People still watched the evening news when Broadcast News was released in 1987. Cable news channels like CNN had been eating at viewership, but years before the internet or smart phones it was the most authoritative digest of important news stories day by day, and news anchors like Dan Rather, Peter Jennings and Tom Brokaw were still trusted and respected. For anyone born since the film was made, Broadcast News must look like a period film.

The top-rated show on network television in 1987, The Cosby Show on NBC, had a Nielsen rating of 27.8. The CBS Evening News with Rather – the most-watched of the network news shows at the time – had a rating of 12.4; the closest show to it on prime time that year (Jake and the Fatman, also on CBS) had a rating of 12.3. The big three networks had always run their news divisions as prestigious money losers, but after a round of corporate buy-outs and takeovers during the decade, the logic for subsidizing a perennial cash drain was being questioned.

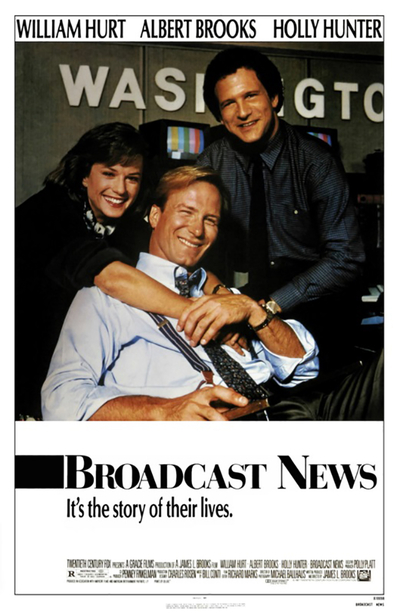

This is the setting into which we're introduced to the ménage a trois at the centre of James L. Brooks' film. After a comic prologue where the characters are introduced as adolescents in the early '60s, we meet TV news producer Jane (Holly Hunter) on her power walk, stopping to pick up the morning editions from a line of newspaper boxes outside the Nebraska hotel where she's staying while filming a story with Aaron (Albert Brooks) – a reporter at the Washington bureau of the network news division where she works, and her reluctant best friend.

(Newspaper boxes. They used to line the sidewalks at city intersections, outside bus and train stations along the corridors of the arrival and departure terminals at airports. There was a whole industry tasked with filling and servicing them. Give me a chance, kids, and I'll tell you all about pay phones, teletypes and stock tickers.)

While on the road, Jane is booked to give a speech at one of those conferences where TV and newspaper journalists, producers and editors used to gather several times a year to celebrate themselves, issue dire warnings, network for their next job, pad expense accounts and chip at the foundations of their marriages. It doesn't go well; she chooses to play Cassandra, scolding her audience and their employers for dumbing down the news with puff pieces and human interest in pursuit of better numbers.

Jane's delivery is dull and half-hearted, and nobody wants to be scolded for letting their standards slip if bumping a story about NATO and airing film of kids setting a record for dominos lets them keep their jobs for another year or two. The only exception is Tom (William Hurt), the anchor at a local affiliate who agrees with Jane while admitting that he – a good-looking man who's failed upward – embodies everything she detests about the human interest-centred news lite.

Ethical revulsion aside, Jane still clumsily attempts to seduce Tom while compulsively insulting him. A more desperate man might have weathered the scorn, but Tom is clearly able to pick and choose, and he leaves her room, but uses the house phone to tell her that he's been hired by her network, and will see her soon at the Washington bureau.

James L. Brooks was at the top of his field when he directed Broadcast News. His TV career hit its stride with Room 222 before he co-created The Mary Tyler Moore Show and its spin-off series Rhoda and Lou Grant. Since TV was still considered an inferior medium to the movies, he wrote and produced Alan J. Pakula's comedy Starting Over in 1979 before directing his first picture, Terms of Endearment, which won him an Oscar for writing, directing and best picture.

Brooks was uniquely suited to making TV shows and movies set in newsrooms since he'd begun his career in the CBS news department, starting as an usher before getting promoted to writer. (Back in the day when the idea of a journalism degree as a useful credential was considered unnecessary and even laughable.) He admitted later that he might have spent the rest of his career in journalism if he hadn't decided to move to Los Angeles in 1965 to take a job working on documentaries for producer David L. Wolper (Four Days in November, The Hellstrom Chronicle, Roots, The Thorn Birds). It was an unlucky move, since Brooks was laid off six months after arriving in L.A., but he bounced back, getting a job as a writer on My Mother the Car.

