "My Blue Heaven" was to be the last song on the session. Instead, after "Are You Happy?", the band picked up their instruments and headed for the door. Austin was furious and demanded to know what was going on. Shilkret apologized and said he hadn't known at the time he made his promise that the musicians had another date. But not to worry, they could do it another time. No way, said the singer. As he told it:

I grabbed an old guy with a cello and talked him into standing by. Then I grabbed a song plugger who could play pretty fair piano. And the third fellow I got was an agent who could whistle bird calls and that sort of thing...

Where there's a whippoorwill, there's a whippoorway. Having assembled his ad hoc "orchestra", he went back into the studio and made one of the biggest-selling records of the century.

And, if you think Gene Austin's story is one of those too-good-to-be-true yarns, listen to that record (up above) - a subtle, tender, intimate vocal with a great plonking accompaniment that might as well be volunteers from the audience, or random derelicts from the line at the soup-kitchen: "My Blue Heaven" by "tenor with orchestra". Imagine what the tenor might have sold had Nat Shilkret's orchestra not headed for the door.

Here he is years later with Les Paul on guitar:

You can tell George A Whiting isn't a professional lyricist. The giveaway is:

Just Molly and me

And baby makes three...

A serious Tin Pan Alleyman would never have written that - because "Molly and me" restricts its singing to male vocalists. Of course, female singers do sing it. If memory serves, Lena Horne used to modify it to "Just my baby and me/And Fido makes three...". For Gene Austin, that couplet had particular appeal - until one awful day in St Louis when, holding a freshly pressed copy of "My Blue Heaven" to take home to his family, he received a telegram informing him of the death of his newborn son.

Whatever the limitations of the accompaniment, you can still hear in "My Blue Heaven" why, in that first decade of microphone singing, Gene Austin sold over 80 million records, and influenced, even as tenors yielded to baritones, not only Bing Crosby but Frank Sinatra. Nat Shilkret was right: It was "a new style of singing", albeit not one to everyone's taste - Cardinal O'Connell of Boston denounced crooning as "base" and "degenerate", and The New York Times confidently predicted it would "go the way of tandem bicycles, mah jongg and midget golf". But the old-school singing never returned. Gene Austin was one of the first vocalists to treat the microphone as an instrument, and that understanding proved more lasting than tandem bicycles.

He lived till 1972, long enough to hear almost everyone else take a whack at "My Blue Heaven", including Fats Domino, who claimed it for the rock'n'roll crowd and re-accented the title - not "My Blue HEAVen" but "My Blue Heav-UN". Who knows what Gene Austin made of that. But he had a high degree of tolerance for his biggest-selling song. In his final years, the man who began his formal recording career by mimicking bird sounds - "Tweet-tweet-tweet" - to Aileen Stanley kept a bird who mimicked Gene Austin. Visitors to his home were greeted by a parrot who squawked:

When whippoorwills call

And evening is nigh

I hurry to My

Blue Heaven...

At which point the parrot would conclude his performance with a final squawk:

Why don't we sell this damn bird!

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

If you're a Steyn Clubber and you don't find the above in the least bit heavenly, blue or otherwise, feel free to sock it to him in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page. For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.