During its last golden age, there was an unwritten law that westerns needed not just a rousing score but a song or two. Think of Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson singing about "my rifle, pony and me" in Rio Bravo, or Tex Ritter's elegiac "do not forsake me oh my darling" in High Noon. Technically you could include Gene Pitney's hit "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance," even though the song was intended to be the theme to the 1962 John Ford film but got dropped from the soundtrack halfway through the recording session – at least according to Pitney.

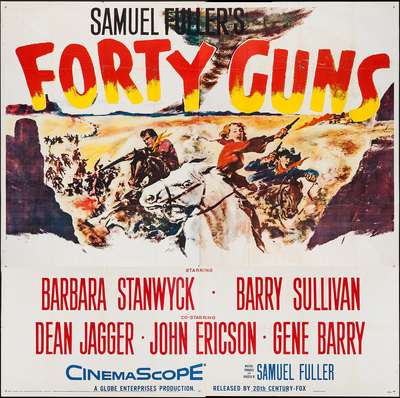

There are not one but two songs in director Samuel Fuller's 1957 western Forty Guns, the first of which is heard in the third scene, sung by Jidge Carroll as Barney, the owner of the open air bathhouse in Tombstone where the Bonnell brothers have just arrived on their dusty buckboard.

As he carries buckets up a hill to the yard full of washtubs where the brothers are soaking away the dirt of the trail, Barney sings about an imposing female, a "high riding woman - with a whip." It's inspired, he tells us, by Jessica Drummond (Barbara Stanwyck), the boss of Cochise County, who the Bonnells had briefly met in the first scene of the movie, thundering down the trail at them on a white horse at the head of two columns of cowboys on black steeds – the forty gunmen she employs to run the territory.

Jack "Jidge" Carroll was born Vincenzo Riccio in Belleville, New Jersey; he sang alongside Doris Day with Les Brown and His Band of Renown and served in the army before he started a career as a nightclub singer after the war, with a sideline recording demos for big name singers like Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley – a gig he kept at until his 80s. He had a decent career on television and in commercials, but his movie career didn't go much beyond the role in Forty Guns.

It seems like half the men in Tombstone are in love with Jessica Drummond, including Logan (Dean Jagger, best remembered as the retired general/failing innkeeper in White Christmas), the sheriff that Jessica keeps on her payroll. But we don't meet her again for a while; the movie still has to introduce us to Griff Bonnell (Barry Sullivan) and his brothers Wes (Gene Barry) and Chico (Robert Dix).

When Sam Fuller wrote his original script for Darryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century Fox several years earlier, the Bonnells were the Earp brothers, with Griff as Wyatt – the legendary gunman trying to leave behind his reputation as a hired killer. He's serving arrest warrants for the federal government now, and he's in Tombstone to bring in one of Jessica's "dragoons" for robbing a mail coach.

Wes is his sidekick and second gun, and Chico the kid brother about to be shipped off to the family farm in California. Good-humoured and even a bit maternal, Wes falls for Louvenia (Eve Brent), the daughter of the local gunsmith, who he courts with a flurry of firearm metaphors. Chico doesn't see himself as a farmer, and wants Griff to let him become his second gun when Wes decides to stick around, marry Louvenia and become Tombstone's marshal.

But Chico isn't the only younger brother causing trouble for their sibling; Jessica's kid brother Brockie (John Ericson) is a spoiled monster who shoots the local marshal before leading a bunch of the dragoons on a drunken rampage through the town. Griff is forced to step in, and when he does, Fuller stages a showdown that lays out the gunman's legendary power.

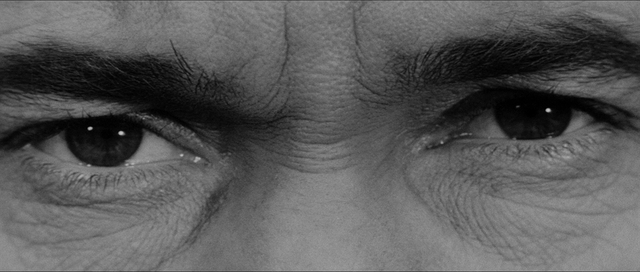

Walking towards Brockie up the dusty main street of Fox's backlot western town – unlike most backlot western sets, Fox built theirs on a series of steep hills – Griff simply fixes his gaze on the staggering bully; the camera cuts between Brockie and Griff, getting closer every time, focusing on Griff's relentless tread and then just his eyes, filling the Cinemascope screen with them. We lose track of just how much distance is between the two men until Griff is literally on top of Brockie, pulling the gun from his waistband – before the apparently mesmerized younger man can react – and pistol-whipping him to the ground, then dragging his body into a wheelbarrow that he pushes back down the street to the jailhouse.

