There are films that I enjoy more as a photographer than as a cinemagoer. I don't mean the kinds of pictures that win Oscars for epic landscapes full of sunsets, or special effects extravaganzas where much of the film was created in a computer. I'm talking about films that make me want to hit pause and appreciate a bit of composition or lighting, or inspire me to turn the TV off altogether and head outside with my cameras. I'm talking about a film like Michelangelo Antonioni's L'Eclisse (The Eclipse).

The film was released in 1962, near the end of the first great period of his career in Italy, and was the final film in a trilogy of black and white pictures that included L'Avventura (1960) and La Notte (1961). Antonioni was one of the leading lights of art house cinema, alongside directors like Fellini, Bergman, Ozu, Rossellini, Truffaut and Godard, and helped make words like "alienation" a staple of both academic and popular movie criticism. (Bergman and Antonioni would die hours apart in 2007.) He has a lot to answer for – critic Andrew Sarris coined the word "Antoniennui" to describe his work – and that makes it hard to rediscover what made his films so resonant when they were released.

The film begins with the title and credit sequence – stark white letters on a black background – and a blast of pop music on the soundtrack. This is "Eclisse Twist" by Mina, the Italian pop singer (born Anna Maria Mazzini) who was simultaneously the rough Italian equivalent of Shirley Bassey and Lesley Gore, and it's the only piece of non-orchestral music in the film, the remainder comprising Giovanni Fusco's dissonant score. But don't forget about Mina, because she'll be important later in the story.

The first scene is a break-up; it's dawn on a Monday in June of 1961 (the time and year is expressly noted by a title card) and Vittoria (Monica Vitti) is breaking up with Riccardo (Francisco Rabal) in his apartment. There are no raised voices or arguments; the relationship has entered an entropic state, so much that at one point Riccardo sits motionless and zombie-like in his chair while Vittoria continues her long, tentative exit from the apartment. If you managed to avoid marriage for most or all of your twenties, it's all painfully familiar, a love affair run out of steam, with Vittoria signalling her need to escape by opening the window curtains and staring desperately outside.

What Vittoria sees through the window is the EUR, the planned neighbourhood built around the grounds of the Esposizione Universale Roma, the 1942 World's Fair that Italy was supposed to host until Mussolini declared war on half the world. Despite being bombed during the war, Italy decided to retain and repair the area and finish developing it with modernist buildings that harmonized with the fascist architecture.

Bernardo Bertolucci would also showcase the neighbourhood in The Conformist (1970), and Antonioni lavishes long, wide shots on the landscape and landmarks of the EUR, like Il Fungo, the mushroom-shaped water tower/restaurant that looms over Vittoria and Riccardo as he walks her home to her apartment in a tidy modern block of flats. The EUR was a planned development, but it wasn't meant to warehouse workers being relocated to the suburbs as much as it attracted a prosperous new, young middle class who didn't want to live in Rome's cramped, ancient downtown.

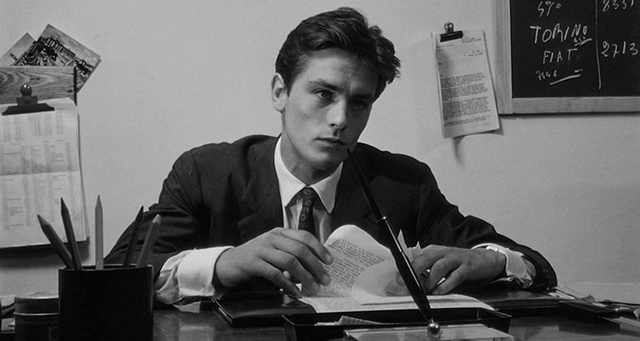

The film follows Vittoria over the summer, as she travels between the EUR and downtown Rome, where she visits the stock exchange building built on the foundations of a temple to the Emperor Hadrian. She's there to see her mother, a war widow caught up in what we'd call day trading, speculating on stocks in the hope of making quick money. While there, she meets Piero (Alain Delon), her mother's handsome young stock broker.

Most of the film until Vittoria and Piero begin a romance is episodic, following Vittoria around while she occupies her days evading Riccardo and spending time with friends. The scenes in the stock exchange are the most frantic; Antonioni is clearly fascinated with the rituals and bellowing frenzy of the pre-digital trading floor, with its paper notepads and telephone booths and manually-operated scoreboard for stock prices.

