Anyone who grew up in the Seventies will remember "Surrender," a hit for the band Cheap Trick in the summer of 1978, when the end of the decade was finally in sight and its peculiar tenor and tone could be tentatively analyzed. The song, written by guitarist Rick Nielsen, was about an American family – Baby Boomer children troubled by a clash of values with their Greatest Generation parents, and their gritty real-life experience of life earned during World War Two.

The narrator – embodied by singer Robin Zander, one of the group's matching pair of heartthrobs – tells an erstwhile girlfriend that his mother had warned him about "girls like you," mostly because "you'll never know what you'll catch." This is followed by a verse explaining that Mom knew her stuff – stuff meaning venereal disease – having "served in the WACs in the Philippines." Zander speculates on the reputation of female GIs as "old maids," but is assured by old Dad that "Mommy isn't one of those," whatever that's supposed to mean.

This awkward little scene – hard not to perceive as Nielsen's riposte to wholesome sitcom families like the Nelsons, the Cleavers, the Stones and the Thomases – gives way to the anthemic chorus, with its first lines:

Mommy's all right, Daddy's all right

They just seem a little weird

Look, I know it's not "The Shadow of Your Smile," but that was not a gift my generation was ever going to receive, OK?

If Boomer kids were mystified by their GI Generation parents, then Generation X – my cohort, birthed in the Boomers' shadow, sometimes (like me) to Boomer parents – was baffled by them all. We spent the decade between the Jackson 5's first number one hit and the introduction of the Rubik's Cube trying to make sense of everyone, from our older siblings to our parents, teachers and grandparents, none of whom seemed to have absorbed the appealing message about stability and gentle authority in those old black and white shows that were still in syndication, and played in the fallow trough of afterschool TV programming between the afternoon soaps and game shows and the six o'clock news.

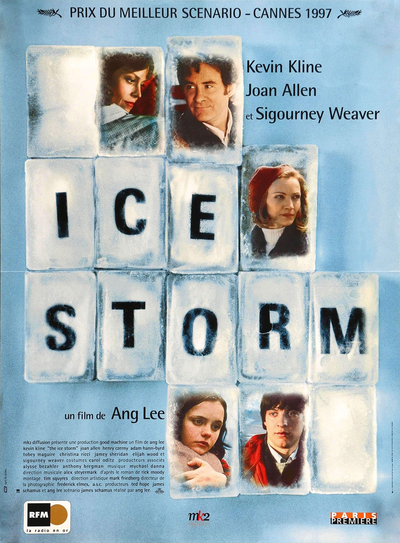

Movies had tried to tell the story of that strange decade before The Ice Storm was released in 1997, but none of them seemed to nail it so sharply, mostly because few of them realized that the best vantage point to take was that of the kids. Cheap Trick beat them to it twenty years earlier, and for that reason I've always regarded The Ice Storm as a movie version of "Surrender" as much as an adaptation of Rick Moody's 1994 novel of the same name.

We assume that the protagonist of the story will be Tobey Maguire's Paul Hood, who we meet on the Penn Central commuter train from Grand Central to New Canaan, Connecticut late one night while it's stranded by a power outage due to the film's titular weather event. (The train still runs as a branch of the New Haven Line on the Metro-North Railroad, and still terminates in New Canaan.) It's autumn of 1973, Thanksgiving weekend; the Watergate hearings are in their seventh month, Skylab 4 has been in orbit for just over a week, Richard Nixon has just told reporters in Florida that he's not a crook, and A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving debuted on CBS three days earlier.

Paul is sixteen, smart but hapless, attending a good co-ed private school and worried his parents are on their way to divorce court. It's a reasonable concern, since his dad Ben (Kevin Kline) is sleeping with Janey Carver (Sigourney Weaver), a neighbour just down the street in their sylvan neighbourhood in one of New York City's affluent bedroom communities. (A million US dollars will buy you a house like the Hoods' in New Canaan today – which is a lot more house than the same money will get you in my hometown, Toronto.)

His little sister Wendy (Christina Ricci), flush with the sudden power awarded to teenage girls in the scorched earth aftermath of the sexual revolution, is playing a game of sexual chicken with the Carver boys, Mikey (Elijah Wood) and Sandy (Adam Hann-Byrd), both of whom would probably be diagnosed somewhere on the autism scale today. At dinner parties the adults chat explicitly about the affairs and breakups of friends and neighbours while the kids drain the dregs of their cocktails and wine glasses in the kitchen.