But while Brooks had a background in TV news, he didn't know much about being a woman in TV news in the '80s, so he brought in Susan Zirinsky, a CBS News producer, to consult on the script and production of Broadcast News. Zirinsky ended up being the model for Hunter's Jane; her voice can be heard off-screen in some scenes, and it's her handwriting on the pieces of tape that mark the buttons on Jane's switching board in the control room, during the scene where she has to feed Tom crucial information during a live report on a Libyan attack on a U.S. air base in Sicily.

Despite – or maybe because – the people making it had so much experience with and a stake in the state of television news, the movie is subtly but consistently excoriating about the ethical standards and probable future of the medium. Back in Washington, Aaron is having a water cooler conversation with his co-workers – the sort of bullshit-with-an-agenda chat where they test each other on questions like whether they'd tell a news source they loved them to get information, or if they'd televise executions. They all agree, without much apparent hesitation, to Aaron's wry dismay.

Tom arrives in Washington eager to learn, and as one of life's benighted but fortunate fools he is an empty vessel constantly needing to be filled. He also upends Jane's nonexistent love life – a sad affair that mostly involves gently fending off Aaron's occasional pleading, punctuated by crying jags, carefully scheduled not to impede her work.

There's no denying the attraction Jane and Tom feel for each other, just as Brooks does his best to make us understand how Tom, blithely and cheerfully, comes to violate Jane's ethics as a journalist. It's the major conflict in the film, but I wonder if a modern audience, born after it was made and unaware of Jane's ethical boundaries (which were, even then, becoming rarer in her profession), might watch the film and wonder to themselves "Really – that's it?"

After acquitting himself in his baptism of fire with the Libya story, Tom gets ambitious and produces a story on his own, about the then-new topic of date rape. It's not the sort of subject that serious news channels would have given airtime back then, but the finished piece resonates with the women watching it in the newsroom, including Jane, who gives Tom rare praise, despite having qualms with his decision to cut to him tearing up after his interview subject breaks down telling her story. Aaron, however, is not as moved, sarcastically praising Tom by saying "you really blew the lid off nookie."

Brooks' film is often praised for anticipating the coming decline of network news, which would be more severe than anyone imagined even in the late '80s. But this scene also pointed at other changes that were happening socially, where something that a roomful of professional women could relate to viscerally could be dismissed by a sophisticated, liberal man like Aaron as "nookie."

I often have to remind myself that Broadcast News – one of a handful of films (Goodfellas, Das Boot, The Maltese Falcon) that I have to keep watching when I catch them halfway through while flipping channels – is just as much a romantic comedy as it is a film about television news. This is mostly because that romance is so famously thwarted, by design, its ending pointedly lacking in the emotional payoff rom-com fans demand.

This is mostly because two of the three sides in the movie's romantic triangle aren't enhanced as much as they're defined by their quirks. Jane is highly competent, a workaholic who feels that one of her personal tragedies is being unerringly right about everything. Aaron is a sophisticated man – a prodigy who graduated high school early, speaks several languages and listens to wordy French pop music (Francis Cabrel's "L'Edition Speciale") to relax.

They're people whose insecurities and sense of superiority are constantly at work, often at the same time. One of the most famous lines from the film is Aaron, during one of his late night phone conversations with Jane, asking "Wouldn't this be a great world if insecurity and desperation made us attractive? If needy was a turn-on?"

Aaron is one of those men who's too smart to understand that they can't, and shouldn't, be virtues or turn-ons. And that no matter how hard they've tried to make them so it never works, because insecurity doesn't breed courage, desperation doesn't aid good decision making, and neediness inevitably elicits contempt. When I was a young man I might have sympathized with Aaron's lovelorn question, but thank God life disabused me of the notion.

It's what draws Jane to poor, dim, handsome Tom, the sort of man that men like Aaron hate on sight because, like the Devil, "he'll get all the great women." Tom might need a lot in the way of education, but he's never desperate, and only faintly insecure despite his obvious lack of skill as a real journalist, at least how Jane and Aaron would define it.

What Tom has that the blunt Jane and the contemptuous Aaron lacks is the emotional intelligence that helps him navigate his way into the new news, where feelings trump facts. When Jane discovers near the end of the film that Tom faked tears for the cutaway shot in his date rape piece, she reacts with a visceral sense of betrayal, more painful than if she discovered him with another woman. In her mind, it's a betrayal more profound than a personal one.

"You can get fired for things like that!" she tells him.

"I got promoted for things like that," he responds.

Off-screen for Brooks and his characters but not for the audience was one of the major factors threatening network news: CNN. My friend Verna Gates is a veteran journalist who was one of the original Atlanta crew for Ted Turner's experiment in 24-hour cable news programming, and she remembers the fledgling cable news station having to sue to get a place in the White House press corps.

