Back when everybody was desperate for an answer to why and how a small group of terrorists could hijack four planes and commit the worst act of terror ever on U.S. soil, newspaper columnists and serious people writing for reputable magazines began touting The Secret Agent. The 1907 novel by Joseph Conrad is a story – mostly grim but, occasionally, aridly comic – about a group of ineffectual anarchists and an agent provocateur from a foreign country who manage to detonate a bomb in the Greenwich Observatory, and while it's a characteristically excellent tale by Conrad, it had few practical insights into the minds of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed or Mohammed Atta, and we stopped hearing about it after a few weeks.

I really hope at least a few of the people who bought it in those feverish months in late 2001 actually read the book, if only to distract themselves from the endlessly recycled cable news and the general feeling of confusion and despair.

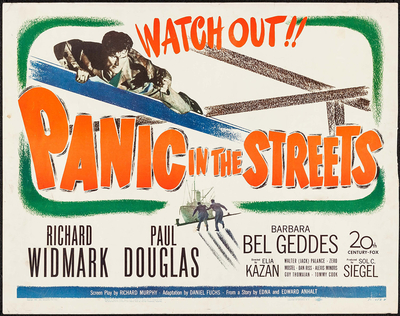

For much the same reasons, the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic last year saw reputable journals and websites recommending Albert Camus' 1947 novel The Plague, often alongside a 1950 film noir by Elia Kazan, Panic in the Streets, as potential keys to help serious people interpret the unfolding crisis.

The credits roll over a long shot driving down Bourbon Street in New Orleans at night. Alfred Newman's score is jazzy and blaring – exactly what you'd expect for the genre and the location. This is the seedy but vital Bourbon Street where you'd once find both locals and tourists. Today a native to New Orleans wouldn't be caught dead on a street full of souvenir "voodoo" shops and staggering bachelor and hen parties swigging their oversized plastic glasses of frozen daiquiris and hand grenades. For a postwar American audience it signals that we're in the wide open city, America's most exotic town, a port city full of the usual vices, and a few unique ones.

We get right down to business with the first scene – a poker game in an apartment above a club in an insalubrious dockside section of the French Quarter. A man begs that he's not feeling well, that he needs to take his winnings and go, which doesn't sit well with the men who brought him – his cousin Poldi (Guy Thomajan) and an abject fat man named Fitch (Zero Mostel) – or the man running the game: Blackie, the film's heavy, a small-time but dangerous gangster played by Jack Palance in his first screen role.

The sick man staggers away, pursued by the three hoods, down to the docks; we learned that he'd only just got off a boat that day, so perhaps this is the closest thing he has to home in the strange new city. It doesn't save him in any case – he wildly fends off Poldi and Fitch just long enough to get gunned down by Blackie, who collects his money and tells his henchmen to get rid of the body.

The unlucky stiff turns up the next morning in a tangle of debris by the Canal Street Pier – now long gone, along with much of New Orleans' old port and the warehouses that clustered where downtown met the Mississippi. A coroner at the city morgue is troubled by what he finds while fishing out the bullets. He calls in Lt. Commander Reed (Richard Widmark) of the U.S. Public Health Service, who confirms the worst – pneumonic plague, an equally deadly sibling of the bubonic type – and a forgettable John Doe suddenly becomes patient zero, the key to stopping an epidemic that could start overwhelming the city in forty-eight hours.

Reed barely manages to convince the mayor and his administration of the imminent crisis, and for his trouble he's paired with Captain Warren (Paul Douglas), a tough veteran NOPD detective with little patience for public servants playing Chicken Little. Later, Kazan would sum up this odd couple at the centre of his film: "The Doc was a New Dealer and the policeman a Republican. That was the way we thought, the remnants of my former political training: everybody representing some social political position."

Kazan was known as an actor's director, and he began his career in the coterie of New York theatre types who would create Method Acting – a more naturalistic style than the overt theatricality that ruled Broadway and, by extension, Hollywood since the advent of sound. There's not a lot of Method on view in Panic in the Streets – that would have to wait until his next film, A Streetcar Named Desire, and the explosive launch of Marlon Brando's onscreen career.

What there is a lot of is faces. Kazan was painstaking in his casting, and the chance to shoot on location in New Orleans freed him from the restraints of the studio and the backlot, and he drew on a roster of character actors as well as untrained locals to fill the frame. The morgue scene is startling, nearly a documentary with its offhanded dialogue, the actors bantering so casually that it feels unscripted.

Most striking of all, though, is a scene in a dingy café next to the National Maritime Union hiring hall, where Reed has gone to try and find any merchant seaman who might have seen the dead man arriving in the port. Waiting for someone to take his $50 bribe for information, the camera dollies down the crowded bar where a gallery of faces – sad sacks and hard cases and life's losers – huddle against each other to pool the warmth of their coffees.