The inflation rate in 1973 was 6.22%, the same as it is today, but a 1973 dollar is worth over six times more. The film painstakingly recreates the look and feel of the time, with the chatter from the TV briefly referencing the first oil crisis, which began a month previous. In some ways the setting of The Ice Storm feels more relevant now than it did in 1997, though the Woods and the Carvers aren't troubled by any apparent guilt about their white privilege, and Ben actually shouts down Wendy when she sullenly ad libs grace at Thanksgiving dinner, talking about stuffing their faces and napalmed children and "killing the Indians."

Ben Hood works unhappily on Wall Street, while it's never really certain what Jim Carver (Jamey Sheridan) does, except that it has something to do with silicon chips and Styrofoam packing pills, pays for their white modernist box in the woods, and requires him to be away long enough for Janey to schedule trysts with Ben in their guest room in the middle of the day. Probably an Aspergers case himself, Jim is the only adult in the movie who seems to actually enjoy what he does for a living, though he's unable to muster the (minimal and mostly unrewarded) effort to communicate with his kids.

Ang Lee's previous film was a period movie, an adaptation of Jane Austen's Sense and Sensibility, and he approached The Ice Storm as a period picture as well – a fact that slapped me in the face the moment the camera lingered on Christina Ricci's toe socks, the likes of which I hadn't seen since grade six.

If 1973 looks like a distant era today, it was already receding into the past when Rick Moody wrote his book. Moody was at pains to evoke the era for those too young to have lived through it – or who had made a diligent effort to forget.

"The bright hues of the sixties had vanished from contemporary interior design," he begins one chapter. "Where the wives of southern Connecticut in the past might have embraced – carefully, hesitantly – gaudy neons and Day-Glos, they had by 1973 settled into milder pastels and earth tones...The decorator fabrics themselves were more durable than in the past. Synthetics and cotton/poly blends dominated. Plastics had also penetrated far into the home. Coffee tables, modular furniture, kitchenware, and electrical appliances – all could now be fashioned from plastic."

Three paragraphs into his book Moody makes sure he draws a firm technological, social and cultural line between the story's setting and the very different world of the first Clinton presidential term:

No answering machines. And no call waiting. No Caller I.D. No compact disc recorders or laser discs or holography or cable television or MTV. No multiplex cinemas or word processors or laser printer or modems. No virtual reality. No grand unified theory or Frequent Flyer mileage or fuel injection systems or turbo or premenstrual syndrome or rehabilitation centers or Adult Children of Alcoholics. No codependency. No punk rock, or postpunk, or hardcore, or grunge. No hip-hop. No Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome or Human Immunodeficiency Virus or mysterious AIDS-like illnesses. No computer viruses. No cloning or genetic engineering or biospheres or full-color photocopying or desktop copying and especially no facsimile transmission. No perestroika. No Tiananmen Square.

The eagle-eyed might be able to spot a few inaccuracies in Moody's list but the point remains – 1973 was not 1994, and 1994 now looks as far away today as 1973 did then. We all live in some future period movie.

If the kids are confused by the adults, it's because not even the adults seem able to explain their motivations. It's hard to understand why Ben and Janey are having an affair because they don't seem to like each other very much; Weaver's Janey seems done with everyone, her expressions hovering between boredom, impatience and rage. Ben's idea of post-coital chat revolves around his golf game and an office rivalry, which Janey shuts down abruptly.

"Ben. You're boring me," Weaver intones between drags on her cigarette. "I have a husband. I don't particularly feel the need for another.

"You have a point there," Kline's Ben replies, perhaps aware that all the golf talk was boring, even to him. "We're having an affair," he states, as if he needs to remind himself.

When she discovers Wendy playing "I'll show you mine if you show me yours" in the bathroom with her youngest son, Janey's fury quickly dissipates into a desperate but incoherent attempt to warn the young girl, citing Margaret Mead and Samoan natives and telling her that "in adolescence our bodies tend to betray us."

Midway through feminism's second wave there still doesn't seem to be anything fulfilling on offer for women like Janey, and for Ben's wife Elena (Joan Allen) it's even worse. Janey is still an object of lust for the men of New Canaan, but Elena is one of those women who fears she's becoming invisible, even before she knows about her husband's affair.

Browsing a book table outside the town's public library, Elena does catch the eye of one man – Philip (Michael Cumpsty), the long-haired, turtlenecked pastor of some unconventional new age congregation in the town, who does a poor job of disguising his earthly longing behind spiritual banter. She's looking for a way out of the conversation when Wendy glides past on her bike, triggering a surge of nostalgia and regret in her mother, whose problem isn't that she's having a hard time being a woman as much as she longs to be a girl.

