Something strange was happening in the middle of the 1970s, and I'm not talking about stagflation, Watergate, platform shoes, glam rock, terrorism, the oil crisis, hijackings and the AMC Gremlin. Maybe it was because of that – or maybe it was all just a reaction to the social and cultural eruptions of the late '60s – but for a while movies seemed to be going in full reverse, back thirty, forty and even fifty years.

Hollywood's last long look into the past had been in the '40s, when there was an explosion of "Knickerbocker" movies set in the decades before the First World War – pictures like Meet Me In St. Louis, Life With Father, Easter Parade, On Moonlight Bay and many more. This eruption of nostalgia wasn't shocking – America had been shaken by the one-two punch of the Great Depression and World War Two, so the last long peaceful moment of splendid isolation between Reconstruction and the sinking of the Lusitania probably looked like the "good old days," especially to the many people still alive who had fond memories of childhoods back when horses still competed with cars on the roads.

For those people still alive in the '70s, nostalgia for the turbulent decades leading up to Pearl Harbor might have been strange, but the lingering hangover from the excesses of the '60s made bread lines, mass unemployment and conscription seem finally like something worth remembering fondly. What I've never been able to explain is the attraction this nostalgia had for Baby Boomers who were, by now, not just a significant portion of cinemagoers but very much involved in the making of Hollywood movies.

You might blame the success of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 for this, among other things. For the young fans of Arthur Penn's film, this was truly a period picture, set in an exotic time before their birth. After that the floodgates opened slowly but surely – with They Shoot Horses, Don't They? in 1969 and Bernardo Bertolucci's The Conformist, in 1970, Boxcar Bertha in 1972 and then Francis Ford Coppola's Godfather films in 1972 and 1974.

Paper Moon, Dillinger, Emperor of the North Pole and The Sting came out in 1973, and The Great Gatsby and Chinatown in 1974. But the next year was the crescendo, with Capone, Lucky Lady, The Day of the Locust, Hard Times, Funny Lady, Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze, The Hindenburg, The Great Waldo Pepper, The Fortune, Hearts of the West, At Long Last Love and the near-pornographic Inserts all hitting theatres in 1975. If you spent the mid-'70s in a movie theatre you wouldn't know what decade it was, and that was probably a blessing.

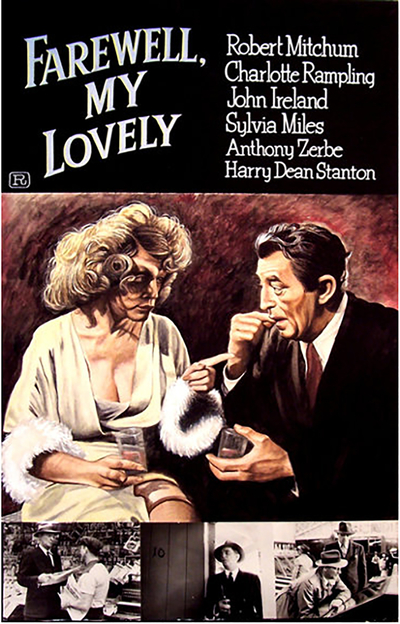

This is where Farewell, My Lovely comes in – an adaptation of a Raymond Chandler novel starring Robert Mitchum, whose career was just getting started when Dick Powell played Chandler's hero Philip Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet, a 1944 film version of the novel. It's doubtful Mitchum would have been cast as Marlowe back then – too young and callow – but by 1975 he was one of the few really credible choices left to play the famous, wise-cracking, world-weary private detective.

The 1944 film – the second adaptation of Chandler's novel after The Falcon Takes Over, a 1942 George Sanders film that borrowed the plot of the novel – is considered one of the first film noirs, along with Double Indemnity. The 1975 version, directed by former photographer and commercial director Dick Richards, is considered one of the best examples of neo-noir, a modern subgenre that borrows the style, mood and plots from classic noir while setting stories in period or contemporary locales, or even in the sci-fi future; it's a sprawling, promiscuous genre that includes everything from The Long Goodbye to Night Moves to Body Heat to Basic Instinct to L.A. Confidential to Mulholland Drive to Blade Runner.

