Horror films work because we want to believe, if only for an hour or two, that things any rational mind would dismiss out of hand are real. Those of us incapable of this suspension of disbelief are doomed to sit through most horror films like an adult forced to sit through a haunted house at a cheap carnival, trying not to ruin the ride for kids or the credulous by sarcastically muttering "Oh, wow. Spooky. Didn't see that coming."

Horror is a genre we tend to overlook since it's almost always an exercise in the dull or risible – or repulsive, given the mainstreaming of extreme gore and the special effects innovations that have made it realer than an autopsy in a minefield. The best we can hope for is to be insidiously drawn in, despite ourselves, and to experience a slow bloom of unease or even dread. (Though to be frank these are emotions I can experience hourly by checking my computer's newsfeed.)

Most critics have seen too many movies, which is why most of them fall into this category. It's also why most critics take the apparently snobbish position of celebrating films and directors who prefer mood to murder. Directors like Jacques Tourneur, who spent most of his career in Hollywood bouncing from B to A pictures and back again – the man famous for making Cat People (1942), a film that's thrilled critics for nearly as long as it's made modern horror fans shrug and wonder "what the heck that was all about?"

Tourneur made Cat People and then I Walked With A Zombie (1943) and The Leopard Man (1943) for producer Val Lewton, head of the horror movie unit at RKO Pictures and a man famous for getting a lot out of very, very small budgets. Tourneur's ability to get a surplus of tension out of a bunch of shadows went over well with both Lewton and audiences in the pre-gore era, earning him a promotion to the A-list, directing Out of the Past (1947) for RKO, one of the greatest film noirs made during the classic era.

The next ten years are typical of a working director's career during the slow-motion decline of the studio system, with Tourneur making everything from westerns, mostly with Joel McCrea (Stars in my Crown, Stranger on Horseback, Wichita) to swashbucklers and adventures (The Flame and the Arrow, Anne of the Indies, Appointment in Honduras) but only a single noir (Nightfall). By 1957 he was in England, working on his first horror film since his Lewton years.

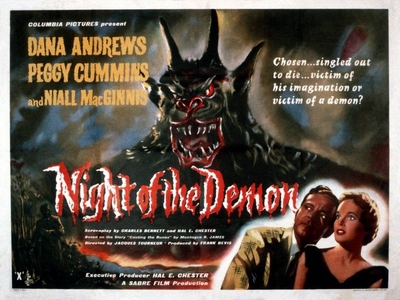

There are two versions of that film. Curse of the Demon was the American release, shorter than the British version, Night of the Demon, and with slightly different edit. For the purposes of this review I'm favouring the UK release, mostly because I like to get value for my money.

Night of the Demon begins with a montage of Stonehenge and a portentous voiceover talking about legends of "evil, supernatural creatures" that men can call forth from another world. We then cut to a man racing his car along a country road at night, desperate to make his way to a country estate where he pleads with a plump man with a pointed goatee named Karswell to lift the curse he's put on him.

Karswell agrees, but his sighs and rolled eyes infer he's hardly being honest. The man arrives home relieved, only to see a huge, monstrous creature tear its way out of a smoky fissure in the darkness and advance steadily upon him. It ends badly.

Tourneur's reputation as a master of unseen menace and implied terror takes a bit of a hit with Night of the Demon, since we're just seven minutes into the film when the monster – a fire demon based on ancient woodcuts – reveals itself in all its clawed, fanged, rubber-suited glory. The director insisted that these scenes were added later, by the producers, and that he had never intended for the monster to be seen clearly except for a few brief frames near the end of the film.

"They ruined the film by showing it from the very beginning with a guy we don't know opening his garage, who doesn't interest us in the least," he told an interviewer in 1965.

The film cuts to an airplane – a Lockheed Constellation, the prettiest airliner ever made – flying through a night sky, its passengers trying to sleep in their chairs. (Finally, a film that confirms that transatlantic air travel was always tedious and uncomfortable.) The least successful is Dr. John Holden (Dana Andrews), whose nap is thwarted by Joanna (Peggy Cummins), the young woman in the seat behind him, her overhead light on, wide awake and at work at her tray table.

