There's a trope that sticks to nearly every Christmas movie like a half-sucked candy cane to a fuzzy new sweater – the power of "Christmas Magic" to influence and transform outcomes for the better. It's what draws a whole division of ex-GIs to a bankrupt New England inn for a reunion, lets a despairing man discover how much worse the world would be without him, and turns a miserly curmudgeon into a jolly philanthropist.

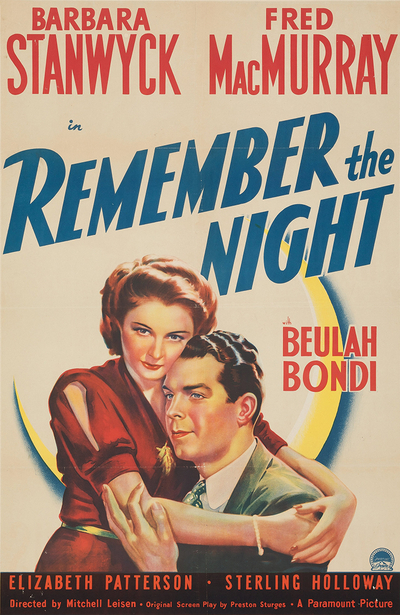

It's almost impossible to escape the not-so-invisible hand of Christmas Magic, even in a film as avowedly misanthropic as, say, Bad Santa (a personal favorite). But if you're still looking, a great place to start is 1940's Remember the Night, a Mitchell Leisen film made from a script by Preston Sturges. Oh, there's definitely some Christmas Magic in play – the sort that's apparently in abundance whenever a city slicker returns to his rural roots, complete with a creaky off-grid homestead, guileless hicks and doting female relations radiating small-town virtue.

At the same time, however, you're recommending a film that's essentially a romantic comedy reimagining of The Maltese Falcon, where Humphrey Bogart tries to botch the case, and Mary Astor turns herself in to the cops and asks Bogie to wait for her when she gets out. There's plenty of sentiment and tears, but working from a Sturges script (their second and last collaboration after 1937's Easy Living) cuts the treacle with plenty of vinegar.

Leisen begins the film with an economical sequence that begins with a giant bauble on the gloved wrist of Lee Leander (Barbara Stanwyck) in a Fifth Avenue jewellers, then follows her to a Third Avenue pawnshop where she's nabbed and briskly put in front of the court and assistant district attorney Jack Sargeant (Fred MacMurray).

Jack is a rising star in the New York District Attorney's office – undefeated in court – and knows that getting a conviction from a jury on a woman just before Christmas is a tall order. His job is made easier by Lee's histrionic lawyer, who weaves a tale of tragedy and bathos that even she finds fantastic. (Everyone jokes about her lawyer's onetime career on the stage, and Willard Robertson, the actor playing him, was in fact a lawyer from Texas who turned to acting.)

The key to his defense is that Lee was somehow hypnotized by the glinting stone in the bracelet, a point Jack seizes on to argue that a qualified medical expert in hypnotism is required to attest to this wild theory, and he insists that the case be held over till one is available in the new year, at which point he's more likely to sway a jury.

Having won a remand in the case, Jack feels guilty about putting Lee in jail over Christmas, so he asks Fat Mike, a bail bondsman, to get her out for the holidays. But like everyone else Mike assumes that Jack, a bachelor, has his own reasons for this, and delivers Lee to Jack's apartment like an early Christmas present. Jack, still a Midwestern boy at heart, is shocked by this immoral presumption, but for her part Lee takes it in stride, her reaction hinting that she's seen this sort of thing before, and it could have been worse.

Like almost any romantic comedy from this period, screwball or otherwise, there's no shortage of improbabilities the audience is expected to accept along the way. But there's nothing in the way Leisen and Sturges presents this situation that makes you assume that those audiences would be shocked to learn that bail bondsmen are working as procurers, pimping out comely defendants for assistant DAs. This is the sort of thing that should have caught the attention of the Production Code, but Preston Sturges was a genius at getting these cynical spitballs past the censors.