Lee sets up deliberate parallels between the mother and her daughter. After watching Wendy ride down the town's main street, Elena unearths her own old bike from the garage and takes to the roads, eager to recapture the freedom she thought she saw in the girl. In an earlier scene we saw Wendy shoplift a package of Devil Dogs from the local pharmacy, brazening past the older woman who saw her with a cool, confrontational stare. When Elena pockets a lipstick from the same shop she's caught, a humiliation that sours her mood and sets the tone for the tragic climax on the night of the ice storm.

Which brings us to the film's most famous scene – the "key party" that brings all of the tension and simmering dread to its inevitable climax. When my dear friend Kathy Shaidle wrote about The Ice Storm nearly a decade ago (after borrowing my DVD of the film) she was skeptical about it all, and wrote that "it's possible these suburban wife swapping 'affairs' are an urban legend, like 'rainbow parties' or 'bra burning,' which only became 'real' after someone invented them and spawned a moral panic."

There still doesn't seem to be a consensus that key parties were really a thing, and no less than a San Francisco Weekly story from 2018 concludes that persistent references to them are "based on secondhand stories — which determines whether you believe key parties happened. Do you count the retelling of other people's 1960s oral histories as proof? Then sure, somebody said that somebody said key parties happened."

"But a rigorous, fact-based analysis shows little proof, and relegates key party rumors to the level of urban legends like gerbilling, rainbow parties, and 'Hot Karls.' You can Google these terms if you must. But we don't recommend you do so from your workplace computer, or HR might get a little keyed up."

After Ben inadvertently confirms that he's having an affair with Janey, the Hoods arrive at their social circle's big annual Thanksgiving affair and discover that a key party is the bonus feature. Furious at her husband, Elena tosses their car keys to the host (Allison Janney) and tries to avoid Ben for the rest of the evening. The first person she meets is Pastor Philip, who tells her that "sometimes the shepherd needs the company of the sheep."

"I'm going to try hard not to understand the implications of that," Elena replies coldly. The reverend beats a chastened retreat, but not before fishing his car keys from the bowl.

Everything that follows is mortifying – a dismal scene of deliberate adult misbehavior that the kids today would call "cringe." At the end of the evening the only people left by the bowl are Jim and Elena, who end up in his car, fumbling at each other like horny kids, with much the same brisk outcome.

"That was awful. Really awful. I'm so sorry," Jim pleads.

But it isn't the worst sex in the movie, which actually has no other kind. That prize goes to an earlier scene between Wendy and Mikey in the Carvers' basement; obsessed with Watergate, the girl finds a rubber Nixon mask, pulls it over her head, and tells the boy that she'll "touch it" but she won't take off her pants. As they dry hump on the sectional, it's plain that there's no way he'll ever be able to untangle that Nixon mask from his earliest sexual memories. Cruelly, it makes Mikey's eventual, tragic fate almost a blessing.

The final verse of "Surrender" has Zander wake up to discover Mom and Dad "rolling on the couch / Rolling numbers, rock and rolling / Got my KISS records out." At the time this last image was supposed to be triumphant, but I was never able to shake a reaction that it was, profoundly and undeniably, cringe.

In the end I think it's hard to make a convincing case that "Mommy's all right, Daddy's all right" and, really, they're more than just a little bit weird, but back in the Seventies that was a relative term. On my street in west end working class Toronto the moms and dads didn't have a clue what was going on, and our older siblings were rebelling furiously despite lacking the safety net that the children of New Canaan could rely on. I never heard about key parties, but a guy down the street who worked at the airport – the father of one of my sister's friends – would invite other dads down to his basement to watch porn loops confiscated by Canada Customs.

They key to Rick Nielsen's fable about surviving the Seventies is actually in the last half of the chorus, when Zander sings:

Surrender, surrender

But don't give yourself away

The last shot of The Ice Storm is Tobey Maguire's Paul – who didn't turn out to be the protagonist of the story – looking baffled in the back of the family car at the train station while his father weeps into the steering wheel. He's grateful to be home but has no idea yet what happened in his absence. The repercussions from the night before are going to be severe, and since escape isn't really an option, Paul's best course of action is to surrender – to being part of his family, to his advantages as a child of privilege, and to the weird gifts that living through the Seventies gave us.

Paul and Wendy and Mikey and Sandy are demographically on the tail end of the Baby Boom, but I can't help but identify them with Generation X, since none of us got to really enjoy the postwar boom, and our earliest memories are of the chaos and decline that came after that boom went bust. What we learned was to hold the mainstream at arm's length and not give ourselves away – a survival tactic in which my peers take a perverse kind of pride. It's certainly made surviving the last couple of years possible, but don't ask us for any solutions, since we barely know how we made it out of the Seventies.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.