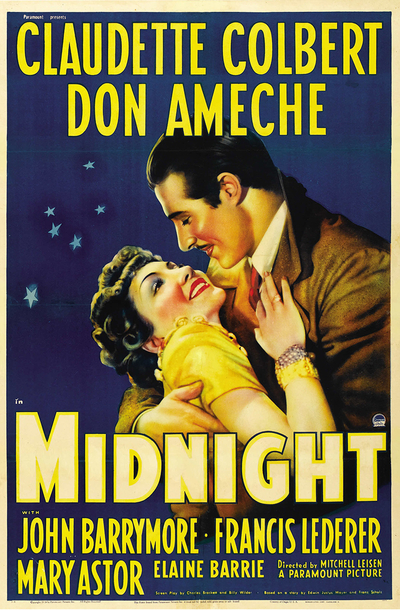

Midnight, a 1939 screwball comedy starring Claudette Colbert, is the second movie I've reviewed this year that starts with the heroine showing up at the start in a 3rd class train compartment to Paris. I don't even know if there's such a thing as a 3rd class compartment any more, but they were obviously once common enough that audiences understood immediately that they were shorthand for ambitious characters in straitened circumstances.

Colbert's Eve might only have twenty-five centimes (with a hole in it) to her name, but she's wearing a gold lamé dress. (If the actress had a signature colour, it was probably gold lamé.) The dress, as much as the woman in it, attracts a horde of taxicab drivers but Eve walks past all of them until she's caught out by a crack from Tibor Czerny (Don Ameche), a Hungarian who has found "peace of mind" during the interwar period by driving hack.

Hungarian violinists, Polish ex-cavalry officers, White Russian aristocrats and other refugees scattered by the Treaty of Versailles were another common movie cliché around this time, and they were often all over films made by two particular Hollywood refugees – Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder. Midnight is, in fact, directed by Mitchell Leisen from a script by Wilder and Charles Brackett, his regular scriptwriting partner for much of the '30s and '40s.

Eve makes Tibor a proposition: if he'll drive her around the city looking for a job as a nightclub singer (the lamé dress, after all) she'll pay him double plus a tip if she lands a gig. After a dumbshow of eager interest he turns her down, then changes his mind, launching the pair on a montage of nightclub marquees and the ticking meter. Apparently there's no need of either Eve's voice or her dress in Paris boîtes that night, so they end up at a café frequented by cabbies where Tibor buys her dinner while they swap their stories.

She's a Midwestern chorine with a fatal weakness for cute chumps like Tibor, who crossed the Atlantic in search of a rich sucker. Eve's both a classic screwball heroine and one of Colbert's specialties – a smart dame with more street smarts than common sense. James Harvey, writing about Colbert in Romantic Comedies in Hollywood: From Lubitsch to Sturges, said that "of all the screwball heroines, she's the closest to us, because she remains the most reasonable. In all her triumphs of wit and imagination, she remains stubbornly – happily – untransfigured."

"She always levels with us. It isn't that she isn't magical, but rather that she always shows us what she has up her sleeve – and she's still dazzling."

Eve can see – like the rest of us – that she's going to fall for Tibor so she slips away while he's gassing up his cab and brazens her way into a high society recital party (the dress, you know), using the ticket from the luggage she pawned in Monte Carlo to get past the liveried doorman. Once inside, she's happy to endure an appalling coloratura soprano for the chance to rest in a comfy chair, where she catches the attention of Georges (John Barrymore), who's fighting boredom and sleep until he notices Eve slip off her shoes.

She's about to be rumbled when the dress gets her invited into a private card game, partnered with the ardently flirtatious Jacques (Francis Lederer), a suave playboy who's having an affair with Helene (Mary Astor), Georges' wife. The lunging pace and logic of the screwball shortly makes Eve bait in a scheme by Georges to separate Jacques from Helene. If she can get the handsome young Frenchman to continue to fall in love with her, Georges will put her up at the Ritz and let her draw on his bank account for clothes and other expenses. She gets her rich sucker and he gets his wife back – a good deal all around, apparently.

Gold-digger; gold lamé; heart of gold – Eve is another recurring character from the classic screwball era, albeit nowhere near as calculating as Barbara Stanwyck in Preston Sturges' The Lady Eve. (Perhaps the shared name is a coincidence, but you never know.) And Colbert would play yet another (ultimately failed) gold-digger in Sturges' The Palm Beach Story. You'd think the production code would have had something to say about this sort of amoral behaviour by sexual mercenaresses, but at the end of a decade of global economic catastrophe, you have to assume that audiences had more than a little sympathy for a poor but pretty girl who could use her assets to effect a little redistribution of wealth.