This draws Jessica back into town, where she collects Brockie and brushes past the ad hoc trial, getting back on her horse and riding away without paying the nominal fine imposed by the court. We learn how Jessica has gone from cattle baron(ness) to boss through shrewd patronage and outright bribes, taking kickbacks on taxes that the government would otherwise have been unable to collect at all. She's a master at imposing order on a lawless frontier, but she knows that time is coming to an end and, even worse, she's surrounded herself with idiots and psychos like Logan and her little brother.

It's a departure from the usual "man's world" of the western (unless you ignore films like Johnny Guitar or The Furies or Destry Rides Again or Calamity Jane) and it might have been less probable if Stanwyck weren't there to sell it. (She'd already had practice with Anthony Mann's The Furies in 1950.) By western movie standards, Stanwyck's Jessica is more man than anyone else in Cochise County, sitting at the head of a long dining room table in her ranch mansion with her guests and all of her dragoons, a liege lord surrounded by her sworn knights.

Stanwyck was nearly fifty at the time of filming, and did all of her riding and stunts, including getting dragged by her horse through a tornado. It stands to reason that the only man up to Jessica's standards is Griff, and even though his presence in Tombstone is a threat to both her family and empire, the two begin a flirtation that becomes torrid.

Fuller's script is loaded with outrageous double entendres involving cattle and guns, and you wonder how most of them got past the film censors of the day. After dismissing her dragoons from the table, Jessica asks if she can see Griff's "trademark" – his gun.

"Can I feel it?" she demands.

"Uh-uh," Griff replies coolly. "It might go off in your face."

Indeed.

Suitably, their flirtation is consummated during that tornado, a twister that whips itself up out of nowhere while Jessica is giving Griff a tour of her ranch. Sam Fuller was a director who had a reputation for being a "primitive" – a word that became attached to him during the long, difficult stretches of his later career when he was working with ever smaller budgets, struggling to remain employed while critics were already reappraising his work and calling him an auteur.

With scenes like the tornado, and the black shadow of a cloud that crosses the vast landscape in the first shot of Forty Guns, it's hard to call what Fuller did primitive as much as primal; Fuller was better known for gritty, noir-like crime films and war movies than westerns, but he understood the potential of the genre to tell stories of outsized characters in extreme settings and rose to it with movies like I Shot Jesse James (1949), The Baron of Arizona (1950), Forty Guns and Run of the Arrow (1957).

Fuller was in his late 30s by the time he directed I Shot Jesse James, his first picture. He began his career as a crime reporter in New York City, working for the New York Evening Graphic, a tabloid with a very suitable name. While covering suicides, he had a habit of asking to keep the notes left behind, and ended up with an impressive collection of suicide notes. He enlisted in WWII as an infantryman, and ended up fighting in North Africa and Italy before landing in Normandy on D-Day. Fuller ended up with a reputation as a hypermasculine director of violent films, famous for firing a machine gun over actors' heads during battle scenes, and for movies that dropped plot points and threw red herrings everywhere in pursuit of thrills or indelible visuals.

Writing in The Films of Samuel Fuller: If You Die, I'll Kill You!, Lisa Dombrowski says that "Fuller's interest in creating intensified narrative situations in his screenplays often overrides the powerful influence of classical conventions.... It is telling that film trade publications described the vast majority of Fuller's pre-1970 pictures as melodramas, applying a longstanding definition that associated the term with thrilling, action-packed stories."

From the moment he arrives in town Griff knows that he has a target on his back, and survives several attempts on his life. In one ambush orchestrated by Logan, the sheriff, Griff is nearly taken out by Jessica's best marksman until Chico, who snuck off the stagecoach after his brothers saw him off for California, sneaks up behind the gunman and kills him – a "clean shot – right through the head" he brags to his brother, who's more appalled that the young man has taken to killing so enthusiastically. Griff acknowledges that his legend is based on the fact that he never misses, and he's come to consider it a curse.

