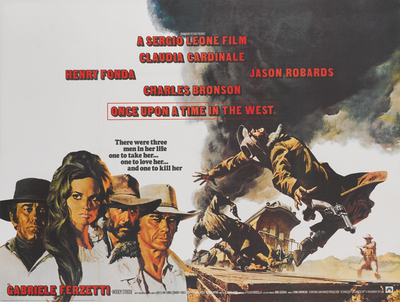

People who complain about Sergio Leone's western epic Once Upon a Time in the West being too long – and they've been complaining about that since it came out in 1968 – obviously value their precious time. Luckily those people have the film's opening credit sequence, a magnificent scene that sums up what westerns are all about in fifteen of the greatest minutes ever put on film.

It begins at the railway station in Cattle Corner – a windswept outpost in the American southwestern desert with an improbably vast train platform made of wooden railroad sleepers laid out in endless rows. Three men ride up wearing long yellow dusters. These are dangerous men, each one radiating some particular aspect of menace.

The wizened stationmaster – the first of many grotesque background characters we'll meet in Leone's film – tries to sell them tickets for the next train, but the leader of the group, a cockeyed older man, locks the stationmaster in his own safe while another man bares his teeth and chatters dementedly at a songbird in a cage. They're watched impassively by a tall, powerful-looking black man, who takes off his duster and wraps it around the pommel of his saddle as the three settle in to wait for the train.

At least two of the gunmen would have been familiar to moviegoers or fans of TV westerns. The cockeyed gunman – called Snaky in the credits – was played by character actor Jack Elam, who had been a heavy in every TV western show from Gunsmoke to Bonanza to The Rifleman to F Troop to Have Gun, Will Travel. The black gunman – Stony in the credits – was none other than Woody Strode, one of the first African-American players in the NFL, whose celebrity and imposing demeanor had helped launch a film career, with parts in The Ten Commandments, Spartacus, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and the heroic title role in John Ford's Sergeant Rutledge.

The third gunfighter – the apparently demented bird-threatener called Knuckles in the credits – was less well known to US audiences. Al Mulock was born in Toronto, the great-grandson of a postmaster-general and chief justice of Ontario. He made his way to Lee Strasberg's Actors Studio in NYC before moving to Europe, where he worked in British films for a few years before a role in Leone's The Good, The Bad and The Ugly led to a brief run of parts in other "spaghetti westerns."

He killed himself during the filming of Once Upon A Time In The West by jumping from his hotel room outside Granada, still wearing his villain's wardrobe. While being taken away in the ambulance, Leone apparently pleaded that they had to get the costume off Mulock, as it was still needed for filming.

When casting A Fistful of Dollars a few years earlier, Leone tried to get Henry Fonda (his favorite actor) and then Charles Bronson to play the Man With No Name; instead he was forced to cast Clint Eastwood, a young actor known only to TV audiences. When it came time to cast Once Upon a Time in the West Leone had a much bigger budget, and apparently tried to get Eastwood, Lee van Cleef and Eli Wallach – the three "heroes" of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly – to do cameos as the three gunmen. Thankfully he was frustrated again; it's hard to imagine the film's opening scene without Elam, Strode and Mulock.

The gunmen occupy themselves with various bits of business while waiting. Knuckles runs a hand through a trough while watching the horizon, then begins systematically cracking his – yes – knuckles. Stony stands under the station water tower; when condensation beings dripping on his forehead, he puts on his hat and collects the water in the brim, which he drinks with obvious pleasure as the train announces its arrival with a screaming whistle.

Snaky takes a seat on a bench; when the station telegraph chatters to life, he silences it by yanking out its coiled, cloth-covered wires. He's then assailed by a fly that crawls all over his mouth and chin. When it alights on the end of the bench, he traps it in his gun barrel with a lightning move, then happily listens while it buzzes away inside his weapon.

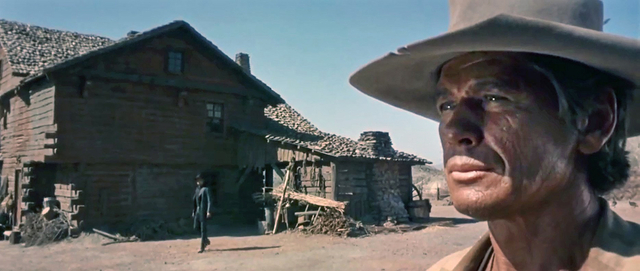

The train pulls in; when nobody gets off, the gunmen shrug and get ready to leave. Just then they hear the sound of a harmonica; a man is standing on the far side of the tracks, holding a valise with a gun tucked into a blanket under the handle.

