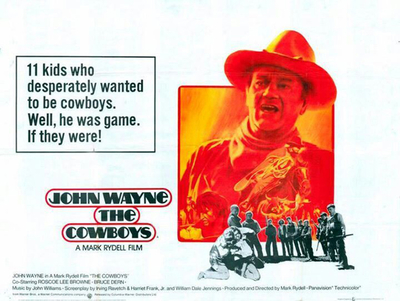

At the risk of spoiling a 50-year-old film, the most efficient way to introduce The Cowboys, a 1972 western produced and directed by Mark Rydell, is that it's the one where John Wayne gets killed. To be sure, Wayne died in more than just one film, but of the ten where he does, five of the deaths are offscreen and one of them is so early in his career that his unfortunate character doesn't even have a name (1933's Central Airport).

But The Cowboys was notorious for Wayne's death, one full act before the film's finale, as it had been over a decade since the Duke bought the farm in a film, playing Davy Crockett in The Alamo, making a heroic exit by blowing up the fort's powder magazine and a whole bunch of Santa Anna's troops. He'd die again onscreen, of course – four years later in The Shootist, his final film. But Wayne's death in The Cowboys happened at a cultural moment when killing John Wayne wasn't just a plot twist but a political statement, or at least that's how it was interpreted during the long twilight of the '60s that seemed to last until the middle of the '70s.

Following the ironclad rule that there's no such thing as a period film as much as a movie about the time when it was made, dressed up in costumes, The Cowboys is a story about generations – one receding, the other emerging. Even if events offscreen didn't underline this theme, it would be hard to miss from the elegiac tone and the forlorn mood that seems to have overtaken the older characters.

Wayne plays "Wil" Andersen, a sixty-year-old Montana rancher whose ranch hands desert him when news of a gold strike empties out the territory with fortune seekers. He has a herd of cattle that need to be driven to market four hundred miles away, and nobody to do it until a friend in nearby Bozeman tells him to try his luck at the local schoolhouse.

Wil is a hard man, made harder by losing both of his sons when they were still young men. "They went bad – or I did," he admits later in the film. It's hard to miss that he's being given a second chance when he takes on eleven boys, none of them older than fifteen, to drive over a thousand cattle through a landscape that ranges from prairie scrub brush to forest to mountain foothills.

His initial reluctance is overcome by other characters reminding him that he was still a boy when he did his first cattle drive, but Wil is sure – as most older generations are, throughout time – that he was somehow tougher, more resilient – in a word, better – than any young person now.

The cattle drive east from Bozeman to Belle Fourche, South Dakota (almost exactly four hundred miles in the real world, to give credit to the film's producers and William Dale Jennings, author of the book the film is based on), takes Wil and the boys past the site of the Little Bighorn massacre, where they find the bleached bones of Custer's troops, still lying on the battlefield.

This places the film's setting at the end of the 1870s at the earliest, just a decade before the 1890 US census that's considered the official closing of the frontier, at least according to the Frederic Turner Jackson thesis that informed so many of the movie westerns that would come years later. (The voiceover on the film's original trailer tells us it's 1878.)

"It's a different day," Wil's wife tells him at the start of the film, and this only adds to the sense of an era passing, and with it the shared history and experience of a generation that includes a vast, bloody war that marked their lives forever and changed history – a war still vivid in their memories, but already ancient history to the young.

Director Mark Rydell was not one of the Hollywood veterans Wayne made his reputation with – legends like John Ford, Howard Hawks or journeymen like Henry Hathaway – but a former soap opera actor and television director who made his feature debut with The Fox in 1967, a Canadian film based on D.H. Lawrence's novella about a romantic triangle with a lesbian base.

As a director, Rydell was very much a man of his time; after The Cowboys he made Cinderella Liberty (1973), a drama about prostitution and miscegenation with James Caan and Marsha Mason, and Harry and Walter Go to New York (1976), a period comedy starring Caan, Elliott Gould and Diane Keaton and a notorious bomb. He recovered with The Rose in 1979 – the Bette Midler vehicle that combined Janis Joplin with A Star is Born – and On Golden Pond (1981), which cast Henry and Jane Fonda as father and daughter and won Oscars for the former and Katharine Hepburn.

This would be the peak of his career, but in 1971 he was still a director trying to make his reputation, and a self-described liberal who was wary when the prospect of casting John Wayne in his film became a possibility. (He wanted George C. Scott for Wil.) In a bonus feature included with the 2007 deluxe DVD reissue of the movie, Rydell remembers meeting Wayne on the Mexican set of Big Jake, expecting a fire-breathing right-winger and meeting a humble actor who practically begged him for the role of Wil.

In May of 1971, when the film was still in production, Wayne gave an interview to Playboy magazine that caused a scandal at the time, and then again three years ago, when it was "rediscovered" just as cancel culture emerged to wreck careers for both the living and the dead. (Mahatma Gandhi joined Wayne on the list of those to be posthumously canceled that year.)

In the interview, Wayne described Midnight Cowboy as "a story about two fags" and told the interviewer that "I believe in white supremacy." It was unsettling to people who'd grown up watching his films, so you can imagine the effect it had on people born long after Wayne died, who had probably only ever encountered him in parodies whose context they found baffling.

A Guardian article from 2019 about the Playboy interview's "rediscovery" says that "revisiting Wayne's views is important: we should be mindful to revise and decolonise the film canon, and it's essential to reassess cinema's heroes in the light of our shifting politics."

So far, so Guardian.