Like most movies about the market, there's very little sense that Antonioni actually understands how shares are traded as much as he loves the high drama and emotional turmoil of the players as they lose millions during one day of heavy losses. It's here that the camera shifts focus from Vittoria to Piero, spending a fraught night with him as he tries to collect on the losses incurred during the day.

The scenes with Vittoria and her girlfriends Anita (Rossana Rory) and Marta (Mirella Ricciardi) would probably cause Antonioni's film no end of trouble today. Marta's husband owns a farm in Kenya, and their apartment is filled with hunting rifles, African crafts and souvenirs and photos of natives; she professes her love for the place while describing the restive population, primed with post-colonial unrest, as "monkeys." Vittoria seems to struggle to contain her disapproval of Marta's racism, but then this happens:

It's hard to tell whether Vittoria's blackface dance is an expression of her own racism or a way of living out the envy she expresses for the women in Marta's pictures. Antonioni's camera doesn't flinch, and the scene is unsurprisingly problematic for young viewers of the film today, like the reviewer on the Edinburgh Cinema Club blog who describes it as a "dreadful display."

"Watching this scene left me uncomfortable," they write. "We are left imploring Vittoria to grow the hell up." Oddly, it's the racist Marta who's unhappy with Vittoria's little show, telling her "That's enough. Let's stop playing Negroes." The whole scene stands out painfully today, but it's hard to say whether contemporary audiences were as shocked. After all, it has to be remembered that no less than the Prime Minister of Canada thought it suitable to don blackface at a private school gala as late as 2001.

What we do know is that Vittoria is unhappy, with a deep sense of melancholy that can't be simply tied to her breakup with Riccardo. We only see her escape this lingering funk three times – once when she's running after Marta's escaped poodle and stops, standing transfixed by a line of empty flagpoles, rattling and vibrating in the wind under the moonlight.

The other time is when Anita's husband takes them on a ride in his new airplane to Verona. The scene plays like a bit of a travelogue, Vittoria visibly thrilled with the view from the plane's windows as they circle Rome's ancient monuments and later land at the Aero Club Verona. "It's so nice here," she tells Anita.

Following Vittoria around becomes a tale of two Romes. There's the old city and its narrow streets, with people living on top of each other as they have for two thousand years. Indoors she's either in the tiny rooms of her mother's flat or wandering through the maze of grand, art and antique-filled spaces of Piero's family apartment. She looks out a window onto the adjacent cobblestone piazza and its customary accessories – a church, a corner café, a fountain. It's so typical it could be clip art.

This is contrasted with the broad, sun-filled expanses of the EUR, where the streets are always empty except when a crowd gathers to watch as Piero's little Alfa Romeo sports car is pulled out of the lake. It had been stolen by a drunk the night before; the drunk's body is still in it. In the old city everything is being repaired, while in EUR it's under construction.

It's customary to call the rural, industrial and suburban panoramas in Antonioni's films "wastelands," and the setting of films like L'Eclisse a landscape of alienation. They're certainly the places where characters played by his muse, Vitti – Vittoria in L'Eclisse, Claudia in L'Avventura, Giuliana in Red Desert – are visibly troubled. But as a photographer I have a hard time endorsing this simplistic take on his films.

There's a palpable fascination with the EUR and its apartment blocks, spotless municipal buildings and unfinished landscaping that I don't buy as unease or revulsion. Quite the opposite; as someone who grew up in a city that nobody would count among the world's loveliest, I developed an appreciation for what's called "ugly beauty" – the unlikely power and appeal of those rough places where the city and the country meet and lock themselves in a long, slow battle for domination. Antonioni was born in Ferrara, in the industrial north of Italy, near the River Po, and began his directing career in 1943 with Gente del Po, a short film about poor fishermen who worked on the river.

In the last few years a new term was coined to describe the sorts of uneasy, transitional landscapes that Antonioni favors in his films: liminal spaces. The subjects can be anything from empty malls to the stark hallways, common areas and corridors of schools, hotels and airports, highway overpasses and ploughed fields – the kinds of spaces, usually unpeopled, that we pass by and through regularly, sometimes every day, without really noticing.

Some artists create scenes that could only exist in a mash up of old ads and video games. YouTuber and Washington Post columnist J.J. McCullough describes it as "Middle Class Millennial Nostalgia Art," pinning its appeal on the lingering childhood consumer fantasies of a generation that has never known real want, and grew up as the market for newer and better toys every birthday and Christmas.