"There's a new era coming up, Chico," Griff tells his brother. "My way of living is on the way out." It's the closing of the frontier – Frederick Jackson Turner's 1893 thesis on the end of an era of American history, by now an accepted part of western movie mythos.

"I'm a freak, Chico," Griff explains, bitterly. "I just don't want you to be one."

Later in the film Jessica echoes the idea: "You shot your way across the map. This is the last stop, Griff. The frontier is finished."

The last attempt on Griff's life is the most dramatic: at the wedding of Wes and Louvenia, Brockie kills the groom, missing Griff as he leans in to kiss the bride. Wes pins Louvenia to the ground with his dead weight as the bride – now a widow – screams his name over and over.

Fuller cuts to the funeral, a western cliché that the director sidesteps with an elegance that's hardly "primitive." Louvenia in her widow's weeds stands above the camera, which pans across the hearse and its horses to rest on Jidge Carroll's Barney, singing the movie's other song – "God Has His Arms Around Me." (The Sons of the Pioneers would record both of Forty Guns' songs for an RCA single that year.) The camera then pans back across the hearse and returns to Louvenia, now in a tighter shot. No dusty graveyard with its wooden crosses and skeletal trees, no mourners in their Sunday suits or preacher doing his mournful duty.

Shot in black and white, apparently to save money, Forty Guns is full of inky blacks and deep shadows more suitable to film noir than a western. It was shot by cinematographer Joseph Biroc, who also made Run of the Arrow in Technicolor with Fuller that same year, and also shot everything from It's A Wonderful Life to Red Planet Mars to Bwana Devil to Bye, Bye Birdie to The Killing of Sister George to Blazing Saddles to The Towering Inferno to Airplane!. His second last film was Hammett in 1982, working with German director and Fuller acolyte Wim Wenders.

By now the film has a grim purpose; Griff tracks Brockie down to the same adobe shack where he and Jessica had sheltered from the tornado, refraining from killing the young man on the spot. His sister promises to do everything she can to keep him from hanging, and in the process spends what's left of her fortune and burns her bridges with the authorities she once had in her pocket. Her forty guns abandon her.

When Jessica visits Brockie one last time before his appointment with the noose, the young man steals a deputy's gun and uses his sister as a human shield, daring Griff to come out and stop him. The final showdown is incredible: calmly responding to the killer's dare, Griff shoots through Jessica and wounds Brockie, then advances on the young man, by now on his knees, outraged that he's been shot. With the same relentless walk, Griff advances on Brockie, emptying his revolver into him without stopping. Stepping over the bodies, he intones "she'll live" before marching out of the frame.

Westerns are strange. Nobody can make the argument with a straight face that they work as real history. From their beginnings, when they were hectic B-pictures and corny serials to today, when every western is revisionist, the genre has been about meeting the expectations of audiences who never actually want to know what really happened.

But during their golden era – roughly from the early '40s to the early '60s – westerns were full of ambition and artifice, the specialty of directors obsessed with morality and honour, often featuring protagonists who'd either outgrown their legend as skilled killers or whose world had outgrown them, suddenly hemmed in by the politicians, bureaucracy and businessmen who had once lived thousands of miles away, sheltered in lawful cities by the ocean.

Fuller's original ending was bleak, omitting "she'll live" from the showdown. In the end he was forced to substitute a happier ending – one that, ultimately, makes us realize that Barney's smitten bardic tribute to Jessica at the beginning – the "high riding woman – with a whip" – gave away the whole plot in the first few minutes, since "a woman with a whip is only a woman after all."

Leaving Chico in charge as the new marshal, Griff gets back on his buckboard to head west, to California, ignoring his brother's plea to try to talk with Jessica before he goes. But Stanwyck's Jessica rises from her sickbed in the hotel dressed in bridal white and chases Griff up Tombstone's main street, and our last view of the couple is in the distance over the back of the buckboard, on their way to the Pacific.

You try to imagine a conversation they might have there, at some church social in Palo Alto: "So where did you two meet?" "Oh, back in Arizona." "He bankrupted me and killed my brother. But it was all for the best."

Which is why it's no good to think about westerns too much after the credits roll.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.