The great songwriting team of Livingston & Evans came to an end twenty years ago - October 17th 2001 - with the death of Jay Livingston. His younger brother, Alan Livingston, co-wrote a favorite song of mine (if not of Gavin McInnes), but, other than that, I would have to account Jay the better songsmith. Everyone knows at least one Livingston & Evans song, because, starting next month, you're going to be hearing "Silver Bells" at the mall and at the diner in high rotation until Christmas Day. But that's a tad premature, so here's an alternative from the team:

When I was just a little girl,

I asked my mother, 'What will I be?

Will I be pretty? Will I be rich?'

Here's what she said to me:Que Sera Sera

Whatever will be will be

The future's not ours to see

Que Sera Sera...

Back in 1956, Doris Day's fatalistic anthem was simultaneously Number One in Britain and Number Two in America, albeit under different titles. On one side of the Atlantic, it was "Que Sera Sera (Whatever Will Be Will Be)" and on the other it was "Whatever Will Be Will Be (Que Sera Sera)". On the film credits, it's "Whatever Will Be". But whatever the title will be it was a big hit. It's a strange not quite categorizable song that's lingered in the memory. Miss Day's recording is featured in the movie Girl, Interrupted, while Heathers prefers the Sly and the Family Stone version:

Regardless of performer, whenever it turns up on the big screen (which is remarkably often), you get the vague feeling the film-maker is trying to pass the song's use off as semi-parodic in order to disguise how much he likes it. Yet I notice a lot of younger female vocalists seem to like the Doris Day oeuvre in general, and this song in particular. A few years back, I was sitting in a restaurant in Miquelon, the less populated island of the French colony Saint Pierre et Miquelon, and a contemporary version of "Que Sera Sera" came over the speakers. I asked the charming waitress who was singing it, and she told me it was a vedette from Québec called Ima:

A couple of weeks later, I was in a joint in Vermont, and another young chanteuse sang it in contemporary style, somewhat less successfully. A year or so on, I was back in Miquelon at the same restaurant and inquired of the owner about the aforementioned charming waitress: She had committed suicide in France, and for a while the lyrics rang a little mordant with me - "Whatever will be will be. The future's not ours to see", and I certainly did not see that.

Beyond such personal associations, the song remains Miss Day's. "Que sera sera," Doris told me a few years back. "That's really my philosophy." Tell it to Buddy, Bill Clinton's late pooch. At one point, Miss Day wrote to the White House demanding he be neutered – the dog, that is. Of all the potential perils the modern world has to offer, the possibility that Doris Day will publicly call for your castration must rank as pretty low. Nonetheless, Buddy's perky blonde nemesis was insistent. If the President's chocolate lab were to be left intact, she argued, he would be liable to prostate problems which might cause embarrassing urinary accidents on grand White House occasions. "Whatever will be will be," as Buddy might well have barked in a withering riposte. "The future's not ours to see. Que sera sera." But, evidently, Doris was by then more proscriptive than she was when she introduced her boffo shoulder-shrugging hit. She had not cared for it when she first heard it, although it became her biggest hit and the theme of her TV show.

It was written by Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, and, if you've never heard of 'em, don't worry about it; they never did. The closest thing to celebrity was when they got to play the songwriting team bashing out a parody "Buttons and Bows" at the New Year's party in Sunset Boulevard. Aside from that moment of glory, when kids met Jay Livingston, they were impressed not that he was the guy who wrote the theme song to "Mister Ed", the celebrated TV show about a talking horse, but that he was the guy who sang it, too. He'd done it on the demo, and the production company decided they liked it just as it was, with Livingston warbling:

A horse is a horse

Of course of course

And no one can talk to a horse of course

That is, of course

Unless the horse

Is the famous Mister Ed...

Other than that moment of vocal glory, Jay belonged to a line of Hollywood songwriting teams who, unlike their Broadway counterparts, never became household names - Warren & Dubin ("I Only Have Eyes For You"), Robin & Rainger ("Thanks For The Memory"), Fain & Webster ("Love Is A Many-Splendored Thing"), and Livingston & Evans.

I met Livingston over the years at various songwriters' gatherings. He was a thin man who was generally the tallest composer in the room. "You're Ray Livingston," I said, introducing myself. "No, I'm Jay Livingston," he said. His partner was Ray Evans. In the absence of Ira and Myra Gershwin, they were the only songwriting team that rhymed. The only other professional Ray and Jay partnership I know of are two financial advisors who used to host "The Ray & Jay Financial Show" Monday evenings at 7pm on CJAD Radio in Montreal.

Livingston & Evans were partners for over sixty years. Every once in a while, they tried the theatre but, as Livingston put it, "I hated Broadway. Everyone was so superior." So they stuck to Hollywood and wrote "Buttons And Bows" for The Paleface, "Mona Lisa" for Captain Carey USA and the only good urban Christmas standard, "Silver Bells", which Bob Hope sang in The Lemon Drop Kid. A lot of the rest of the time, they wrote title songs, which isn't the easiest occupation. If you asked him nicely, Livingston would sing the title song he composed for The Mole People, a 1956 sci-fi film about a lost community of albinos living under the earth's surface:

Well, that's assignment work: no composer walks down the street going, "I've got this great title for a song: 'The Mole People'." But to pull it off with such brio is impressive: Livingston & Evans were hired to write a number about mole people and they almost dug themselves out of that hole, people.