This obviously couldn't apply to Antonioni – born in 1912 – or the audience for films like L'Eclisse, who had recently lived through the postwar economic recovery. But that doesn't mean that there isn't some sense of indefinable nostalgia that her surroundings trigger in Vittoria – a place stuck between the past and the future. It's obvious that the EUR isn't full of ruins, but with so much of it under construction – like the block of flats, covered in scaffolding, where Vittoria and Piero regularly meet – it isn't hard to imagine the day when it will be overtaken by the grass, trees and water it paved over and fenced in.

Which brings us to Vittoria and Piero and the relationship the whole film builds – slowly, very slowly – to set in motion. They orbit each other tentatively at first, Delon's Piero pursuing Vittoria more than vice versa; his unashamed interest in money and the value of things would be a deal-breaker for Vittoria if it weren't for one, undeniable fact: they are exponentially the most attractive people in the whole film.

Antonioni had a proclivity for filling his movies with beautiful people – the better, one presumes, to help the angst go down. La Notte, his previous film, added Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau to Vitti, and Blow-Up, his first film outside Italy, would pair David Hemmings with a young Vanessa Redgrave and half of the fashion models in Swinging London. It's hard to decide who's prettier – Vitti or Delon – and the lingering question for most of L'Eclisse isn't so much "Will they or won't they?" as much as "Who wouldn't?"

Piero leaves his natural habitat in Rome's crowded ancient centre to pursue Vittoria in the wide open spaces of the EUR, getting his car stolen for the trouble. He finally brings her to his parents' vast apartment, where they pursue each other through the rooms until they can't deny their attraction to each other any longer. But there's something wrong, some inability to let themselves give in to love and longing, which Vittoria sums up by telling Piero "I wish I didn't love you, or that I loved you much more." Once again, and like the world around her, she's stuck in a transitional space between two places.

They spend a weekend afternoon in Piero's empty office, where he's taken all the phones off the hooks to give them some privacy. The chemistry between the actors here is astonishing; Vitti is suddenly playful and vivacious, unlike Vittoria for much of the preceding film, and apparently more like the actress' own personality off screen. It's probably why there's an elation and release in the scene that the movie denies us until then.

But the ringing of one overlooked phone breaks their reverie, and they make an agonizing farewell, promising to see each other later that night, and then forever after that. You can't help but want to believe them despite yourself, and the last seven minutes of the film is one of the most famous – even infamous - endings in movies.

Antonioni's camera returns to their meeting place in the EUR, and while the sun slowly sets, searches for Vittoria and Piero. It finds a head of blonde hair that turns out to be another woman, and lingers on the places where we'd seen them before. Familiar extras reappear – a nurse pushing a pram, a man riding a sulky – and a bus empties its passengers onto a corner, but Vittoria and Piero never show.

The whole sequence is about absence, lingering on voids and negative spaces in its search for the lovers. The camera holds on a streetlight blazing against the darkening sky and the film ends. In America, some theatre owners found the ending so unsatisfying that they'd cut it from the print.

Four years after the release of L'Eclisse the singer Mina – you remember her – released "Se Telefonando," a single that became one of her biggest hits in and outside Italy. The onetime "Queen of Screamers" worked with composer Ennio Morricone, then famous for his spaghetti western soundtracks, on a song that married Phil Spector's "Wall of Sound" to a tune that wouldn't be out of place in a Bacharach and David songbook.

The lyrics by Maurizio Costanzo and Ghigo De Chiara are about the end of love (and pardon the inelegant translation from Italian):

If calling you I could say "goodbye",

I would call you.

If seeing you again

I would be sure that you don't suffer,

I would see you again.

But I cannot explain to you

That our love is just born

and has already finished...

Five years ago a YouTube account run by "ronny spandau" uploaded a video of "Se Telefonando" cut to shots from L'Eclisse (and a couple from L'Avventura), making explicit what had already been presumed for years: that Mina's hit single was just Antonioni's film, or maybe a second shot at the theme song that should have been there instead of "Eclisse Twist". Condensed from just over two hours to less than three minutes, it distills Vittoria and Piero's abandoned romance into something ecstatic and almost unbearable - just the yearning and longing and rush of love's first intoxicating minutes.

It makes it easy to remember why young women who saw L'Eclisse imagined themselves in Vitti's chic shift dresses, walking through the wide streets of the EUR, even if they'd seen how the film ended. More poignantly it reminds us how, in the first intoxicating flush of reciprocated passion, we imagine ourselves to be as beautiful as Vittoria and Piero. I actually enjoy it more than Antonioni's film; I'll certainly watch it, over and over, even if I never make it through L'Eclisse again.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.