The film is elegiac, beginning with the neon sign of a hotel room reflecting on a window where Marlowe is in hiding from both the cops and the bad guys; in a voiceover the private detective talks about how the summer was long and hot, and made him "realize I was growing old." It's hard not to look at Mitchum's lined face and agree. It's 1941, Pearl Harbor is months away, and Joe DiMaggio is on a famous batting streak that will last until a mid-July game against what were once called (at least until the end of this season) the Cleveland Indians.

In a long flashback told to Nulty (John Ireland), an L.A. police lieutenant under pressure to nail a series of killings on Marlowe, the detective recalls how it all started when a huge ex-boxer, bank robber and recent prison parolee named Moose Malloy (real life ex-boxer Jack O'Halloran in his first movie role) hired him to find Velma, the girlfriend who hadn't written or visited him in six years.

The big mug takes Marlowe to Florian's, a seedy former nightclub on Central Avenue where Velma had danced. Like most of Central Avenue at that point it's now a "colored" joint, and Moose's persistent inquiries about Velma end with the owner dead after he tries to pull a gun on him.

Marlowe barely begins the search for Velma when he's hired by a sweetly-scented character named Lindsay Marriott (recall how everyone in The Maltese Falcon comments on the perfumed aroma of Peter Lorre's effeminate Joel Cairo) to provide the muscle for the late night ransom of some rare jade, stolen from a rich lady friend of Marriott's. Things go badly, Marlowe is sapped unconscious, Marriott ends up dead, and Marlowe is the prime suspect in what is becoming a string of murders.

The film is shot in colour, but its tones are muted, and everything is rubbed with a warm brown like the nicotine veneer in an old diner. Farewell, My Lovely might be an obscurity today but it wasn't a low-budget production. The cinematographer, John Alonzo, had shot Chinatown the previous year, and production designer Dean Tavoularis was a legend, the man who had so evocatively dressed the sets of Bonnie and Clyde and the Godfather films. Richards made a point of filming on location, combing L.A. for what remained of Chandler's Los Angeles.

Tavoularis apparently had a warehouse full of props and furniture that he used to fill the dance halls, bars, offices, diners, hotel rooms, apartments and amusement arcades where the film takes place, and throughout the picture Mitchum is dressed in a pinstripe suit dragged out of storage at the Fox costume warehouse, once worn by Victor Mature.

"I'm not wearing this old fucking thing," Mitchum complained to Richards. "Victor Mature farted it all up."

I can't speak for the Boomers in the audience when Farewell, My Lovely was released, but the movie had a deep resonance for me when I saw it later on late night television. You could still find pockets of that old wartime world, especially in the vintage clothing shops and derelict stretches of downtown Toronto where an aspiring but pitifully suburban teenage punk rocker like myself spent his spare time after school and on weekends.

I had been raised by parents with adult memories of the '20s, '30s and '40s, and the state of history education at the time was still competent enough to impart a vivid sense of the turbulent decades through which we had recently passed. I was getting into old movies – the Classic Hollywood of TCM as it would be known – and while I knew that Farewell, My Lovely wasn't an old picture, it felt like – and still feels like –an eerily hyper-accurate simulation of the past.

While only three decades or so gone when it was made, that past was quickly receding into the distance, as exotic and strange as the Knickerbocker Nostalgia of the '40s. It was the kind of film that felt like you could walk into it and leave the present day behind, and part of me is still waiting to find the door that will take me there.

While the look of Farewell, My Lovely was evocative, it was definitely a film that couldn't have been made in 1944. Chandler was fond of sleazy elements in his stories, and film noir was happy to go there – remember Geiger, the blackmailer and pornographer in Howard Hawks' giddily incoherent 1946 version of The Big Sleep? – but Dick Richards' filming of Chandler's story takes a deep dive into the corruption and bigotry of Los Angeles in its prime.

Marlowe's search for Velma takes him to Tommy Ray, a trumpeter who once led the band at Florian's, now living with his black wife and child in a rundown hotel across Central from the club. Tommy sends Marlowe to talk to Jessie Florian, the widow of the club's onetime owner, a blowsy drunk living in a filthy house in what is supposed to be L.A.'s Bunker Hill neighbourhood, a favorite noir filming location which had been bulldozed off the map by the time Farewell, My Lovely was shot.