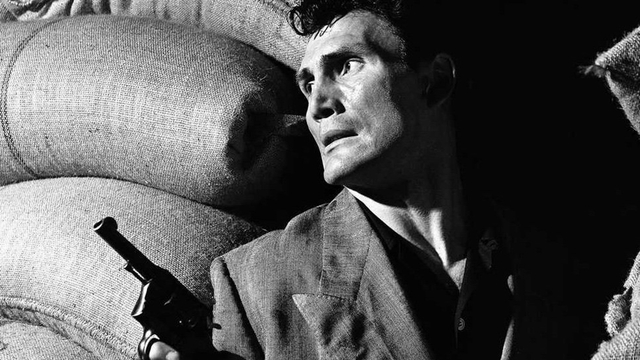

The contrast between Douglas and Widmark in startling; the cop has a huge head with appropriately generous features, filling every inch of his face, while Widmark's small round head crowds his features tightly in its centre. Widmark didn't get a lot of heroic roles or romantic leads early in his career; there's still debate about whether casting him as Doris Day's husband in the infidelity comedy The Tunnel of Love (1958) was what sunk that film.

Playing gunsels and heavies, Widmark ranged from squirrelly to psycho, and even as the uniformed doctor in Kazan's film he's more peevish than stoic; you can't help but wonder how he would have been played by, say, Gregory Peck, the star of Gentleman's Agreement, the film that won Kazan his first Oscar three years earlier.

Palance's Blackie has the hardest face of them all, with cheekbones and a brow that could have been hewn from granite, an unmovable, unforgiving façade that barely hints at humanity – a real Easter Island moʻai of a mug. It's hard to square him with the remarkably expressive actor he became later in his career.

Faced with a two day deadline, the cop is skeptical that they're going to find three crooks in a city full of low-lifes without catching a lucky break, but somewhere along the way the flatfoot is won over by the sawbone's urgency and decides to toss a hack who's sniffed out the story into jail without charges – a move that even his underlings think will get him tossed off the force.

It's the film's big ethical turning point. It happens after the virus takes its first victim after the luckless gambler – the wife of the owner of a Greek restaurant who served the dead man after he snuck off the tramp steamer where he was a stowaway. She'd convinced her husband not to talk to the cop and the doc when they came around asking questions, which is just one of the obstacles the cop – with his street-level knowledge of human nature – knew would get in the way of tracking down potential carriers.

The other is that once news of the plague breaks, the city will empty out and every potentially infected person will be on the road to somewhere else, which is the doc's biggest fear. On the other hand, if people knew what they were facing, the Greek's wife might have gone to a doctor instead of thinking she just had a bad cold. The authorities – the doctor most of all, and everyone else on the hunt for the infected crooks – can't say with real certainty that they know how to handle the outbreak beyond tracking down the first infections.

"You don't know," the reporter accuses them. "And because you don't know you don't want anyone else to know."

Political pressure on the mayor gets the reporter released, and the imminent publication of the story in the morning edition means that the doc and the cop now only have four hours before the titular panic in the streets breaks out.

The authorities claim they're trying to protect the community, which prompts a passionate speech from Widmark, who tells the mayor that community is irrelevant, a medieval relic – that anyone could be in another country "in 10 hours" nowadays. (A number that's been reduced by at least half today.)

It's easy to see why Panic in the Streets – which was originally titled Point of Entry and then Outbreak – looked relevant to anyone trying to find something insightful to say about the pandemic last year. Writing about the film in the Paris Review in March of 2020, movie critic J. Hoberman called Douglas' cop "Trumpy," pointed out that Kazan's film had the virus spread by "foreigners and criminals," and went on a tangent stressing parallels between the plague and the rhetoric used to warn against infiltration of America by communism, citing one of the film's bad reviews when it was released – in the Daily Worker.

"The reviewer," Hoberman notes with approval, "could hardly miss the movie's coincidental illustration of Attorney General J. Howard McGrath's recent warning that in America Communists were 'everywhere—in factories, offices, butcher stores, on street corners, in private businesses. And each carries in himself the germ of death for society.'"

It would actually be two more years before Kazan was called in front of HUAC, where he named names (but only after declining to do so in a private session with the committee – news of which was apparently leaked to the press, prompting the head of 20th Century Fox to threaten the director that his silence would end his career.) Still, Hoberman uses this as a lens to retroactively judge Kazan's work, before going on to speculate that Donald Trump would use the pandemic to preempt the year's coming elections. (No points for Mr. Hoberman's oracular abilities there, I'm afraid.)