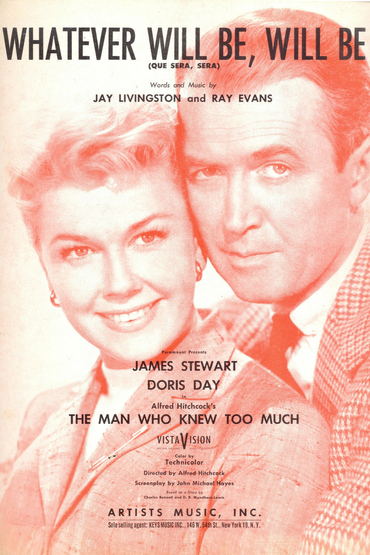

"Que Sera Sera" was a deal-clincher: Alfred Hitchcock wanted Jimmy Stewart for The Man Who Knew Too Much, his 1956 Hollywood remake of one of his early British films. But Stewart's agency, MCA, told Hitchcock they'd only give him Stewart if he took another of their clients, Doris Day, as co-star. So Hitch agreed. Then Doris demanded a song. So Hitch caved again.

"We had never met him before," Ray Evans recalled a few years ago. "And Hitchcock said, 'I don't know what kind of a song I want, but it's got to be the kind of song that a mother would sing to a little child.' The picture takes place in Europe and North Africa. Jimmy Stewart is a diplomat-" Mr Evans' memory was a little faulty here: Stewart was playing a doctor. "-and Hitchcock said, 'I've written it into the plot because it's the part when the little boy is kidnapped, when Doris Day finally finds him. She finds him by singing the song and hearing him echo her in the distance and she knows where he is.' But we got the title 'Que Sera, Sera' and wrote it on that basis and then we had to play it for Mr Hitchcock and he said, 'Gentlemen' - and Jay could imitate him very well. I can't do that - he said, 'Gentlemen, when I first met you, I didn't know what kind of a song I wanted. That's the kind of a song I wanted.' He said, 'Thank you very much. Goodbye.' And we never saw him again."

In the picture, with Doris Day singing to a young child, you can sense the director doesn't know what he's got - the artlessness of the song seems to have thrown poor old Hitch. But he liked it enough to make it the linch pin of the plot, used it the final scene to effect the rescue of the kid:

Miss Day didn't like it. She thought it was a child's song and would never be a hit, so she did it in one take and said "That'll do", and it became the biggest hit of her career. But Livingston never cared for the number, either. He prided himself on being able to "write simple", which most composers are too insecure to do, but he thought "Que Sera, Sera" was too simple. (His favorite song was "Never Let Me Go", because he was proud of the chord changes, which the jazz guys love.)

I once mentioned to Livingston that I'd heard "Que Sera, Sera" sung by baying Millwall fans on the footie terraces. "What words do they use?" he asked.

So I told him:

Mi-illwall, Millwall

Millwa-all, Millwall, Millwall

Millwa-all, Millwall, Millwall

Mi-illwall, Millwall.

(Repeat until knife fight.)

"You can tell they're not professionals," he said. "All those melismas."

But English footie fans love the song. If your team gets to the FA Cup final, you sing:

Que Sera Sera

Whatever will be will be

We're going to Wem-ber-lee

Que Sera Sera.

And if England get to the World Cup you sing

Que Sera Sera

Whatever will be will be

We're going to Ger-ma-nee [or It-a-lee, or any other trisyllabic venue ending in a long "e"]

Que Sera Sera.

As a rule, Evans wrote mostly words, Livingston mostly music, but they never formally divided up the credits because, in an arrangement that permanent, the point is moot. Generally speaking, Evans would write some lyrics first, Livingston would pick out the lines he liked or images he took a shine to and build a tune around them, then Evans would rework the lyric. Usually, lyricists are more sensitive to tunes than composers are to words, but Livingston knew how to make the lines sing. I love the slightly goofy, introspective formality of "Mona Lisa":

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there

And they die there...

Was it Dorothy Parker who lifted that for some one-sentence play review? "It just lies there and it dies there." The real skill lies in writing those words to those notes, the peculiar combination that plants a line in the language. It's a perilous thing, too – Evans originally wanted to call "Silver Bells" "Tinkle Bells", until Livingston's wife pointed out he'd have to be nuts. Instead of a seasonal blockbuster, he'd have a song fit for the formal castration of incontinent White House dogs and not much else. "I never thought of that," grumbled Evans. "That's a woman's word. I was very unhappy because I hate to rewrite. I was always lazy."

But there's something about "Que Sera Sera" that transcends mere hit status. Maybe it's what Livingston regarded as the excess simplicity or Evans' deployment of a foreign phrase but it's one of those numbers that sounds as if it's been around longer than it has, belonging to the same pseudo-folk category as their earlier hit "Golden Earrings". It's pretty much a universal folk tradition, too. Evans claimed to have heard it played by the house band in the hotel he was staying in on a trip to Afghanistan. Still, though it was close to his own, the philosophy is bunk. Whatever will be is not what will be: We have the capacity to shape events and, if we don't, they may well turn out to be far less congenial for us than they were for Doris Day:

When I grew up and fell in love

I asked my lover, 'What lies ahead?

Will we have rainbows day after day?'

Here's what my lover said:Que Sera Sera...

But, whatever the dopey fatalism, it's what Betty Comden calls a singable song, a song you don't just enjoy listening to but you enjoy singing. A month before he died in 2001, Jay Livingston attended an all-star gala in Hollywood and was serenaded by the audience with the tune he thought was too simple. They couldn't have managed the chord changes in "Never Let Me Go", but they were on top of this one:

Que Sera Sera

Whatever will be, will be

The future's not ours to see

Que Sera Sera

What will be will be.

~Don't forget many of Mark's most popular Song of the Week essays, including "My Funny Valentine", "Summertime" and "As Time Goes By" are collected together in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

If you're a Steyn Clubber and you feel this is not the bestest column what am, feel free to weigh in in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.