"On the other hand," writer Caspar Salmon continues, "it's possible to feel a certain weariness about a new right-on mindset finding fault with, of all people, John Wayne. Who next, Charlton Heston? Ronald Reagan? Pity the modern film buff who happens, during their internet travels, upon Frank Sinatra's ill-advised links to organised crime! Seeing a brouhaha erupt over these comments shows that there exists in our discourse a certain incuriosity about the past, a lack of education on movie history, and a want of nuance in understanding politics in the golden age of Hollywood."

It's always shocking to read the Guardian and find something that sounds reasonable. At the same time it's strange to feel a tug of nostalgia for 2019, when it was possible to think you could resist the growing craze for social and cultural defenestration and not expect your own imminent cancelation.

Even over thirty-five years later, Rydell still talked about the political gulf between himself and Wayne, the reaction to the Playboy interview, and the on-set clash that he's still surprised never happened.

For the boys, Rydell cast a group of unknowns, some actors, some young rodeo veterans who could handle the film's action scenes. The most notable of them all was Robert Carradine, the younger brother of Keith and David, and son of legendary character actor John Carradine. It was his first role, one that he'd follow up with a small one in Mean Streets, before hitting the big time by starring in the Revenge of the Nerds films.

The boys manage to learn enough to begin the cattle drive with Wil and Nightlinger, a hired chuck wagon driver played by Roscoe Lee Brown, whose sonorous, theatrical baritone constantly threatens to steal the film from Wayne. Black characters with major parts in westerns weren't that unusual by the early '70s – Woody Strode was a regular in John Ford's films, and Sidney Poitier had starred in Duel at Diablo (1966) before releasing his first film, Buck and the Preacher, the same year The Cowboys came out, starring in it alongside Harry Belafonte and Ruby Dee.

Modern audiences would find the reaction to Brown's Nightlinger in The Cowboys triggering; while Wil never uses racial epithets around him, the boys casually call their worldly cook the n-word, alongside the film's villain – Bruce Dern as "Long Hair", in full psycho mode.

Young people today find the word shocking, even unendurable, in almost any context. It's hard to convince them that it actually was shocking to hear in 1972, even at a time when it was still used casually, and not long after it was commonplace, but before it joined the list of words with unaccountable magical powers.

But nobody hearing the boys say it to Nightlinger's face thought the film was making a judgment on them as racists as much as naïve and uncouth boys, born just after the end of the US Civil War. But when Dern's Long Hair uses the word it's plainly one of the red flags signaling that he deserves whatever punishment the film should see fit to visit upon him before the credits roll. (Dragged to death by his horse, if you're curious.)

Dern's Long Hair – his character is named Asa Watts, but the credits notably call him Long Hair – is introduced as an ex-convict who tries to get work on the cattle drive with Wil, and returns later in the film at the head of a gang of rustlers shadowing Wil, Nightlinger and the boys. In retrospect, Dern said that playing the man who killed John Wayne damaged his career for many years to come; his reputation was tainted with casting directors and Wayne's fans would accost him on the street, calling him names and saying "You killed my buddy!"

Dern's onscreen offing of Wayne is notorious: after being bested by the older man in a fistfight, the cowardly rustler takes a gun from one of his men and shoots Wil in the back - not once but three times - before leaving him to die, gut shot, abandoned in the wilderness with the boys. Dern recalled that the Duke was drunk when they filmed the scene late one night, and told Dern that "they're gonna hate you for this."

True, Dern replied, "but at Berkeley I'll be a f**king hero!"

It's hard to imagine that The Cowboys would get made today, even if we still made westerns, and not only because its very contemporary anti-racism would be mistaken for racism now. There's also its length – over two hours, padded out with John Williams' symphonic hoedown overture and intermission music – and leisurely pace, complete with an interlude where two of the boys are briefly tempted by a mobile brothel run by Colleen Dewhurst's madam, a scene that alludes to the sirens of Homer's Odyssey, included for audiences who'd actually get the reference.

It's hard to argue that the film doesn't fall apart after Wayne dies, as satisfying as it is to see Brown and the boys exact their vengeance on Dern and his gang. Reviewing the film for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert complained about "the final shootout, during which every one of the range-wise, hardened, experienced, jailbird gunmen is killed and not a single kid gets nicked, even. Let me tell you, it takes a lot of heroic music to paper over this ending."

Time magazine and Pauline Kael in the New Yorker were critical about how violence and revenge were crucial in the boys' coming of age. "There are good men and there are bad men; there are no crossovers or nothing in between," Kael wrote about Wayne's Wil. "People don't get a second chance around him; to err once is to be doomed." While there's no doubt Kael was a brilliant, influential critic, she could sometimes write about genre films as if she'd never seen another example of its type before.

In The Western: From Silents to the Seventies, their authoritative book on the genre, George Fenin and William K. Everson call The Cowboys one of Wayne's "traditional 'good and right' films," dismissing it as a "glib tale" that was "blessed by the Establishment and the Parent-Teacher Association." It's sometimes stunning how much the present is reviving the intensely polarized politics I remember from the '70s, albeit with many roles reversed and goal posts moved miles downfield.

By the turn of the '70s nobody was making westerns that weren't at least cautiously revisionist anymore; if you still wanted to see a traditional western, Bonanza was on TV until 1973. With Rydell as director, The Cowboys was at least half a revisionist western, but thanks to Wayne, it still had one foot in the world of John Ford and backlot western main street sets.

It would take Wayne's death, just five years later, for westerns to float free of their historical moorings and cease to exist as a freestanding genre altogether. But to make that happen, you had to kill John Wayne.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.