It's hardly a meet-cute, but they'll meet again not long after when Dr. Holden discovers that Joanna is the niece of the unfortunate man in the first scene, a fellow scientist and skeptic of the paranormal who was planning to expose Karswell as a devil-worshipping fraud at a conference. Ever the randy Yank, Holden is quick to flirt with Joanna, but they're forced to team up soon enough when Karswell informs him that he's placed a curse on Holden, covertly passing him a rune-covered parchment in the British Museum Reading Room.

Tourneur's film is based on "Casting the Runes," a short story by Montague Rhodes James, a Cambridge don and medievalist and probably the greatest British writer of ghost stories ever. Like Tourneur, James was famous for stories that relied on mood and language to hint at horrible things lurking in the shadows, glimpsed but never revealed.

An antiquarian gifted with an impeccable prose style, James was English to the tips of his detachable collars, so it was imperative that Columbia Pictures should import an American protagonist across the Atlantic instead of trying to transpose his story to any region of the lower forty-eight.

Wartime rationing had ended just three years earlier, but England wouldn't be swinging for a few more years, so the London Tourneur shows in his film is a place where light seems to be scarce, the better to fill every frame, even the ominous corridors of the Savoy Hotel where Holden is staying, with creeping, stygian shadows. (The production designer on Night of the Demon was Ken Adam, later to be famous for his work on villain's lairs in the James Bond films.)

England is an Olde Place, the hedgerows, ruins and copses still thick with pagan horrors barely held back by the excellent hymns of the Church of England or the dour sermons of the nonconformist churches. Out of the city, Holden pays a visit on a family of farmers – hostile, demon-worshipping serfs who speak in a stilted, pre-industrial cadence. It's also eccentric – showcased by a weirdly comic séance that Holden is tricked into attending, where the ladies trill out an old parlour hymn to help a nervous psychic (Reginald Beckwith, one of the film's many small standout performances) get into his trance.

It's all familiar stuff, the setting for countless horror pictures from Witchfinder General to The Wicker Man to the recent A Field in England, but Tourneur's film feels like one of the earliest reports to come from expeditions to this England, a place even more terrible than a two-star hotel at a seaside resort.

Dana Andrews was a notorious alcoholic whose career was in freefall when he made the film; he looks a bit puffy onscreen, and there's a single scene where he seems to slur his lines. But he's perfectly cast as Holden, the rational man trying with increasing desperation to dismiss every strange thing that's happened to him.

Unlike leading men such as Jimmy Stewart or Gary Cooper, Andrews was never believable as a pillar of moral certainty. From his detective in Laura, in love with a dead woman, to the PTSD-scarred ex-bomber pilot in The Best Years of Our Lives, to the arrogant lawyer in Daisy Kenyon, Andrews' strength was flawed, damaged men who could still muster the strength to be heroic – or not.

I always have to double check that the Peggy Cummins in Night of the Demon is the same actress who played the trigger-happy psycho Annie Laurie Starr opposite John Dall in the seedy but indelible noir Gun Crazy (1950). In the earlier film Cummins' high forehead and round baby face made her look like jail bait; in Tourneur's film she's a middle-class Englishwoman in tailored suits, a kindergarten teacher with a psychology degree who's still willing to believe in some darker force in the world.

Actually Irish, Cummins was brought to Hollywood in 1945 by Darryl F. Zanuck, but things didn't pan out and she'd returned to England before being called back to star in Gun Crazy. She liked Hollywood, but went back to the UK nonetheless to get married and resume a career in films that lasted until 1961. She lived long enough to see both Gun Crazy and Night of the Demon become classics, and appeared at screenings of the restored films.

The real standout, however, is Niall MacGinnis (no relation) as Karswell, a character that James had based on the celebrity Satanist Aleister Crowley in his original story. When Holden formally meets with him at Lufford Hall, his country estate, Karswell is entertaining a party of local children, doing magic tricks in a clown getup. There is no better way he could telegraph his sinister nature.

As Karswell, MacGinnis is charming, haughty, solicitous and impatient – a man with an enormous, bruised ego and a mission to prove his superior worth to anyone who doubts it. He conjures up a cyclone to demonstrate his powers to Holden and seems amused that his kitty had transformed itself into a jaguar to attack Holden when he sneaks into his library one night to look for clues. But he's barely in control of the forces he unleashes out of spite, and MacGinnis conveys his poorly-concealed terror beautifully.

