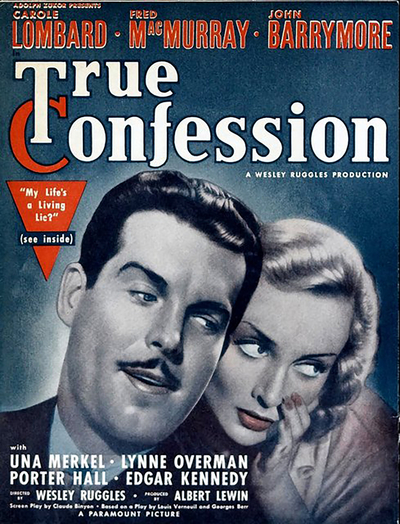

Of all the actresses who starred in screwball comedies – a genre that favoured its female leads above everyone else – Carole Lombard is the exemplar, suited to the peculiar demands of the films even more than Loy, Colbert, Davies, Arthur, Hepburn, Russell, Dunne, Rogers or Stanwyck. This is never more true than in True Confession, a 1937 picture where Lombard's Helen, an aspiring writer and compulsive liar, distinguishes herself by being just that little bit dafter than anyone else onscreen.

The film begins on the stairs of a New York City walkup apartment building, where Lombard's Helen mutters to herself as she climbs each flight, rushing to get to the phone with an important message for her husband Ken (Fred MacMurray). Ken is a lawyer whose practice is failing because he won't represent guilty clients, and Helen thinks he can get them out of a bind by defending a relative of their butcher, accused of stealing a truckload of hams.

She calls Ken at his office, tells him that she's sent the man over to him, and begs him to take on the job if only so they can take care of the debt they owe the butcher. The man arrives, shifty and collarless, assures Ken that he's innocent, then says he'll have to wait to get paid his hundred dollar fee until he can fence the hams. Welcome to screwball world.

Somehow a man who values honesty above all else has managed to marry a woman who can't get through an hour without a juicy lie, the more improbable the better. (Lombard telegraphs the arrival of each new fib by ostentatiously sticking her tongue into her cheek.) It's also unlikely that a lawyer will thrive without defending the guilty or prosecuting the innocent, but that's one of the building blocks of the screwball comedy universe – a refreshing appreciation of the unfairness and even absurdity of life, and the dimness, incompetence, hypocrisy and outright larceny motivating the people populating screwball world.

Helen's lack of success as a writer is explained harshly but honestly by her best friend Daisy (the criminally underrated Una Merkel) as having a lot to do with her stories being lousy because her characters are nuts. In screwball world you aren't expected to admire or respect the protagonists as much as find them amusing and appealing, even familiar if you have that much self-knowledge.

In Romantic Comedy in Hollywood: From Lubitsch to Sturges, James Harvey describes Lombard's performance in Nothing Sacred, made just before True Confession, as a woman who becomes a celebrity when everyone thinks she's dying:

"She is not one of those heroines, like Garbo's Ninotchka or Dunne's Theodora, who transform themselves. She may, however, attempt to transform her circumstances – usually by taking some desperate chance, attempting some monstrous deception or imposture. But she remains herself through it all, cursed with consciousness, mired in the intractable."

Ken has a lot of principles, and one of them is that his wife shouldn't work to help support them. So of course Helen secretly takes a job as personal secretary – despite not knowing how to take dictation or type at speed – to an old family friend, a rich broker willing to pay far too much for far too little work. Inevitably he ends up chasing Helen around the office couch in his massive townhouse and she bolts, leaving behind her hat, coat and purse. She makes Daisy accompany her back to the house to retrieve her things, only to find that the broker has been shot – twice, and in the face! – and that she's now the prime suspect.

There's an interrogation at the police station where the lead detective Darsey (Edgar Kennedy, playing neither his first nor his last comic flatfoot) tries to extract a confession from Helen by concocting increasingly elaborate murder scenarios. His obvious enthusiasm for each story is avidly shared by Helen, who's so swept up in the sweat-soaked detective's narrative creativity that she's willing to confess to anything as long as he's in the throes of inspiration.

It turns out that Darsey didn't have to bother coming up with murder scenes when they discover a gun in a dresser drawer in Helen and Ken's apartment with two empty chambers. (Helen tells Daisy that she fired the weapon during a weekend in the country while researching a murder mystery she was writing.) Convinced that it will be easier for her to plead guilty defending her virtue than proclaiming her innocence, and excited to see her husband fighting for her life in court, Helen obliges Ken to defend someone he suspects might be guilty while perjuring herself.