Up till this point there hasn't been a single note of music. The whole of the dozen minutes it's taken for the gunmen's quarry to arrive has been soundtracked by the fly, the dripping water, the wind, the telegraph and the rusty squeak of the station windmill. The three notes played by the man with the harmonica – Charles Bronson, known throughout the film simply as "Harmonica" – are a wheezing little threnody, a baleful motif that will follow the character around. They're little more than the sound you get when you stuff a harmonica in your mouth and breathe in and out. Their meaning will be revealed at the end of the film – "at the point of death."

The man with the harmonica asks the gunmen if one of them is Frank. Frank sent them, Snaky tells him. Harmonica asks if they brought a horse for him.

"Well, looks like we're shy one horse," chuckles Snaky.

Harmonica slowly shakes his head.

"You brought two too many."

(Leone's film is famously taciturn; in nearly three hours of film, there are only fifteen pages of dialogue.)

And so the inevitable moment arrives. It's an unfair fight – three to one. Snaky draws first but Harmonica is faster, loosing three rapid shots before Stony fires his sawed-off rifle, sending Harmonica spinning to the ground. The gunshots in this film are huge and throaty, more like cannon fire than rounds from a pistol or rifle. His legs planted wide astride the wooden planks, Stony falls like a toppling colossus.

If your time is too valuable to sit through the remaining hundred-and-fifty minutes of Once Upon a Time in the West, you could probably turn your attention elsewhere now, having seen the greatest opening sequence in (one man's opinion) the greatest movie ever made.

Of course what you'll miss is the next scene, probably the greatest introduction to a movie villain ever – the moment when the movie's famous stinging fuzz guitar motif erupts from the screen for the first time, near the end of the cold-blooded massacre of an innocent family preparing a banquet for guests at their homestead deep in the desert. The killers are another group of men in long yellow dusters, led by Frank – none other than Henry Fonda, his clear, bright blue eyes full of cold, dead menace instead of Tom Foad or young Mr. Lincoln's kindness and empathy – who tells his henchman that he's going to have to kill the only survivor now that he's said his name out loud.

Frank seems to regret this at first, but his eyes brighten, a smile tugging his tight mouth upward as he pulls out his revolver, those blue eyes never leaving the face of the little red-haired boy who knows he's about to die.

Ennio Morricone wrote the music for all of Sergio Leone's films. I won't bother testifying to Morricone's brilliance since it's been done a million times already, over the course of a career where he wrote soundtracks for hundreds of movies from The Bird with the Crystal Plumage to The Battle of Algiers to Days of Heaven to Bugsy to The Mission to Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Morricone knew Leone when they were boys, at a primary school in Travestere, a working-class suburb of Rome. They met again in 1963 when Leone needed a composer to write the soundtrack for the film that would be A Fistful of Dollars.

For Once Upon a Time in the West he wrote (again, one man's opinion) the greatest film soundtrack ever, the genius of which is only barely revealed with those three wheezing notes from Bronson's harmonica. For Jill, the high-class New Orleans whore who married Brett McBain – the owner of that desert homestead, murdered with his family by Frank while her train arrived – Morricone wrote a lush, yearning, romantic theme, an orchestral cloud holding aloft a wordless melody sung by Italian soprano Edda Dell'Orso, which fills the screen whenever Claudia Cardinale's Jill appears.

He wrote a jaunty but wary little tune for Jason Robards' Cheyenne – the Mexican bandit whose gang wears trademark yellow dusters, framed by Frank for massacring the McBains. It's a quizzical melody that slows the film down even further whenever it's played, on the muted strings of a banjo, on the keys of a saloon tack piano, and finally whistled. Jill and Cheyenne, the whore and the bandit, both with hearts of gold and the repositories of humanity at the heart of the film's epic story.

And then there's Frank's theme, the lacerating, knife-edged melody played by that buzzing electric guitar, which drives the tension to an unbearable pitch - often in a duet with Harmonica's mournful three notes in the background. I have played it on every guitar I've ever owned; I may have it played at my funeral.