Sylvia Miles is indelible as Jessie Florian; the role got her a second Academy Award nomination after her performance in Midnight Cowboy. Latching on to the mickeys that Marlowe brings her, flirting with the detective in rolled stockings and a satin dressing gown, she casually throws around the "n-word" in off-handed comments about how Tommy's wife had been the ruin of his career.

Marlowe is summoned to meet with Helen Grayle, the rich lady friend of Marriott who wants him to find out who stole her necklace and killed her friend. She's the wife of Judge Grayle, one of L.A.'s most powerful men, a sickly cuckold in abject thrall to his beautiful, much younger wife. (If only to thrill fans of hardboiled fiction and pulp novels, Richards cast novelist Jim Thompson, author of The Getaway, The Grifters and The Killer Inside Me to play Judge Grayle.)

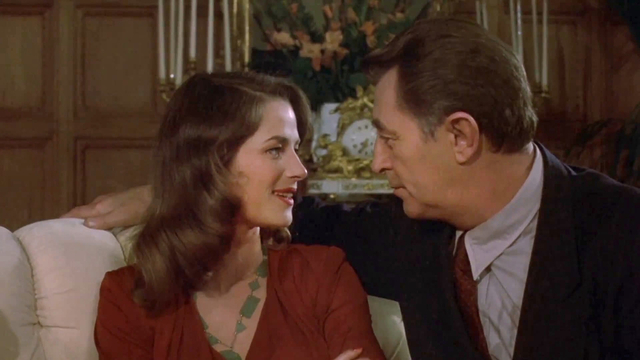

Fashion model and art house star Charlotte Rampling, seen topless in an SS uniform in Liliana Cavani's The Night Porter the year previous, was cast as Helen, and Richards had her done up like the young Lauren Bacall. In a hilarious interview with Roger Ebert to promote the film, Mitchum recalled that Rampling "arrived with an odd entourage, two husbands or something. Or they were friends and she married one of them and he grew a mustache and butched up. She kept exercising her mouth like she was trying to swallow her ear."

"I played her on the right side because she had two great big blackheads on her left ear, and I was afraid they'd spring out and lodge on my lip."

Whatever the circumstances of the filming, there's palpable chemistry between Mitchum and Rampling. (She was 28 when the film was shot; Mitchum was 57.) After sending her husband away for his nap, she pours a couple of very deep highballs and invites Marlowe to join her on a vast settee in their monumental house. Marlowe replies that he'd been thinking about that "ever since you first crossed your legs."

"These damned things are always up around your neck," Rampling sultrily complains, letting that double entendre land like a hand grenade.

They end up in a clinch on the couch, interrupted when Marlowe notices Judge Grayle at the door of the room. That's a bit too much, even for him, and he reluctantly extricates himself from Rampling's limbs. "Jesus you're old fashioned, aren't you?" she says.

"Only from the waist up," Mitchum replies, a quip that comes off as ad libbed based on the genuine laugh it gets from Rampling.

Marlowe's search for Velma ends up getting him sapped again, and he's taken by some gunsels to a notorious but high end brothel run by Frances Amthor, a diesel dyke played with so much real menace by Kate Murtagh that she makes O'Halloran's Malloy seem like Joel Cairo. (Trivia for today: Murtagh was the cover girl on pop prog band Supertramp's hit 1979 album Breakfast in America.)

In Chandler's novel Amthor was a man, a quack psychic, but for the 1975 film the character is combined with Dr. Sonderberg, a drug dealer who locks Marlowe up in his clinic and shoots him full of dope to keep him quiet. Murtagh's Amthor was based loosely on Brenda Allen, a brothel owner protected by the police who created a scandal for the LAPD when she was arrested in 1948. Struggling to rouse himself from his drugged stupor after a surreal nightmare sequence that pointedly echoes one in Murder, My Sweet, Marlowe finds Tommy Ray's corpse in his room.