Karswell is a fraud, but the dark forces he channels are real, as we know from the demise of Joanna's uncle in the first scene. The only person stubbornly unwilling to entertain the idea is Holden – and the plodders at Scotland Yard. Even his colleagues at the conference – tellingly, an Irishman and a Hindu – won't deny the existence of demons.

This might be why I consider Night of the Demon to be such a successful horror film – not the rubbery fire demon waiting to sear a hole in the night sky, but the relentless assailing Holden's skepticism takes from the moment he steps off the plane and finds himself in a world that doesn't respect his placid American trust in a rational universe. Like the policeman in The Wicker Man who ignores all the signs that he's in a bad place, it's a nightmare that unfolds gradually but remorselessly.

In his book about Tourneur, The Cinema of Nightfall, Chris Fujiwara suggests that this problem of disbelief is at the heart of a cinematic experience: "Holden's problem is that he refuses to submit to the fascination that, for Tourneur, the cinema represents: its power to go beyond 'the reality of the seeable and the touchable.'"

"Karswell's problem, on the other hand, is that he believes in 'things in the dark' too much, to the point that his life depends on it."

In a nutshell, Holden is the critic while Karswell is the horror fan.

Holden's disbelief finally gets worn down by a hypnosis scene at the conference, where he gets Hobart – the son of one of those stoic rural cultists he confronted earlier – to explain the mechanism of Karswell's curse. The man is in a state of catatonia after a brush with the demon when Holden and his Irish colleague use science – drugs and hypnosis – to bring him out of it.

Hobart explodes back into consciousness with a heart wrenching scream and lunges for the camera – what Fujiwara calls "a shock effect unusual for Tourneur" – before being subdued long enough to tell Holden how the rune-covered scroll works. Ironically, the ministrations of these men of science only force Hobart to relive his moment of horror, and he breaks free long enough to fling himself out a window to his death.

The film's climax happens on a train, that most English of things. Karswell's mother, who wants him to abandon his dark magick, lets Holden know that he'll be on the boat train to Calais to get some distance between himself and Holden's appointment with the demon – the curse at the beginning of the film was apparently too close a call.

He rushes to "Clayham Junction" – Clapham Junction by inference, but actually filmed at Watford Junction station between Harrow and Hemel Hempstead – and makes his way on to the train, confronting the anxious and wary Karswell who refuses to accept anything from Holden. He's flustered by the sudden arrival of Scotland Yard, however, who assumed that Holden was harassing him, which gives Holden the chance to slip the parchment into Karswell's coat.

Fleeing the train onto the tracks at Bricket Wood station in Hertfordshire (still there, though much smaller), he sees the demon emerge from the darkness and smoke. What happens next is as inconclusive as the conflict between Tourneau's intentions and the producers' meddling will allow. Scotland Yard assumes that Karswell was knocked down and dragged by the frequent speeding express trains screaming through Bricket Wood station. (This was 1957, of course, before Dr. Beeching's infamous report gutted British railways.) As Holden says to Joanna as he turns away from his chance at a closer look at Karswell's body – the last line in the film – "it's better not to know."

I know there are those who agree with Tourneau that the monster should never have revealed itself as more than an apparition of light and smoke, like the one that chases Holden through the woods earlier, outside Karswell's estate. Those people apparently cover their eyes during the scenes where the demon appears, imagining a director's cut that never was.

And yes the monster is obvious, low-budget movie trickery – a stiffly sprinting stop-motion creature in the distance, a man in a rubber suit when it corners Karswell on the tracks. But that inconsistent, inhuman movement is undeniably eerie, and whoever's in that suit really sells the demon, so I have to admit to a brief shudder and recoil whenever the villain gets his demonic comeuppance.

Early in the film, Karswell does his bit to assail Holden's belief in reason by asking him: "When does imagination end and reality begin? Where is this twilight, this half world of the mind you profess to know so much about? How can we differentiate between the powers of darkness and the powers of the mind?"

It's a fair question, and one that we all have to ask ourselves when we sit down to watch a movie made to terrify us. Most of the time I vote with my feet and choose not to watch something that will either bore or disgust me. But occasionally, when I have the chance to watch a gothic confection like Night of the Demon that shows its seams and strings, I want to go some place strange, built by storytellers with talent like Tourneau and James. And in this case this critic is saying "I want to believe."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.