The staff at CNN was young – average age 28 – and underpaid by comparison with network news staff and especially their star anchors and executives. Turner's non-union crew could be called off camera or out of editing bays to answer phones, and a satellite tech with a great voice could be given a job doing voiceovers. Verna remembers being Joan Cusack in the famous Broadcast News scene where the junior news producer rushes through the offices and hallways of the bureau to deliver a tape to the newsroom just in time to air.

The cable network aired stories from underserved markets outside the big cities, and provided breaking news coverage for big stories like the space shuttle explosion, the Mariel boatlift, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the first Gulf War – the kind of news that the networks would serve with a special bulletin like the Libya story in Broadcast News, before switching back to the sitcoms, soap operas, game shows and movies of the week that made them money.

Their paycheques might have bounced (once) but they had upward mobility at the station that the networks news operations only grudgingly offered, thanks to a steadily increasing market share. So they didn't have to worry about brutal and increasingly regular mass lay-offs, like the one that happens near the end of Broadcast News.

For most of the film Jane and Aaron are desperate to curry favour with the network's overpaid star anchor, played with comically hypertrophied gravitas by Jack Nicholson. He makes the trip to the Washington bureau in what he hopes will be seen as a show of solidarity on the day the lay-offs begin, but Brooks' camera shows him slinking away as soon as the first axe blow falls.

When one late middle-aged editor is seen exiting the office after being offered "early retirement," the network news president asks with emollient insincerity to let him know "if there's anything I can do for you."

"Well, I certainly hope you die soon," he responds affably. It's the line I wish I'd remembered when I was laid off from my newsroom job.

Jane's boss is laid off, but she gets his job. Aaron is spared the cuts – his abundant skills make him economical – but he quits on principle, taking a job at a small station in Portland. Tom says he was demoted, but when he reveals that his new posting is the London bureau, everyone tells him that this is actually a promotion, and that he's being groomed for the job of head anchor.

It's a tearful scene, and Jane says she feels the pain of it physically, in her bones. Tom admits that maybe he hasn't been there long enough, and in any case he's been through layoffs at every small station and affiliate he's worked at.

The layoffs force Tom and Jane to confront their feelings for each other – a test that Tom fails when Aaron tips off Jane to look at the raw footage from his date rape story. Earlier in the movie, after he admits to Jane that he loves her (how she missed it until then is baffling) after Jane attends the White House Correspondents Dinner with Tom, Aaron asks aloud "Does anyone ever win one of these things?"

In Broadcast News at least, the answer is no. The film apparently had a lot of fans who were so invested in the "Andie should have ended up with Duckie and not Blane" theorem that they've complained for years about the ending. In an epilogue set seven years after Jane left the airport without Tom, the trio are reunited again, at another one of those news journalism conferences.

Aaron is still in Portland, married and with a kid who looks just like him. Tom has failed his way to the job of head anchor, but he's aware enough of his inadequacies that he's turned down the editor-in-chief side of the job. Jane is the head of the Washington bureau, but she's decided to take the job that Tom has turned down, and will be working with him again in New York.

I don't feel at all cheated by the ending, since it was obvious to me – at least by the fifth or sixth time I watched it, many years after I first saw it in theatres – that there was no way Jane, Aaron or Tom would be happy with each other. Tom's betrayal of Jane's ethics – her only religion, as far as we can tell – was too egregious, and even Aaron might get tired of being emotionally grateful to Jane after the brief thrill of romantic success was achieved. And in any case I can't imagine that Tom and Jane won't have a brief but ultimately disappointing reprise in New York.

Even James L. Brooks admitted that the film was ultimately about "three people giving up on their last chance at real intimacy," even though he told a writer thirty years after the film premiered that it took him years to realize it.

What seems much worse is the inevitability that Tom – the fake crier, the journalist making himself part of the story – has ultimately triumphed by the end of the '80s, never mind in the decades to come, as network news viewership continues to plummet. Tom is too dumb to know he won – I don't think he ever thought there was a battle – but it's the sort of certain knowledge that will make Jane and Aaron increasingly bitter, even if they manage to retire with full pensions.

Mostly though it's hard to watch Broadcast News today without a sense of nostalgia. There's Bill Conti's soundtrack, for one – so mannered and polite, even jaunty, a perfect match for the '80s wardrobe - shoulder pads everywhere - and the houses and apartments full of tasteful, mismatched antiques and framed prints. Sure, television news might have been in trouble, but at least publishing was still healthy, and no matter how bad things got, there was no way they'd ever elect a president again with less gravitas than Gerald Ford.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.