Yesterday, today or tomorrow, you can never go wrong by assuming that nobody likes lawyers.

MacMurray does a much better job as a successful, even smug DA than he did as the struggling and idealistic lawyer in True Confession three years earlier. He offers to take Lee for dinner in a swank nightclub before he has to start the long drive home to Indiana for the holidays, and tries to understand her motivations for what is apparently a long career as a thief.

"I don't think you ever could understand because your mind is different," Stanwyck's Lee explains to him. "Right and wrong is the same for everybody, you see, but the rights and the wrongs aren't the same. Like in China, they eat dogs..."

"That's a load of piffle," says Jack.

"They do eat dogs!" replies Lee.

"I mean your theory," Jack responds.

If the earlier scenes with MacMurray's Jack and his eye-rolling, blues-singing manservant Rufus (Fred "Snowflake" Toones) didn't do it, this exchange guarantees a minute of pained explanation by the host if TCM screens Remember the Night.

Jack has a hard time understanding why Lee steals without apparent qualms, and is ready to cut her loose until they discover that they're both Hoosiers, who grew up within driving distance from each other. He offers to take her home to her family for the holidays, despite her admission that she hasn't seen her mother since she ran away.

The two of them end up lost in Pennsylvania thanks to detours and road construction, and end up sleeping in a farmer's field. The gun-toting hick insists on charging them with illegal trespass and brings them in front of the justice of the peace, who resents these arrogant, presumptuous New Yorkers as much as the farmer. They're about to get thrown in the county jail when Lee sets a wastepaper basket on fire and gets Jack to make a runner with her, turning both of them into fugitives from justice in Pennsylvania at least.

Keen movie buffs know that this is the first of four films that would team Stanwyck with MacMurray, and that just four years later that they'd star in Billy Wilder's landmark film noir, Double Indemnity. Sturges had written his screenplay with Carole Lombard cast in the role of Lee, so it was pure luck that teamed Stanwyck and MacMurray together, with results that yielded undeniable onscreen chemistry.

Stanwyck wasn't an actress known for comedy as much as a string of roles in dramas as the fallen woman – sexually experienced damaged goods with a tragic end just over the horizon, going back to pre-Code films like 1933's Baby Face. Stella Dallas (1937) won Stanwyck her first Oscar nomination and made this her effective onscreen persona, so even she was shocked when Sturges told her, after watching her on set during Remember the Night, that "I'm going to write a great comedy for you."

He'd deliver, a year later, with his third film as a director – The Lady Eve.

Like Mae West before her, Stanwyck brought the fallen woman into comedies with a vengeance, and Sturges provides the necessary backstory for her particular innovation when Jack and Lee make a late night visit to her remarried mother – a cold and unforgiving woman who refuses to accept her daughter back into her house. Touched by the poverty, emotional and otherwise, of her upbringing – Lee's childhood home is literally on the wrong side of the tracks, shot with deep shadows out of a horror film – Jack offers to take her home to his family for the holidays.

Stanwyck was no pinup, but she was attractive in a plausible, real-world way, with pretty legs that were showcased in countless roles. She exuded a taunting sexual availability tempered by wariness and obvious street smarts, earned with palpable experience. The actress never attended high school, after a tough early life that saw her orphaned at twelve, working as a chorus girl in the Ziegfeld Follies at sixteen, a Broadway star at nineteen and married at 21. Studio publicists often did their best to buff up the backgrounds of their female stars into pastel soft focus; it would have been futile to do so for Stanwyck, so integral was the assumption of a troubled past to her appeal.