Colbert, Harvey writes, "is the most amoral of all the great screwball heroines. It's a function of her clarity; devastating to the matters-of-the-human-heart style, and very hard, too, on the people who talk of peace of mind or who disapprove of getting something for nothing. Colbert never has to make a flourish of this hardness, or indulge in tough-girl manner of any kind. But in some hay ways she's the toughest of them all – as you know when she turns those wide, attentive eyes on the one who's just said something like 'You threw her out, I hope?'"

Midnight is a strange kind of romantic comedy that abandons Ameche, the killjoy male lead, for most of the middle of the film. While he marshals an army of cabbies to search Paris for Eve, she spends Georges' money insinuating herself into society, claiming to be "Madame Czerny," the wife of a Hungarian baron. The trap Eve and Georges set for Jacques is set to spring at a weekend at Georges and Helene's country house, a place only slightly smaller than Versailles that he used a tradesman's wealth to buy from an impecunious aristocrat.

No disrespect to Ameche or Astor, but John Barrymore's Georges is the only character who threatens to steal the movie from Colbert. By turns dissipate, bored or bemused, Barrymore's Georges is a wealthy man who's discovered too late that he didn't need to become wealthy to find life amusing, since mischief can be bought cheap. He and Eve are immediately simpatico; as Harvey says, they both act like they're freeloaders in Paris' louche high society.

Barrymore was an infamous slow-motion train wreck by the late '30s, a drunken has-been who still had a fine career as a self-parody, playing drunken has-beens. He refused to learn his lines, reading from cue cards on set, and the producers of Midnight cast Barrymore's wife, Elaine Barrie, in a small role as a snobbish milliner in the hope that she could keep him in line during filming.

The Barrymores had an interesting marriage. She met him when, at 19, she sent the 53-year-old Barrymore a fan letter. They married in 1936, between Barrymore's breakdowns, and she served him divorce papers in 1937, two months after their wedding, though they reconciled before it was finalized. More than her small role in Midnight, Barrie is known onscreen for a 1937 short film, How to Undress in Front of Your Husband.

Conspiring with one of her society lackeys (Rex O'Malley in just one of the film's priceless character roles), Helene redeems Eve's luggage from the pawn shop in Monte Carlo and is about to rumble her again when Ameche shows up, her aristocratic "husband" joining her unexpectedly for the weekend, with Georges vouching for his identity to keep his scheme running and, we suspect, to see how the spiralling farce he's set in motion will play out.

Like any good screwball, the final act is when things get really screwy. There's a phone call home to Eve and Tibor's sick child – in reality Barrymore's Georges on the other end of the line, doing baby talk. To keep Tibor from blowing the scheme, she tells everyone that madness runs in the Czerny line and that her husband will take on assumed identities and become violent if anyone tries to object. When he shows up to breakfast in his cabbie clothes with his hack parked on the drive, the long-promised chaos finally erupts and Ameche gets knocked cold by O'Malley swinging a skillet.

The film ends in a courtroom, with no less than Monty Woolley (The Man Who Came To Dinner) as the judge, presiding over Eve and Tibor's "divorce." Militantly skeptical of the poor excuses he sees for ending marriages, he's about to deny theirs when Eve summons up the privilege of every screwball heroine to give a heartfelt speech (in defense of wife-beating, no less; this is a Billy Wilder script) that swings the judge around despite it being wholly a lie.

Harvey observes that the cynicism that makes a Wilder-Brackett (and later Wilder-Diamond) screenplay so tartly delicious "has to be renounced by movie's end – and always is renounced, but in ways that only make us feel queasy about both it and the renouncing." The barb in the tail of Midnight is watching Georges and Helene leave the courtroom arm in arm (although we have no reason to be confident that marriage is saved or worth saving) and Eve and Tibor cheerfully telling the judge that just divorced them that they're off to get married; poor Eve has had to settle for another chump.

Midnight wasn't the last script Wilder wrote before he began his career as a Hollywood director – there would be six more screenplays, including Ninotchka and Ball of Fire, before he made The Major and the Minor in 1942. But his anger at Leisen's changes to his script was a major factor in a years-long push to get behind the camera.

Which might explain why the final scene of Midnight isn't as wry or memorable as "Nobody's perfect" at the end of Some Like It Hot or "Shut up and deal" at the end of The Apartment. But his mark is all over the film, which is remembered today not so much as a Mitchell Leisen film (it's a Hollywood irony that nobody remembers his success) but as lesser Wilder, mostly because he wasn't the director. I'd like to write more about Wilder, but he's such a monolithic figure and so much has already been said that it's safest to approach him from the fringes with a film like Midnight.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.