Kazan's testimony would loom over the rest of his career; at a press conference in France in 1982 Orson Welles called him a traitor. (Welles, however, committed the all-too-common error of making Joseph McCarthy a member of HUAC; the senator wouldn't begin his own crusade against communists in the U.S. government until a year after Kazan's testimony.)

He was still contentious in Hollywood when the director was given an honourary Oscar in 1999, twenty-three years after he'd made his last film, in front of an audience of celebrities that either stood and clapped enthusiastically (Warren Beatty and Meryl Streep), sat in their seats and politely clapped (Steven Spielberg and Jim Carrey) or glared sullenly at the stage (Ed Harris, Amy Madigan and Nick Nolte). In 2018 actor Richard Dreyfuss gave a podcast interview where he called Kazan a "serial betrayer."

It would take work to deny that Kazan was an important filmmaker – perhaps the most important one of all in the '50s, when his work pointed the way to the post-studio future of American movies. But his HUAC testimony has permanently coloured his reputation for posterity, pitting an unalloyed virtue (personal loyalty) against opposition to an undeniable evil (totalitarian communism.) It's difficult to find a reasonable take on Kazan even today, though this YouTube essay makes a fair attempt at this thankless task.

Writing about the movie from a very different political viewpoint for the Daily Signal at the same time as Hoberman, Hans von Spakovsky (real name, apparently) asserts that:

In the real world, China's totalitarian government unwittingly copied what happened in the movie and initially tried to suppress information about the virus and its spread, which resulted in it migrating to all parts of the world.

As Washington Post columnist Marc Thiessen has pointed out, totalitarian regimes lie to themselves and then lie to the world to cover up the truth, even when millions of lives are at stake.

Public health authorities know that transparency and information is the best way to beat a pandemic.

Over a year and a half later, it's a stretch to say that that transparency and information have beaten this pandemic, which doesn't seem to have an end in sight as I write this. The former has been intermittent at best, and the latter has only added to growing confusion about what's actually happening. There has been, in reality, too much information in circulation, resulting in either a distrust of the numbers provided or increasingly authoritarian commands to trust what we're told to do no matter how implausible it seems or how it affects our lives.

It doesn't help that, seventy years on, the world of Panic in the Streets is markedly different from our own, and not just because travel is even faster and easier. Try to imagine the same movie if every bystander to the constant and public arguments between the cop, the doctor, the mayor and the journalist had a smart phone – and accounts on Twitter, Instagram, Gab, Telegram and Facebook.

In Kazan's movie there's already a vaccine for the disease, and Widmark's Reed is constantly pulling out a syringe to inoculate everyone he meets – and even then, despite the authority of his uniform in postwar America and the threat of a known, deadly plague, many characters are reluctant to roll up their sleeves, including the cop.

I couldn't help but notice that the only time a face mask appears is nearly an hour into the film, when Reed and his assistant attend to the corpse of the restaurant owner's wife in the confines of their tiny apartment's bedroom. I also found myself cringing during the scene where Blackie and Fitch try to get an obviously dying Poldi to tell them where he's hidden the goods they suspect Poldi's dead cousin had smuggled into the country – the reason they assume the cops are looking for them.

While an obviously sweating Fitch hovers over Poldi's sickbed, Palance's Blackie cradles the dying man's head, mopping his brow and gripping him by his cheeks, his face intimately close to the sweating, delirious Poldi as he tries to cajole a confession from him. Perhaps it's the result of a year and a half of masking and social distancing, shots and tests and unrelenting messaging that not just strangers and neighbours but friends and family were all potential sources of infection, but the scene had more tension and suspense than the one that follows, with police chasing the crooks through New Orleans' docks.

Ultimately Panic in the Streets doesn't really explain much about the Covid pandemic as it was understood when it was still considered a risk that could be defeated by staying home for two weeks – after all, Widmark and Douglas beat it in just two days. Camus' The Plague, on the other hand, might end up being more insightful and evocative. There's that sense of being united, even against our will, that characterized the early weeks of lockdown, as described by Camus: "Once the town gates were shut, every one of us realized that all [were] in the same boat... No longer were there individual destinies; only a collective destiny."

And then, of course, there's the subsequent sense of helplessness in the face of the growing exercise of arbitrary authority, which will inevitably lead to confusion, despair and anger:

They had been sentenced, for an unknown crime, to an indeterminate period of punishment.

I can't wait to see the movies that might one day be set during the Great Covid Pandemic, if only so I can complain about what they get wrong, but mostly because their existence will (hopefully) mean that this whole, awful episode will have (finally) become history.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.