He escapes, exploring the brothel and its circle-of-hell rooms – topless girls, sobbing men – before he confronts Amthor with a gun, but she barrels past the doped-up detective when she's told that her girlfriend is in bed with one of her gunsels (a pre-Rocky Sylvester Stallone). She savagely beats the naked girl before the gunsel shoots her dead. The whole brothel sequence doesn't add much to the plot – a typically convoluted Chandler contrivance – but it injects an unsettling creepiness that would have been unthinkable when the Production Code was still in effect.

Producer Elliott Kastner had dreamed of making a film from Chandler's books for years. He was finally able to afford the rights to The Long Goodbye, one of the few unfilmed Chandler properties, and planned to cast Mitchum as Marlowe but the studio, United Artists, said he needed to go with a younger face. He ended up with Elliott Gould as the detective and Robert Altman as director. It was a flop, but Kastner persisted and got the rights to Farewell, My Lovely two years later, along with the clout to cast Mitchum.

Mitchum began to clash with Richards as the shoot wore on, becoming impatient with the director's constant fussing with details and encouragement of on-set improvisation. In Robert Mitchum: Baby I Don't Care, a 2002 biography, author Lee Server recalls how Richards' methods paid off.

In a scene with Sylvia Miles, Richards encouraged the actress to sing a song while describing her old act for Marlowe. They chose Jule Styne's "Sunday" on the spot, mostly because Mitchum remembered the words, and despite not having clearance to use the song. Miles starts the song but Mitchum joins in, Miles breaking into tears as Mitchum finishes the verse.

"A beautiful scene, perfectly staged," Server writes, "you can hear the flies buzzing, feel the dust floating in the tatty living room, Miles blending the poignance and the awfulness of the aged vaudevillian, Mitchum observant, gently insidious – an entirely convincing demonstration of a detective's particular fact-gather and people-burrowing skills in action."

Filming took Mitchum to some of the city's seediest neighbourhoods – places he remembered from his own life, when an uncertain, often dire childhood led to some hardscrabble years as a struggling actor. One night he was filming at Sixth and Main, just between L.A.'s Financial District and Skid Row, not far from the Rescue Mission where he got a bed and a meal as a teenager.

"Forty years had come and gone," writes Server in his biography. "Nothing much had changed. The winos and the drifters and the junkie hookers still roamed these streets as before. A few who could make it to their feet straggled over to check him out, gave him a toothless grin, as if recognizing an old friend. My people, Mitchum thought. He peeled off singles and five spots for each. They took the handout, and a cigarette, thanked him boisterously or mumbled incoherently, staggering back to the shadows."

"An old cop watched him working. Man was way past retirement age. How long had he pounded this miserable beat on the graveyard shift? The old cop stared at him and after a while he came over, looked him up and down. He said, 'So you're back.'"

While writing this piece I realized with a start that I am as old as Mitchum was when he played Marlowe. I'm no male model but I don't look nearly as ragged as Mitchum does in the picture, but then again I haven't lived a life nearly as strenuous, even if you don't count the reefer busts and calypso records.

Farewell, My Lovely did well when it was released, earning well past its budget when NBC bought the TV rights for $1.2 million. But the nostalgia boom in movies had played itself out. The next year saw the release of Hal Ashby's Woody Guthrie biopic Bound for Glory, but Jaws helped give birth to the summer blockbuster and the release of Star Wars in 1977 made studios want to look forward to the sci-fi future, not backwards to the smoke-filled past.

Richards' film did well enough to inspire Kastner to produce a remake The Big Sleep three years later, with Mitchum returning as Marlowe and Sarah Miles and Candy Clark cast in the roles played by Lauren Bacall and Martha Vickers in Howard Hawks' 1946 version. Richards didn't return, however, and Michael Winner was the director of a film that changed the setting of Chandler's story to modern-day London.

Joan Collins was frightened of getting hurt by Mitchum during filming of a fight scene. "Honey, I'm an actor," Mitchum reassured her, "and I know how to play rough. I've been doin' this stuff for about a hundred years so I'm not about to hurt an actress in a scene, 'specially not in this piece of crap."

Despite the incredible casting – Collins, John Mills, Edward Fox, Richard Boone, Oliver Reed and Jimmy Stewart, no less! – the film wholly lacked the chemistry and mood of the previous picture and flopped. Let us never speak of it again.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.