There can be nothing unambitious about a film that's nearly three hours long. Leone's film is a western about westerns; when working on the story together with fellow directors Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, the three cineastes borrowed names, plot elements and settings from The Iron Horse, High Noon, The Searchers, Shane, The Comancheros and other classic westerns, with a particular emphasis on the films of John Ford. They were being postmodern, before it was fashionable.

And as much – if not more – than other westerns it's a film about the West, a place and a time and a period of history whose importance was well understood by 1968. The frontier thesis, also known as the Turner thesis, formed around "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," a paper delivered to the American Historical Association in 1893 by Frederick Jackson Turner. In it, Turner said that American history had been formed and shaped by the constant presence of an undeveloped frontier on its western edge, from the formation of the original thirteen colonies to the closure of the frontier in the 1880s, when the railroads had created a network across the country and the last large tracts of "free" land had been settled.

Besides the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, which would continue to influence American social and political culture for decades to come, the conflict at the heart of the frontier was between the freedom and possibilities inherent in the West and the economic imperatives of the East, which seeks to control the country in formation. In Once Upon a Time in the West, the East is embodied by Mr. Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), the owner of the railway making its way across the desert, through Cattle Corners on its way to Sweetwater, the McBain homestead, purchased by Brett McBain because he knew there was nowhere else for the railway to go.

Morton is a powerful but pitiful figure, a rich man dying from a mysterious "tuberculosis of the bones" who travels in a luxurious, customized railway car. What he can't do – and there's a lot he needs to do – he deputizes to Frank, the muscle he hired when his railway car left on its journey within sight of the Atlantic, on its way to the Pacific coast. By the time we meet them, Morton has become impatient with Frank's thuggish, murderous methods, while Frank has come to envy Morton's style and wealth.

On their way across the country the two men – Morton with capital and development, Frank with homicidal lawlessness – are killing the West and its potential to express the utopian and agrarian realization of liberty inherent in the vision of founding fathers like Jefferson. Just how accurate this vision of America was or is has been a matter of debate since Turner published his thesis, but Leone is just one of a long line of historians, writers, artists and western directors who found it compelling.

But don't take my word for it. In a scene near the showdown at the end of the film, Frank and Harmonica look over Sweetwater, now a hive of activity as Jill oversees the construction of a new town just as the railway arrives there. Harmonica observes that Frank is no longer trying to be a businessman like Morton.

"Just a man," Frank replies.

"An ancient race," says Harmonica, his eyes turning to indicate the scene in front of them.

"Other Mortons'll come along and they'll kill it off."

"The future don't matter to us," says Frank. "Nothing matters now, not the land, not the money, not the woman."

Civilization has arrived, and Brett McBain knew the best way to help it take hold in the desert was to import someone like Jill from New Orleans, the closest place to the Old World on the American mainland. That she happens to have been a high class whore is an irony that Leone might have intended. It's certainly an interesting thought.

In a final scene before the showdown, Cheyenne and Jill talk about the future. Jill still doesn't know if hers will include Cheyenne or Harmonica, and you get the idea that she'd be happy with either, as long as it doesn't include Frank. Cheyenne tells her that whatever happens, it probably won't include Harmonica.

"People like that have something inside," he tells her. "Something to do with death."

I would go even further than that. Harmonica's theme – those three wheezing notes – are called "Judgment's theme" in the score, because the only point of Bronson's character is judgment, vengeance – and death. He was felled by Stony's bullet at the beginning of the film but rose up again, tending briefly to a wound that seems to have healed completely when we see him next. He introduces himself to Frank, over and over, with the names of dead men.

His skill as a gunman is unerring, even supernatural. No one survives him in a duel. Frank certainly doesn't, and with that his mission seems nearly complete. Cheyenne tells Jill that if Harmonica kills Frank, he'll come back, collect his things and leave; he also knows there's no place in Sweetwater for either of them, so Cheyenne – mortally wounded by a gut shot inflicted by the frightened Morton before he died – leaves with Harmonica, dying in a dusty gulch behind the homestead.

Having brought death with him – the death of Morton, of Frank and Cheyenne, of nearly every outlaw we meet – Harmonica rides out of town ahead of the railroad, Cheyenne's body draped across the saddle of his horse. It's The End, quite literally, of nearly everything in the film, including the West of the title, and I feel sorry for you if you don't have the patience to watch it till the end.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.