Not everything Stanwyck made was a masterpiece, especially in the '30s, but as James Harvey writes in Romantic Comedies in Hollywood from Lubitsch to Sturges:

"No matter how poor the movies, Stanwyck went on being impressive somehow. She never seemed foolish or strained, and she became over the years a powerful accumulating presence for audiences, one of those stars whose existence seemed almost to define the movie experience at its most satisfying and sustaining. She was both sensible and sad – a conjunction that was noticed early on in her career. 'There is something,' said the New York Herald Tribune review of Shopworn ('That unfortunate, but descriptive, title') in 1932, 'about the simple, straightforward sincerity of Miss Barbara Stanwyck which makes everything she does upon either stage or screen seem credible and rather poignant.'"

The Sargeant homestead is the sort of cluttered museum of Victorian lower middle class comfort – all hurricane lamps and antimacassars and framed needlepoint samplers – that Harvey describes as "not just evocations of the past but the furniture of the American mind," at least before the midpoint of the century, when living memory had made the period between the end of the Civil War and the start of the First World War a sort of paradise lost.

Lee is warmly welcomed by Jack's mother (Beulah Bondi), his spinster Aunt Emma (Elizabeth Patterson) and their comic hired man Willie (Sterling Holloway), the hayseed mirror of Rufus. The warm embrace of the past – familial and social, once the unmistakable sign of a healthy community in movies – culminates in the parlour, around the piano, where Lee follows up Jack's halting rendition of "Swanee" (no, really) with "A Perfect Day."

Unknown today, it was a hit for Carrie Jacobs-Bond when it was published in 1910, the sort of shamelessly sentimental song that was more popular thanks to sheet music than recordings. After she adds her harmony to Willie, the rest of the family joins in, evoking a scene of warmth and acceptance that begins to draw Lee out of her hardened shell and closer to Jack.

Jack's mother presents Lee with a busy social schedule for the holidays, from apple bobbing to a church bazaar to a hick-themed barn dance, and the past physically envelopes Lee when she's dressed up – corset, crinolines and all – in one of Jack's mother's old party dresses, packed away back in 1908, when Teddy Roosevelt said he wouldn't run for a third term.

Despite their obvious attraction, and Jack's mother's warm welcome, it's made plain to Lee that Jack has worked hard to achieve his success, and that falling in love with a career thief would ruin it all. The pair detour through Canada to avoid Pennsylvania, and at Niagara Falls Jack suggests that Lee jump bail and stay in Canada, where he'd help her out with money and even find a way to join her.

Back in New York Jack tries to lose the case by aggressively questioning Lee and bullying the jury. She knows what he's doing and tearfully changes her plea to guilty. The judge asks her why she'd do such a thing, and she replies that it's "because I am guilty. When you make a mistake you've got to pay for it. I don't know why I never learned that."

Having followed Lee back home, the audience knows precisely why, and her sacrifice is a moment of redemption, an attempt to be, as Jack puts it, "all square."

So not a typical Christmas picture, if you're looking for an unalloyed happy ending that fades to the credits with a crescendo of strings and jingle bells. Leisen and Sturges end Lee and Jack's story with the final scene and its "complicated feeling," as Harvey describes it. It's a cliffhanger of sorts, but not one that resumes when Lee leaves the big house.

"The movie itself makes us feel that there's more to be said for Stanwyck's lady thief, even for her way of life, than this film, with its formulaic regeneration at the end, ever really manages."

For Harvey the sequel was The Lady Eve, but for the rest of us it could continue with Stanwyck and MacMurray as the adulterous murderers in Double Indemnity and, if you want to keep going, the same actors in Douglas Sirk's 1956 melodrama There's Always Tomorrow, where she's a widow and he's unhappily married and they have an almost-affair that ends with a mature but heartbreaking choice.

Or if you prefer Christmas Magic there's Stanwyck as a proto-Martha Stewart in 1945's Christmas in Connecticut, lying about a perfect home and family while being unable to boil an egg. It's far more upbeat than Leisen and Sturges' movie, but I actually prefer Remember the Night right now, when it's so hard to forget that, whatever escape the holiday might bring, we're facing some serious choices about our future after Boxing Day.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.