Why, you wonder, does Ken compromise his values and endure his wife's serial fabrications and the awful situations they force upon him? Well, as with almost every screwball comedy it's the heroine at the centre and the admixture of charm, wit, smarts and beauty they embody. Harvey talks about "the way she sits next to her husband, leaning into his back, looking at him anxiously as he struggles with himself, his face turned away from her. Like two shipwrecked people, in their own living room."

"Their physical attraction – so evident in this and other scenes in the film, none of them technically love scenes – is something she accepts better than he does. He is still fighting her: talking about going to China or some comparable distance, when everything in the image suggests he can hardly get off the couch they are sharing. A scrupulously honest (and consequently poor) young lawyer, unimaginative, humorless, and likeable, married to a compulsive liar – 'I'm living in a nightmare,' he says, as she watches him tensely from behind. No matter what he does or threatens to do, no matter what she herself promises, he is always catching her in another lie."

With the trial now imminent, the film introduces a wild card to the story – John Barrymore as Charley Jasper, just three years after he had co-starred with Lombard (his name above hers on the posters) in Howard Hawks' classic screwball Twentieth Century. By now reduced to playing bibulous self-parodies, his Jasper is a self-styled master criminologist who spends much of the film leaning on the bar in a basement dive, bantering with the barkeep who holds him in bemused contempt.

Jasper is a pompous lunatic who haunts the courts during murder trials, and he guesses that Helen is innocent but that she's "going to fry." As if trying to defend his square footage against Lombard, Barrymore shamelessly chews up the screen, often breaking the fourth wall to mug directly at the camera. (More probably reading his lines there, as the actor had by that point given up memorizing scripts.) He becomes a regular at Helen's trial, squeezing into a bench next to Daisy and blowing up rubber balloons, a bit of business that has him let the air out with a long, farting wheeze at inopportune moments.

True Confession was directed by Wesley Ruggles, a veteran director whose career went back to the silent era. He had first worked with Lombard on the pre-code screwball No Man of Her Own in 1932, the film that teamed her for the only time with future husband Clark Gable – one of Hollywood's great romances, even it only lasted for three years before Lombard's death in a tragic 1942 plane crash.

They famously didn't take to each other during filming, though onscreen there was plenty of chemistry, including a scene where Gable admires Lombard's legs while she shelves books in a library. The film is remembered as one of the reasons why the Production Code was rushed into effect a year later.

Ruggles would be troubled by the censors overseeing the Code again during True Confession, when they objected to Helen's perjury as a "travesty on the courts and the administration of justice." The courtroom scenes in the film are so farcical that Barrymore's rubber balloon is a rare moment of gravitas. Witnesses are comically inept – the coroner's testimony, a litany of sleepy malaprops, is a highlight – and the prosecutor (Porter Hall) is a classic little man aspiring to bully status.

Ken and Helen's reenactment of the "murder" is particularly absurd, and the jury is apparently baffled by the judge's instructions, but they acquit Helen nonetheless, disappointing Jasper but turning Ken into a star lawyer and Helen into a bestselling writer when she authors an account of the trial.

When we see the couple next they've moved from their walkup into a grand lakeside home. Ken is still troubled by his wife's chronic fabrications and his violation of his principles, while Helen seems quite happy to have escaped the consequences of her lies. Into this troubled paradise walks Jasper – or rows, however, as the only way to their house is over the water – who produces the murdered broker's wallet, which he offers to sell to Ken and Helen for the sum of $30,000 and a promise that he'll disappear without confessing to the killing, which would ruin his newfound legal reputation and expose her as a perjurer.

True Confession's slap-happy atmosphere can feel a bit relentless; I couldn't help but compare it to Bringing Up Baby, a film I wasn't able to finish watching for years thanks to Katharine Hepburn's Susan, whose madcap interference into Cary Grant's life actually feels malicious, even psychotic.

In spite of this, screwball world looks like a fun place to live, even if it's likely to make you a bit screwy yourself. On reflection it's really just a less sinister version of the place most of us live in already; if the last two years have done nothing else, they've made it clear that we live in a world run by the feckless, dim, hypocritical, incompetent and larcenous. Our tragedy is that there are fewer and fewer nutty dames like Carole Lombard, built to rebel against the dopes and the dullards all around her – as Harvey describes her "deep impatience with everydayness and with the ordinary limits of ordinary life. She is consumed by this recklessness – isolated by it and cut off from almost everyone else on the screen."

"But it's the recklessness and impatience that connect her to us – even powerfully. So that Lombard's solipsism – and is the special screwball twist – is not just a joke, as the Lubitsch's heroine is more or less, but a kind of triumph."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.